No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

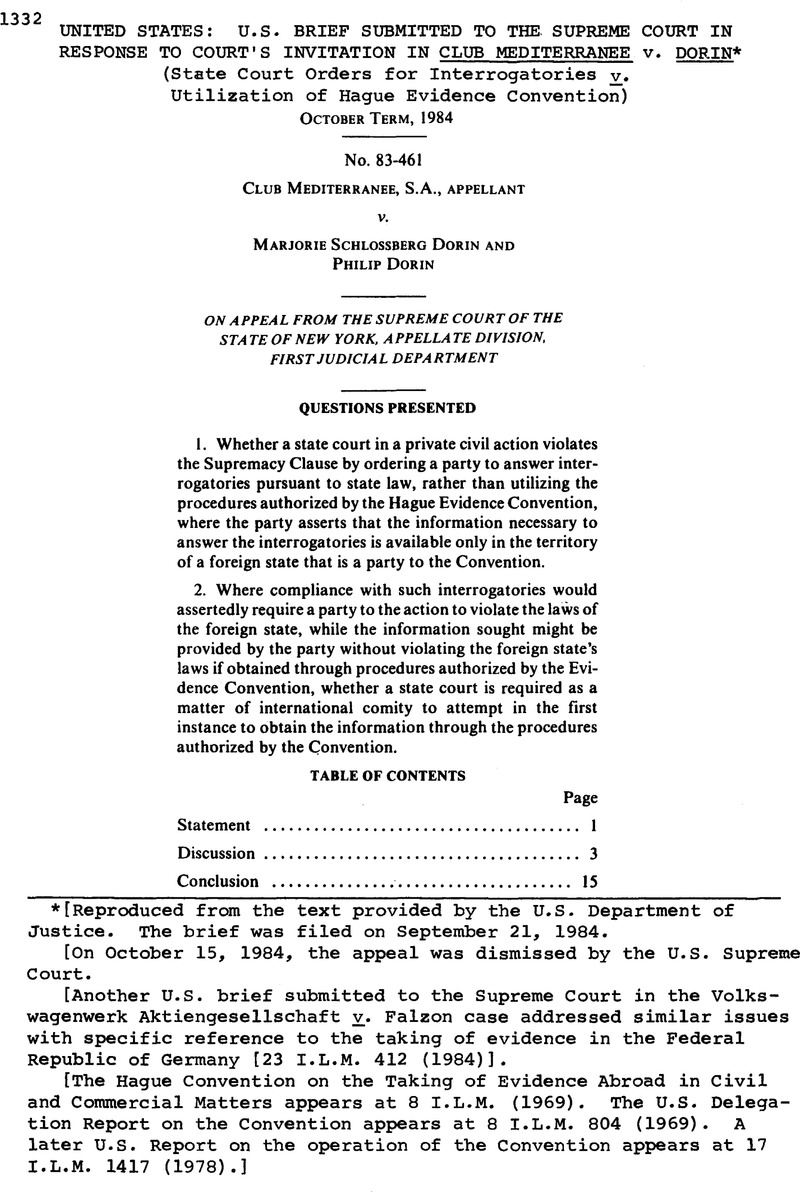

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Department of Justice. The brief was filed on September 21, 1984.

[On October 15, 1984, the appeal was dismissed by the U.S. Supreme Court.

[Another U.S. brief submitted to the Supreme Court in the Volkswagenwerk Aktiengesellschaft v. Falzon case addressed similar issues with specific reference to the taking of evidence in the Federal Republic of Germany [23 I.L.M. 412 (1984)].

[The Hague Convention on the Taking of Evidence Abroad in Civil and Commercial Matters appears at 8 I.L.M. (1969). The U.S. Delegation Report on the Convention appears at 8 I.L.M. 804 (1969) . A later U.S. Report on the operation of the Convention appears at 17 I.L.M. 1417 (1978).]

1 Under New York law, [i]nterrogatories shall be answered in writing under oath by the party upon whom served, if an individual, or, if the party served is a corporation, a partnership, or a sole proprietorship, by any officer, director, agent or employee having the information.

N.Y. Civ. Prac. R. 3134(a) (McKinney 1970).

2 The interrogatories seek information concerning (1) Club Med's relationship with the facility in Haiti, including all documents that describe that relationship; (2) construction of the Club Med facility in Haiti; (3) the existence of an operational manual for the facility; (4) whether employees are required to take appropriate shots for typhoid fever and malaria; (5) whether the Haiti facility's sanitation, food storage and preparation, and water systems have been inspected, and the results of such inspections; (6) management and medical personnel at the Haiti facility (J.S. App. 97a-101a).

3 The French statute cited by Club Med, Law No. 80-538 of July 16, 1980, Art. 1 bis, is set forth at page 12, infra.

4 The Chief Justice subsequently stayed the trial court's order pending this Court's consideration of the instant appeal (J.S. App. 17a).

5 We note that this Court appears to lack jurisdiction over this case except by way of certiorari under 28 U.S.C 1257(3), as requested in the alternative by appellant pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 2103 (see J.S. 22). Appellate jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. 1257(1) clearly is not appropriate here, because the state courts have issued no decision in this case against the validity of a treaty. Similarly, jurisdiction by way of appeal under 28 U.S.C. 1257(2) also is unavailable. The record, as reflected in the papers filed in this Court, does not reveal that appellant explicitly challenged the validity of the New York statute as applied, but rather shows that appellant attacked the particular actions of the trial court as invalid on federal grounds. There is therefore no jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. 1257(2). See Richmond Newspapers, Inc. v. Virginia, 448 U.S. 555, 562-563 n.4 (1980) (plurality opinion); Hanson v. Denckla, 357 U.S. 235,244 & n.4 (1958); Charleston Federal Savings & Loan Ass’n v. Alderson, 324 U.S. 182,185-187 (1945). This case, like virtually every case, involves judicial actions taken pursuant to procedures established by statute or rule. No distinction in the statute itself is challenged, as in Mayer v. Cityof Chicago, 404 U.S. 189 (1971), and In re Griffiths, 413 U.S. 717,718 (1973), and no assertedly unconstitutional application of a substantive state statute is involved, as in Japan Line, Ltd. v. County of Los Angeles, 441 U.S. 434,440-441 (1979),and Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15, 17-18(1971).

6 Because the second and third methods do not involve proceedings before a judge of the host country, they are subject to strict limitations in the Convention. See S. Exec. Rep. 92-25, supra, at 4-5.

7 Hague Convention on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil and Commercial Matters, Nov. IS, I96S, 20 U.S.T. 361.T.I.A.S. No. 6638, entered into force for the United States, February 10, 1969.

8 Article 1 of the Service Convention (20 U.S.T. at 362) provides: “The present Convention shall apply in all cases in civil or commercial matters where there is occasion to transmit a judicial or extrajudicial document for service abroad.”

9 Article 23 provides that a contracting state may “declare that it will not execute Letters of Request issued for the purpose of obtaining pre-trial discovery of documents as known in Common Law countries” (J.S. App. 28a).

10 We recognize that in our brief in Volkswagenwerk, A.G. v. Falzon, No. 82-1888 (at 6), we stated:

The parties to the Convention contemplated that proceedings not authorized by the Convention would not be permitted. The Convention accordingly must be interpreted to preclude an evidence taking proceeding in the territory of a foreign state party if the Convention does not authorize it and the host country does not otherwise permit it.

After further reflection, we believe that that statement requires clarification to the extent that it could be construed to mean that the Convention is exclusive.

We note that the above statement was not necessary to our argument that the trial court's order in Falzon was unlawful. The trial court in Falzon ordered that employees of a foreign corporation be deposed in Germany before an American consular officer. Under established principles of both domestic and international law, however, American courts are precluded from ordering anyone to participate in discovery proceedings in the territory of a foreign state absent that state's consent, wholly independent of the Evidence Convention. See Oxman, supra, 37 U. Miami L. Rev. at 751. Because Germany's consent to such discovery was limited to means authorized by the Convention, the court in Falzon could order such proceedings in Germany only if authorized by the Convention.

11 See also Restatement (Revised) of Foreign Relations Law of the United States § 420 (Tent. Draft No. 3, 1982):

Requests for Disclosure and Foreign Government Compulsion.

(1)(a) Where authorized by statute or rule of court,, a court in the United States may order a person before the court to produce documents or other information directly relevant, necessary, and material to an action or investigation, even if the information or the person in possession of the information is located outside the United States.

(b) Failure to comply with an order to produce information may subject the person to whom the order is directed to sanctions, including contempt or dismissal of a claim or defense, or to a finding by the court that the facts to which the order was addressed are as asserted by the opposing party.

(c) In issuing an order directing production of documents or other information located abroad, a court in the United States must take into account the importance to the investigation or litigation of the documents or other information requested; the degree of specificity of the request; in which of the states involved the documents or information originated; the extent to which compliance with the request would undermine important interests of the state where the information is located; and the possibility of alternative means of securing the information.

(2) If disclosure of information located outside the United States is prohibited by a law or regulation of the state in which the information or prospective witness is located, or by the state of nationality of the prospective witness,

(a)the person to whom the order is directed may be required by the court to make a good faith effort to secure permission from the foreign authorities to make the information available;

(b) the court may not ordinarily impose the sanction of contempt, dismissal, or default on the party that has failed to comply with the order for production, except in cases of deliberate concealment or removal of information or of failure to make a good faith effort in accordance with paragraph (a);

(c)the court may, in appropriate cases, make findings of fact adverse to a party that has failed to comply with the order for production, even if that party has made a good faith effort to secure permission from the foreign authorities to make the information available and that effort has been unsuccessful.

12 The Evidence Convention, by its terms, applies only to civil and commercial litigation, and not to criminal or quasi-criminal investigations and enforcement proceedings conducted by governmental entities. Consequently, this case does not present any issue concerning the use of grand jury subpoenas or administrative summonses to obtain records located in foreign countries. See, e.g.,Marc Rich & Co., A.G. v. United States, 707 F.2d 663 (2d Cir. 1983), cert, denied, No. 82-2011 (June 27, 1983); United States v. Vetco, Inc., supra; In re Grand Jury Proceedings (Bank of Nova Scotia), 691 F.2d 1384 (11th Cir. 1982), cert, denied, No. 82-1531 (June 13, 1983).

13 For purposes of this brief, we have assumed that, because of the federal government's overriding interest in foreign relations, the validity of the state court's discovery order under principles of international comity is a question of federal common law and is ultimately reviewable in this Court. See Banco Nacionaide Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398, 424-427 (1964); Zschernig v. Miller, 389 U.S. 429 (1968); Oxman, supra, 37 U. Miami L. Rev. at 789-790 n. 151.