No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

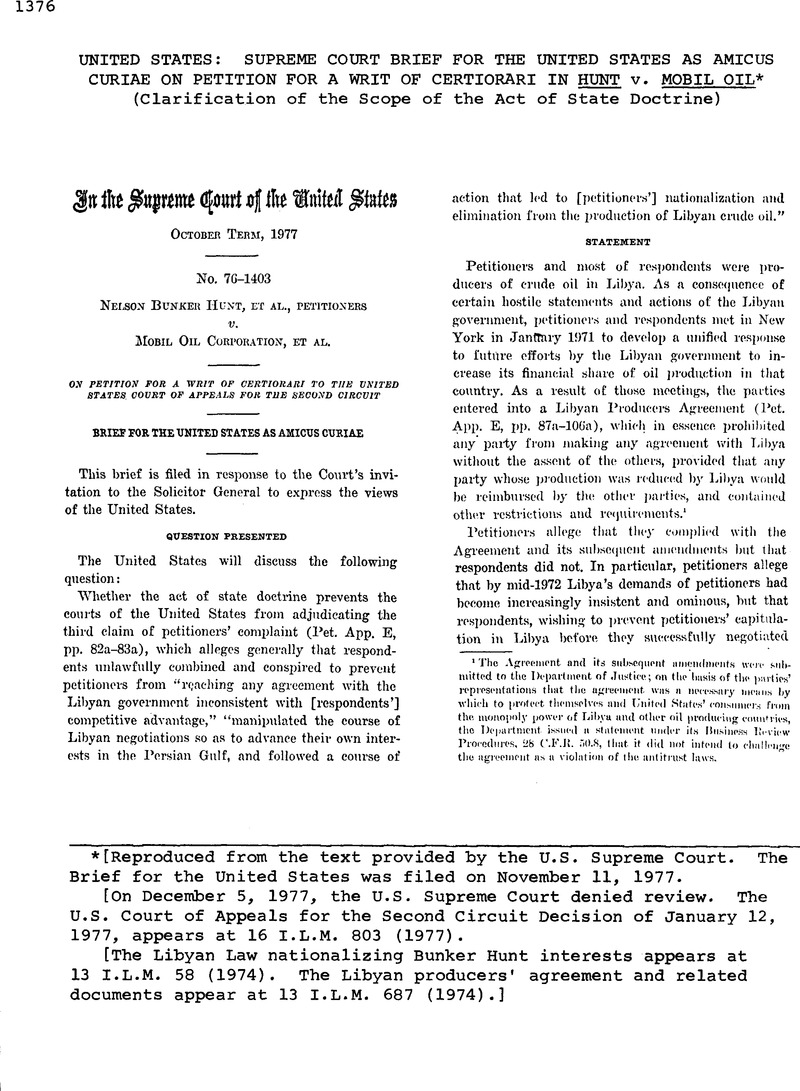

United States: Supreme Court Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae on Petition for a Writ of Certiorari in Hunt v. Mobil Oil (Clarification of the Scope of the Act of State Doctrine)*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1977

Footnotes

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Supreme Court. The Brief for the United States was filed on November 11, 1977.

[On December 5, 1977, the U.S. Supreme Court denied review. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Decision of January 12, 1977, appears at 16 I.L.M. 803 (1977).

[The Libyan Law nationalizing Bunker Hunt interests appears at 13 I.L.M. 58 (1974). The Libyan producers' agreement and related documents appear at 13 I.L.M. 687 (1974).]

References

page 1376 note 1 The Agreement and its subsequent amendments were submitted to the Department of Justice; on the basis of the parties’ representations that the agreement was a necessary means by which to protect themselves and United States’ consumers from the, monopoly power of Libya and other oil producing countries, the Department, issued a statement under its business Review Procedures, 28 C.F.R. 50.8, that it did not intend to challenge the agreement as a violation of the antitrust laws.

page 1377 note 2 One of the difficulties in understanding the complaint in the absence of evidence concerns the relationship between the third claim and the first, second and fourth claims, which were not dismissed. From petitioners’ explanation of the facts it would appear that their injury resulted not from the expropriation per se but, from the expropriation and respondents’ subsequent alleged breach of their contractual obligations to petitioners under the Libyan Producers Agreement, which respondents allegedly conspired to breach for anticompetitive reasons, and from anticompetitive requirements that the Agreement imposed on petitioners (Pet. 6-11). The alleged breach of contract, conceited refusals to deal, and imposition of anticompetitive terms are separately alleged in the first, second and fourth claims, however, and the expropriation is a necessary precondition of each. It is difficult to see, therefore, to what extent the third claim does not merely restate, the claims that have not been dismissed. The answer may depend on the development, of evidence.

These difficulties illustrate the wisdom of the principle, reaffirmed by this Court last Term, that, particularly in antitrust cases, “dismissals prior to giving tho plaintiff ample opportunity for discovery should be granted very sparingly.” Hospital Building Co. v. Trustees of Rex Hospital, 425 U.S. 738, 746.

page 1377 note 3 See Pet. 6-ll. Thus petitioners state: “Hunt faithfully performed its side of the bargain; it rejected Libya’ demands—despite Libya’ tempting offer of special considerations were Hunt the first to agree to 51 per cent participation. And Hunt paid the price of fidelity; in the spring of 1973 it was first shut in and later nationalized” (Pet. 11).

But later petitioners seem to place different and somewhat inconsistent constructions on the complaint. They assert that “[respondents’ efforts to disadvantage petitioners] was achieved long before the Libyan government nationalized Hunt on June 11, 1973” (Pet. 22); that “[respondents’] aims * * * were largely achieved whether or not the Libyan government ever nationalized Hunt—which came as an added bonus” (Pet. 23); and that “if Hunt, relying upon [respondents’] assurances, did take positions which led to its nationalization, it matters not what the motivation of the, Libyan government was or what the Libyan government would have done in other circumstances” (Pet. 24). This latter statement in particular seems to be a contradiction in terms. Since petitioners must prove that the positions they took “led” to their nationalization, the motives of the Libyan government in nationalizing them is directly relevant to their claim.

page 1378 note 4 Thus petitioners appear to be inaccurate in analogizing the third claim to a conspiracy among certain parties to eliminate a competitor by persuading him to sleep in a street where they anticipate the passage of a mail truck by falsely representing to him that the street will be closed to traffic (Pet. 24). Such a case does not involve action by the victim that prompts the instrument of the injury to do the injury, and a complaint arising out of that hypothetical set of facts would not require proof of the mail truck driver’ motives in taking one route rather than another, or no route at all. Petitioners’ third claim, however, appears to require proof that the Libyan government would not have taken the action it took against petitioners if they had not refused to negotiate.

page 1378 note 5 We express no view on petitioners’ ability to prove the third claim at trial or on any factual or other legal defenses respondents might raise.

page 1378 note 6 See also Ali, Restatement (Second), Foreign Relations Law of the United States §41 (1965): “A court in the United States * * * will refrain from examining the validity of an act of a foreign state by which that state has exercised its jurisdiction to give effect to its public interests” (emphasis supplied).

page 1378 note 7 It appears that both the Libyan government and the United Slates government explained the nationalization of petitioners’ properly simply as an act of political reprisal against the interests of the United States and its citizens (Pet. App. A, p. 10a).

page 1378 note 8 Unlikely as it might appear, respondents might attempt to prove that the expropriation was in fact motivated, for example, by petitioners’ failure to comply with Libyan safety regulations, or by personal animosity against petitioners.

page 1379 note 9 In many ordinary tort or contract cases, it may be open to the defendant to allege and offer proof that the proximate cause of the plaintiff’ injury was the act, not of the defendant, but of a foreign sovereign.

page 1379 note 10 A complaint that requires proof of the motives underlying a foreign government’ act may raise substantial problems of proof. See Pet. App. A. p. 19a. Cf. Fed. R. Civ. P. 44.1. Hut the possibility of such problems is not a sufficient reason to prevent the plaintiff from trying. As this Court noted in Continental Ore Co. v. Union Carbide Carbon Corp., 370 U.S. 800, 97, 701, the jury must be permitted to draw appropriate inferences concerning causation from the circumstantial evidence presented.

page 1379 note 11 Moreover, such a construction apparently would confer antitrust, immunity on acts by private defendants in violation of the law of foreign state (e.g., procuring governmental acts by bribery). It would also confer antitrust immunity on acts of a kind that would not be so immune if the governmental act in question were that of the United States or one of its agencies or officers, since successful efforts by private parties to bring about domestic governmental acts are not automatically immune from antitrust liability. See Cantor v. Detroit Edison Co., 428 U.S. 579; California, Motor Motor Co. v. Trurking Unlimited, 404 U.S. 308; Georgia v. Pennsylvania R. Co., 324 U.S. 439; note 13, infra.

page 1379 note 12 The Court purported to distinguish American Banana on the ground that the acts complained of there had occurred within a foreign state, whereas the conspiracy alleged in Sisal Sales was entered into and made effective by acts done in the United States. However, the rationale of the act of state doctrine does not depend on the situs of the conspiracy or of the acts of private defendants. In some cases, the threshold question of whether foreign rather than American law governs a case depends on the locus of the private acts or the predominant jurisdictional contacts of the transactions, and in such cases, the jurisdictional contacts may be relevant to whether the act of state doctrine is implicated at nil. But since American antitrust law is now understood as having extraterritorial application, in antitrust cases the locus of the defendants’ acts does not determine which sovereign’ law applies and thus would seem largely irrelevant to concerns relating to act of state principles.

page 1380 note 13 The apparent inconsistency between American Banana and subsequent cases has created some uncertainty among the lower courts. In Occidental Petroleum Corp. v. Buttes Gas & Oil Co., 331 F. Supp. 92 (C.D. Cal.), affirmed, 461. F. 2d 1261 (C. A. 9) , certionari denied. 109 U.S. 950, the court, relying on American Banana, dismissed an antitrust complaint that alleged, inter alia, that the defendants had induced one sovereign to assert dominion over territory within a concession awarded to plaintiff by another sovereign. In Timberlane Lumber Co. v. Bank of America, N.T. & S. A., 549 F. 2d 597, however, the court upheld a complaint that, alleged, inter alia, that the defendants had used Hondurnn judicial process for anticompettive purposes to injure the plaintiff.

The controversy between the parties in the Occidental Petroleum case subsequently arose in the courts of the United Kingdom, and the judges of the Court of Appeal, Civil Division, came to a conclusion contrary to the Ninth Circuit’ in that case concerning the application of the net of state doctrine, in well-reasoned opinious that analyzed, correctly in our view, the distinctions between the act of state doctrine and other related doctrines. Buttes Gas and Oil Co. v. Hammer [1975] 2 All E.R. 54.

page 1380 note 14 When, as here, the complaint in a private antitrust action will not require a court to determine the validity of a foreign state’ act that the defendant is alleged to have brought about, we believe that the appropriate analysis is not under the act of state doctrine but under state-action doctrines developed in decisions under the anti-trust laws. The application of those doctrines to acts of foreign states is not firmly settled, but it would not appear that petitioner’ third claim in this case would come within those doctrine in any event.

Petitioners’ complaint on its face does not establish that respondents alleged conduct was under the compulsion of foreign law (cf. Parker v. Brona, 317 U.S. 341) or constituted a legitimate effort to persuade a foreign government to adopt certain measures (see Eastern Railways Presidents Conference v. Noerr Motor Freight, Inc., 365 U.S. 127; United Mike Workers of America v. Pennington, 381 U. S. 657). If respondents seek the benefits of state action doctrines (and to avoid their limitations, see cases cited in note 11 supra), it is incumbent upon them to establish the necessary facts.