No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

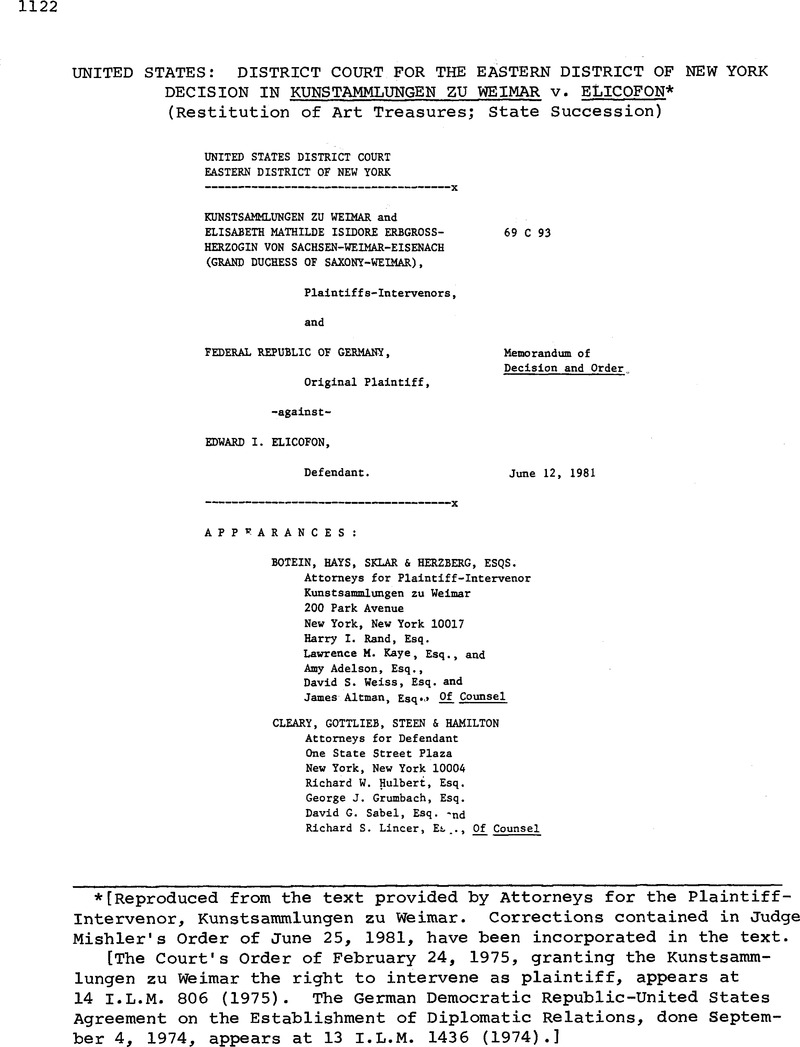

[Reproduced from the text provided by Attorneys for the Plaintiff- Intervenor, Kunstsammlungen zu Weimar. Corrections contained in Judge Mishler's Order of June 25, 1981, have been incorporated in the text.

[The Court's Order of February 24, 1975, granting the Kunstsammlungen zu Weimar the right to intervene as plaintiff, appears at 14 I.L.M. 806 (1975). The German Democratic Republic-United States Agreement on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations, done September 4, 1974, appears at 13 I.L.M. 1436 (1974).]

1 It was on the basis of the Settlement Agreement of 1927 that this court dismissed the intervenor complaint of the Grand Duchess of Saxony-Weimar, who had asserted ownership of the paintings by assignment from her former husband, Grand Duke Carl August. In our Memorandum of Decision dated August 24, 1978 we found that the terms of the Agreement absolutely foreclosed any claim of ownership by the Grand Dukes after 1927.

2 There is no doubt that deposition testimony may support a motion for summary judgment. Western Union Tel. Co. v. N.C.Direnzi, Inc., 441 F.Supp.l (E.D.Pa. 1977).

3 After the American Military assumed occupation of Thuringia, Thuringian admistrative bodies remained in existence and carried out their usual duties, but under the auspices of the Military Occupation authorities.

4 At the deposition of Dr. Scheidig this phrase, from the German “die beiden Duerer Portraits . . . konnten zunachest nicht gefunden werden,” was translated to mean that the Duerers could “for the time being not be found.” Elicofon claims that the translation given at the deposition was “a somewhat clumsy rendering” of the German phrase, which he claims should read “... could not be found at first.” Defendant’s Memorandum, p. 18 n.6. In view of Dr. Scheidig’s explanation of the phrase at his deposition, any dispute as to the exact translation of the phrase is irrelevant.

5 United States Army Records show that Russian troops replaced the Americans in “Landkreis Rudolstadt” at about midnight on July 2, 1945. (Sabel Afft. Exh. 1). The Thuringer Volkszeitung, a local newspaper, reported the entry of Russian troops into Gera, which is about 30 miles east of Weimar, also on July 2, 1945. By July 16, 1945, the Soviet political machinery was in place and had appointed a new President of Thuringia.

6 We reject Elicofon’s attempt to attach some significance to the variations in Dr. Scheidig’s accounts by suggesting that Dr. Scheidig changed his account of July 3 and July 5 to that of July 21 and thereafter in order to curry favor with the Russians. Elicofon would have us believe that Dr. Scheidig who for the purpose of suggesting such a motive Elicofon describes as a “bureaucrat by profession” was on July 3 and July 5, after the Russians had already marched into Thuringia, ignorant of the fact that the Russians were to assume power in Thuringia.

7 Unlike Elicofon, we find no significance in Dr. Scheidig’s statement that “the visit of 27th June had established the fact that the pictures were missing because of empty frames.” As Elicofon notes, this was the first time that Dr. Scheidig ever mentioned empty frames in connection with the June 27 visit. At all prior times, Dr. Scheidig stated that the paintings were missing from their racks in the storeroom on June 27. First, we note that Dr. Scheidig at the deposition, did not say that empty frames were lying about, like they were on July 19. Thus, he could well have been thinking of the empty space on the racks where the paintings had been located, which established that they were missing on June 27, and mistakenly said empty frames, since in the statement he was comparing his findings of June 27 with those of July 19.

8 Elicofon also notes that no member of Company F has ever been identified as a Princeton student despite Dr. Scheidig’s notation in his memorandum of June 15, 1945 that the American soldier who accompanied him to the depot after getting the keys from the commanding officer, was a Princeton student. Elicofon does not state in certain terms that no member of Company F was a Princeton student and does not indicate whether even if a soldier in Company F were a Princeton student what would be the likelihood of identifying him.

9 Even if ordinarily we would deny summary judgment simply to afford a jury or court an opportunity to view the demeanor of a witness whose credibility is challenged, such a justification does not exist in this case since Dr. Scheidig has already been cross-examined and has since died. E.g., Campbell v. American Fabrics Co., 168 F.2d 959 (2d Cir. 1948).

10 The issue of foreign law is a question of law. Fed.R.Civ.P. 44.1. In deciding an issue of foreign law a court may consider any relevant material or source. Kalmich v. Bruno, 553 F.2d 549 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 434 U.S.940, 98 S. Ct. 432 (1977).

On the issue of the German law doctrine of acquisition of title from a thief by a good faith purchaser, Elicofon submits the following affidavits:

Ernest C. Stiefel (1/80) §§ 12-18

Ernest C. Stiefel (6/80) §§ 9-36

The Kunstsammlungen submits the following affidavits:

Hans W. Baade (4/80) §§ 10-26

Hans W. Baade (7/80) §§ 3-14

Martin Posch (4/80) §§ 5-6

11 The Kunstsammlungen asserts that the phrase put in quotes by Dr. Scheidig “Bekummern” really means that Fassbender “concerned himself with” the artworks, and that by placing the word in quotations Dr. Scheidig meant to imply, in an ironic tone, that the person whose attitude is referred to in truth had no real concern for the matter, but merely pretended concern. In fact, in making the determination that Fassbender was a possessor of the paintings, Elicofon’s expert did not have the letter before him, but only had the translation given him by Elicofon. This Dr. Stiefel noted: “In determining the legal effect to be given to Dr. Scheidig’s words, it would be helpful if his original German statement could be examined.”

12 It is a well settled principle of international law that when a new government takes control over a territory, the law of the former sovereign remains in effect unless replaced by the new as “the law of the land.” Fremont v. united States. 58 U.S. (17 How.) 541, 536, 15 L.Ed. 241 (1855); United States v. Perot, 98 U.S. (8 Otto) 428, 25 L.Ed. 251 (1879); United States v. Chaves, 159 U.S. 452 (1895); See Whiteman, Digest of International Law 539. Thus, unless Military Law No. 52, legally promulgated, replaced the German law of bona fide acquisition by making all transfers of public property illegal, the German law of good faith acquisition would still have been in effect when Fassbender purportedly stole the paintings.

13 On the issue of Military Law No. 52, Elicofon submits the following affidavits:

Ernest Stiefel 6/80 § 38

Wolfgang Seiffert 6/80 §§ 3 to 10

The Kunstsammlungen submits the following affidavits:

Hans W. Baade 4/80 §§ 27 - 30

Hans W. Baade 7/80 §§ 19 - 21

Martin Posch 4/80 55 5 - 6

Bernard Graefrath 4/80 § 15

Manfred Hofmann 8/80 pg. 2-4 Exh. A-F

14 We reject Elicofon’s suggestion that Law No. 52 did not render the good faith acquisition of the paintings null and void but merely suspended the validity until the law went out of effect, at which time it was rendered retroactively valid. The rule cited by Elicofon applies only to executory contracts relating to the transfer of property subject to Law No. 52, but has no application to completed property transfers. This is because once the transfer has taken place there is no continuing intent to effect such a transfer and, therefore, nothing to be validated by the removal of the impediment.

15 Elicofon cites the case of Carl Zeiss Stiftung v. VEB Carl Zeiss Jena, 433 F.2d 686, 691 (2d Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 403 U.S. 905, 91 S. Ct. 2205 (1971) in support of his view that the U. S. Occupation authorities had no authority to promulgate Law No. 52. In that case, the Second Circuit questioned the authority of the united States Armed Forces to attempt on June 9, 1945 to set up a provincial government and appoint a Prime Minister of Thuringia when Thuringia had been allotted to Soviet occupation on Jun 5, 1945. We believe there is a monumental difference between the setting up of a provincial government in an area which has been allotted to occupation by another, on the one hand, and the issuing I of Military Orders for the maintenance of order and, specifically, the protection of public treasures in an area, on the other. The latter is a matter of necessity while the former may be viewed as an assertion of authority with a degree of permanence. We find the Second Circuit’s comments in Carl Zeiss regarding the provisional government to be wholly inapplicable to the issue presently before us.

16 The Notice of the Mayor was written in German. According to Elicofon the posting of Law No. 52 was required to be written in either English or French, and not in German. Even if this were the case we would regard the submission of the announcement of Law No. 52 in German as persuasive and uncontradicted evidence that Law No. 52 was indeed promulgated in Rudolstadt. In any event, Elicofon points to nothing in the text of the law to indicate that its promulgation was ineffective if issued in German.

17 See citations in footnote 12 of this opinion, supra.

18 We need not decide whether the applicable statute of limitations was that contained in Section 53 of the Civil Practice i Act for equity actions, i.e., ten years, or that contained in Section 49(4) of the Civil Practice Act for an action at law to recover a chattel, i.e., six years, since neither period I would have expired by 1949.

19 Prosser notes that New York’s courts take the minority view. Accord, Comment L to § 229 of the Second Restatement of Torts.

A demand and refusal are not necessary if the bona fide purchaser has sufficiently interfered with the owner’s right in some other way so as to constitute a conversion, for instance, where he sells the property, Pease v. Smith, 61 N.T. 477 (1875), or where he continues to possess the property as his own after learning that it was stolen, Employer’s Fire Ins, v. Cotten, 245 N.Y. 102, 156 N.E. 629 (1927).

20 Our discussion of the reasonableness of the delay in making the demand for the paintings also disposes of Elicofon’s assertion of the defense of laches, asserted in his answer as the Fifth I Affirmative Defense.

21 On the issue of succession of ownership of the Duerers, the Kunstsammlungen submits the following affidavits of experts:

Bernard Graefrath 4/80 § 4 - 29

Martin Posch 4/80 § 6(b)

Manfred Hofmann 9/80 pp. 5-8.

Elicofon submits the following affidavits of experts:

Wolfgang Seiffert 1/80 § 9 - 16

Wolfgang Seiffert 6/80 §§ 11 - 23

Ernest C. Steifel 1/80 § 20 - 22

22 Although the Federal Republic of Germany may regard itself as identical to the Reich government, notable international law theorists disagree and regard the Federal Republic rather as a legal successor to the Reich, reasoning as follows: Once a state becomes extinct under the international law, there can be no identity. In the case of Germany

the Occupying Powers took over the supremacy over all federal, state and local organs, so that all organs depended on them. All law in occupied Germany in 1945 after the unconditional surrender had its only reason of validity in the supremacy of the Occupying Powers. Even in 1954 there was still no sovereign Germany. . . . Under these conditions it seems impossible not to recognize that it ‘is clearly not identical with the Former German Reich. It is a new state . . . a successor state to the German Reich.’”

Kunz, Identity of States Under International Law, 49 Am.J. Int’l Law 68, 71 (1955), quoting Plischke, in Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 69 p. 262 (June, 1954).

23 In further support of the theory that it is the position of the German-Democratic Republic that the post-war Land of Thuringia acquired rights in property of the pre-war Land only by virtue of the Soviet sequestration and subsequent transfer of the property, Elicofon refers us to the charter of the Dresden Museum published on March 27, 1957 and the “Directive Concerning the Statute for the State Museum at Berlin dated January 25, 1952. Similar language is contained in both charters. The relevant portion of the Dresden charter reads:

The re-creation of the State Art Collections Dresden in the German Democratic Republic . . . was made possible by the generous act of friendship of the Government of the Soviet Union in transferring to the Government of the German Democratic Republic and thereby into the hands of the entire German people the treasures of the Dresden Art Gallery which were saved by the Soviet Army from destruction by Fascism.

24 Our discussion of this issue also disposes of Elicofon’s Sixth and Seventh affirmative defenses which, although not pressed in his motion for summary judgment, appear in his answer.

As his Sixth affirmative defense Elicofon asserts that by virtue of Law No. 47 of the Allied High Commission dated February 14, 1951, as amended, and the Convention on the Settlement of Matters Arising Out of the War and the Occupation, signed at Bonn, Germany, on May 26, 1952, as amended by Schedule IV to the Protocol on the Termination of the Occupation Regime in the Federal Republic of Germany, signed at Paris on October 23, 1954, the Kunstsammlungen zu Weimar may not maintain this action.

As a Seventh affirmative defense Elicofon asserts that the Kunstsammlungen zu Weimar should be barred from maintaining this action until such time as the German Democratic Republic of which it is an agency and instrumentality, agrees to recognize claims arising out of the criminal acts perpetrated by the government of Nazi Germany.

Our discussion of the principles of international law and our national policy which govern the Kunstsammlungen’s right to pursue this action precludes our considering the Sixth and Seventh affirmative defenses as barring plaintiff’s action.

25 On this issue Elicofon submits the following affidavits:

Wolfgang Seiffert 1/80 § 24 - 27

Wolfgang Seiffert 1/80 § 17

In support of its position on the issue of capacity to sue the Kunstsammlungen submits the following affidavits:

Bernard Graefrath 4/80 § 30 - 31

Martin Posch 4/80 § 13 - 14

Martin Posch 9/80

Manfred Hofmann 9/80 p. 4 - 5

26 We also reject Elicofon’s argument that the failure to publish the order of April 14 or the “statut” in the official gazette deprived the Kunstsammlungen of capacity. Elicofon offers no support that such publication is required or, moreover, even if required, that the failure to do so should defeat an action. Reason and fairness dictate the contrary.