Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

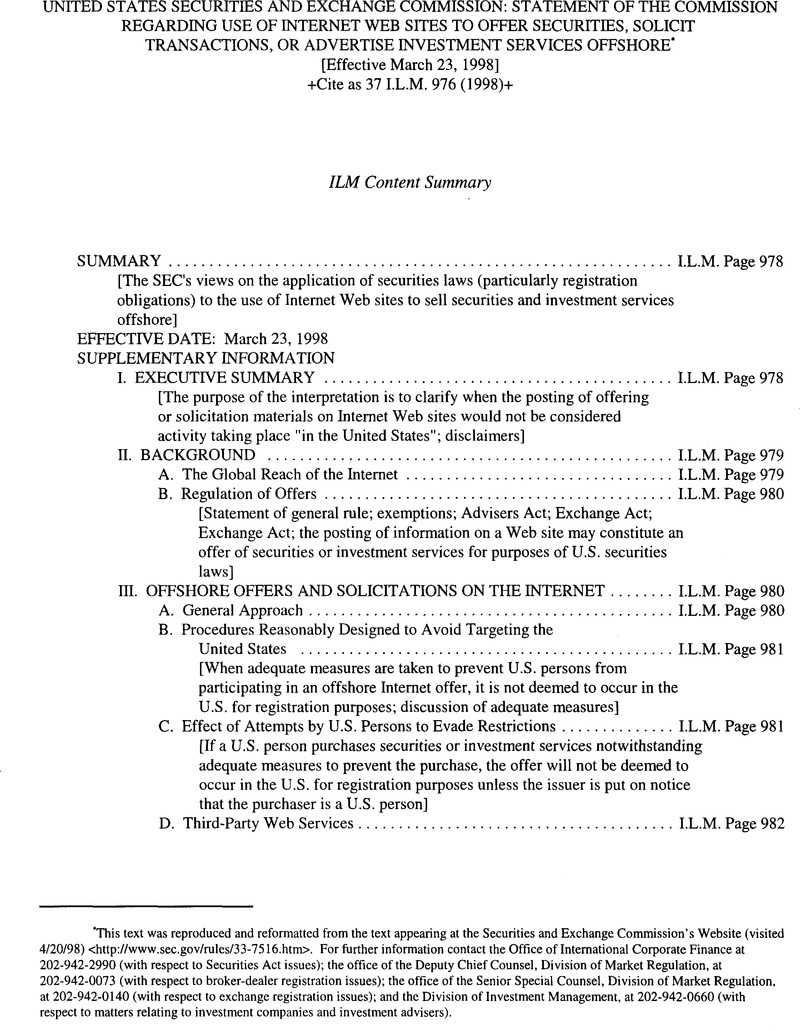

* This text was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the Securities and Exchange Commission's Website (visited 4/20/98) <http://www.sec.gov/rules/33-7516.htm>. For further information contact the Office of International Corporate Finance at 202-942-2990 (with respect to Securities Act issues); the office of the Deputy Chief Counsel, Division of Market Regulation, at 202-942-0073 (with respect to broker-dealer registration issues); the office of the Senior Special Counsel, Division of Market Regulation, at 202-942-0140 (with respect to exchange registration issues); and the Division of Investment Management, at 202-942-0660 (with respect to matters relating to investment companies and investment advisers).

1 15 U.S.C. 77a, et seq. (the “Securities Act“).

2 15 U.S.C. 80a-1, et seq. (the “Investment Company Act“).

3 15 U.S.C. 80b-1, et seq. (the “Advisers Act“).

4 15 U.S.C. 78a, et seq. (the “Exchange Act“).

5 The courts have recognized U.S. jurisdiction over fraudulent conduct where substantial conduct or effects occur in the United States. See generally Itoba Ltd. v. LEP Group PLC , 54 F.3d 118 (2d Cir. 1995), cert, denied, 516 U.S. 1044 (1996) and Robinson v. TCI/US West Communications Inc., 117 F.3d 900 (5th Cir. 1997) (citing Schoenbaum v. Firstbrook , 405 F.2d 200 (2d Cir.), rev'd on other grounds on rehrg. en bane , 405 F.2d 215 (2d Cir. 1968), cert, denied , 395 U.S. 906 (1969) (effects test)); Bersch v. Drexel Firestone Inc., 519 F.2d 974 (2d Cir.), cert, denied , 423 U.S. 1018 (1975) (conduct test); Leasco Data Processing Equipment Corp. v. Maxwell, 468 F.2d 1326 (2d Cir. 1972) (conduct test).

6 See President William J. Clinton and Vice President Albert Gore, Jr., A Framework for Global Electronic Commerce (1997), http://www.iitf.nist.gov/eleccomm/ecomm.htm; European Ministerial Conference, “Global Information Networks: Realizing the Potential,” July 6-8, 1997, Ministerial Declaration, Global Informational Networks,.

7 For a discussion of recent Commission actions addressing the Internet, see The Impact of Recent Technological Advances on the Securities Markets , Report prepared by the Staff of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission pursuant to Section 510(a) of the National Securities Markets Improvements Act of 1996 (Oct. 1997) http://www.sec.gov/news/studies/techrp97.htm.

8 Wilske and Schiller, International Jurisdiction in Cyberspace: Which States May Regulate the Internet?, http://www.law.indiana.edu/fclj/pubs/v50/nol/wilske.html, Section II.A.2.(c).

9 The Web site sponsor can aid Internet searches by adding “tags” to its Web site that facilitate a search engine identifying the site as containing information relating to targeted topics. Generally, we will not view the use of tags relating to securities or investments as transforming the Web site into a targeted communication that would require additional measures to assure against sales to U.S. persons, such as blocking access by U.S. persons to the offering materials.

10 Section 5 of the Securities Act, 15 U.S.C. 77e.

11 See, e.g., Section 4(2) of the Securities Act, 15 U.S.C. 77d(2); Regulation D (17 CFR 230.501-508).

12 Section 7(d) of the Investment Company Act, 15 U.S.C. 80a-7(d).

13 See Section 3(c)(l) and Section 3(c)(7) of the Investment Company Act, 15 U.S.C. 80a-3(c)(l), 15 U.S.C. 80a-3(c)(7). See also Staff no-action letter, Goodwin, Procter & Hoar (available Feb. 28, 1997) (“Goodwin Procter“).

14 Section 203(a) of the Advisers Act, 15 U.S.C. 80b-3(a).

15 Section 15(a) of the Exchange Act, 15 U.S.C. 78o(a).

16 Section 6 of the Exchange Act, 15 U.S.C. 78f.

17 See , e.g., Securities Act Release No. 7233, Question 20 (Oct. 6, 1995) (60 FR 53458) (“The placing of the offering materials on the Internet would not be consistent with the prohibition against general solicitation or advertising in Rule 502(c) of Regulation D.“).

18 We also assume that the Internet is an instrument of interstate commerce and that its use satisfies the “jurisdictional means” requirements of the federal securities laws. See American Library Ass'n v. Pataki, 969 F. Supp. 160, 161 (S.D.N.Y. 1997).

19 Under a resolution adopted by the North American Securities Administrators Association (“NASAA“), states are encouraged to take appropriate steps to exempt Internet offers from the registration provisions of their securities laws when the offers indicate that the securities are not being offered to residents of their state and the offers are not otherwise specifically made to any persons in their state. Sales of the securities that were the subject of the Internet offer could be made in that state after the offering has been registered and the final prospectus has been delivered to investors, or where the sales are exempt from registration. NASAA, Resolution Regarding Securities Offered on the Internet (adopted Jan. 7, 1996), 1996 CCH Par. 7040 (Jan. 1996). According to NASAA, 32 states have implemented the resolution and 15 states have indicated an intent to do so. Several foreign authorities have provided guidance on Internet and securities related issues. See , e.g., Policy Statement 107 on Electronic Prospectuses (Sept. 1996) http://www.asc.gov.au (Australia); Notice and Interpretation Note, Trading Securities and Providing Advice Respecting Securities on the Internet (Mar. 3, 1997), NIN #97/9 (British Columbia, Canada).

20 We use the term “U.S. person” as it is defined in Rule 902(k) of Regulation S under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.902(k)), which is premised on residence in the United States, regardless of any temporary presence outside the United States. See Securities Act Release No. 7505 (Feb. 18, 1998) (63 FR 9632 (Feb. 25, 1998)) (renumbering CFR sections). “U.S. person” generally has the same meaning for purposes of Section 7(d) of the Investment Company Act as under Rule 902(k) of Regulation S under the Securities Act. See Goodwin Procter, supra note 13. For purposes of this release, we deem Internet offers “targeted at the United States” to include Internet offers targeted to U.S. persons. Cf. Rule 902(h)(2) of Regulation S (17 CFR 230.902(h)(2)) (offers targeting identifiable groups of U.S. persons offshore are not offshore transactions).

21 The disclaimer would have to be meaningful. For example, the disclaimer could state, “This offering is intended only to be available to residents of countries within the European Union.” Because of the global reach of the Internet, a disclaimer that simply states, “The offer is not being made in any jurisdiction in which the offer would or could be illegal,” however, would not be meaningful. In addition, if the disclaimer is not on the same screen as the offering material, or is not on a screen that must be viewed before a person can view the offering materials, it would not be meaningful.

22 In our view, while a relevant factor, the fact that an Internet offeror posts offering materials in English even though it is based in a non-English speaking country will not, by itself, demonstrate that the offer is targeted at the United States.

23 These additional steps could include a request for further evidence (e.g., a copy of a passport or driver's license).

24 Governmental authorities or securities exchanges could post issuer information that is required by law to be filed with them, including prospectuses, on their Web sites without restriction. Securities exchanges, however, should consider the U.S. registration implications of their Web sites as a whole. See infra Section VII.B.

25 Rule 502(c) under the Securities Act (17 CFR 240.502(c)).

26 Rule 902(c) (17 CFR 230.902(c)).

27 Rule 902(h) and Rule 903 of Regulation S (17 CFR 230.902(h) and 230.903). The issuer's or underwriter's use of an Internet Web site to offer securities will not, by itself, prevent bona fide offshore purchasers in a Regulation S offering from reselling into the United States pursuant to registration or an exemption, such as Rule 144A (17 CFR 230.144A), provided that: (1) those purchasers are not part of the selling group; (2) those purchasers are not affiliated with the issuer or any member of the selling group; and (3) the issuer's or underwriter's use of the Web site was not undertaken as part of an arrangement with, or on behalf of, such offshore purchasers.

28 To identify those persons who are responding to the Internet offer, the Web site could provide telephone numbers, contact persons, or addresses that differ from those used in the offeror's other, more traditional offering materials. Under an approach suggested in staff no-action letters, the offeror could communicate with U.S. persons on the list to determine whether they are accredited investors with a view towards permitting their participation in separate, future exempt U.S. offerings by the issuer or, where the Web site offeror is an intermediary, other issuers. See Staff no-action letters, Royce Exchange Fund (available Aug. 28, 1996); Bateman Eichler (available Dec. 3, 1985); E.F. Hutton & Co. (available Dec. 3, 1985); Woodtrails-Seattle (available Aug. 9, 1982). Likewise, any investor solicited by the issuer or underwriter prior to or independent of the Web site posting could participate in the private offer, regardless of whether the investor may have viewed the posted offshore offering materials.

29 This step could be accomplished in multiple ways. For example, when a person reaches the Web site and then attempts to move to a section that includes offering information, a screen could ask for the required residence information. After the user enters the information, the area code and address could be automatically and immediately screened to eliminate further access to those who match a U.S. area code or address. Alternatively, the offeror could require a password and not assign a password until it verifies that address information, or it could block access by using technology that recognizes the country from which the Web site is being accessed.

30 Web site offerers must act in good faith to screen U.S. persons from viewing offering information. A screening mechanism that suggests ways of easy bypass would not be evidence of good faith.

31 A foreign issuer that wishes to use an Internet Web site to conduct the concurrent private placement in the United States could follow the general procedures developed in the domestic context for private placements on the Internet. See , e.g., Staff no-action letters, IPONET (available July 26, 1996); Lamp Technologies, Inc. (available May 29, 1997). Under these procedures, the public offer posted on the Web site may not provide a hyperlink or otherwise alert the viewer to any Web site containing private placement offering materials.

32 Rule 135c under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.135c) provides useful guidance on what limited information could be included on the Web site under these circumstances.

33 We use the term “foreign issuer” as it is defined in Rule 902(e) of Regulation S (17 CFR 230.902(e)). See Securities Act Release No. 7505.

34 See , e.g., IPONET and Lamp Technologies, Inc., supra note 31. Our interpretation therefore would allow for the creation of limited-access systems. Eventually, closed systems may develop that target only non-U.S. persons and qualified U.S. investors.

35 See Securities Act Release No. 7392 at n.31 (Feb. 28, 1997) (62 FR 9258) (issuer cannot accept at face value representations by investors regarding their residence). See also IPONET, supra note 31 (IPONET's activities were supervised by an entity that verified information provided to IPONET by people who filled out IPONET's on-line questionnaire. Information from the questionnaires was used to determine whether respondents qualified as accredited investors and therefore were eligible to obtain password to access password-protected Web pages where IPONET posted private offerings).

36 Securities Act Release No. 7314 (July 25, 1996) (61 FR 40044); Securities Act Release No. 7187 (July 10, 1995) (60 FR 35645).

37 See , e.g., Rule 135 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.135).

38 This, however, would not include bona fide research that complies with the Commission's safe harbor rules for research reports. See Rules 137-139 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.137 - 230.139). Cf. Exchange Act Rule 15a-6(a)(2) (17 CFR 240.15a-6(a)(2))(conditional exemption from U.S. broker-dealer registration for foreign broker-dealers that furnish research reports to “major institutional investors” as defined in the rule).

39 Section 7(d) of the Investment Company Act generally prohibits a foreign fund from using U.S. jurisdictional means to make a public offer of its securities in the United States or to U.S. persons, unless the fund receives an order from the Commission permitting it to register under the Investment Company Act. The Commission may issue such an order only if it finds that it is legally and practically feasible to enforce the provisions of the Investment Company Act effectively against the foreign fund, and that the issuance of the order is consistent with the public interest and the protection of investors. For purposes of Section V, references to offers and sales to U.S. persons include offers or sales in the United States. Similarly, references to offers or sales in the United States include offers or sales to U.S. persons.

40 In addition, a foreign fund also may use the Internet exclusively to conduct a private U.S. offer. This release does not address the ability of a foreign fund to conduct a private U.S. offer over the Internet, except to the extent that it is relevant to the foreign fund's ability to simultaneously conduct an offshore Internet offer. See infra note 45 and accompanying text. As discussed above in Section I, the statements made in this release do not alter the requirement that all offers and sales in the United States must be pursuant to registration under the U.S. securities laws or an applicable exemption.

41 The staff previously took the position that under certain circumstances a foreign fund that is conducting an offshore offer also may make a private U.S. offer in reliance on the exclusion from the definition of “investment company” in Section 3(c)(l) of the Investment Company Act consistent with the public offering prohibition contained in Section 7(d). See Staff no-action letter, Touche Remnant & Co. (available Aug. 27, 1984) (“Touche Remnant“). In Goodwin Procter, supra note 13, the staff similarly took the position that under certain circumstances a foreign fund that is conducting an offshore offer also may make a private U.S. offer in reliance on the exclusion from the definition of “investment company” in Section 3(c)(7) of the Investment Company Act consistent with the public offering prohibition contained in Section 7(d). The staff also has stated that if U.S. persons become shareholders of a foreign fund for reasons beyond the control of the fund or persons acting on its behalf, the fund would not be required to count those shareholders as U.S. persons for purposes of determining whether the fund may rely on the exception from the definition of “investment company” in Section 3(c)(l) of the Investment Company Act. See Staff no-action letter, Investment Funds Institute of Canada (available Mar. 4, 1996). The same position applies to foreign funds relying on Section 3(c)(7) of the Investment Company Act. See generally Goodwin Procter, supra note 13. We take the position that Touche Remnant is superseded to the extent that it is inconsistent with these positions.

42 See notes 28-32 supra and accompanying text.

43 Although Rule 135c by its terms applies only to Section 5 of the Securities Act, we would take a similar approach with respect to the type of information that a foreign fund may, if required by foreign law, provide on its Internet site about a U.S. private offer without violating the public offering prohibition contained in Section 7(d) of the Investment Company Act. See supra note 32 and accompanying text.

44 An adviser to a foreign fund conducting an offshore Internet offer that also sponsors a U.S.-registered investment company with the same investment objectives and policies as the foreign fund may provide information about, or direct the viewer to, the registered U.S. offer without the Internet offer being considered to be a public offer of the foreign fund's securities in the United States.

45 See Lamp Technologies, Inc. and IPONET, supra note 31. Prequalification and password-type procedures are intended to ensure that only persons eligible to privately purchase the securities can obtain access to a Web site used in connection with a private offer and that the dissemination of information through the Internet site does not constitute a “general solicitation” under Rule 502(c) of Regulation D under the Securities Act. In addition to the procedures discussed in Lamp Technologies, there may be other, equally effective procedures designed to restrict access to information on the Internet to those persons who are eligible to purchase securities in a private U.S. offer.

46 See Section 48(a) of the Investment Company Act.

47 See supra notes 34-35 and accompanying text.

48 See supra note 36 and accompanying text.

49 See Section III.D., supra .

50 Id.

51 Section 203(a) of the Advisers Act generally prohibits any investment adviser from using U.S. jurisdictional means in connection with its business as an investment adviser, unless the adviser is registered with the Commission, or is exempted or excluded from the requirement to register. Section 203(b)(3) of the Advisers Act provides for an exemption from registration for any adviser who during the course of the preceding twelve months has had fewer than fifteen clients and who neither holds itself out generally to the public as an investment adviser nor acts as an adviser to a U.S.-registered investment company or business development company. The staff has taken the position that foreign advisers are required to count only their U.S. clients for purposes of determining whether they are exempt from registration under Section 203(b)(3). See Protecting Investors: A Half Century of Investment Company Regulation , at 223 n.6 (1992); Staff no-action letter, Murray Johnstone Ltd. (available Oct. 7, 1994).

52 See Use of Electronic Media by Broker-Dealers, Transfer Agents, and Investment Advisers for Delivery of Information, Securities Act Release No. 7288 (May 9, 1996) at text accompanying n. 32. But see Lamp Technologies, Inc., supra note 31.

53 See supra note 21 and accompanying text.

54 See text following supra note 21.

55 Exchange Act Rule 15a-6(a)(l) (17 CFR 240.15a-6(a)(l)).

56 Because a securities firm's Web site itself typically is a solicitation, orders routed through the Web site would not be considered “unsolicited.“

57 Section 5 of the Exchange Act, 15 U.S.C. 78e.

58 Exchange Act Release No. 38672 (May 23, 1997).

59 This last step would preclude an exchange from relying on this release if it, for example, sets the terms under which exchange members provide Internet access to the exchange, or makes arrangements for U.S. persons to directly clear and settle trades conducted on the exchange through the Internet. Foreign exchanges that knowingly provide U.S. persons with access to their trading facilities through the Internet would not be able to rely on this interpretation, and may be required to register with the Commission.