Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

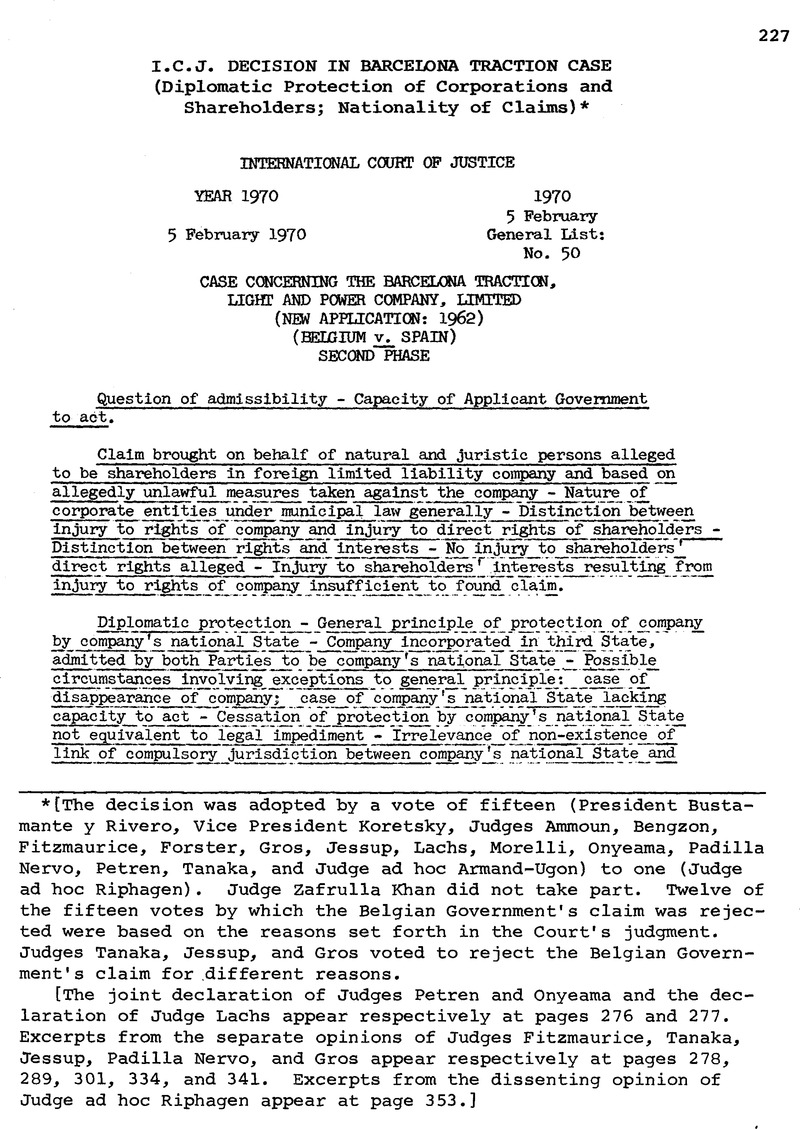

[The decision was adopted by a vote of fifteen (President Bustamante y Rivero , Vice P resident Koretsky, Judges Ammoun, Bengzon, Fitzmaurice , Forster , Gros, Jessup, Lachs, Morelli, Onyeama, Padilla Nervo, Petren , Tanaka, and Judge ad hoc Armand-Ugon) to one (Judge ad hoc Riphagen). Judge Zafrulla Khan did not take part . Twelve of the fifteen votes by which the Belgian Government’s claim was rejected were based on the reasons set forth in the Court’s judgment. Judges Tanaka, Jessup , and Gros voted t o reject the Belgian Government’s claim for different reasons.

[The joint declaration of Judges Petren and Onyeama and the declaration of Judge Lachs appear respectively at pages 276 and 277. Excerpts from the separate opinions of Judges Fitzmaurice , Tanaka, Jessup , Padilla Nervo, and Gros appear respectively at pages 278, 289, 301, 334, and 341. Excerpts from the dissenting opinion of Judge ad hoc Riphagen appear at page 353 .]

2 Although I now agree with my colleague Judge Morelli’s view that the question of Belgium’s right to claim on behalf of the Barcelona Traction Company’s shareholders, in so far as Belgian, is really a question of substance not of capacity (because the underlying issue is what rights do the shareholders themselves have), it is convenient for immediate purposes to treat the matter as one of Belgian Government standing.

20 Theoretically, the internal law of the country concerned might provide a means of recourse against the government in such circumstances: and political action might be possible. But in neither case would the essential point be affected.

21 I am not greatly impressed by the point which comes up in several connections that the Belgian position, with a big block of majority shareholding, is peculiar, and that in other cases there might be foreign shareholders of several nationalities and a consequent multiplicity of claims. This would only go to the quantum of reparation recoverable by the various governments, - and once the principle of claims on behalf of shareholders had been admitted for such circumstances, it would not be difficult to work out ways of avoiding a multiplicity of proceedings, which is what would really matter.

22 This is or has been the settled policy of a number of governments. I am not impressed by the argument that those who acquire shares in companies not of their own nationality must be deemed to know that this risk exists. That does not seem to me to affect the principle of the matter.

23 Or, like the nymph pursued by the ephebus, as depicted in the timeless stasis of the Attic vase that inspired the poet Keats’ celebrated Ode on a Grecian Urn (verse 2, lines 7–10):-

“Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal - yet, do not grieve;

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss,

Forever wilt thou love, and she be fair!”

54 The question whether there was jurisdiction under Spanish law, in the circumstances appertaining to the Barcelona .Company, is irrelevant or inconclusive for international purposes, since the very question at issue in international proceedings is whether the jurisdiction which a State confers upon its own courts, or otherwise assumes, is internationally valid.

55 Barcelona was a holding company, and a holding company is by definition not an operating company. This has been brought out in several decided cases, but is too often lost’ sight of.

56 Standing for “Ebro Irrigation and Power Co. Ltd.”

57 Standing for “Fuerzas Eléctricas de Cataluña, S.A.”

page 302 note 1 Thus, for example, where a corporation carries oh a purely commercial activity, international law does not “pierce the veil” to grant it the sovereign immunity attaching to the State by which it is wholly owned and managed; see Harvard Research in International Law, Report on Competence of Courts in Regard to Foreign States, 1932, Art. 12, p. 641.

page 302 note 1 Mr. Justice Marshall delivering the opinion of the Court in United States v. The Concentrated Phosphate Export Assn. Inc. et al., 89 S. Ct. p. 36l at pp. 366-367, 196b. Cf, the statement of a leading member of the New York Bar: “To give any degree of reality to the treatment, in legal terms, of the means for the settlement of international economic disputes, one must examine the international community, its emerging organizations, its dynamics, and relationships among its greatly expanded membership.” (Spofford, “Third Party Judgment and International Economic Transactions”, 113 Hague Recueil 1964, III, pp. 121-123.)

page 303 note 2 See Friedmann, et al., International Financial Aid 1966 Google Scholar; Kirdar, , The Structure of United Nations Economic Aid to Underdeveloped Countries, 1966 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

page 303 note 3 See Friedmann, , The Changing’ Structure of International Law 1964 Google Scholar, Chap. 14; Hyde, , “Economic Development Agreements”, 105 Hague Recueil 1962, I, p. 271 Google Scholar.

page 303 note 4 Blough, , “The Furtherance of Economic Development”, International Organization, 1965, Vo1 , XIX, p. 562 CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and especially, Dirk Strikker’s report to UNCTAD on “The Role of private enterprise in investment and promotion of exports in developing countries ”, (1968), UN Doc. TD/35/Rev.1, and “Panel on Foreign Investment in Developing Countries”, Amsterdam, 16-20 February, 1969, E/4654. ST/ECA/117.

page 304 note 1 The analogy may be drawn even though the nationality of shareholders is not the test of the nationality of a corporation for purposes of international law.

page 307 note 1 Belgian counsel’s argument on 30 June I969 about the “violation of Canadian sovereignty” and interference with the functions of the receiver as a Canadian “public authority” does not seem to reflect the actual thinking of the Canadian Government.

page 308 note 1 There is ample coverage of the literature in the excellent study by Ginther, op. cit., infra.

page 308 note 1 See the observations of the Permanent Court of International Justice on the control test in Certain German Interests in Polish Upper Silesia (Series A, No. 7, at p. 70).

page 309 note 2 Cf. Cahill, “Jurisdiction over Foreign Corporations and Individuals who Carry on Business within the Territory”,

page 309 note 30 Harvard Law Review, 1917, p. 676.

page 309 note 1 The wide range of unfavourable comments is reflected in the text and citations in Grossen, “Nationalité et Protection Diplomatique”, Ius et Lex, Festgabe zum 70 Geburtstag von Max Gutzwiller, 1959, p. 489. Brownlie, , Principles of Public International Law, 1966 Google Scholar, has a full treatment at pp. 323 ff. His position is generally favourable to the Court’s judgment.

page 309 note 2 Jessup, , “The United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea”, 59 Columbia Law Review, 1959, pp. 234, 256 Google Scholar. Meyers, , The Nationality of Ships, 1967 CrossRefGoogle Scholar, fully covers the question of flags of convenience, and the applicability of the rule to corporations is treated in Harris, “The Protection of Companies in International Law in the Light of the Nottebohm Case”, 18 International & Comparative Law Quarterly, April 1969, p. 275.

page 313 note 1 [Footnote omitted.]

page 313 note 1 “Legal fiction”, according to Morris Cohen, “is the mask that progress must wear to pass the faithful but blear-eyed watchers of our ancient legal treasures. But though legal fictions are useful in thus mitigating or absorbing the shock of innovation, they work havoc in the form of intellectual confusion”. Quoted in Transnational Law, p. 70.

page 321 note 1 Actually, in 1955 nine independent American companies were admitted to participate and each of the original American participating companies surrendered 1 per cent, of their shareholdings to the new group. For the purposes of this illustrative example, it is not necessary to explain further the. position of another British company, Iranian Oil Services Ltd. This account of the organization of the companies is based upon “History and Constitution of Iranian Oil Participants and Iranian Oil Services”, a talk by Mr. J. Addison, General Manager of Iranian Oil Participants Ltd. to Staff Information Meeting, Teheran, 21 August 1961.

page 321 note 1 See “The Oil Agreement Between Iran and the International Oil Consortium: The Law Controlling”, by Abolbashar Farmanfarma, of the Teheran Bar, in 34 Texas Law Review 259> 1955.

page 323 note 1 In its final submissions on 15 July 1969 under heading VI, Belgium asserted:

“that the Belgian Government has established that 88 per cent of Barcelona Traction’s capital was in Belgian-hands on the critical dates of 12 February 1948 and 14 June 1962 and so remained continuously between those dates ...” (Emphasis supplied.) The same assertion was amplified under heading V.

page 323 note 1 See Institut de droit international, Annuaire, I965, Vol. II, p. 270.

page 324 note 1 [Footnotes omitted.]

page 324 note 1 “... it is just possible that in talking the language of ‘ownership’ in relation to the flow of national capital, we are talking the language of history rather than the language of reality” ( Berle, , Power Without Property (Eng. ed. 1960), p. 45)Google Scholar.

This is true because, as Judge Tanaka has pointed out, anonymity brings about the separation of management from the ownership. (Cf. Morphologie des Groupes Financiers, Centre de Recherche et d’Information Socio-Politiques, 1962, pp. 9 and 60 and Meyssan, Les Droits des actionnaires et des autres Porteurs de Titres dans les Sociétés anonyms, 1962, pp. 9-10.)

page 328 note 1 The Belgian State in 1946 or 1947 possessed 10,000 shares of Sofina and 50,000 shares of Sidro. The shares were acquired in payment of a capital levy in 1946 but were apparently held by the State only briefly and probably not after 31 December 1947. See A.O.S., Ann. 30, App. 3, pp. 368 and 38l and Sub-App. 3, p. 388. It was in another context that Mr. Lauterpacht spoke, on 4 July 1969, of “the overall claim, here put forward by the Belgian Government, in respect of the injury done to the Belgian State by the unlawful acts for which Spain is responsible”.

page 330 note 1 [Footnote omitted.]

page 330 note 1 Securitas evidently was not a “passive trustee” in the sense described by Judge Augustus Hand in the San Antonio Land and Irrigation Co. case to which the Spanish side attached such importance.(New Documents, Vol. III, p. 114.)

page 330 note 1 Wigmore, Evidence, 3rd ed. 1940, Vol. 2, sees. 285 and 291. Wigmore traces the rule back to the beginning of the seventeenth century.

page 334 note 1 Likewise the Swedish company-law of 1944, revised in 1948, provides a right of action for a 10 per cent, minority of shareholders (Art. 129); there are similar provisions in Norwegian law (Art. 122 of the 1957 company-law) and in Articles 122-124 of the corresponding law of the Federal Republic of Germany.

page 336 note 1 The argument using the fact that Barcelona Traction shares have recently been transacted to prove that the company is still active is unconvincing. A few purchases or sales are enough to keep certain loan-stock, unpaid for over half a century, quoted on some exchanges. When it is said that the shareholder has the right to dispose of his share this certainly means to dispose of it under normal conditions, which - apart from a few speculations on the outcome of the present case before the Court - is no longer true in respect of Barcelona Traction.

page 348 note 1 Notwithstanding the references in the Judgment in paragraph 71 to various points of connection with Canada, I agree with the observations made by Judge Jessup in paragraph 49 of his separate opinion (in particular the footnote thereto). Those really in control of Barcelona Traction do not seem to have featured any genuine connection with Toronto.

page 350 note 1 There is nowhere to be found, in the laws of Spain in force at that time, any provisions concerning publication which are such that they enable the existence to be deduced of a general principle of law the infringement of which would ipso facto render the entire proceedings null and void. And if it be held that failure to publish the judgment at the bankrupt’s place of domicile constitutes a breach of Article 1044 (5) of the Spanish Commercial Code, then it is to the Spanish courts that complaint must first be addressed in this regard.

page 352 note 1 In several European legal systems a debtor can be declared bankrupt by the courts of a country in which he carries on a secondary occupation or possesses assets (Article 9 of the Italian, Article 2 of the Netherlands and Article 238 of the Federal German laws concerned), or even if his assets there are negative (French case-law). Some doubt is thrown on the character of Barcelona Traction as a holding company by direct activities in Spain (cf. hearing of 14 July 1969 [pp. 23f.]).