No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 May 2017

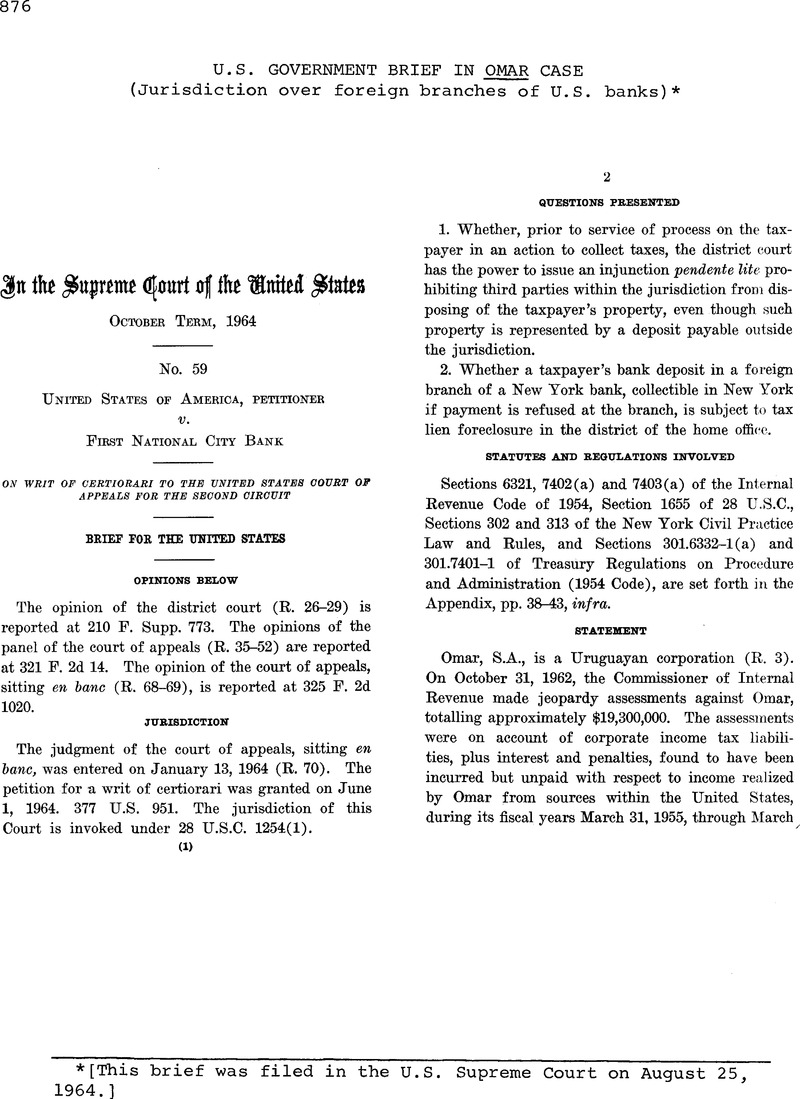

[This brief was filed in the U.S. Supreme Court on August 25, 1964.]

1 Omar failed to pay these assessments (E. 4-6). On May 20, 1963, Omar petitioned the Tax Court for a redetermination of these deficiencies. Docket No. 2041-63. No decision has been rendered in that proceeding. Since a jeopardy assessment is involved here, collection is authorized despite the pendency of Tax Court proceedings. See Section 6213(a), Internal Revenue Code of 1954.

2 The district court excluded First National City Trust Company and Belgian-American Bank & Trust Company from the injunction, on the basis of a satisfactory showing that neither they nor their branches or agents held any of Omar’s assets (R. 21-22, 25, 28-29). Kespondent, in opposing the motion for a preliminary injunction, filed an affidavit by one of its vice-presidents which affirmatively stated that Omar was not a depositor of the bank at its head office or any domestic branch, but neither affirmed nor denied that Omar was a depositor at any of the bank’s foreign branches (R. 23-24). The location and other details of Omar’s foreign branch accounts, if they exist, now await further clarification in the district court, pending disposition by this Court of this proceeding.

3 Judge Kaufman did not participate in the rehearing. Judge Clark died after argument but before announcement of the decision. It was noted that he had indicated his intention to vote for affirmance of the district court. An equal division would have resulted in affirmance. Farrand Optical Co. v. United States, 317 F. 2d 875, 885-886 (C.A. 2).

4 Although respondent’s brief in opposition indicates, on the basis of a letter from taxpayer’s counsel, that taxpayer’s only account is at Montevideo (Br. in Op., p. 5), the extent and whereabouts of deposits with respondent payable directly or beneficially to Omar is a proper subject of proof in the district court. Litigation of this fact question in a plenary proceeding has so far been precluded by respondent’s appeal from the temporary injunction.

5 Cf. Lamb, Group Banking, p. 46: “Deposits are received in all areas served by the branches and these combined liabilities become the debt of the parent institution.”

6 This order can be made effective without imposing sanctions for contempt. The district court, acting under Rule 70 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, could order a person appointed by the court to transfer the right to the deposits to the United States. The United States could then demand payment abroad, and, if payment were refused, could collect by suit in the United States. See Soboloff v. National City Bank, 130 Misc. 66, 224 N.Y.S. 102, affirmed, 223 App. Div. 754, 227 N.Y.S. 907, affirmed, 250 N.Y. 69, 164 N.E. 745; cf. Corbett v. Nutt, 10 Wall. 464; Watkins v. Holman, 16 Pet. 25; Roller v. Murray, 234 U.S. 738.

7 In United States v. Morris & Essex B. Co., 135 F. 2d 711 (C.A. 2), certiorari denied, 320 U.S. 754, a temporary injunction restraining payment by a delinquent taxpayer’s debtor to the taxpayer’s shareholders was sustained. The Second Circuit, per Judge Learned Hand, first determined that the shareholders and the taxpayer were to be considered one and the same. It then satisfied itself that if certain steps were taken by the government, the tax debt could be collected from the money owed by the taxpayer’s debtor. It concluded: “The path being therefore cleared for an action by the plaintiff as substitute obligee of the lessor’s [taxpayer’s] right of action against the lessee [debtor], the tax can be recovered in full, and to that end the asset must be preserved meanwhile.” 135 F. 2d at 713-714. (Emphasis added.)

8 The fact that the order affects the rights of the yet-absent defendant by “freezing” its deposits in Montevideo is no bar to relief. In Goldlawr, Inc. v. Heiman, 369 U.S. 463, this Court sustained the district court’s power to transfer an action to another district under 28 U.S.C. 1406(a) even though service over defendants could not be had in the transferor district. See United States v. Berkowitz, 328 F. 2d 358 (C.A. 3), certiorari pending, No. 125, 1964 Term; Koehring Co. v. Hyde Construction Co., 324 F. 2d 295 (C.A. 5) (transfer under 28 U.S.C. 1404(a) sustained notwithstanding absence of defendants). These instances obviously involved more serious effects upon the absent defendants than the “freezing” of funds in this case.

9 Section 302(a) did not become effective until September 1, 1963. However, as does its Illinois counterpart, the section applies to transactions occurring before its effective date. See, e.g., Steele v. DeLeeuw, 40 Misc. 2d 807, 244 N.Y.S. 2d 97; Patrick Ellam, Inc. v. Nieves, 41 Misc. 2d 186, 245 N.Y.S. 2d 545; William Band, Inc. v. Joy as DeFantasia, S.A., 41 Misc. 2d 838, 246 N.Y.S. 2d 778; United States v. Montreal Trust Co., supra. See also Nelson v. Miller, 11 Ill. 2d 378, 143 N.E. 2d 673. Although the district court’s order was issued before the statute became effective, there was still the possibility at that time that Omar might make a general or special appearance. In any event, since service on Omar may now be effected under Section 302(a), the district court’s order should be sustained so as to enable the government to utilize its presently available remedies.

10 There is a well recognized difference between considering a debt to be present within a jurisdiction for purposes of attachment or other quasi in rem proceedings and considering the debtor present for purposes of in personam orders. In Douglass v. Phenix Insurance Co., 138 N.Y. 209, 219, for example, the New York Court of Appeals held that a debt’s situs for attachment purposes was only at the domicile of the creditor or debtor, even though the debtor might obviously be served elsewhere. That decision was subsequently overruled by statute. See Morris Plan Ind. Bank v. Gunning, 295 N.Y. 324, 329-330. Under Harris v. Balk, 198 U.S. 215, it is, of course, permissible for a State to treat the debt as “following the debtor.” But that decision does not require a State to do so; nor does it compel such a result for all purposes, once the State has accepted the rule for ordinary attachment or garnishment.

11 See Pierce v. Pierce, 153 Ore. 248, 56 P. 2d 336; Farrar v. American Express Co., 219 S.W. 989; Morrison v. Illinois Central B. Co., 101 Neb. 49, 161 N.W. 1032; Shuttle-worth & Co. v. Marx & Co., 159 Ala. 418, 49 So. 83; Steer v. Dow, 75 N.H. 95, 71 Atl. 217; Harvey v. Thompson, 128 Ga. 147, 57 S.E. 104; Baltimore & Ohio R. Co. v. Allen, 58 W. Va. 388, 52 S.E. 465; see also Cross v. Brown, Steese & Clarke, 19 R.I. 220, 33 Atl. 147, affirmed sub nom. King v. Cross, 175 U.S. 396.

12 See Grant County Service Bureau, Inc. v. Treweek, 19 Wis. 2d 548, 554, 120 N.W. 2d 634, 638-639 (dictum); Godfrey Coal Co. v. Gray, 296 Mass. 323, 5 N.E. 2d 556; Steer v. Dow, supra; Graf v. Wilson, 62 Ore. 476, 125 Pac. 1005; Baltimore & Ohio B. Co. v. Alien, supra; but cf. Commercial Nat. Bank of Chicago v. Chicago, M & St. P.R. Co., 45 Wis. 172; Morphet v. Morphet, 19 Ill. App. 2d 304.

13 There is a distinguishing feature between the factual situation here and those in the New York decisions applying the “separate entity” doctrine in the bank’s favor. In the present case, unlike Bluebird Undergarment Corp. v. Gomez, 139 Misc. 742, 249 N.Y.S. 319, and Clinton Trust Co. v. Compania Aeucarera Central Mabay S.A., 172 Misc. 148, 14 N.Y.S. 2d 743, affirmed, 258 App. Div. 780, 15 N.Y.S. 2d 721, it affirmatively appears in the record that respondent’s central office participated in the transfer of the funds to the foreign branch. The New York doctrine appears to be based on the “intolerable burden” (Cronan v. Schilling, 100 N.Y.S. 2d 474, 476, affirmed, 282 App. Div. 940, 126 N.Y.S. 2d 192) or “crippling effect” (Newtown Jackson Co. v. Anvmmhawn, 148 N.Y.S. 2d 66, 68) which would be imposed on banks if they were required to notify all branches of any writs of attachment or garnishment that had been served upon them. It might well be sufficiently less burdensome today for a central office to notify the one branch to which it had transferred funds that attachment proceedings were pending to warrant a different result when, as here, the central office has sent the funds to the branch in the first instance. The result in Sokoloff v. National City Bank, 130 Misc. 66, 224 N.Y.S. 102, affirmed, 223 App. Div. 754, 227 N.Y.S. 907, affirmed, 250 N.Y. 69, 164 N.E. 745, where the central office did participate in tike transfer to the foreign branch, is not inconsistent with this suggested distinction since the court in Sokoloff concluded that the deposit could be reached on other grounds. Consequently, it is possible that even the New York courts would not find it necessary to extend the “separate entity” doctrine to cover the present factual situation.

14 Similar to these are other cases in which it was held that formal acts which must be performed by taxpayers need not be done by the government before a tax lien attaches. See Untied States v. Bowery Savings Bank, 297 F. 2d 380 (C.A. 2); United States v. Mainufactures Trust Co., 198 F. 2d 366 (C.A. 2); United States v. Emigrant Industrial Sav. Bank, 122 F. Supp. 547 (S.D. N.Y.); United States v. Buia, 144 F. Supp. 477 (S.D. N.Y.) (presentation of a passbook for a bank deposit). See also United States v. Schuermann, 106 F. Supp. 86 (E.D. Mo.); United States v. Oaldwell, 74 F. Supp. 114 (M.D. Tenn.) (surrender of a negotiable instrument).

15 It is no answer to this argument to say that the debt in the present case—unlike those in the life insurance and trust cases—is payable in the first instance in a foreign jurisdiction. As has been noted above, pp. 24-28, supra, the location at which the debt is payable is no limitation on the court’s jurisdiction quasi in rem.

16 The possibility that an action might be brought in the foreign jurisdiction for slander of credit if respondent, in compliance with the order, refuses to release the funds on deposit, presupposes that respondent has a legal obligation in that jurisdiction to permit withdrawal of the funds notwithstanding the order of a United States District Court. Kespondent’s failure to prove that “freezing” of the assets would result in “a violation of foreign law” indicates—in the absence of evidence to the contrary—that the foreign jurisdiction would accept the generally recognized defense to such an action that an outstanding court order prohibited payment on the depositor’s account. See Comment, Bank Responsibility to Third Party Claimant Against Depositor’s Account, 30 Marq. L. Eev. 54,61 (1946).

17 Even a foreign court which would not enforce an unexecuted United States judgment arising out of a tax claim, see, e.g., United States of America v. Harden, Supreme Court of Canada, October 2, 1963, 63-2 U.S.T.C. ¶9768, would recognize a transfer of property “fully executed” under U.S. law pursuant to such a judgment. See Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398, 414.

18 See, e.g., Karp v. First National Bank, 295 Mass. 365, 3 N.E. 2d 733; Riley v. State Bank of De Pere, 223 Wis. 16, 269 N.W. 722. See generally Note, Double Liability of Garnishees Resulting From Failure of Jurisdiction, 48 Yale L. J. 690 (1939); Annot., 49 A.L.R. 1411, 166 A.L.R. 272.

19 H. Rep. No. 2047, 87th Cong., 2d Sess., p. 2.