No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

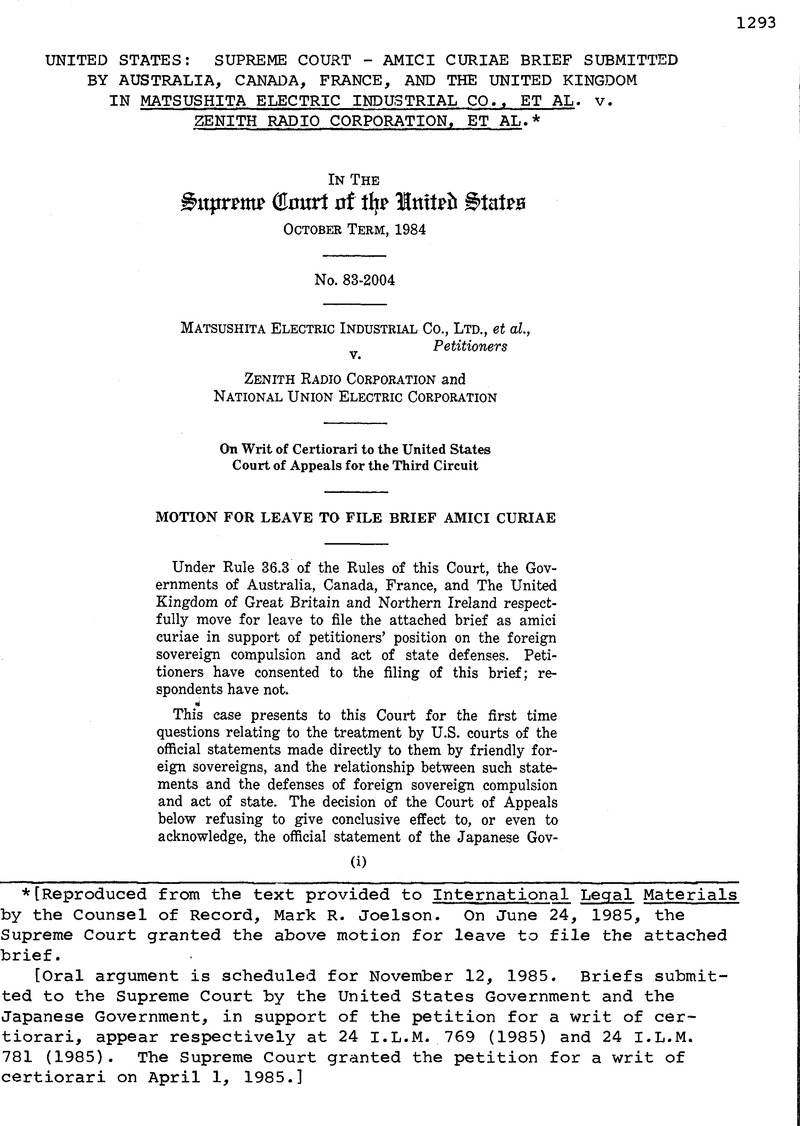

* [Reproduced from the text provided to International Legal Materials by the Counsel of Record, Mark R. Joelson. On June 24, 1985, the Supreme Court granted the above motion for leave to file the attached brief.

[Oral argument is scheduled for November 12, 1985. Briefs submitted to the Supreme Court by the United States Government and the Japanese Government, in support of the petition for a writ of certiorari, appear respectively at 24 I.L.M. 769 (1985) and 24 I.L.M. 781 (1985). The Supreme Court granted the petition for a writ of certiorari on April 1, 1985.]

* [Not reproduced.]

1 Amici did advise the Department of State of their serious concern about the Court of Appeals' treatment of the act of state and foreign sovereign compulsion issues. The Solicitor General lodged copies of amici's statements with the Clerk of the Court in connection with the filing of the petition for a writ of certiorari.

2 For an acknowledgement of these difficulties, see Sec. of State George P. Shultz, Trade, Interdependence and Conflicts of Jurisdiction, Address before the S. Car. Bar Ass'n in Columbia (May 5, 1984), reprinted in Dept. of State Bulletin, June 1984, a t 33. See also Perspectives on the Extraterritorial Application of U.S. Antitrust and Other Laws(J. Griffin ed. 1979).

3 On May 18, 1984, Ministers comprising the Council of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, including the U.S. Secretary of State, agreed to strengthen bilateral and multilateral cooperation in intergovernmental conflicts involving multinational enterprises by strongly encouraging governments to follow an approach of cooperation, moderation and restraint, rather than unilateral action. See Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, International Investment and Multinational Enterprises: The 1984 Review of the 1976 Declaration and Decisions 26 (1984); see also Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Recommendation of the Council Concerning Cooperation Between Member Countries on Restrictive Business Practices Affecting International Trade, OECD Doc. C (1979) 154 (1979).

4 Agreement Between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of Australia Relating to Cooperation on Antitrust Matters (June 29, 1982), reprinted in [1969-83 Current Comment Transfer Binder] Trade Reg. Rep. (CCH) ¶ 50,440.

5 Memorandum of Understanding Between the Government of Canada and the Government of the United States of America as to Notification, Consultation and Cooperation with Respect to the Application of National Antitrust Laws (Mar. 9, 1984), reprinted in 5 Trade Reg. Rep. (CCH)¶ 50,464.

6 Letter from Solicitor General McCree to Legal Adviser Hansell (May 2, 1978), printed in 1978 Dept. of State Digest of United States Practice in International Law 561, reprinted in part in 73 Am. J. Int'l L. 122,125 (1979).

7 Dept. of State, Circular Diplomatic Note to Chiefs of Mission in Washington, D.C. (Aug. 17, 1978), printed in 1978 Dept. of State Digest of United States Practice in International Law 560, reprinted in part in73 Am. J. Int'l L. 122, 124 (1979). See also Letter from Deputy Legal Adviser Marks (June 15, 1979), described in 73 Am. J. Int'l L. 669, 678-79 (1979).

8 The court described the foreign governments as “surrogates” for non-appearing defendants and added “shockingly to us, the governments of the defaulters have subserviently presented for them their case against the exercise of jurisdiction.” In re Uranium Antitrust Litigation, 617 F.2d 1248, 1256 (7th Cir. 1980).

9 Letter from Legal Adviser Owen to Assistant Attorney General Shenefleld (Mar. 17, 1980). For background and a substantial text of the letter, see 74 Am. J. Inf'l L. 657, 665-67 (1980).

“The sovereignty and equality of states represent the basic constitutional doctrine of the law of nations . . . . The principal corollaries of the sovereignty and equality of states are: (1) a jurisdiction, prima facie exclusive, over a territory . . .; (2) a duty of nonintervention in the area of exclusive jurisdiction of other states . . . .” Brownlie, I. Principles of Public International Law 287 (3d ed. 1979)Google Scholar.

11 “Anticompetitive practices compelled by foreign nations are not restraints of commerce, as commerce is understood in the Sherman Act, because refusal to comply would put an end to commerce.” Interamerican Refining Corp. v. Texaco Maracaibo, Inc., 307 F. Supp. 1291,1298 (D. Del. 1970).

12 Timberlane Lumber Co. v. Bank of America N.T. & S.A., 549 F.2d 597, 606 (9th Cir. 1976).

13 In Southern Motor Carriers Rate Conference, Inc. v. United States, 105 S. Ct 1721, 1730 (1985), this Court was faced with the task of determining whether, in the absence of a Mississippi statute expressly permitting the challenged conduct, the state had clearly articulated a policy to displace competition with a regulatory structure. The Court relied on the State of Mississippi's Amicus Curiae Brief in the District Court to hold that the state commission had actively encouraged collective ratemaking.

14 Banco National de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398, 416 (1964).

15 It also should be noted that Section 2-615 (a) of the Uniform Commercial Code provides in part that “compliance in good faith with any applicable foreign or domestic governmental regulation or order whether or not it later proves to be invalid” excuses nonperformance. This section has been held to excuse non-performance based on an informal U.S. Government procurement program. Eastern Air Lines, Inc. v. McDonnell Douglas Corp., 532 F. 2d 957, 996 (5th Cir. 1976).

16 The Court recently held that, in the state action immunity context, a private party acting pursuant to an anticompetitive state regulatory program need not “point to a specific, detailed legislative authorization” of its challenged conduct but may rely on an express intent to displace competition in a particular field with a regulatory structure. Southern Motor Carriers Rate Conference, Inc. v. United States, 105 S. Ct. at 1730-31 (quoting City of Lafayette v. Louisiana Power & Light Co., 435 U.S. 389, 415 (1978) ).

17 See, e.g., Lowe, A. V. Extraterritorial Jurisdiction: An Annotated Collection of Legal Materials (1983)Google Scholar; Meessen, Antitrust Jurisdiction Under Customary International Law, 78 Am. J. Int'l L. 783 (1984)Google Scholar; Cira, , The Challenge of Foreign Laws to Block American Antitrust Actions, 18 Stan. J. Int'l L. 247 (1982)Google Scholar.

18 For a recommendation of swift action, see 2 Atwood, J. R. & Brewster, K. Antitrust and American Business Abroad 348 (2d ed. 1981)Google Scholar.