No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 May 2017

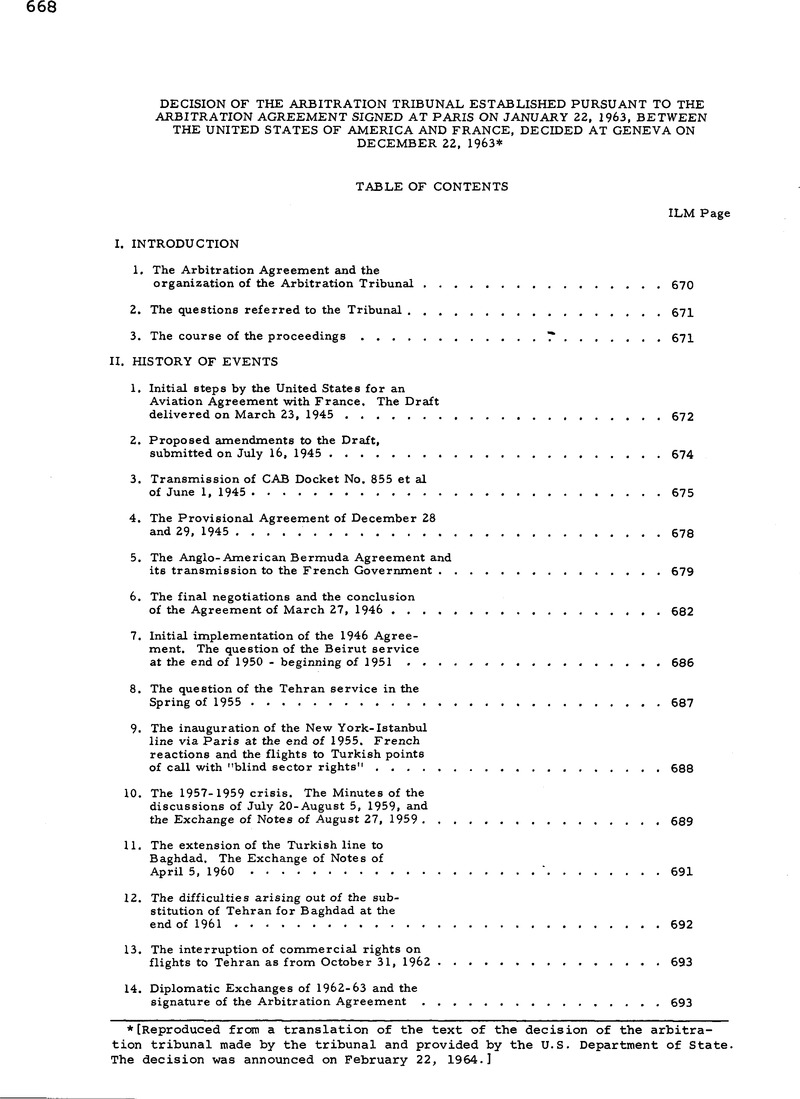

[Reproduced from a translation of the text of the decision of the arbitration tribunal made by the tribunal and provided by the U.S. Department of State. The decision was announced on February 22, 1964.]

1) In this connection, see FREDERICK, , Commercial Air Transportation, Fifth Ed., Homewood, 1961, p. 282: “Circumstances, therefore, forced the United States to adopt a policy of bilateralism. Between the years 1944 and 1954, bilateral air transport agreements have been entered into with 45 countries, based largely on what has come to be known as the “Bermuda Agreement” entered into between representatives of the United States and the United Kingdom at Bermuda in 1946.Google Scholar

* Notice will be given by the aeronautical authorities of the United States to the aeronautical authorities of the United Kingdom of the route service patterns according to which services will be inaugurated on these routes.

* Notice will be given by the aeronautical authorities of the United States to the aeronautical authorities of the United Kingdom of the route service patterns according to which services will be inaugurated on these routes.

1) By an exchange of notes dated Feb. 19 and Mar. 10, 1947, between the American Embassy at Paris and the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs it was agreed that the date of signature was omitted inadvertently and that this passage should read “Done at Paris , March 27, 1946.”

1) The French text of Section VII was as follows:

“Toute modification des lignes aériennes mentionn“es aux tableaux ci-annexés, qui affecterait le tracé de ces lignes sur des territoires d'Etat tiers autres que ceux des Parties Contractantes, ne sera pas considérée comme une modification à l'Annexe. Les autorités aéronautiques de chaque Partie Contractante pourront en conséquence procéder unilatéralement à une telle modification sous réserve toutefois de sa notification sans délai aux autorités aéronautiques de l'autre Partie Contractante.

Si ces dernières estiment, eu égard aux principes énoncés à la Section IV de la présente Annexe, que les intérêts de leurs entreprises nationales sont affectés par le fait qu'un trafic est assuré entre leur propre territoire et la nouvelle escale en pays tiers par les entreprises de l'autre pays, elles se concerteront avec les autorités aéronautiques de l'autre Partie Contractante afin de parvenir à un accord satisfaisant.”

* [French text of Decision reads “Bagdad” instead of Ankara.]

1) Publications of the P.C.I.J., Series B, Nos. 2 and 3, page 22. Further on in the same Opinion the Court confirmed the principle in the following terms: “ … the context is the final test, and in the present instance the Court must consider the position in which these words are found and the sense in which they are employed in Part XIII of the Treaty of Versailles.” (Ibid., page 35).

2) Publications of the P.C.I.J., Series B, No. 11, pp. 39 and 40. Judge Anzilotti has defined the principle in question in the same terms in his individual Opinion regarding the Case of the Customs Regime between Germany and Austria (Protocol of March 19, 1931), Publications of the P.C.I.J., Series A/B, No. 41, p. 60. The Institut de Droit International, in Article I of the Resolution on the Interpretation of Treaties adopted at Granada in 1956, asserted that: “the terms of the provisions of the treaty should be interpreted in the context as a whole”.

3) Publications of the P.C.I.J., Series A/B, No. 53, p. 52.

4) In the History of Events section above, we have seen that the terminology employed by the CAB defines the two as “general route” and “specific route”.

5) Publications of the P.C.I.J., Series A/B, No. 44, p. 33.

1) Publications of the P.C.I.J., Series A/B, No. 62, p. 13. Although it maintained “that there is no occasion to have regard to preparatory work if the text of a Convention is sufficiently clear in itself”, the Court also made an examination of the preparatory work, even in cases of this kind, both to make certain that this preparatory work “would not furnish anything calculated to overrule the construction indicated by the actual terms” of the text under consideration (Decision No. 7, of September 7, 1927, regarding the Case of the S. S. “Lotus”, Publications of the P.C.I.J., Series A, No. 10, p. 17), and “in order to see whether or not it confirmed … the conclusion reached on a study of the text of the Convention“; (Advisory Opinion of November 15, 1932, on Interpretation of the Convention of 1919 concerning employment of women during the night. Publications of the P.C.I. J., Series A/B, No. 50, pp. 378-380). In his dissenting opinion regarding the latter Opinion, Judge Anzilotti had stressed the need to “refer to the preparatory work … to verify the existence of an intention not necessarily emerging from the text but likewise not necessarily excluded by that text” (Ibid., p. 388).

The importance of preparatory work in the Decision of the International Court of Justice in the Case of the Aerial Incident of July 27, 1955, and in the work of the United Nations International Law Commission in connection with Treaty Law, has also been stressed (See ROSENNE, Travaux pre“paratoires, the “International &c Comparative Law Quarterly”, 1963, pp. 1378 et seq.).

Preparatory work has been used as a means of interpretation in numerous arbitration decisions. It is expressly mentioned in Article 19. Interpretation of Treaties of the “Draft Convention on the Law of Treaties” prepared for the codification of international law by Harvard Law School (“Supplement to the American Journal of International Law”, 29, 1935, pp. 937 et seq); and in Article 2 para. 2 of the Resolution of Granada of 1956 of the Institut de Droit International.

6) Precisely because of this, the route structure in the United States - United Kingdom Agreement is described by BIN CHENG as “semiflexible”: The Law of International Air Transport, London, 1962, p. 394.Google Scholar

7) Section IV of the Annex to the United States - United Kingdom Agreement is largely homologous to Section VII of the Annex to the United States- France Agreement, but it appears destined to play a more important role precisely because of the different technique employed in describing routes.

8) The International Court of Justice used the consideration of the “purpose” of a Convention as a criterion of interpretation, in its decision of November 28, 1958, regarding The case concerning the application of the Convention of 1902 governing the guardianship of infants (Netherlands v. Sweden), I.C.J. Report, 1958, pp. 68 & 69. Article 19 of the “Draft Convention” of Harvard Law School in point of fact begins with the assertion that “A treaty is to be interpreted in the light of the general purpose which it is intended to serve”. The “taking into consideration of the purpose of the treaty” also figures under c) of Article 2 of the Resolution of Granada of the Institut de Droit International.

9) The Permanent Court of International Justice, in its Decision No. 16 of September 10, 1929, concerning the Case relating to the Territorial Jurisdiction of the International Commission of the River Oder, (Publications of the P.C.I.J., Series A, No. 23, p. 26), while recommending the greatest prudence in this connection, admitted that “that interpretation should be adopted which is most favourable to the freedom of States”, in cases where “in spite of all pertinent considerations, the intention of the parties still remains doubtful”.

In the arbitration decision of July 18, 1932, in connection with the Case of the vessels “Kronprinz Gustaf Adolf” and “Pacific” between Sweden and the United States (United Nations Reports, Judgments, Advisory Opinions and Orders II, p. 1254), the Arbitrator Borel observed that “considering the natural state of liberty and independence which is inherent in soveriegn States, they are not to be presumed to have abandoned any part thereof, the consequence being that the high contracting Parties to a Treaty are to be considered as bound only within the limits of what can be clearly and unequivocally found in the provisions agreed to and that those provisions, in case of doubt, are to be interpreted in favour of the natural liberty and independence of the Party concerned”.

10) In the French text: “La description de la route telle qu'elle figurait dans le tableau des routes”.

11) Publications of the P.C.I.J., Series B, Nos. 2 and 3, p. 39.

12) Publications of the P.C.I.J., Series B, No. 15, p. 18:

“The intention of the Parties, which is to be ascertained from the contents of the Agreement, taking into consideration the manner in which the Agreement has been applied is decisive. This principle of interpretation should be applied by the Court in the present case.”

13) I. C. J., Report, 1962, pp. 32 and 33:

“Even if there were any doubt as to Siam's acceptance of the map in 1908, and hence of the frontier indicated thereon, the Court would consider, in the light of the subsequent course of events, that Thailand is now precluded by her conduct from asserting that she did not accept it. She has, for 50 years, enjoyed such benefits as the Treaty of 1904 conferred on her … France and through her Cambodia relied on Thailand’s acceptance of the map … The Court considers further that, looked at as a whole, Thailand’s subsequent conduct confirms and bears out her original acceptance …”.

The consideration of the “subsequent conduct of the parties in applying the provisions of a Treaty” is put forward as a means of interpretation in Article 19 of the “Draft Convention” of Harvard Law School. The “practice followed in the effective application of the Treaty” figures as a subsidiary legitimate means of interpretation in Article 2, para. 2b) of the Resolution of Granad a of the Institut de Droit International.

14) See FREDERICK, Commercial Air Transportation, cit. supra, p. 163:

“Ultimately the Board took action to develop competition on all routes, which, in its opinion, exhibited two carrier traffic potential …”.

15) It is worth recalling that on the map annexed to the CAB Decisions contained in Docket 855 et al., Beirut appeared as situated almost astride the demarcation line of the southern and central routes.

16) In its Decision of June 15, 1962, regarding the Case concerning the Temple of Préah Vihéar (Cambodia v. Thailand), the International Court of Justice seems to have taken into consideration the conduct of the Parties not only as a subsidiary means in case of doubt as to the interpretation to be given to the instrument under examination, but also as a possible source of a modification in the juridical situation, in the event that it had been sought to draw a different conclusion from the simple interpretation of the instrument in question. According to the Court, in fact:

“Both parties, by their conduct, recognized the line and therefore in effect agreed to regard it as being the frontier line.” (I.C.J., 1962, p. 33)

17) This identity of effects eliminates the practical consequences of the doctrinal divergence between the partisans of the theory according to which acquiescence is equivalent to tacit consent (e.g. FITZMAURICE, The Law and Procedure of the International Court of Justice, 1951-4: General Principles and Sources of Law, “British Yearbook of International Law”, XXX, 1953, pp. 27 et seq.; and even more clearly MacGIBBON, The Scope of Acquiescence in International Law, ibid., XXXI, 1954, pp. 143 et seq.; and Customary International Law and Acquiescence, ibid., XXXIII, 1957, p. 144 et seq.) and those for whom acquiescence, while it is a phenomenon that is equivalent in its effects to tacit consent, should in theory be distinguished from it (for example, SPERDUTI, Prescrizione, consuetudine et acquiescenza, “R “Rivista di diritto internazionale”, 1961, pp. 7 et seq.).

18) ANZILOTTI, Corso di diritto internazionale vol. I, introduzione - Teorie generali, 4th Edition, Padua, 1955, p. 292, had already observed that silence after regular notification of a fact, when the State could express its protests and reservations, can certainly be interpreted as an acceptance of the fact and an abandoning of conflicting claims that the said State could have put forward. The fact of not having raised objections at the time when they could have been raised, was considered to imply acquiescence in the Decision of December 18, 1951, of the International Court of Justice regarding the Fisheries Case (United Kingdom v. Norway) (I.C.J., Report, 1951, p. 139). In his comments on this Decision, FITZMAURICE, The Law and Procedure, op. cit., p. 33, merely drew attention to the fact that the absence of opposition does not necessarily of itself imply that there has been consent or acquiescence on the part of the State concerned, and that this should be judged from the circumstances.

The International Court of Justice subsequently largely applied this principle in its Decision of November 18, I960, regarding the Case concerning the Arbitral Award made by the King of Spain on December 23, 1906, (Honduras v. Nicaragua). The Court, in fact, concluded:

“ … that no objection was taken by Nicaragua to the jurisdiction of the King of Spain as Arbitrator, either on the ground …, or on the ground …, the Court considers that it is no longer open to Nicaragua to rely on either of these contentions as furnishing a ground for the nullity of the Award.” (I.C.J., Report, I960, p. 209);

and that:

“In the judgment of the Court, Nicaragua by express declaration and by conduct recognized the Award as valid and it is no longer open to Nicaragua to go back upon that recognition.” (I.C.J., Report, 1960, p. 213).

19) Referring to the written answer submitted by the United Kingdom in the Fisheries Case, Fitzmaurice, The Law and Procedure, cit. supra, p. 29, recalls that recourse to simple formal protest in cases where concrete measures could have been taken to put an end to the situation which is the subject of the protest, “can in the end be construed as a … tacit acquiescence in the situation”.