No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

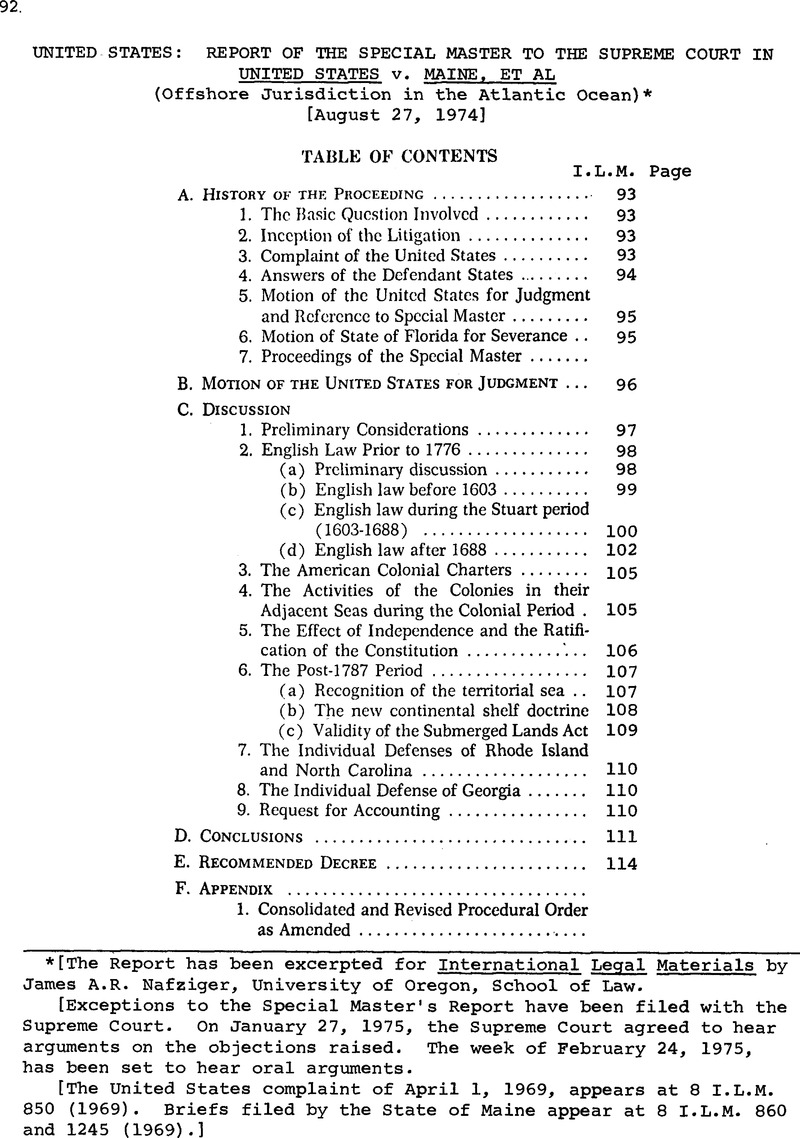

United States: Report of the Special Master to the Supreme Court in United States v. Maine, et al (Offshore Jurisdiction in the Atlantic Ocean)*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1975

Footnotes

[The Report has been excerpted for International Legal Materials by James A.R. Nafziger, University of Oregon, School of Law.

[Exceptions to the Special Master’s Report have been filed with the Supreme Court. On January 27, 1975, the Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments on the objections raised. The week of February 24, 1975, has been set to hear oral arguments.

[The United States complaint of April 1, 1969, appears at 8 I.L.M. 850 (1969). Briefs filed by the State of Maine appear at 8 I.L.M. 860 and 1245 (1969).]

References

* Camden, Annates (ed. 1635) 225 [quoted in Fulton, The Sovereignty of the Sea (1911) p. 107]. Bracton on the Laws and Customs of England, II Thorne ed. (1968), pp. 39-40.

† Fulton, The Sovereignty of the Sea (1911) p. 9. It is stated in Holdsworth, I History of English Law (3d ed. 1922) p. 550, that “after 1363 the Admiral’s criminal jurisdiction was recognized as exclusive on the high seas. This exclusive jurisdiction could be exercised over British subjects, over ‘ the crew of a British ship whether subjects or not, and over any one in cases of piracy at common law. It could be exercised over no other persons.”

* Fulton, The Sovereignty of the Sea (1911) p. 7.

* The treatise is set out in Moore, A History of the Foreshore and the Law Relatinq Thereto (1888) pp. 185 et seq. [Me. et al. Ex. 203].

* This claim to exclusive fishing rights was in direct opposition to the policy which had prevailed in the older English tradition of freedom for all nations to fish on the English coasts. Fulton, The Sovereignty of the Sea (1911) p. 57.

† Smith, The Law and Custom of the Sea (3d ed. 1959) p. 59; Brownlie, Principles of the Public International Law (1966) p. 208.

* Jones v. United States, 1890, 137 U.S. 202, 212; Fong Yue Ting v. United States, 1893, 149 U.S. 698, 707-711. And see The Paquete Habana, 1900, 175 U.S. 677, 700.

† Acceptance of the idea that the occupation of the sea by naval power could support a royal claim to ownership of the seabed was to be of short duration, however. Within a year after the end of the Stuart dynasty its demise was presaged by Sir Philip Medows, who in his Observations Concerning the Dominion and Sovereignty of the Seas (1689) [Me. et al. Ex. 202, p. 9] said: “To ride actual Master at Sea with a well Equipp’d Fleet, or to have such a Plenty of Naval Stores in constant readiness, as shall be sufficient to answer all Occasions, is not the Dominion of the Sea: This is Power, not Property,…”

* Thus it appears that even in Stuart times the situations in which claims of the crown to sovereignty of the sea were made normally involved only jurisdiction of the surface of the sea or control of the fisheries therein and not actual ownership of the seabed.

* Fulton, The Sovereignty of the Sea (1911) pp. 15, 18-21.

† And see Pitman B. Potter, The Freedom of the Seas in History, Law and Politics (1924) pp. 89-91.

* “The dominion of the land terminates where the power of arms ends.”

* Jessup, The Law of Territorial Waters and Maritime Jurisdiction (1927) p. 6.

† The first recognition by an English court of three miles as the limit of the marginal neutrality belt was by the eminent admiralty judge. Sir William Scott, afterward Lord Stowell, speaking for the High Court of Admiralty in 1800 in The Taee Gebroeders, 3 C. Rob. 162, 165 Eng. Repr. 422. In The “Anna”, 1805. 5 C. Rob. 373, 165 Eng. Repr. 809, a case in the same court involving the legality of the seizure of an American ship by an English privateer off the delta of the Mississippi River, Sir William Scott said [pp. 385b-385c]

“The capture was made, it seems, at the mouth of the River Mississippi, and, as it is contended in the claim, within the boundaries of the United States. We all know that the rule of law on this subject is ‘terrae dominium finitur, ubi finitur armorum vis,’ and since the introduction of fire-arms, that distance has usually been recognised to be about three miles from shore.”

See also Smith, The Law and Custom of the Sea (3d ed. 1959) p. 24.

* In Harris v. Owners of the Steamship Franconia, [1876-77] L.R. 2 Corn. Pl. Div. 173, three judges of the Common Pleas Division of the High Court, all of whom had dissented in The Queen v. Keyn, held themselves bound to apply the rule laid down by the majority in that case, the Chief Justice of the Division, Lord Coleridge, saying [p. 177]:

“… It seems to me to be quite plain that the decision in Reg. v. Keyn … is binding upon all the Courts. The ratio decidendi of that judgment is, that, for the purpose of jurisdiction (except where under special circumstances and in special Acts parliament has thought fit to extend it), the territory of England and the sovereignty of the Queen stops at low-water mark.”

* Massachusetts 1859 (Stat. 1859, ch. 289, as amended, Mass. Gen. Laws Ann. ch. 1, § 3); Rhode Island 1872 (R.I. Gen. Stat. 1872, Tit. I, ch. 1, § 1); New Hampshire 1901 (N. H. Laws 1901, c. 115); New Jersey 1906 (N. J. Stat. Ann. Tit. 40, § 18-5); Georgia 1916 (Acts 1916, p. 29, Ga. Code Ann. § 15-101). See United States v. Louisiana. 1960, 363 U.S. 1, 21 fn. 22. See also North Carolina 1947 Sess. L, c. 1031, N. C. Gen. Stat. § 141-6.