No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

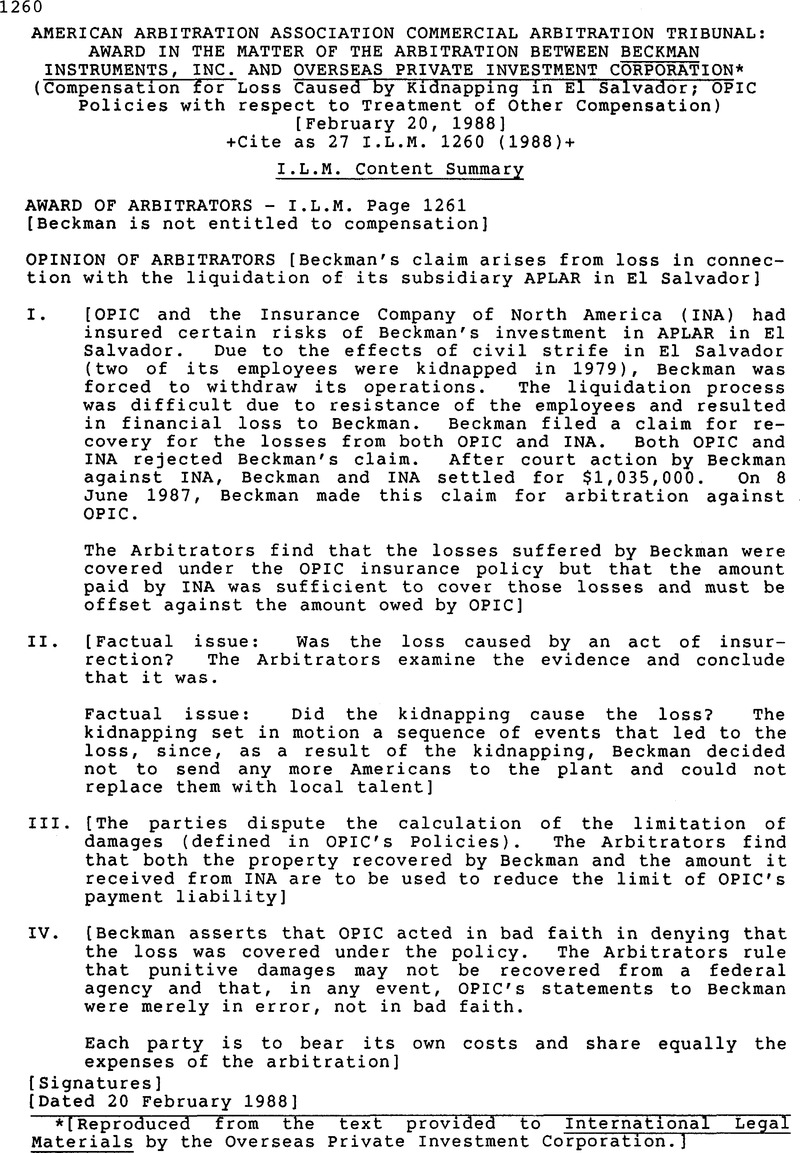

* [Reproduced from the text provided to International Legal Materials by the Overseas Private Investment Corporation.]

* As defined in the OPIC insurance contracts.

1 OPIC issued a Preliminary Memorandum of Determinations on October 31, 1980, and gave Beckman an opportunity to submit its views thereon for consideration in connection with the Final Determination. Beckman responded by making additional submissions to OPIC.

2 The term Covered Property means the tangible property owned by Aplar.

3 The OPIC Policies do not define the term “insurrection,” but the court in Pan American World Airways v. Aetna Casualty & Surety, 505 F.2d 989, 1005 (2d. Cir. 1974) found that it involves “an intent to overthrow a lawfully constituted government.” We accept this definition.

4 We note the report, introduced by OPIC, that Mr. Roeder was charged with kidnapping but acquitted by a court in El Salvador. While it may well be, as OPIC contends, that this decision should not be given undue credence, because of the highly politicized judicial system in El Salvador, it hardly gives us a basis for inferring that Roeder was responsible for the McDonald-Buchelli kidnapping. Even if we were to assume (and we have no basis for so doing) that Mr. Roeder was all that OPIC claims he was, we would still have no basis in the record for finding that he was involved in these kidnappings.

5 Mr. Steinmeyer was also Chairman of the "Special Events" (Crisis Control) Committee which made the major decisions concerning Aplar at this time.

6 To break the chain of causation, the intervening or interrupting cause must be one which is “not brought into operation by the original wrongful act, but operating entirely independent thereof, it must be such a cause as would have produced the result without the cooperation of the original wrong.” Grover Hill Grain Co. v. Baughman-Oster, Inc., 728 F.2d 784 (6th Cir. 1984) (applying Ohio law); Freeman v. United States, 509 F.2d 626 (6th Cir. 1975) (also applying Ohio law); Harper, James and Gray, 4 The Law of Torts S 20.5, at 149 (2d. ed. 1956).

7 The OPIC Policies define “Net Investment” as, “on any date, the sum of (i) the principal then outstanding and the interest then accrued and unpaid in connection with the Investment contributed by the Investor for debt Securities owned by the Investor on such date, and (ii) the amount of the Investment contributed by the Investor for equity Securities owned by the Investor on such date less the Return of Capital on such equity Securities, adjusted for the United States dollar equivalent … of such equity Securities’ ratable share of net retained earnings and losses … of the Foreign Enterprise occurring after the date of acquisition by the Investor of the Securities.” Section 1.24. Since Net Investment exceeds the Investor's Share of Damage (however defined), this figure is irrelevant to our decision.

8 The OPIC Policies define “Date of Damage” as “the first day on which occurs the Damage in question.” Section 1.09.

9 Mr. Dennis Wilson, formally the Comptroller of the Electro Products Group of Beckman, testified that he chose December 31, 1979 as the Date of Damage because Aplar, as a legal entity, engaged in no further product shipments after that date.

10 The formula to determine the Investor's Share is:Aplar's equity + Aplar's Long Term Debt x % Insured/Aplar's Equity + Aplar's Total Debt

11 Letter of January 27, 1988, at 4.

12 OPIC argues that Beckman recovered substantially more property, but the difference is not relevant to our decision.

13 The California statute makes it an unfair claims practice for an insurance company knowingly to fail "to provide promptly a reasonable explanation of the basis relied on in the insurance policy, in relation to the facts or applicable law, for the denial of a claim ..." California Insurance Code S 740.03(h)(13).

14 Beckman's General Counsel William H. May testified that INA did not want any allocation set out in the agreement.

15 See, Shernoff, Gage, and Levine, Insurance Bad Faith Litigation S 8.05, at 8-14-8-15 (1987); Harris v. Wagshal, 343 A.2d 283,289 (D.C. 1975); Finney v. Lockhart, 35 Cal. 2d 161,163-64, 217 P.2d 19 (1950).

16 This point disposes also of Beckman's alternative suggestion that we allocate the settlement as between actual and punitive damages. In any event, we have no basis for making such an allocation.

17 See Kirkland v. Ohio Casualty Insurance Co., 18 Wash. App. 538, 569 P.2d 1218, 1223 (1977); Insurance Co. of North America v. Nicholas, 533 S.W.2d 204, 206 (Ark. 1976); Continental Insurance Co. v. Commercial Union Insurance Co., 27 A.D. 2d 333,278 N.Y.S. 2d 995, 998 (1967); Reliance Insurance Co. v. St. Paul Surplus Lines Insurance Co., 753 F.2d 1288, 1290 (4th Cir.1985); and Washington v. Group Hospitalization, Inc., 585 F. Supp. 517, 520 (D.D.C. 1984).

18 Letter of January 27, 1988 from counsel.

19 Central Armature Works v. American Motorists Insurance Co., 520 F. Supp. 283, 292 (D.D.C. 1980).

20 Matter of Sparkman, 703 F.2d 1097, 1101 (9th Cir. 1983); Painter v. Tennessee Vallev Authority, 476 F.2d 943, 944 (5th Cir. 1973).

21 Commercial Arbitration Rules of the American Arbitration Association (Aim. July 1984), Rule SO.