Article contents

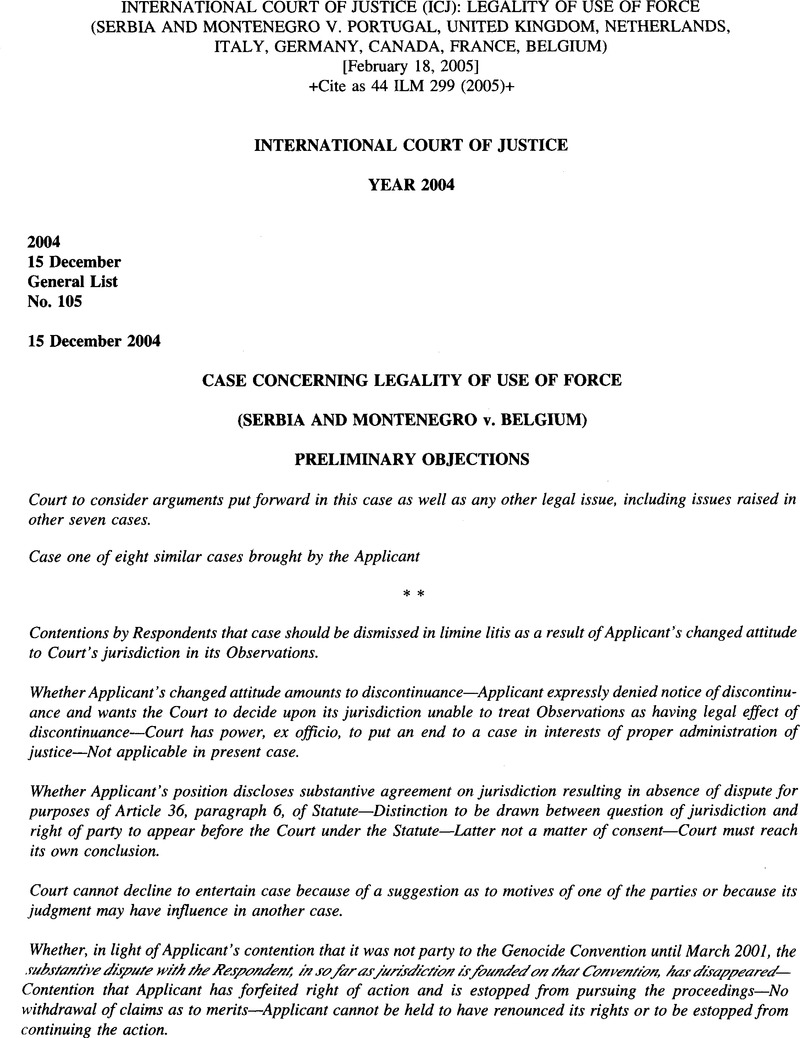

International Court of Justice (ICJ): Legality of Use of Force (Serbia and Montenegro v. Portugal, United Kingdom, Netherlands, Italy, Germany, Canada, France, Belgium)*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 2005

Footnotes

This document was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the ASIL's website (visited February 18, 2004)<http://www.asil.org.ilm/Ukraine.pdf>

References

Endnotes

1 Legality of Use of Force (Serbia and Montenegro v. Belgium), Preliminary Objections, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2004, para. 128.

2 Fisheries Jurisdiction (Spain v. Canada), Jurisdiction of the Court, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1998, p. 456, paras. 55-56.

3 On 4 February 2003, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia officially changed its name to “Serbia and Montenegro” (FRY-SM).

4 Declaration of the Joint Session of the SFRY, Republic of Serbia and Republic of Montenegro Assemblies, 27 April 1992, United Nations doc. S/23877, Annex, p. 2.

5 United Nations doc. A/46/915, Ann. I, p. 2.

6 United Nations docs. S/Res/777 and A/Res/47/1.

7 United Nations doc. S/Res/757.

8 United Nations doc. A/47/485, Ann.

9 In a series of resolutions, the General Assembly fixed a new rate of assessment for “Yugoslavia” of 0.11, 0.1025 and 0.10 per cent for the years 1995, 1996 and 1997 respectively (United Nations doc. A/Res/49/19B) and 0.060, 0.034 and 0.026 per cent for the years 1998, 1999, and 2000 respectively (United Nations doc. A/Res/52/215A).

10 Article 6 shall be interpreted in accordance with Annexes A and B.

11 For greater certainty, a condition for the receipt or continued receipt of an advantage referred to in paragraph 2 does not constitute a “commitment or undertaking” for the purposes of paragraph 1.

12 The Parties recognize that a patent does not necessarily confer market power.

13 For the United States, “laws” for purposes of this Article means an act of the United States Congress or regulations promulgated pursuant to an act of the United States Congress that is enforceable by action of the central level of government.

14 For the United States, ‘ ‘statutes or regulations'’ for purposes of this Article means an act of the United States Congress or regulations promulgated pursuant to an act of the United States Congress that is enforceable by action of the central level of government.

15 It is understood that the term “prudential reasons” includes the maintenance of the safety, soundness, integrity, or financial responsibility of individual financial institutions.

16 For greater certainty, measures of general application taken in pursuit of monetary and related credit policies or exchange rate policies do not include measures that expressly nullify or amend contractual provisions that specify the currency of denomination or the rate of exchange of currencies.

17 It is understood that the term “monetary authority of a Party” includes the finance ministry of a Party, or its equivalent, where that ministry has responsibilities with respect to monetary and related credit or exchange rate policies.

18 For purposes of this Article, “competent financial authorities” means, for the United States, the Department of the Treasury for banking and other financial services, and the Office of the United States Trade Representative, in coordination with the Department of Commerce and other agencies, for insurance; and for Uruguay, the Ministerio de Economía y Finanzasjn coordination with the Banco Central del Uruguay.

19 For the purposes of this Article, the “competent tax authorities” means: for the United States, the Assistant Secretary of the Treasury (Tax Policy), Department of the Treasury; and for Uruguay, the Director, Direccό in General Impositiva del Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas.

20 The “law of the respondent” means the law that a domestic court or tribunal of proper jurisdiction would apply in the same case

1 Legality of Use of Force (Serbia and Montenegro v. Belgium), Preliminary Objections, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2004, para. 128.

2 Fisheries Jurisdiction (Spain v. Canada), Jurisdiction of the Court, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1998, p. 456, paras. 55-56.

3 On 4 February 2003, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia officially changed its name to “Serbia and Montenegro” (Fry-SM).

4 Declaration of the Joint Session of the S Fry, Republic of Serbia and Republic of Montenegro Assemblies, 27 April 1992, United Nations doc. S/23877, Annex, p. 2.

5 United Nations doc. A/46/915, Ann. I, p. 2.

6 United Nations docs. S/Res/777 and A/Res/47/1.

7 United Nations doc. S/Res/757.

8 United Nations doc. A/47/485, Ann.

9 In a series of resolutions, the General Assembly fixed a new rate of assessment for “Yugoslavia” of 0.11, 0.1025 and 0.10 per cent for the years 1995, 1996 and 1997 respectively (United Nations doc. A/Res/49/19B) and 0.060, 0.034 and 0.026 per cent for the years 1998, 1999, and 2000 respectively (United Nations doc. A/Res/52/215A).

10 Application for Revision of the Judgment of 11 July 1996 in the Case concerning Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Yugoslavia), Preliminary Objections (Yugoslavia v. Bosnia and Herzegovina), I.C.J. Reports 2003, p. 23, para. 70.

11 Prosecutor v. Milan Milutinovic, Case No. IT-99-37-PT, Decision on Motion Challenging Jurisdiction, 6 May 2003, paras. 37-38, appeal dismissed, Case No. IT-99-37-AR72.2, Decision of 12 May 2004 (internal citations omitted).

12 Ibid, para. 39.

13 On 27 October 2000, the President of the Fry addressed a letter to the Secretary-General requesting admission of the Fry to membership, stating that “[i]n the wake of fundamental democratic changes that took place in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, in the capacity of President, I have the honour to request the admission of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia to membership in the United Nations in light of the implementation of Security Council resolution 777 (1992).” (United Nations doc. A/55/528-S/ 2000/1043, Ann.) As a result, on 1 November 2000, the General Assembly adopted resolution 55/12, stating that “Waving received the recommendation of the Security Council of 31 October 2000 that the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia should be admitted to membership in the United Nations'’ and ‘’ [h]aving considered the application for membership of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia'', it “[d]ecides to admit the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia to membership in the United Nations.“

14 Application for Revision of the Judgment of 11 July 1996 in the Case concerning Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Yugoslavia), Preliminary Objections (Yugoslavia v. Bosnia and Herzegovina), I.C.J. Reports 2003, p. 23, para. 71 (emphasis added).

15 Prosecutor v. Milan Milutinovic, Case No. IT-99-37-PT, Decision on Motion Challenging Jurisdiction, 6 May 2003, para. 44, appeal dismissed, Case No. IT-99-37-AR72.2, Decision of 12 May 2004.

16 Legality of Use of Force (Serbia and Montenegro v. Belgium), Preliminary Objections, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2004, para. 78.

17 ibid.

18 Although the Court is free to decide the issues submitted to it by the Parties for reasons other than those advanced by the Parties, it is undesirable as a matter of judicial policy for the Court to raise proprio motu a legal argument that is not determinative of one of the Applicant's submissions, unless there are ‘ ‘compelling considerations of international justice and of development of international law which favour a full measure of exhaustiveness” on the matter. Compare Oil Platforms (Islamic Republic of Iran v. United States of America), I.C.J. Reports 2003, separate opinion of Judge Higgins, para. 27 (“it is unlikely to be ‘desirable’ to deal with important and difficult matters, which are gratuitous to the determination of a point of law put by the Applicant in its submissions'’) with Lauterpacht, The Development of International Law by the International Court (1982), p. 37.

19 Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Provisional Measures, Order of 8 April 1993, I.C.J. Reports 1993, p. 14, para. 19 (emphasis added). See also League of Nations, The Records of the First Assembly, Meetings of the Committees, Third Committee, Annex 7, Report Submitted to the Third Committee by M. Hagerup on behalf of the Sub-Committee, p. 532 (“The access of other [non-members of the League of Nations] States to the Court will depend either on the special provisions of the Treaties in force (for example the provisions of the Treaties of Peace concerning the rights of minorities, labour, etc.) or else on a resolution of the Council“) (emphasis added).

20 Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Provisional Measures, Order of 8 April 1993, I.C.J. Reports 1993, p. 14, para. 19.

21 Legality of Use of Force (Serbia and Montenegro v. Belgium), Preliminary Objections, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2004, para. 101 (internal citations omitted).

22 The Court's interpretation conflicts with the prior jurisprudence of the Permanent Court in the Certain German Interests in Polish Upper Silesia case, in which the Permanent Court impliedly construed the expression “treaties in force” as meaning any treaty in force at the time when the case was brought before the Court. P.C.I.J., Series A, No. 6. See also statement of Registrar Ake Hammarskjöld: “The Council's Resolution of May 17th, 1922, would have no bearing on cases submitted to the Court under a general treaty; for any State which was a party to a general treaty might then, without making any special declaration [as required by the Security Council resolution], be a party before the Court. The only case, therefore, in which the Council's resolution applied was that in which a suit was brought before the Court by special agreement.” (1926 P.C.I.J., Series D, No. 2, Add., Revision of the Rules of the Court, p. 76.)

23 League of Nations, Records of the First Assembly, Plenary Meetings, Twentieth Plenary Meeting, Annex A, Reports on the Permanent Court of [International] Justice Presented by the Third Committee to the Assembly (1920), p. 463.

24 Secretariat of the League of Nations, Memorandum on the Different Questions Arising in Connection with the Establishment of the Permanent Court of International Justice, reprinted in PCIJ Advisory Committee of Jurists, Documents Presented to the Committee Relating to Existing Plans for the Establishment of a Permanent Court of International Justice (1920), p. 17.

25 1926 P.C.I.J., Series D, No. 2, Add., Acts and Documents, p. 106 (emphasis added).

26 Report of the Registrar of the Court, reprinted in 1936 P.C.I. J., Series D, No. 2, 3rd Add., p. 818 (“It was decided … not to lay down, once and for all, in what cases declarations were required (question of the Peace Treaties)“).

27 See M. Hudson, The Permanent Court of International Justice 1920-1942 (1972), pp. 439-444 (giving examples).

28 United Nations doc. A/96(I) (11 December 1946).

29 United Nations, Official Records of the General Assembly, Committees, Third Session, Part I, Sept.-Dec. 1948 Vol. 4, Report of the Economic and Social Council, Sixth Committee, Legal Questions, Sixty-first Meeting (1948), p. 5.

30 Secretariat of the League of Nations, Memorandum on the Different Questions Arising in Connection with the Establishment of the Permanent Court of International Justice, reprinted in PCIJ Advisory Committee of Jurists, Documents Presented to the Committee Relating to Existing Plans for the Establishment of a Permanent Court of International Justice (1920), p. 17.

31 P.C.I.J., Series A, No. 6.

32 Minutes of Meeting of the PCIJ on 21 July 1926 on amending its Rules of Court, at 1926 P.C.I.J., Series D, No. 2, Add., Acts and Documents, p. 105 (emphasis added).

33 The Court notes in para. 113 that, in the context of the present Court, there were no such treaties in force prior to the Statute.

34 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, Art. 53. See also Ian Brownlie, Principles of Public International Law (4th edn., 1990), pp. 512-515.

35 Yee, S., The Interpretation of “Treaties in Force” in Article 35 (2) of the Statute of the ICJ, 47 ICLQ 884, 903 Google Scholar

36 Reservations to the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Advisory Opinion, I.C.J. Reports 1951, p. 24.

37 Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Counter Claims, Order of 17 December 1997, I.C.J. Reports 1997, p. 258, para. 35.

38 The Fry argued in relation to all eight Respondents that the Court had jurisdiction ratione personae under the Genocide Convention. Because I find that the Court did not have jurisdiction ratione materiae, I will not proceed to consider the alternative grounds raised by the Fry in relation to particular respondent parties.

39 United Nations doc. ST/LEG/8. The passage was later “deleted by the Secretariat in response to the objections raised by a number of States that the text was contrary to the relevant Security Council and General Assembly resolutions and the pertinent opinions of the Arbitration Commission of the International Conference for Peace in Yugoslavia.” Legality of Use of Force (Serbia and Montenegro v. Belgium), Preliminary Objections, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2004, para. 71, citing United Nations docs. A/50/910- S/1996/231, A/51/95-S/1996/251, A/50/928-S/1996/263 and A/50/930-S/1996/260.

40 United Nations doc. A/46/915, Ann. I, p. 2.

41 Vienna Convention on Succession of States in respect of Treaties, Article 34, paragraph 1.

42 Schachter, O., “State Succession: The Once and Future Law”, 33 Va. J. Int'l Law (1992-1993), p. 257.Google Scholar

43 Gabcíkovo-Nagymaros Project (Hungary/Slovakia), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports, p. 62, para. 99. See also Digest of United States Practice in International Law (1980) 1041 n. 43 (U.S. State Department Legal Adviser expressing opinion that the rules of the Vienna Convention on Succession of States in respect of Treaties were “generally regarded as declarative of existing customary law”.

44 Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Yugoslavia v. Bosnia and Herzegovina), Preliminary Objections, I.C.J. Reports 1996 (II), separate opinion of Judge Weeramantry, pp. 645, 654; see also separate opinion of Judge Shahabuddeen, pp. 634-637 (recognizing that allowing a suspension of the operation of the Genocide Convention would be incompatible with the object and purpose of the treaty, and others which, like it, exist to safeguard the fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual and endorse the most elementary principles of morality).

45 Application for Revision of the Judgment of 11 July 1996 in the Case concerning Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Yugoslavia), Preliminary Objections (Yugoslavia v. Bosnia and Herzegovina), I.C.J. Reports 2003, pp. 16-17, para. 51 (citing Application of Yugoslavia, Ann. 27) (emphasis added).

46 Application for Revision of the Judgment of 11 July 1996 in the Case concerning Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Yugoslavia), Preliminary Objections (Yugoslavia v. Bosnia and Herzegovina), I.C.J. Reports 2003, p. 23, para. 71.

47 Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Preliminary Objections, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1996 (II), p. 612, para. 23.

48 Ibid., pp. 617, 621, paras. 34 and 41.

49 Ibid., p. 612, para. 24 (emphasis added).

50 Oil Platforms (Islamic Republic of Iran v. United States of America), Preliminary Objection, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1996, p. 803.

51 Legality of Use of Force (Serbia and Montenegro v. Belgium), Preliminary Objections, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2004, para. 79.

52 Ibid, para. 129.

1 Even in the jurisprudence of the Court the expression is sometimes used as a descriptive one. Exempli causa, in the case concerning Barcelona Traction, Light and Power Company, Limited, the Court used it to denote right of ‘ ‘a government to protect the interests of shareholders as such'’ which was in effect the matter of legal interest independent of the right of Belgium to appear before the Court (Preliminary Objections, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1964, p. 45). On the contrary, in the South West Africa cases the Court has drawn a clear distinction between “standing before the Court itself, i.e., locus standi, and “standing in the … phase of… proceedings (South West Africa, Second Phase, I.C.J. Reports 1996, p. 18, para. 4).

2 As stated by the Court “under the system of the Statute the seising of the Court by means of an Application is not ipso facto open to all States parties to the Statute, it is only open to the extent defined in the applicable Declarations.” (Nottebohm, Preliminary- Objection, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1953, p. 122.) It should be noted also that the Court in the Legality of the Use of Force case found “[w]hereas the Court, under its Statute, does not automatically have jurisdiction over legal disputes between States parties to that Statute or between other States to whom access to the Court has been granted … whereas the Court can therefore exercise jurisdiction only between States parties to a dispute who not only have access to the Court but also have accepted the jurisdiction of the Court, either in general form or for the individual dispute concerned” (Provisional Measures, I.C.J. Reports 1999 (I), p. 132, para. 20; emphasis added).

3 In the Order of 30 June 1999 the Court noted Belgium requested “that the question of the jurisdiction of the Court and of the admissibility of the Application in this case should be separately determined before any proceedings on the merits” (Legality of Use of Force, I.C.J. Reports 1999 (II), p. 989). For, “the fact that the various provisions regulating the incidental jurisdiction are included in the Statute … serves to supply a general consensual basis, through a State's being a party to the Charter and Statute, which are always part of the title of jurisdiction and always confer rights and impose obligations on its parties in relation to the Court and it's activities. But if it is obvious that the Court lacks all jurisdiction to deal with the case on the merits, then it automatically follows that it will lack all incidental jurisdiction whatsoever.'’ ( Rosenne, Shabtai, The Law and Practice of the International Court 1920-1996, Vol. II, 1997, pp. 598–599 Google Scholar.

4 Better known than judicial presumptions, legal presumptions (praesumptio iuris) are widely applied in international law. International tribunals use to resort to proof by inferences of fact (presomption de fait) or circumstantial evidence (Corfu Channel, Merits. Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1949, p. 18). For legal presumption in the practice of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, see T. Buergenthal, R. Norris, D. Shelton, Protecting Human Rights in the Americas, Selected Problems, 2nd ed., 1986, pp. 130-132 and pp. 139-144. The practice of international courts abounds in presumptions based on general principles of international law, whether positive as presumption of good faith (exempli causa, Mavrommatis Jerusalem Concessions, Judgment No. 5, 1925, P.C.I.J., Series A, No. 5, p. 43) or negative as presumption of abuse of right (Certain German Interests in Polish Upper Silesia, Merits, Judgment No. 7, 1926, P.C.I.J., Series A, No. 7, p. 30; Free Zones of Upper Savoy and the District of Gex, Second Phase, 1930, P.C.I.J. Series A, No. 24, p. 12; Corfu Channel, Merits, Judgment, 1949, I.C.J. Reports 1949, p. 4 at p. 119: dissenting opinion of Judge Ecer). The special weight they possess in the interpretation of treaties since the function of interpretation of treaties is to discover ‘ ‘what was, or what may reasonably be presumed to have been, the intention of the parties to a treaty when they concluded it'’ (Harvard Law School, Research in International Law, Part III, Law of Treaties, Art. 19, p. 940; emphasis added).

5 The letter of the Under-Secretary-General and Legal Counsel of the United Nations of 8 December 2000 relating to one of the relevant legal consequences of the admission of the Fry in the United Nations in the capacity of a successor State, is basically of the administrative nature. In that regard, it should be stressed that in its 1996 judgment dealing with the question of Bosnia and Herzegovina's participation in the Genocide Convention, the Court noted that “Bosnia and Herzegovina became a Member of the United Nations following the decisions adopted on 22 May 1992 by the Security Council and the General Assembly, bodies competent under the Charter. Article XI of the Genocide Convention opens it to ‘any Member of the United Nations'; from the time of its admission to the Organization, Bosnia and Herzegovina could thus become a party to the Convention.'’ ( Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Yugoslavia), Preliminary Objections, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1996 (II), p. 611, para. 19; emphasis added.)

6 Article 18 of the Charter enumerates, inter alia, “the admission of new Members to the United Nations.“

7 Cases concerning Factory at Chorzόw, Order of 25 May 1929, P.C.I. J., Series A, No. 19, p. 13; Delimitation of the Territorial Waters between the Island of Castellorizo and the Coasts of Anatolia, Order of 26 January 1933, P.C.I. J., Series A/B, No. 51, p. 6; Losinger, Order of 14 December 1936, P.C.I.J., Series A/B, No. 69, p. 101; Borchgrave, Order of 30 April 1938, P.C.I.J., Series A/B, No. 73, p. 5; Appeals from Certain Judgments of the Hungaro/Czechoslovak Mixed Arbitral Tribunal, Order of 12 May 1933, P.C.I.J., Series A/B, No. 56, p. 164; Legal Status of the South-Eastern Territory of Greenland, Order of 11 May 1933, P.C.I.J., Series A/B, No. 55, p. 159 (in this case the Court took note that Norway and Denmark had withdrawn their respective applications); Prince von Pless Administration, Order of 2 December 1933, P.C.I.J., Series A/B, No. 59, pp. 195-196; Polish Agrarian Reform and German Minority, Order of 2 December 1933, P.C.I.J., Series A/B, No. 60, pp. 202-203; Aerial Incident of 27 July 1955 (United States of America v. Bulgaria), Order of 30 May 1960, I.C.J. Reports 1960, pp. 146-148; Barcelona Traction, Light and Power Company, Limited, Order of 10 April 1961, I.C.J Reports 1961, pp. 9-10; Trial of Pakistani Prisoners of War, Order of 15 December 1973, I.C.J. Reports 1973, pp. 347-348; Border and Trans border Armed Actions (Nicaragua v. Costa Rica), Order of 19 August 1987, I.C.J. Reports 1987, pp. 182-183; Passage through the Great Belt (Finland v. Denmark), Order of 10 September 1992, I.C.J. Reports 1992, pp. 348-349; Vienna Convention on Consular Rights (Paraguay v. United States of America), Order of 10 November 1998, I.C.J. Reports 1998, p. 427. The acquiescence of respondent States has been presumed in the case concerning Protection of French Nationals and Protected Persons in Egypt, Order of 29 March 1950, I.C.J. Reports 1950, p. 60. On the basis of a unilateral act of the applicant, discontinuance has been effectuated in the cases concerning Denunciation of the Treaty of 2 November 1865 between China and Belgium, Order of 25 May 1929, P.C.I.J., Series A, No. 18, p. 7; Trial of Pakistani Prisoners of War, Order of 15 December 1973, I.C.J. Reports 1973, p. 348.

8 “The existence of jurisdiction of the Court in a given case is … not a question of fact, but a question of law to be resolved in the light of the relevant facts.” (Border and Transborder Armed Actions (Nicaragua v. Honduras), Jurisdiction and Admissibility, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1988, p. 76, para. 16.) The question of the Court's jurisdiction is “necessarily an antecedent and independent one—an objective question of law—which cannot be governed by preclusive considerations capable of being so expressed as to tell against either Party—or both Parties.” (Appeal Relating to the Jurisdiction of the ICAO Council, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1972, p. 54, para. 16 (c).)

9 Thus, the Court found itself in the situation of having to make a choice between Scilla and Haribda—or to allow the “case” to figure on the General List as a pending case for an indefinite period of time or to resort to the removal of the “case” from the General List as was done in a number of cases: Treatment in Hungary of Aircraft and Crew of United States of America (United States of America v. Hungary), Order of 12 July 1954, I.C.J. Reports 1954, pp. 99-101, and (United States of America v. Union of Soviet Socialist Republics), Order of 12 July 1954, I.C.J. Reports 1954, pp. 103-105; Aerial Incident of 10 March 1953, Order of 14 March 1956, I.C.J. Reports 1956, pp. 6-8; Aerial Incident of 4 September 1954, Order of 9 December 1958, I.C.J. Reports 1958, pp. 158-161; Aerial Incident of 7 November 1954, Order of 7 October 1959, I.C.J. Reports 1959, p. 276-278; Antarctica (United Kingdom v. Argentina), Order of 16 March 1956, I.C.J. Reports 1956, pp. 12-14, and (United Kingdom v. Chile), Order of 16 March 1956, I.C.J. Reports 1956, pp. 15-17. In the light of Article 38, paragraph 5, what the Court might do proprio motu, in specific circumstances and before effective seisin, is to take the initiative in removing a case from the General List which, in fact, is done in accordance with Articles 88 or 89 of the Rules of Court. As a point of illustration, mention can be made of the case concerning Maritime Delimitation between Guinea-Bissau and Senegal, Order of 8 November 1995, I.C.J. Reports 1995, p. 423.

10 It might be mentioned in passing that the practice for the ‘ ‘removal clause'’ to be included at all into the dispositif of a judgment of the Court is open to question; not only because of the fact that, as a rule, a case which has been completed is removed automatically from the General List of pending cases, but also because of the nature of the judicial decision of the Court which concerns the parties to the dispute rather than a matter that, basically, concerns the internal functioning of the Court.

11 See Legality of Use of Force (Serbia and Montenegro v. Belgium), Order of 2 June 1999, I.C.J. Reports 1999 (I), p. 130, para. 12; Legality of Use of Force (Serbia and Montenegro v. Canada), Order of 2 June 1999, I.C.J. Reports 1999 (I), p. 265, para. 12; Legality of Use of Force (Serbia and Montenegro v. Italy), Order of 2 June 1999, I.C.J. Reports 1999 (I), p. 487, para. 12.

12 Exempli causa, in “les affaires de la Compétence en matière de pêscheries, la Cour n'a pas prononcé une telle jonction et a rendu deux séries d'arrêts distincts, tant sur la compétence que sur le fond. Mais ceci ne lé pas empêché de regarder le Royaume-Uni et l'Allemagne comme faisant ‘cause commune’ dans la première phase de la procédure” ( Guillaume, G., “La ‘cause commune’ devant la Cour internationale de Justice”, Liber Amicorum—Mohammed Bedjaoui, 1999, pp. 330, 334–335 Google Scholar).

- 3

- Cited by