No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

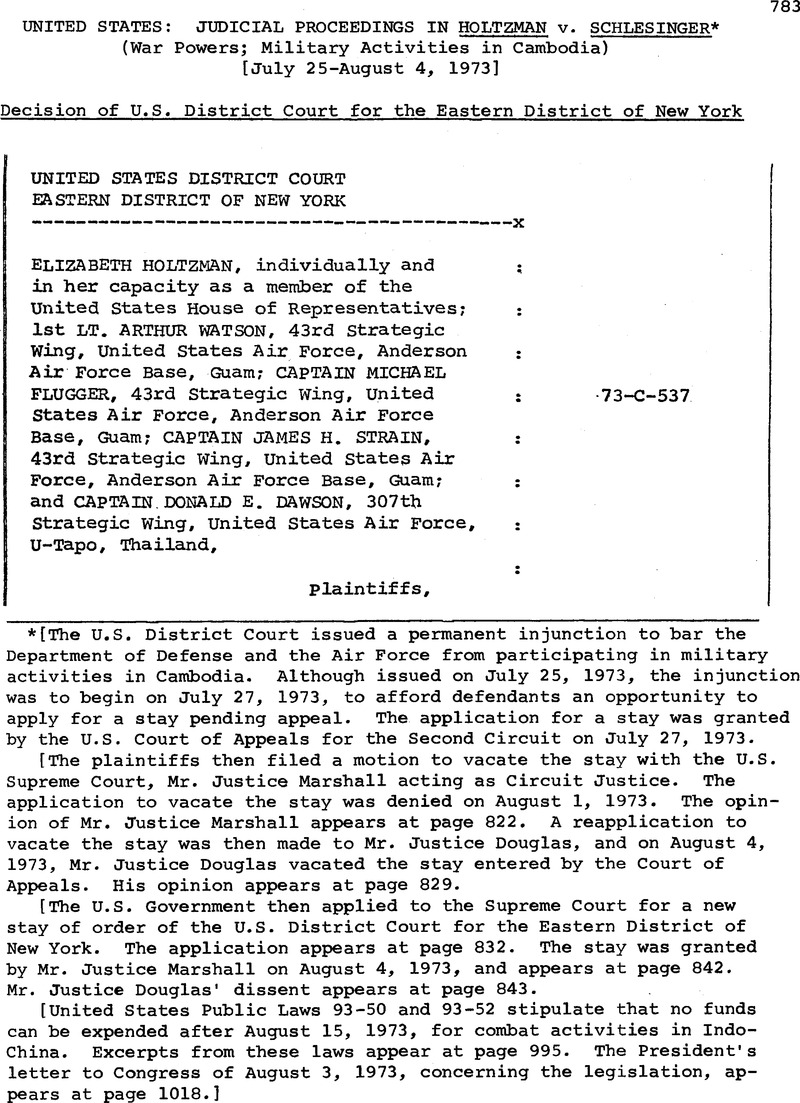

[The U.S. District Court issued a permanent injunction to bar the Department of Defense and the Air Force from participating in military activities in Cambodia. Although issued on July 25, 1973, the injunction was to begin on July 27, 1973, to afford defendants an opportunity to apply for a stay pending appeal. The application for a stay was granted by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit on July 27, 1973.

[The plaintiffs then filed a motion to vacate the stay with the U.S. Supreme Court, Mr. Justice Marshall acting as Circuit Justice. The application to vacate the stay was denied on August 1, 1973. The opinion of Mr. Justice Marshall appears at page 822. A reapplication to vacate the stay was then made to Mr. Justice Douglas, and on August 4, 1973, Mr. Justice Douglas vacated the stay entered by the Court of Appeals. His opinion appears at page 829.

[The U.S. Government then applied to the Supreme Court for a new stay of order of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York. The application appears at page 832. The stay was granted by Mr. Justice Marshall on August 4, 1973, and appears at page 842. Mr. Justice Douglas’ dissent appears at page 843.

[United States Public Laws 93-50 and 93-52 stipulate that no funds can be expended after August 15, 1973, for combat activities in Indo-china. Excerpts from these laws appear at page 995. The President’s letter to Congress of August 3, 1973, concerning the legislation, appears at page 1018.]

* [See I.L.M. page 787.]

1 Article I, § 8, cl. 11 provides: “The Congress shall have power . . . To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water.”

2 At the same time, the Court of Appeals ordered an expedited briefing schedule and directed that the appeal be heard on August 13. In the course of oral argument, on the stay, Acting Chief Judge Fein-berg noted that either side could submit a motion to further advance the date of argument. Counsel for petitioners indicated during argument before me that he intends to file such a motion promptly. Moreover, the Solicitor General has made representations that respondents will not oppose the motion and that, if it is granted, the case could be heard by the middle of next week. This case poses issues of the highest importance, and it is, of course, in the public interest that those issues be resolved as expeditiously as possible.

3 It appears, however, that covert American activity substantially predated the President’s April 30 announcement. See, e. g., of the New York Times. July 15. 1973. at 1. col. 1 (‘Cambodian Raids Re-ported Hidden before 70 Foray.”).

4 The Situation in Southeast Asia. 6 Presidential Documents 596, 598.

5 The Fulbright Proviso states:

‘‘Nothing [herein] shall be construed as authorizing the use of any such funds to support Vietnamese or other free world forces in actions designed to provide military support and assistance to the Government of Cambodia or Laos. 84 Stat. 910.

6 See 85 Stat. 423; 85 Stat. 716; 86 Stat. 734; 86 Stat. 1184.

7 84 Stat. 1943. See also 22 U. S. C. § 2416 (g).

8 The Eagleton amendment provided:

“None of the funds herein appropriated under this Act or heretofore appropriated under any other Act may be expended to support directly or indirectly combat activities in, over or from off the shores of Cambodia, or in or over Laos by United States forces.”

9 The President contemporaneously signed the Second Supple-mental Appropriations Act of 1973, Pub. L. 93-50, which contained a provision stating that

“[n]one of the funds herein appropriated under this Act may be expended to support directly or indirectly combat activities in or over Cambodia, Laos, North Vietnam and South Vietnam by United States forces, and after August 15, 1973, no other funds heretofore appropriated under any other Act may be expended for such purpose.”

10 While respondents offered to produce testimony at trial by high government officials as to the importance of the bombing, no affidavits by such officials alleging irreparable injury in conjunction with the stay application were offered.

11 For similar reasons, it would be a formidable task to judge where the public interest lies in this dispute, as courts traditionally do when determining the appropriateness of a stay. See, e. g., O’Brien v. Brown, 409 U. S. 1, 3 (1972).

12 I do not mean to suggest that this dispute will necessarily be moot after August 15. That is a question which is not now before me and upon which I express no views. Moreover, even if the August 15 fund cut-off does moot this controversy, petitioners may nonetheless be able to secure a Court of Appeals determination on-the merits before August 15. See n. 2, supra.

13 The Solicitor General vigorously argues that by directing that Cambodian operations cease on August 15, Congress implicitly authorized their continuation until that date. But while the issue is not wholly free from doubt, it seems relatively plain from the face-of the statute that Congress directed its attention solely to military actions after August 15, while expressing no view on the propriety of on-going operations prior to that date. This conclusion gains plausibility from the remarks of the sponsor of the provision— Senator Fulbright—on the Senate floor:

“The acceptance of an August 15 cut off date should in no way be interpreted as recognition by the committee of the President’s authority to engage U. S. forces in hostilities until that date. The-view of most members of the committee has been and continues to be that the President does not have such authority in the absence-of specific congressional approval.” 119 Cong. Rec. S. 12560 (Daily ed. June 29, 1973).

See also id., at S. 12562.

While it is true that some Senators declined to vote for the proposal because of their view that it did implicitly authorize continuation of the war until August 15, see id., at S. 12586 (Remarks of Sen. Eagleton); S. 12564 (remarks of Sen. Bayh); S. 12572 (remarks of Sen. Muskie), it is well established that speeches by opponents of legislation are entitled to relatively little weight in determining the meaning of the act in question.

* Sarnoff v. Schultz, 409 U. S. 929; DaCosta v. Laird, 405 U. S. 979; Massachusetts v. Laird, 400 U. S. 886; McArthur v. Clifford, 393 U. S. 1002; Hart v. United States, 391 U. S. 956; Holmes v. United States, 391 U. S. 936; Mora v. McNamara, 389 U. S. 934,. 935; Mitchell v. United States, 386 U. S. 972.

* [Reproduced from the text provided to International Legal Materials by the U.S. Department of Justice.

[The affidavit of William P. Rogers appears at page 838.]

[There is substantial authority that indicates that the President’s power as Commander-in-Chief authorizes him to conduct limited hostilities like those in Cambodia without Congressional authorization. Cf. Cross v. Harrison, 16 How. 164, 193; United States v. Curtis-Wright Corp., 299 U: S. 304, 315-316.

* [The dissent of Mr. Justice Douglas appears at page 843.]

1 The Court takes a bite out of the merits, for the order of Au-gust 4, 1973, bars the Court of Appeals from reinstating the judgment of the District Court until and unless this Court acts, as the order states that the order of the District Court “is hereby stayed pending further order by this Court.”

2 “The Supreme Court of the United States shall consist of a Chief Justice of the United States and eight associate justices, any six of whom shall constitute a quorum.” 28 U. S. C. § 1.

3 The statutes authorizing individual Justices of this Court to affirmatively grant applications for such actions do not authorize them to rescind affirmative action taken by another Justice. See, e. g., 28 U. S. C. § 2101 (f) (stays of mandate); 28 U. S. C. § 2241 (a) (writs of habeas corpus); 18 U. S. C. § 3141 and Fed. Rule Crim. Proc. 46 (a)(2) (granting of bail).

4 This requirement of collegial action is confirmed by the Rules of this Court and by this Court’s prior decisions and practices. Rules 50 and 51 govern the in chambers practices of the Court. Rule 50 (5) provides that, when one Justice denies an application made to him, the party who has made the unsuccessful application may renew it to any other Justice. It was pursuant to this Rule that application for the stay in this case was made to me. But neither Rule 50 nor Rule 51 authorizes a party, once a stay has been granted, to contest that action before another individual Justice.

The Court has <doubt together in Special Term before stays granted by an individual Justice out of Term could be overturned. In Rosenberg v. United States, 346 U. S. 273, the full Court felt constrained to consider its power to vacate a stay issued by an individual Justice, finally resting that power on the Court’s position—as a body—as final interpreter of the law:

“We turn next to a consideration of our power to decide, in this proceeding, the question preserved by the stay. It is true that the full Court has made no practice of vacating stays issued by single Justices, although it has entertained motions for such relief. But reference to this practice does not prove the nonexistence of the power; it only demonstrates that the circumstances must be unusual before the Court, in its discretion, will exercise its power.

“The power which we exercise in this case derives from this Court’s role as the final forum to render the ultimate answer to the question which was preserved by the stay.

“…[T]he reasons for refusing, as a matter of practice, to vacate stays issued by single Justices are obvious enough. Ordinarily the stays of individual Justices should stand until the grounds upon which they have issued can be reviewed through regular appellate processes.

“In this case, however, we deemed it proper and necessary to convene the Court to consider the Attorney General’s urgent application.” 346 U. S., at 286-287 (footnote omitted).

Finally, it is our procedure during a Term of Court to take an application that has already been denied or acted upon by one of the Justices to the entire Court upon an application made by the opposing side, so that the entire Court can act and thus prevent “shopping around.” That course is not possible during recess when the Justices are scattered around the country and throughout the world. There-fore it has been my practice if I grant a stay during recess to make that stay effective only until the Court convenes in October. This course could not be followed in the instant case because after August 15. 1973, the case will be moot.