No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

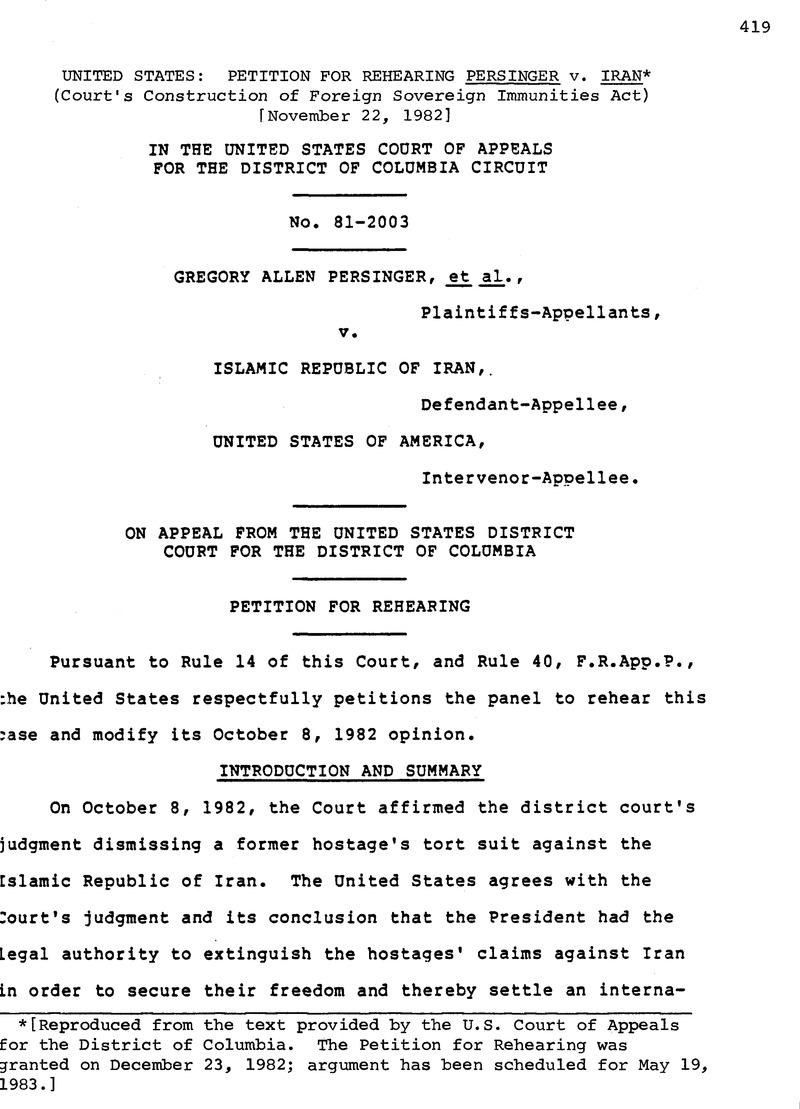

United States: Petition for Rehearing Persinger v. Iran (Court's Construction of Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act)*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1983

Footnotes

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. The Petition for Rehearing was granted on December 23, 1982; argument has been scheduled for May 19, 1983.]

References

1 Cf. Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398, 415,n.17 (1976) (act of state normally bars U.S. courts fromadjudicating the legality of foreign sovereign's acts under theirown law).

2 See also Meredith v. United States, 330 F.2d 9, 11 (9th Cir.1964); Restatement (2d) of the Foreign Felations Law of theUnited States, §38 (1965).

3 The principal motivation for the abrogation of a foreign state's immunity in tort cases was to preclude the immunity of aforeign state for traffic accidents or other tortious actions byforeign embassy officials in performing normal activities in thiscountry. H.R. Rep. No. 94-1487, supra, at 7, 20, 21 (1976).

4 See Restatement (2d) Foreign Relations Law of the United States, §69 (1965) (“The immunity of a foreign state * * * doesnot apply to a proceeding arising out of commercial activityoutside its territory.” (emphasis added)).

5 The fundamental precedent for sovereign immunity, TheSchooner Exchange v. McFaddon, 11 U.S. (7 Cranch) 116 (1812),itself distinguished between a sovereign's acts within its ownterritory for which it was absolutely immune, and acts outsideits own territory for which its immunity might be abrogated.

6 See, e.g. European Convention on State Immunity, Articles 6,7, 11, Council of Europe, No. 74 (1972)(“A Contracting Statecannot claim immunity * * * [in a tort case], if the facts whichoccasioned the injury or damage occurred in the territory of theState of the forum * * *.” Id; Art 11); State Immunity Act, Can.Stat. 29-30-31 Eliz. 2 c. 95, S6 [Canada] (1982); State ImmunityAct of 1978, 1978, c. 33, S5 [U.K.]; Foreign Sovereign ImmunityAct, 1981, SSMiii)r 6 [South Africa], see generally Materials onJurisdictional Immunities of States and Their Property, U.N. Leg.Ser., ST/LEG/SER.B/20 (1982).

7 The statutory purpose and legislative history clearly showthat Congress intended the PSIA to be in accordance with internationallaw and believed that it would not violate the internationalobligations of the United States. See 28 U.S.C. 1602;H.R. Rep. No. 1487, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 7 (1976) (hereinafter“House Report“); S. Rep. No. 1310, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 20 (1976)(hereinafter “Senate Report“); 122 Cong. Rec. 33532 (1976) (statementby Rep. Danielson). Indeed, the State Department's LegalAdviser pointed out that “[t]he bill would codify the internationallaw principle of sovereign immunity.” Jurisdiction ofU.S. Courts in Suits Against Foreign States, Hearings on H.R.11315 Before the Submcomm. on Administrative Law and GovernmentalRelations of the House Comm. on the Judiciary, 94th Cong., 2dSess. 26 (1976) (statement of Monroe Leigh, Legal Adviser)(hereinafter “1976 House Hearings“). Similarly, Mr. Bruno Ristau,Chief of the Foreign Litigation Unit of the Civil Division,Department of Justice, and one of the principal authors of thebill, said that “[t]he bill * * * fully comports with existinginternational practice * * *.” Id. at 32.

8 See also, McCulloch v. Sociedad Nacional de Marineros,372 U.S. 10, 21-22 (1963) (need for “clear expression” ofcongressional intent for a statute to be construed contrary tointernational law); Benz v. Compania Naviera Hidalgo, 353 U.S.138, 147 (1957) (to exercise U.S.nsdition in a “delicatefield of international relations there must be present the affirmativeintention of the Congress clearly expressed“); Lauritzenv. Larsen, 345 U.S. 571, 576-579 (1953); Restatement of theForeign Relations Law of the United States, (Revised) §402(4)(Tent. Draft No. 2, 1981).

9 A non-territorial referent of the phrase “in the UnitedStates” would also be contrary to the sovereign immunity practiceof the United States in our network of nearly two dozen modernFriendship, Commerce and Navigation Treaties. The immunityprovisions of these treaties, including the Treaty of Amity,Economic Relations, and Consular Rights with Iran, 8 U.S.T. 899,T.I.A.S. 3853 (1957), require relevant contacts with UnitedStates territory (see, id., at Art. XI(4)). The treaties werewell-known to Congress when it enacted the PSIA, (see H. Rep. No94-1487, supra, at 17), and there is no evidence Congressintended to work a fundamental change through the FSIA byexpanding “in the United States” to include foreign territory.See also, Restatement (2d) of the Foreign Relations Law of theUnited States, §60.

10 Under the European Convention, n.5, supra, the Frenchgovernment would be subject to suit in West Germany, the statein whose territory the accident occurred.

11 Further, Article 41(1) of the Vienna Convention explicitlyrequires that diplomats “respect the laws and regulations of thereceiving State.” Article 31 of the Convention limits theformerly absolute immunity from suit enjoyed by diplomatic agents.Under the Convention, diplomats are subject to certain categoriesof civil suit within the receiving state.

12 The United States follows a similar rule. See Fatemi v.United States, 192 A.2d 525, 527 (D.C. Ct. App. 1963) (embassynon extra-territorial); United States v. Moore, Crim. Complaint No. 2363-68 (D.C. Ct. of Gen. Sess., July 2, 1968) (“For thepurpose of arresting individuals for crimes committed on thepremises of the Embassy, the Embassy premises are a part of theUnited States“). See also, 1975 Digest of U.S. Practice inInternational Law, 239-240 (1976); 1976 Digest, supra, at 187-188; 1978 Digest, supra, at 551-554, 573-576.European precedents have long rejected the fiction of extraterritoriality.See Barat c. Ministere Public; Gazette duPalais, 1948, reported in 15 Ann. Digest Pub. Int’l L. Cases,1948 case #102 (Civil Tribunal of the Seine declared void anAmerican citizen's adoption of a French child according toCalifornia law and in the U.S. embassy; held: U.S. embassy inParis is French territory, therefore French adoption proceduresgovern); Afghan Embassy Case, 1934, reported in 7 Ann. DigestPub. Intl L. Cases, 1934, case #166 p. 385 (Afghani prosecuted inGermany for murder of Afghan minister in embassy; German courtretained jurisdiction despite extradition request of Afghanistan;held: no extraterritoriality to defeat German jurisdiction);Status of Legation Buildings Case, 1930, 5 Ann. Digest Pub. Int’lL. Cases, 1929-1930, case #197 (German statute required that, tobe eligible for unemployment compensation, one must have beenemployed “in Germany” for a certain period of time; held:employee of German embassy in London ineligible because was notemployed “in Germany“).

13 State Department regulations subject the authority of UnitedStates personnel to conduct depositions or perform notorial acts:o the legality of those functions under the law of the receivingitate. 22 C.F.R. 92.5, 92.9(a), 92.55(c). Consular officials’:apacity to administer the affairs and property of U.S. nationalsrho have died abroad must be predicated on and in conformity with;reaty, local law or established local custom or usage. 7 Foreignaffairs Manual [P.A.M.] 444D. Children born to foreign nationalsit United States embassies abroad would not be entitled to claimf.S. nationality by birth. 8 U.S.C. 1401, 1408 (1976, Supp. 1981).lee also 8 Whiteman, supra, at 119-127 (1967). The United States!oes not recognize or permit the celebration or solemnization oflarriages in foreign embassies except in accordance with localaw. 7 Whiteman, supra, 139-140 (1970). Members of Unitedtates embassy employees' families may not be employed in theeceiving state if such employment would violate local law22 C.F.R. 10.735-206(c)), regardless of whether the employmentould be on or off embassy premises. Embassy personnel may notnvest in real estate (22 C.F.R. 10.735-206(b)(2)), may notngage in financial or stock transactions (22 C.F.R. 10.735-06(b)(3)), and may not engage in any form of currency speculation22 C.F.R. 10.735-206(a)(l)-(6) (1982).

14 Erdos might also be read as applying a form of state jurisdiction over its own nationals. See, e.g. Restatement (2d), supra, §30.