Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

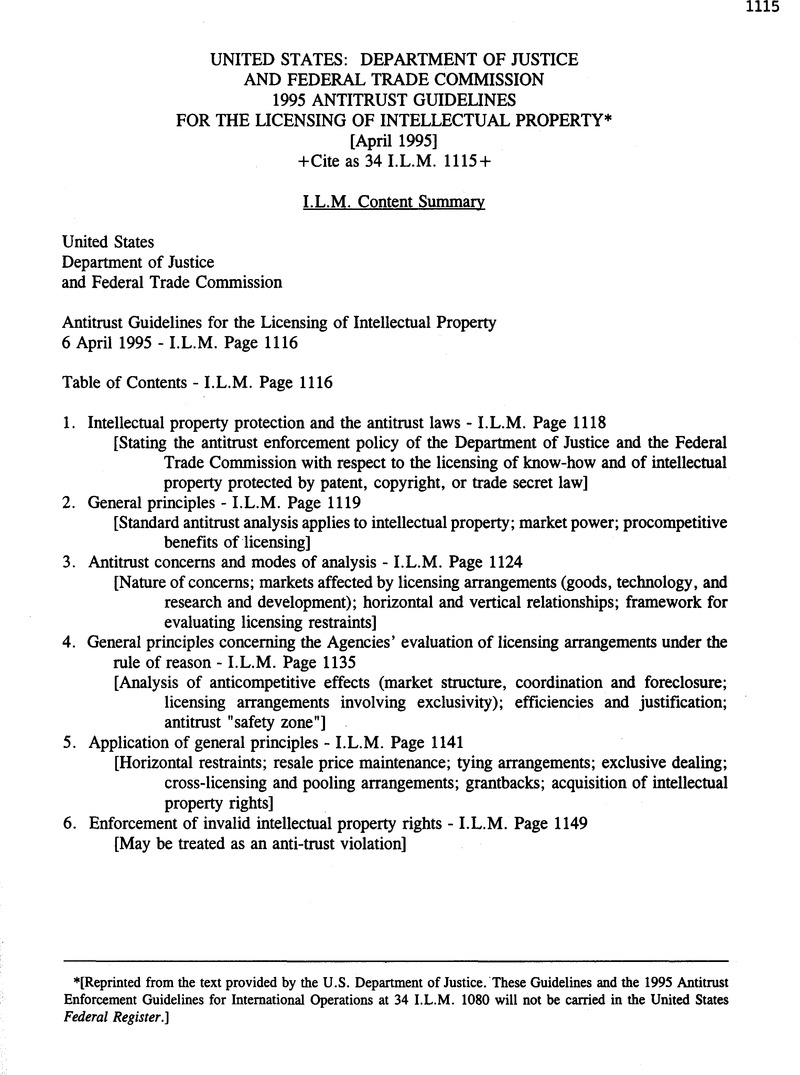

[Reprinted from the text provided by the U.S. Department of Justice. These Guidelines and the 1995 Antitrust Enforcement Guidelines for International Operations at 34 I.L.M. 1080 will not be carried in the United States Federal Register.]

1 These Guidelines do not cover the antitrust treatment of trademarks. Although the same general antitrust principles that apply to other forms of intellectual property apply to trademarks as well, these Guidelines deal with technology transfer and innovation-related issues that typically arise with respect to patents, copyrights, trade secrets, and know-how agreements, rather than with product-differentiation issues that typically arise with respect to trademarks.

2 As is the case with all guidelines, users should rely on qualified counsel to assist them in evaluating the antitrust risk associated with any contemplated transaction or activity. No set of guidelines can possibly indicate how the Agencies will assess the particular facts of every case. Parties who wish to know the Agencies’ specific enforcement intentions with respect to any particular transaction should consider seeking a Department of Justice business review letter pursuant to 28 C.F.R. § 50.6 or a Federal Trade Commission Advisory Opinion pursuant to 16 C.F.R. §§ 1.1-1.4.

3 See 35 U.S.C. § 154 (1988). Section 532(a) of the Uruguay Round Agreements Act, Pub. L. No. 103-465, 108 Stat. 4809 4983 (1994) would change the length of patent protection to a term beginning on the date at which the patent issues and ending twenty years from the date on which the application for the patent was filed.

4 See 17 U.S.C. § 102 (1988 & Supp. V 1993). Copyright protection lasts for the author's life plus 50 years, or 75 years from first publication (or 100 years from creation, whichever expires first) for works made for hire. See 17 U.S.C. § 302 (1988). The principles stated in these Guidelines also apply to protection of mask works fixed in a semiconductor chip product ﹛see 17 U.S.C. § 901 et seq. (1988)), which is analogous to copyright protection for works of authorship.

5 See 17 U.S.C. § 102(b) (1988).

6 Trade secret protection derives from state law. See generally Kewanee Oil Co. v. Bicron Corp., 416 U.S. 470 (1974).

7 “[T]he aims and objectives of patent and antitrust laws may seem, at first glance, wholly at odds. However, the two bodies of law are actually complementary, as both are aimed at encouraging innovation, industry and competition.” Atari Games Corp. v. Nintendo of America, Inc., 897 F.2d 1572, 1576 (Fed. Cir. 1990).

8 As with other forms of property, the power to exclude others from the use of intellectual property may vary substantially, depending on the nature of the property and its status under federal or state law. The greater or lesser legal power of an owner to exclude others is also taken into account by standard antitrust analysis.

9 Market power can be exercised in other economic dimensions, such as quality, service, and the development of new or improved goods and processes. It is assumed in this definition that all competitive dimensions are held constant except the ones in which market power is being exercised; that a seller is able to charge higher prices for a higher-quality product does not alone indicate market power. The definition in the text is stated in terms of a seller with market power. A buyer could also exercise market power (e.g., by maintaining the price below the competitive level, thereby depressing output).

10 The Agencies note that the law is unclear on this issue. Compare Jefferson Parish HospitalDistrict No. 2 v. Hyde, 466 U.S. 2, 16 (1984) (expressing the view in dictum that if a product is protected by a patent, “it is fair to presume that the inability to buy the product elsewhere gives the seller market power“) with id. at 37 n.7 (O'Connor, J., concurring) (“[A] patent holder has no market power in any relevant sense if there are close substitutes for the patented product.“). Compare also Abbott Laboratories v. Brennan, 952 F.2d 1346, 1354-55 (Fed. Cir. 1991) (no presumption of market power from intellectual property right), cert, denied, 112 S. Ct. 2993 (1992) with Digidyne Corp. v. Data General Corp., 734 F.2d 1336, 1341-42 (9th Cir. 1984) (requisite economic power is presumed from copyright), cert, denied, 473 U.S. 908 (1985).

11 United States v. Grinnell Corp., 384 U.S. 563, 571 (1966); see also United States v. Aluminum Co. of America, 148 F.2d 416, 430 (2d Cir. 1945) (Sherman Act is not violated by the attainment of market power solely through “superior skill, foresight and industry“).

12 The examples in these Guidelines are hypothetical and do not represent judgments about, or analysis of, any actual market circumstances of the named industries.

13 These Guidelines do not address the possible application of the antitrust laws of other countries to restraints such as territorial restrictions in international licensing arrangements.

14 A firm will be treated as a likely potential competitor if there is evidence that entry by that firm is reasonably probable in the absence of the licensing arrangement.

15 As used herein, “input” includes outlets for distribution and sales, as well as factors of production. See, e.g., sections 4.1.1 and 5.3-5.5 for further discussion of conditions under which foreclosing access to, or raising the price of, an input may harm competition in a relevant market.

16 Hereinafter, the term “goods” also includes services.

17 U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission, Horizontal Merger Guidelines (April 2, 1992) (hereinafter “1992 Horizontal Merger Guidelines“). As stated in section 1.41 of the 1992 Horizontal Merger Guidelines, market shares for goods markets “can be expressed either in dollar terms through measurement of sales, shipments, or production, or in physical terms through measurement of sales, shipments, production, capacity or reserves.“

18 For example, the owner of a process for producing a particular good may be constrained in its conduct with respect to that process not only by other processes for making that good, but also by other goods that compete with the downstream good and by the processes used to produce those other goods.

19 Intellectual property is often licensed, sold, or transferred as an integral part of a marketed good. An example is a patented product marketed with an implied license permitting its use. In such circumstances, there is no need for a separate analysis of technology markets to capture relevant competitive effects.

20 This is conceptually analogous to the analytical approach to goods markets under the 1992 Horizontal Merger Guidelines. Cf. § 1.11. Of course, market power also can be exercised in other dimensions, such as quality, and these dimensions also may be relevant to the definition and analysis of technology markets.

21 For example, technology may be licensed royalty-free in exchange for the right to use other technology, or it may be licensed as part of a package license.

22 The Agencies will regard two technologies as “comparably efficient” if they can be used to produce close substitutes at comparable costs.

23 E.g., Sensormatic, FTC Inv. No. 941-0126, 60 Fed. Reg. 5428 (accepted for comment Dec. 28, 1994); Wright Medical Technology, Inc., FTC Inv. No. 951-0015, 60 Fed. Reg. 460 (accepted for comment Dec. 8, 1994); American Home Products, FTC Inv. No. 941-0116, 59 Fed. Reg. 60,807 (accepted for comment Nov. 28, 1994); Roche Holdings Ltd., 113 F.T.C. 1086 (1990); United States v. Automobile Mfrs. Ass'n, 307 F. Supp. 617 (CD. Cal. 1969), appeal dismissed sub nom. City of New York v. United States, 397 U.S. 248 (1970), modified sub nom. United States v. Motor Vehicles Mfrs. Ass'n, 1982-83 Trade Cas. (CCH) \ 65,088 (CD. Cal. 1982).

24 See Complaint, United States v. General Motors Corp., Civ. No. 93-530 (D. Del., filed Nov. 16, 1993).

25 For example, the licensor of research and development may be constrained in its conduct not only by competing research and development efforts but also by other existing goods that would compete with the goods under development.

26 See, e.g., U.S, Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission, Statements of Enforcement Policy and Analytical Principles Relating to Health Care and Antitrust 20-23,37-40, 72-74 (September 27, 1994). This type of transaction may qualify for treatment under the National Cooperative Research and Production Act of 1993, 15 U.S.C.A §§ 4301-05.

27 Details about the Federal Trade Commission's approach are set forth in Massachusetts Board of Registration in Optometry, 110 F.T.C. 549, 604 (1988). In applying its truncated rule of reason inquiry, the FTC uses the analytical category of “inherently suspect” restraints to denote facially anticompetitive restraints that would always or almost always tend to decrease output or increase prices, but that may be relatively unfamiliar or may not fit neatly into traditional per se categories.

28 Under the FTC's Mass. Board approach, asserted efficiency justifications for inherently suspect restraints are examined to determine whether they are plausible and, if so, whether they are valid in the context of the market at issue. Mass. Board, 110 F.T.C. at 604.

29 The antitrust “safety zone” does not apply to restraints that are not in a licensing arrangement, or to restraints that are in a licensing arrangement but are unrelated to the use of the licensed intellectual property.

30 “Facially anticompetitive” refers to restraints that normally warrant per se treatment, as well as other restraints of a kind that would always or almost always tend to reduce output or increase prices. See section 3.4.

31 This is consistent with congressional intent in enacting the National Cooperative Research Act. See H.R. Conf. Rpt. No. 1044, 98th Cong., 2d Sess., 10, reprinted in 1984 U.S.C.C.A.N. 3105, 3134-35.

32 The conduct at issue may be the transaction giving rise to the restraint or the subsequent implementation of the restraint.

33 But cf. United States v. General Electric Co., 272 U.S. 476 (1926) (holding that an owner of a product patent may condition a license to manufacture the product on the fixing of the first sale price of the patented product). Subsequent lower court decisions have distinguished the GE decision in various contexts. See, e.g., Royal Indus, v. St. Regis Paper Co., 420 F.2d 449, 452 (9th Cir. 1969) (observing that GE involved a restriction by a patentee who also manufactured the patented product and leaving open the question whether a nonmanufacturing patentee may fix the price of the patented product); Newburgh Moire Co. v. Superior Moire Co., 237 F.2d 283, 293-94 (3rd Cir. 1956) (grant of multiple licenses each containing price restrictions does not come within the GE doctrine); Cummer-Graham Co. v. Straight Side Basket Corp., 142 F.2d 646, 647 (5th Cir.) (owner of an intellectual property right in a process to manufacture an unpatented product may not fix the sale price of that product), cert, denied, 323 U.S. 726 (1944); Barber- Coiman Co. v. National Tool Co., 136 F.2d 339, 343^4 (6th Cir. 1943) (same).

34 See, e.g., United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., 334 U.S. 131, 156-58 (1948) (copyrights); International Salt Co. v. United States, 332 U.S. 392 (1947) (patent and related product).

35 Cf. 35 U.S.C. § 271(d) (1988 & Supp. V 1993) (requirement of market power in patent misuse cases involving tying).

36 As is true throughout these Guidelines, the factors listed are those that guide the Agencies’ internal analysis in exercising their prosecutorial discretion.They are not intended to circumscribe how the Agencies will conduct the litigation of cases that they decide to bring.

37 The safety zone of section 4.3 does not apply to transfers of intellectual property such as those described in this section.