No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

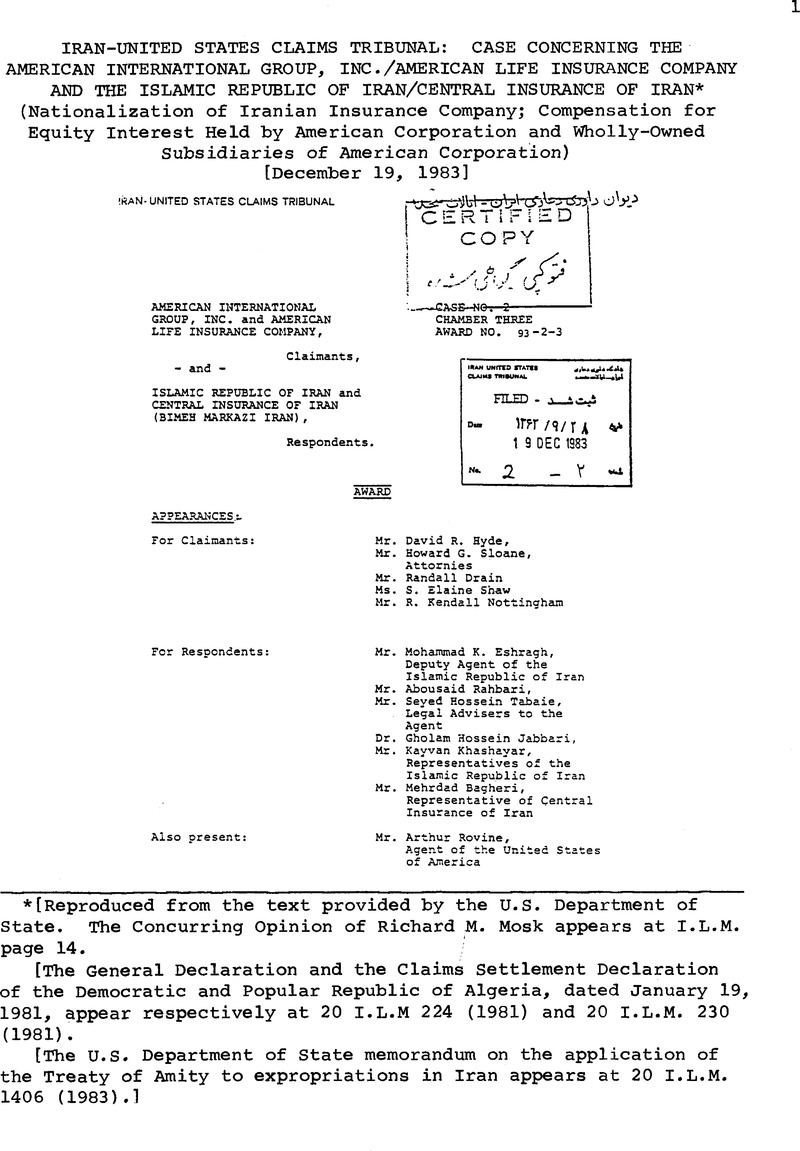

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Department of State. The Concurring Opinion of Richard M. Mosk appears at I.L.M. page 14.

[The General Declaration and the Claims Settlement Declaration of the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria, dated January 19, 1981, appear respectively at 20 I.L.M 224 (1981) and 20 I.L.M. 230 (1981).

[The U.S. Department of State memorandum on the application of the Treaty of Amity to expropriations in Iran appears at 20 I.L.M. 1406 (1983).]

page 2 note 1 In its Statement of Claim, AIG also claimed entitlement to unspecified amounts allegedly due under re-insurance contracts with Bimeh Markazi, but has not in subsequent pleadings or set forth the factual allegations upon which it based this claim or offered any evidence or argument on its behalf. The Tribunal deems this claim to have been withdrawn.

page 3 note 2 In its 20 September 1982 Memorial, the Claimant AIG alleges that certain actions which preceded that Law amounted in themselves to an expropriation of Iran America. However, Claimants do not state the date of this alleged expropriation; nor do they rely upon this contention in advancing their claim. Rather, Claimants continue to seek compensation from the date of the nationalization.

page 3 note 3 The Declaration of the Government of the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria dated 19 January 1981 (“General Declaration”) and the Declaration of the Government of the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria Concerning the Settlement of Claims by the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran dated 19 January 1981 (“Claims Settlement Declaration”).

page 6 note 4 American International Group,-Inc. et al. v. Islamic Republic of Iran and Central Insurance of Iran (Bimeh Markazi Iran), No. 79-3298 (D.D.C. 10 Jvily 19S0).

page 7 note 5 This and other currency conversions herein are based upon the official rate of exchange in effect on the date of nationalization, being 70.475 rials per US dollar.

page 7 note 6 The Respondents make no claim for this alleged indebtedness.

page 10 note 7 See ArSchaga, Jimenez de Recueil des Cours (1978 I ), p 286 and note 533: “The basic test is the certainty of the damage”Google Scholar.

page 10 note 8 See G. andreasson, Methods for Evaluation of Insurance Companies and Insurance Portfolios, 1980 (a paper submitted to and published by the International Congress of Actuaries), p 16: “In many markets, particularly the big ones, insurance companies' profits vary in a cyclical pattern ... To buy a company in a period just following a peak year can be very expensive, as there might follow only one or two-more acceptable years and-then a several years' period of loss ... The selection of time is very important as we have these cyclical patterns ...”

page 12 note * [See correction at I.L.M. page 13.]

page 14 note 1 Treaty of Amity, Economic Relations, and Consular Rights Between the United States of America and Iran, signed 15 August 1955, entered into force, 16 June 1957, T.I.A.S. No. 3853, 8 U.S.T. 900 (“Treaty of Amity”).

page 14 note 2 For a criticism of summary determinations of the value of nationalized property, see Lillich, “The Valuation of Nationalized Property by the Foreign Claims Settlement Commission”, in I The Valuation.of Nationalized Property in International Law 95, 97-99 (R.Lillich ed. 1972).

page 15 note 3 The effect of paragraph 5 of Article 65 of the Vienna Convention is unclear. A plea of termination in defense to a claim for breach of a treaty does not appear to constitute the instrument of notice required under Articles 65, paragraph 2, and 67, paragraph 2, of the Vienna Convention, to make the termination effective. Similarly, a fundamental change of circumstances, Art. 62 of the Vienna Convention, would seemingly not obviate notice requirements. In any case, Iran has not invoked, and under the circumstances cannot invoke, such a ground. See, e.g. , Article 62, paragraph 2(b), of the Vienna Convention. Moreover, Iran should be precluded by virtue of Article 45 of the Vienna Convention and general principles of estoppel from asserting that the Treaty was terminated. See infra at n.4.

page 15 note 4 See, e.g., Brief for Intervenor-Respondent The Islamic Republic of Iran 13, 29, 45, Dames & Moore v. Regan (U.S. Sup. Ct.) (Filed June, 1981); Memorandum of the Government of Iran in Opposition to Confirmation of Attachments 16-17, 74-75, Iranian Attachment Cases (S.D.N.Y.) (filed April 21, 1980) ; Memorandum of Davis Robinson, Legal Adviser of the U.S. Department of State, Application of the Treaty of Amity to Expropriations in Iran, 12? Cong. Rec. S -16055, n.6 (daily ed. Nov. 14, 1983). The United States Government continues to issue “treaty trader” and “treaty investor” visas to Iranian nationals pursuant to the Treaty of Amity. Id. at S 16058 n. 7.

page 16 note 5 The property protection provisions of the Treaty of Amity have not been superseded by the adoption of such United Nations resolutions as the United Nations Declaration on Permanent Sovereignty over National Resources, G.A. Res. 1803, 17 U.N. GACR Supp. (No. 17) at 15, U.N. Doc. A/5217 (1962), reprinted in 57 Am.J.Int'l L. 710(1963), or the 1974 United Nations Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States, G.A. Res. 3261, 29 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 31) at 50, U.N. Doc. A/9631 (1974), reprinted in 69 Am.J. Int'l L. 484 (1975) , as contended by Iran. If Iran wished to have Article IV, paragraph 2, of the Treaty of Amity amended in the light of those resolutions, it could have sought to negotiate such amendment; but it did not do so. Indeed, with respect to Resolution 3281, the Iranian delegate to the United Nations noted that approval thereof was “without prejudice to any arrangements or agreements reached between States concerning investments and modalities of compensation in the event of nationalization or expropriation of foreign property.” Legal Problems of Multinational Corporations 148 (K. Simmonds ed. 1977) (quoting U.N. Doc. A/C.2/SR. 1650, pp. 10-11).

page 16 note 6 Declaration of the Government of the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria Concerning the Settlement of Claims by the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran, dated 19 January 1981.

page 17 note 7 Claims Settlement Declaration and Declaration of the Government of the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria dated 19 January 1981(“General Declaration”).

page 17 note 8 See General Principle B of the General Declaration. A United States Court held in favor of Claimants against Iran on the basis of the Treaty of Amity. it should be noted that a claimant before the Tribunal does not have to exhaust local remedies and is not faced with such defenses as sovereign immunity and the act of state doctrine (see the Tribunal discussion of jurisdiction in this case).

page 18 note 9 Post World War II settlement practice has not modified international custom regarding promptness of compensation. Such settlements do not reflect legal determinations, but rather are negotiated resolutions of claims that obligations were breached. Each settlement agreement should be deemed sui generis. See Barcelona Traction Case, 1970 I.C.J. 3, 40 (Judgment of 5 February). Certainly the lengthy negotiation process leading to lump sum settlements has no. bearing on the appropriate time for the payment of compensation.

page 18 note 10 See also the negotiating history of the Treaty of Amity in Robinson Memorandum, 129 Cong. Rec. at S 16056-57.

page 19 note 11 Full compensation clearly contemplates effective compensation.

page 19 note 12 Various United Nations resolutions are not determinative of the customary international law standard. See discussion in Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Chase Manhattan Bank, 658 F.2d at 889-91; Amerasinghe, , “The Quantum of Compensation for Nationalized Property” in III The Valuation of Nationalized Property in International Law 91, 111-14 (R. Lillich ed. 1975)Google Scholar ; Texaco Overseas Petroleum Co. v. Libyan Arab Republic (Merits) 53 I.L.R. 422,484-95 (Dupuy, sole arb.)(Award of 19 January 1977); Higgins, “The Taking of Property by the State: Recent Developments in International Law,” 176 Rec. des Cours 259, 292-3 (1983); Schwebel, The Effect of Resolutions of the U ,N. General Assembly on Customary International Law 73 Am. Soc. Int'l L. Proc. 301 (1979) .

page 20 note 13 The value of lost prospective business has been recognized as compensable by international tribunals. R.N. Pomeroy et al. and Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Award No. 50-40-3 (8 June 1983); Chorz6w Factory Case (Merits) (Ger. v. Pol.), 1928 P.C.I.J., ser. A, No. 17 (Judgment of 13 September); Shufeldt Claim (U.S. v. Guat.), 2 R. Int'l Arb. Awards 1079, 1099 (1930); Lena Goldfields Arbitration (1930), reprinted in 36 Corn. L.Q. 42 (1950); Lighthouses Arbitration, Claim No. 27 (Fr. v. Gr.), 23 I.L.R. 299 (1956). The United States Foreign Claims Settlement Commission has valued business enterprises as going concerns. See Lillich, “The Valuation of Nationalized Property by the Foreign Claims Settlement Commission” in I The Valuation of Nationalized Property in International Law 95, 113-16 (R. Lillich, ed. 1972).

page 20 note 14 See ITT Industries, Inc. and The Islamic RepubJjc of Iran, Award No. 47-156-2 (Concurring Opinion of George 57 Aldrich)(26 May 1983); Restatement (Second) of Foreign Relations Law of the United States S188, comment b, at 565 (1965); Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development , Draft Convention on the Protection of Foreign Property, Art. 3, comment 9(a) at 27 (1967), reprinted in 7 I.L.M. 126 (1968); Draft Convention on the International Responsibility of States for Injuries to Aliens, Art. 10, paragraph 2 (b) , reprinted in 55 Am.J. Int'l L. 548, 553 (1961) ; Lillich, supra, at n. 13 p. 97; Lighthouses Arbitration, Claim No. 27 (Fr. v. Gr.), 23 I.L.R. 299, 301(1956) .