Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

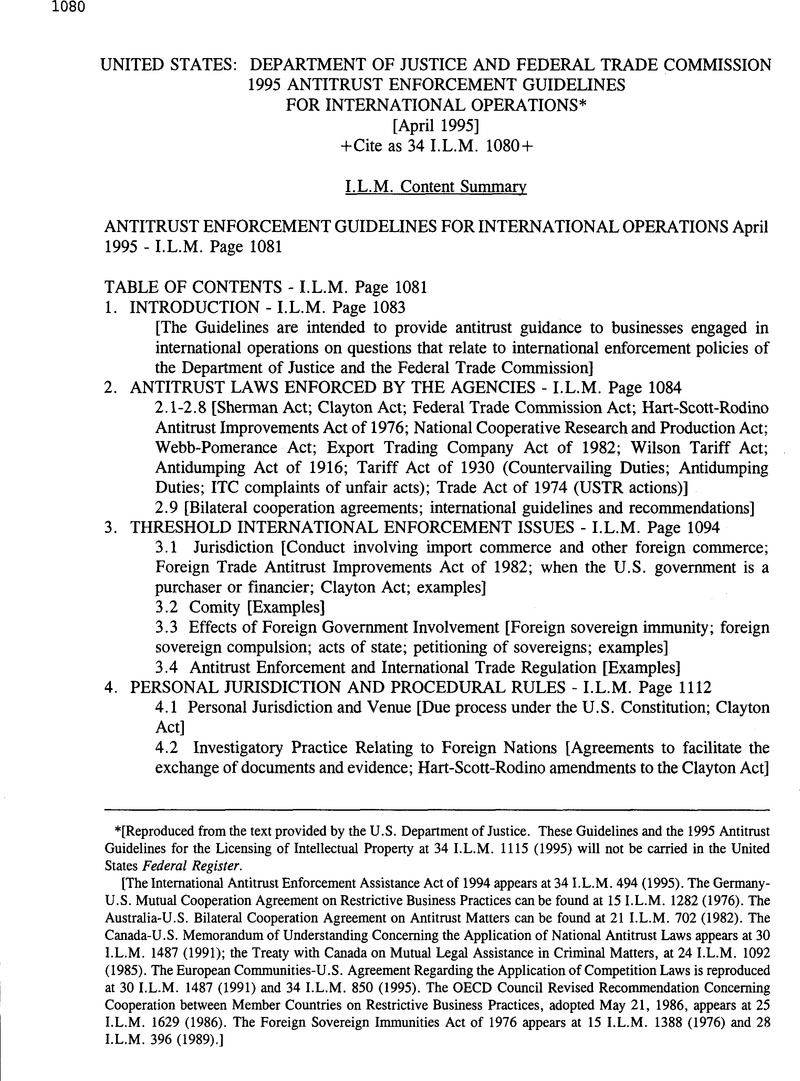

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Department of Justice. These Guidelines and the 1995 Antitrust Guidelines for the Licensing of Intellectual Property at 34 I.L.M. 1115 (1995) will not be carried in the United States Federal Register.

[The International Antitrust Enforcement Assistance Act of 1994 appears at 34 I.L.M. 494 (1995). The Germany- U.S. Mutual Cooperation Agreement on Restrictive Business Practices can be found at 15 I.L.M. 1282 (1976). The Australia-U.S. Bilateral Cooperation Agreement on Antitrust Matters can be found at 21 I.L.M. 702 (1982). The Canada-U.S. Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Application of National Antitrust Laws appears at 30 I.L.M. 1487 (1991); the Treaty with Canada on Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters, at 24 I.L.M. 1092 (1985). The European Communities-U.S. Agreement Regarding the Application of Competition Laws is reproduced at 30 I.L.M. 1487 (1991) and 34 I.L.M. 850 (1995). The OECD Council Revised Recommendation Concerning Cooperation between Member Countries on Restrictive Business Practices, adopted May 21, 1986, appears at 25 I.L.M. 1629 (1986). The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976 appears at 15 I.L.M. 1388 (1976) and 28 I.L.M. 396 (1989).]

1 The U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission Antitrust Guidelines for the Licensing of Intellectual Property (199S), the U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission Horizontal Merger Guidelines (1992), and the Statements of Antitrust Enforcement Policy and Analytical Principles Relating to Health Care and Antitrust, Jointly Issued by the U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission (1994), are not qualified, modified, or otherwise amended by the issuance of these Guidelines.

2 Readers should separately evaluate the risk of private litigation by competitors, consumers and suppliers, as well as die risk of enforcement by state prosecutors under state and federal antitrust laws.

3 28 C.F.R. § 50.6 (1994).

4 16C.F.R. §§ 1.1-1.4 (1994).

5 Defendants may be fined up to twice the gross pecuniary gain or loss caused by their offense in lieu of the Sherman Act fines, pursuant to 18 U.S.C. § 3571(d) (1988 & Supp. 1993). In addition, the U.S. Sentencing Commission Guidelines provide further information about possible criminal sanctions for individual antitrust defendants in § 2R1.1 and for organizational defendants in Chapter 8.

6 See 15 U.S.C. § 4 (1988) (injunctive relief); 15 U.S.C. § 15(a) (1988 & Supp. 1993) (damages).

7 See 15 U.S.C. §§ 16, 26 (1988).

8 Under the Clayton Act, “commerce” includes “trade or commerce among the several States and with foreign nations.“ “Persons” include corporations or associations existing under or authorized either by the laws of the United States or any of its states or territories, or by the laws of any foreign country. IS U.S.C. § 12 (1988 & Supp. 1993).

9 15 U.S.C. § 18 (1988). The asset acquisition clause applies to “person[s] subject to the jurisdiction of the Federal Trade Commission” under the Clayton Act.

10 15 U.S.C. § 14 (1988).

11 See, e.g., Mozart Co. v. Mercedes-Benz of N. Am., Inc., 833 F.2d 1342, 1352 (9th Cir. 1987), cert, denied, 488 U.S. 870 (1988).

12 15 U.S.C. §§ 13-13b, 21a (1988). The Robinson-Patman Act applies only to purchases involving commodities “for use, consumption, or resale within the United States.” Id. at § 13. It has been construed not to apply to sales for export See, e.g., General Chem., Inc. v. Exxon Chem. Co., 625 F.2d 1231, 1234 (5th Cir. 1980). Intervening domestic sales, however, would be subject to the Act. See Raul Infl Corp. v. Sealed Power Corp., 586 F. Supp. 349, 351-55 (D.N.J. 1984).

13 15 U.S.C. § 45 (1988 & Supp. 1993).

14 The scope of the Agencies’ jurisdiction under Clayton § 7 exceeds the scope of those transactions subject to the premerger notification requirements of the HSR Act. Whether or not the HSR Act premerger notification thresholds are satisfied, either Agency may request the parties to a merger affecting U.S. commerce to provide information voluntarily concerning the transaction. In addition, the Department may issue Civil Investigative Demands (“CIDs“) pursuant to the Antitrust Civil Process Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1311-1314 (1988), and the Commission may issue administrative CIDs pursuant to the Act of Aug. 26, 1994, Pub. L. No. 103-312, § 7; 108 Stat. 1691 (1994). The Commission may also issue administrative subpoenas and orders to file special reports under Sections 9 and 6(b) of the FTC Act, respectively. 15 U.S.C. §§ 49, 46(b) (1988). Authority in particular cases is allocated to either the Department or the Commission pursuant to a voluntary clearance protocol. See Antitrust & Trade Reg. Daily (BNA), Dec. 6, 1993, and U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission, Hart-Scott-Rodino Premerger Program Improvements (March 23, 1995).

15 Unless exempted pursuant to the HSR Act, the parties must provide premerger notification to the Agencies if (1) the acquiring person, or the person whose voting securities or assets are being acquired, is engaged in commerce or any activity affecting commerce; and (2Xa) any voting securities or assets of a person engaged in manufacturing which has annual net saies or total assets of $10 million or more are being acquired by any person which has total assets or annual net sales of SI00 million or more, or (b) any voting securities or assets of a person not engaged in manufacturing which has total assets of $10 million or more are being acquired by any person which has total assets or annual sales of $100 million or more; or (c) any voting securities or assets of a person with annual net sales or total assets of $100 million or more are being acquired by any person with total assets or annual net sales of $ 10 million or more; and (3) as a result of such acquisition, the acquiring person would hold (a) 15 percent or more of the voting securities or assets of the acquired person, or (b) an aggregate total amount of the voting securities and assets of the acquired person of $15 million. 15 U.S.C. § 18a(a) (1988). The size of the transaction test set forth in (3) must be read in conjunction with.C.F.R. § 802.20 (1994). This Section exempts asset acquisitions valued at $15 million or less. It also exempts voting securities acquisitions of $15 million or less unless, if as a result of the acquisition, the acquiring person would hold 50 percent or more of the voting securities of an issuer that has annual net sales or total assets of $25 million or more. The HSR rules are necessarily technical, contain other exemptions, and should be consulted, rather than relying on this summary.

16 16 15 U.S.C. § 18a(b) (1988 & Supp. 1993); 16 C.F.R. § 803.1 (1994); see also 11 U.S.C. § 363 (b)(2).

17 15 U.S.C. § 18a(e) (1988).

18 16 C.F.R. §§ 801-803 (1994).

19 16 C.F.R. §§ 801.l(e), (k), 802.50-52 (1994). See infra at Section 4.22.

20 See 16 C.F.R. § 803.30 (1994).

21 15 U.S.C. § 4302 (1988 & Supp. 1993).

22 See, e.g., U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission Antitrust Guidelines for the Licensing of Intellectual Property, § 4 (1995); Statements of Antitrust Enforcement Policy and Analytical Principles Relating to Health Care andAntitrust, Jointly Issued by the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission (1994), Statement 2 (outlininga four-step approach for joint venture analysis). See generally National Collegiate Athletic Ass'n v. Board of Regents of Univ. of Okla., 468 U.S. 85 (1984); Federal Trade Comm'n v. Indiana Fed'n of Dentists, 476 U.S. 447(1986). See also Massachusetts Board of Registration in Optometry, 110 F.T.C. 549 (1988).

23 Pub. L. No. 103-42, 107 Stat. 117, 119 (1993).

24 15 U.S.C. § 4306 (2) (Supp. 1993).

25 15 U.S.C. § 61 (1988).

26 See, e.g., Cases 89/85, etc., A. Ahlstrom Osakeyhtio v. Commission (“Wood Pulp“), 1988 E.C.R. 5193, [1987-1988 Transfer Binder] Common Mkt. Rep. (CCH) K 14,491 (1988).

27 See 12 U.S.C. §§ 372, 635 a-4, 1841, 1843 (1988 & Supp. 1993) (Because Title II does not implicate the antitrust laws, it is not discussed further in these Guidelines.)

28 15 U.S.C. §§ 4011-21 (1988 & Supp. 1993).

29 15 U.S.C. § 6a (1988); 15 U.S.C. § 45(a)(3) (1988).

30 15 U.S.C. § 4013(a) (1988).

31 H.R. Rep. No. 924, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 26 (1982). See 15 U.S.C. § 4021(6).

32 See 15 U.S.C. § 4016(b)(1) (1988) (injured party) and § 4016(bX4) (1988) (party against whom claim is brought).

33 15 U.S.C. § 4016(b)(5) (1988); see 15 U.S.C. § 25 (1988).

34 See Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration, Guidelines for the Issuance of Export Trade Certificates of Review (2d ed.), 50 Fed. Reg. 1786 (1985) (hereinafter “ETC Guidelines“).

35 U.S. Department of Commerce, International Trade Administration, The Export Trading Company Guidebook (1984).

36 15U.S.C. § 11(1988).

37 See 19 U.S.C. §§ 1671 et seq. (1988 & Supp. 1993), amended by Uruguay Round Agreements Act, Pub. L. No. 103-465, 108 Stat 4809 (1994).

38 Some alternative procedures exist under Tariff Act § 701(c) for countries mat have not subscribed to the World Trade Organization (“WTO“) Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures or measures equivalent to it. 19 U.S.C. § 1671(c) (1988 & Supp. 1993), amended by the Uruguay Round Agreements Act, Pub. L. No. 103-465, 108 Stat 4809 (1994).

39 See 19 U.S.C. §§ 1673 et seq. (1988).

40 19 U.S.C. § 1337 (1988), amended by the Uruguay Round Agreements Act, Pub. L. No. 103-465,108 Stat 4809 (1994).

41 19 U.S.C. §§ 1337(d), (f) (1988).

42 19 U.S.C. § 1337(bX2) (1988).

43 19 U.S.C. § 2412 (a), (b) (1988), amended by the Uruguay Round Agreements Act, Pub. L. No. 103-465, 108 Stat. 4805 (1994); see also Identification of Trade Expansion Priorities, Exec. Order No. 12,901, 59 Fed. Reg. 10,727 (1994).

44 19 U.S.C. § 2411(d)(3)(B)(i)(IV) (1988), amended by the Uruguay Round Agreements Act, Pub. L. No. 103-465, 10* Stat. 4809(1994), §314(c).

45 Chapter 15 of the North American Free Trade Agreement (“NAFTA“) addresses competition policy matters and commits the Parties to cooperate on antitrust matters. North American Free Trade Agreement Between the Government of the United States of America, the Government of Canada and the Government of the United Mexican States, 32 I.L.M. 605, 663 (1993), reprinted in H.R. Doc. No. 159, 103d Cong., 1st Sess. 712, 1170-1174 (1993).

46 Agreement Relating to Mutual Cooperation Regarding Restrictive Business Practices, June 23, 1976, U.S.-Federal Republic of Germany, 27 U.S.T. 1956, T.I.S. No. 8291, reprinted in 4 Trade Reg. Rep. (CCH) 13,501; Agreement Between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of Australia Relating to Cooperation on Antitrust Matters, June 29, 1982, U.S.-Australia, T.I.A.S. No. 10365, reprinted in 4 Trade Reg. Rep. (CCH) H 13,502; and Memorandum of Understanding as to Notification, Consultation, and Cooperation with Respect to the Application of National Antitrust Laws, March 9, 1984, U.S -Canada, reprinted in 4 Trade Reg. Rep. (CCH) 1) 13,503. The Agencies also signed a similar agreement with the Commission of the European Communities in 1991. See Agreement Between the Government of the United States of America and the Commission of the European Communities Regarding the Application of Their Competition Laws, Sept. 23, 1991, 30 I.L.M. 1491 (Nov. 1991), reprinted in 4 Trade Reg. Rep. (CCH) t 13,504. However, on August 9, 1994, the European Court of Justice ruled that the conclusion of the Agreement did not comply with institutional requirements of the law of the European Union (“EU“). Under the Court's decision, action by the EU Council of Ministers is necessary for this type of agreement. See French Republic v. Commission of European Communities (No. C-327/91) (Aug. 9, 1994).

47 Treaty with Canada on Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters, S. Treaty Doc. No. 28, 100th Cong., 2d Sess. (1988).

48 Pub. L. No. 103-438, 108 Stat. 4597 (1994).

49 See Revised Recommendation of the OECD Council Concerning Cooperation Between Member Countries on Restrictive Business Practices Affecting International Trade, OECD Doc. No. C(86)44 (Final) (May 21,1986). The Recommendation also calls for countries to consult with each other in appropriate situations, with the aim of promoting enforcement cooperation and minimizing differences that may arise.

50 The OECD has 25 member countries and the European Commission takes part in its work. The OECD's membership includes many of the most advanced market economies in the world. The OECD also has several observer nations, which have made rapid progress toward open market economies. The Agencies follow recommended OECD practices with respect to all member countries.

51 113 S. Ct. 2891, 2909 (1993). In a world in which economic transactions observe no boundaries, international recognition of the “effects doctrine” of jurisdiction has become more widespread. In the context of import trade, the “implementation” test adopted in the European Court of Justice usually produces the same outcome as the “effects” test employed in the United States. See Cases 89/85, etc., Ahlstrom v. Commission, supra at note 26. The merger laws of the European Union, Canada, Germany, France, Australia, and the Czech and Slovak Republics, among others, take a similar approach.

52 In re Massachusetts Bd. of Registration in Optometry, 110 F.T.C. 598, 609 (1988).

53 15 U.S.C. § 6a (1988) (Sherman Act) and § 45(a)(3) (1988) (FTC Act).

54 The examples incorporated into the text are intended solely to illustrate how the Agencies would apply the principles articulated in the Guidelines in differing fact situations. In each case, of course, the ultimate outcome of the analysis, i.e. whether or not a violation of the antitrust laws has occurred, would depend on the specific facts and circumstances of die case. These examples, therefore, do not address many of the factual and economic questions the Agencies would ask in analyzing particular conduct or transactions under the antitrust laws. Therefore, certain hypothetical situations presented here may, when fully analyzed, not violate any provision of the antitrust laws.

55 See infra at Section 3.12.

56 If the Sherman Act applies to such conduct only because of the operation of paragraph (1KB), then that Act shall apply to such conduct only for injury to export business in the United States. 15 U.S.C. § 6a (1988).

57 ee 15 U.S.C. § 45(aX3) (1988).

58 Summit Health, Ltd. v. Pinhas, 500 U.S. 322, 330-31 (1991).

59 If the Agencies lack jurisdiction under the FTAIA to challenge the cartel, the facts of this example would nonetheless lend themselves well to cooperative enforcement action among antitrust agencies. Virtually every country with an antitrust law prohibits horizontal cartels and the Agencies would willingly cooperate with foreign authorities taking direct action against the cartel in the countries where the agreement has raised the price of widgets to the extent such cooperation is allowed under U.S. law and any agreement executed pursuant to U.S. law with foreign agencies or governments.

60 Cf. Matsushita Elec. Indus. Co. v. Zenith Radio Corp., 475 U.S. S74 (1986).

61 Cf. Arizona v. Maricopa County Medical Soc'y, 457 U.S. 332 (1982); United States v. Socony-Vacuum Oil Co., 310 U.S. 150 (1940); United States v. Trenton Potteries Co., 273 U.S. 392 (1927).

62 See U.S. Department of Justice Press Release dated April 3, 1992 (announcing enforcement policy that would permit the Department to challenge foreign business conduct that harms U.S. exports when the conduct would have violated U.S. antitrust laws if it occurred in the United States).

63 One would need to show more than indirect price effects resulting from legitimate export efforts to support an antitrust challenge. See ETC Guidelines, supra at note 34, 50 Fed. Reg. at 1791.

64 That E and F together have an overwhelmingly dominant share in Epsilon may or may not, depending on the market conditions for Q, satisfy the requirement of “substantial effect on U.S. exports” as required by the FTAIA. Foreclosure of exports to a single country, such as Epsilon, may satisfy the statutory threshold if that country's market accounts for a significant part of the export opportunities for U.S. firms.

65 Cf. United States v. Concentrated Phosphate Export Ass'n, 393 U.S. 199,208 (1968) (“[Although the fertilizer shipmen were consigned to Korea and although in most cases Korea formally let the contracts, American participation was ti overwhelmingly dominant feature. The burden of noncompetitive pricing fell, not on any foreign purchaser, but on th American taxpayer. The United States was, in essence, furnishing fertilizer to Korea…. The foreign elements in tb transaction were, by comparison, insignificant.“); United States v. Standard Tallow Corp., 1988-1 Trade Cas. (CCH) f 67,91 (S.D.N.Y. 1988) (consent decree) (barring suppliers from fixing prices or rigging bids for the sale of tallow financed in who] or in part through grants or loans by the U.S. Government); United States v. Anthracite Export Ass'n, 1970 Trade Cas. (CCY If 73,348 (M.D. Pa. 1970) (consent decree) (barring price-fixing, bid-rigging, and market allocation in Army foreign ai program).

66 See ETC Guidelines, supra at note 34, 50 Fed. Reg. at 1799-1800. The requisite U.S. Government involvement could include the actual purchase of goods by the U.S. Government for shipment abroad, a U.S. Government grant to a foreign government that is specifically earmarked for the transaction, or a U.S. Government loan specifically earmarked for th transaction mat is made on such generous terms that it amounts to a grant. U.S. Government interests would not be considere to be sufficiently implicated with respect to a transaction that is funded by an international agency, or a transaction in whic the foreign government received non-earmarked funds from the United States as part of a general government-to-government aid program.

67 Such conduct might also violate the False Claims Act, 31 U.S.C. §§ 3729-3733 (1988 & Supp. 1993).

68 If, however, local law does not provide adequate remedies, or the local authorities are not prepared to take action, the Department will weigh the comity factors, discussed infra at Section 3.2, and take such action as is appropriate.

69 Clayton Act § 1, 15 U.S.C. § 12 (1988).

70 See supra at Section 3.121.

71 Through concepts such as “positive comity,” one country's authorities may ask another country to take measures that address possible harm to competition in the requesting country's market.

72 Hilton v. Guyot, 159 U.S. 113, 164 (1895).

73 The Agencies have agreed to consider the legitimate interests of other nations in accordance with the recommendations of the OECD and various bilateral agreements, see supra at Section 2.9.

74 The first six of these factors are based on previous Department Guidelines. The seventh and eighth factors are derived from considerations in the U.S.-EC Antitrust Cooperation Agreement. See supra at note 46.

75 113S.CL 2891,2910.

76 Foreign policy concerns may also lead the United States not to prosecute a case. See, e.g., U.S. Department of JusticePress Release dated Nov. 19,1984 (announcing the termination, based on foreign policy concerns, of a grand jury investigation into passenger air travel between the United States and the United Kingdom).

77 United States v. Baker Hughes, Inc., 731 F. Supp. 3, 6 n.5 (D.D.C. 1990), affd, 908 F.2d 981 (D.C. Cir. 1990).

78 Like the Department, the Commission considers comity issues and consults with foreign antitrust authorities, but the Commission is not part of the Executive Branch.

79 See, e.g., Timberlane Lumber Co. v. Bank of America, 549 F.2d 597 (9th Cir. 1976).

80 Not every country has compulsory premerger notification, and the events triggering duties to notify vary from country to country.

81 Section 1603(b) of the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976 defines an “agency or instrumentality of a foreign state” to be any entity “(1) which is a separate legal person, corporate or otherwise; and (2) which is an organ of a foreign state or political subdivision thereof, or a majority of whose shares or other ownership interest is owned by a foreign state or political subdivision thereof; and (3) which is neither a citizen of a State of the United States as defined in Section 1332(c) and (d) of [Title 28, U.S. Code], nor created under the laws of any third country.” 28 U.S.C. § 1603(b) (1988). It is not uncommon in antitrust cases to see state-owned enterprises meeting this definition.

82 28 U.S.C. §§ 1602, et seq. (1988).

83 28 U.S.C. § 1604 (1988 & Supp. 1993).

84 28 U.S.C. § 1605(aXl-6) (1988).

85 28 U.S.C. § 1605(aX2) (1988).

86 28 U.S.C. § 1603(d) (1988).

87 See, e.g., Republic of Argentina v. Weltover, Inc., 112 S. Ct. 2160 (1992); Schoenberg v. Exportadora de Sal, S.A. de C.V., 930 F.2d 777 (9th Cir. 1991); Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke's Medical Ctr. v. Hellenic Republic, 877 F.2d 574, 578 n.4 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 493 U.S. 937 (1989).

88 See, e.g., Saudi Arabia v. Nelson, 113 S. Ct. 1471 (1993); de Sanchez v. Banco Central de Nicaragua, 770 F.2d 1385 (5th Cir. 1985); Letelier v. Republic of Chile, 748 F.2d 790, 797-98 (2d Cir. 1984), cert, denied, 471 U.S. 1125 (1985); International Ass'n of Machinists & Aerospace Workers v. Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, 477 F. Supp. 553 (CD. Cal. 1979), affd on other grounds, 649 F.2d 1354 (9th Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 454 U.S. 1163 (1982).

89 28 U.S.C. § 1603(e) (1988).

90 See H.R. Rep. No. 1487, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 18-19 (1976), reprinted in 1976 U.S.C.C.A.N. 6604, 6617-18 (providing as an example the wrongful termination in the United States of an employee of a foreign state employed in connection with commercial activity in a third country.) But see Filus v. LOT Polish Airlines, 907 F.2d 1328, 1333 (2d Cir. 1990) (holding as too attenuated the failure to warn of a defective product sold outside of the United States in connection with an accident outside the United States.)

91 Republic of Argentina, 112 S. Ct. at 2168. This test is similar to proximate cause formulations adopted by other courts. See Martin v. Republic of South Africa, 836 F.2d 91,95 (2d Cir. 1987) (a direct effect is one with no intervening element which flows in a straight line without deviation or interruption), quoting Upton v. Empire of Iran, 459 F. Supp. 264, 266 (D.D.C. 1978), affd mem., 607 F.2d 494 (D.C. Cir. 1979).

92 Conduct by private entities not required by law is entirely outside of the protections afforded by this defense. See Continental Ore Co. v. Union Carbide & Carbon Corp., 370 U.S. 690,706 (1962); United States v. Watchmakers of Switzerland Info. Ctr., Inc., 1963 Trade Cas. (CCH) 170,600 at 77,456-57 (S.D.N.Y. 1962) (“[T]he fact that the Swiss Government may, as a practical matter, approve the effects of this private activity cannot convert what is essentially a vulnerable private conspiracy.into an unassailable system resulting from a foreign government mandate.“) See supra at Section 3.2.

93 Interamerican Refining Corp. v. Texaco Maracaibo, Inc., 307 F. Supp. 1291 (D. Del. 1970) (defendant, having been ordered by the government of Venezuela not to sell oil to a particular refiner out of favor with the current political regime, held not subject to antitrust liability under the Sherman Act for an illegal group boycott). The defense of foreign sovereign compulsion is distinguished from the federalism-based state action doctrine. The state action doctrine applies not just to the actions of states and their subdivisions, but also to private anticompetitive conduct that is both undertaken pursuant to clearly articulated state policies, and is actively supervised by the state. See Federal Trade Comm'n v. Ticor Title Insurance Co., 112 S. Ct. 2169 (1992); California Retail Liquor Dealers Ass'n v. Midcal Aluminum, Inc., 445 U.S. 97,105 (1980); Parker v. Brown, 317 U.S. 341 (1943).

94 For example, the Agencies may not regard as dispositive a statement that is ambiguous or that on its face appears to be internally inconsistent. The Agencies may inquire into the circumstances underlying the statement and they may also request further information if the source of the power to compel is unclear.

95 See Linseman v. World Hockey Ass'n, 439 F. Supp. 1315, 1325 (D. Conn. 1977).

96 As in all such cases, the Agencies would consider comity factors as part of their analysis. See supra at Section 3.2.

97 Banco National de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398, 421-22 n.21 (1964) (noting that other countries do not adhere in any formulaic way to an act of state doctrine).

98 See W.S. Kirkpatrick & Co. v. Environmental Tectonics Corp., 493 U.S. 400 (1990).

99 International Ass'n of Machinists and Aerospace Workers v. Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, 649 F.2d 1354, 1358 (9th Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 454 U.S. 1163 (1982).

100 See Timberlane, supra at note 79, 549 F.2d at 606-08.

101 Kirkpatrick, 493 U.S. at 405, quoting Ricaud v. American Metal Co., 246 U.S. 304, 310 (1918).

102 See Eastern R.R. Presidents Conference v. Noerr Motor Freight, Inc., 365 U.S. 127 (1961); United Mine Workers of Am. v. Pennington, 381 U.S. 657 (1965); California Motor Transp. Co. v. Trucking Unlimited, 404 U.S. 508 (1972) (extending protection to petitioning before “all departments of Government,” including the courts); Professional Real Estate Investors, Inc. v. Columbia Pictures Indus., 113 S. Ct. 1920 (1993). However, this immunity has never applied to “sham” activities, in which petitioning “ostensibly directed toward influencing governmental action, is a mere sham to cover … an attempt to interfere directly with the business relationships of a competitor.” Professional Real Estate Investors, 113S. Ct. at 1926, quoting Noerr, 365 U.S. at 144. See also USS-Posco Indus, v. Contra Costa Cty. Bldg. Constr. Council, AFL-CIO, 31 F.3d 800 (9th Cir. 1994).

103 See, e.g., Letter from Charles F. Rule, Acting Assistant Attorney General, Antitrust Division, Department of Justice, to Mr. Makoto Kuroda, Vice-Minister for International Affairs, Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry, July 30. 1986 (concluding that a suspension agreement did not violate U.S. antitrust laws on the basis of factual representations that the agreement applied only to products under investigation, that it did not require pricing above levels needed to eliminate sales below foreign market value, and that assigning weighted-average foreign market values to exporters who were not respondents in the investigation was necessary to achieve the purpose of the antidumping law).

104 Cf. United States v. Socony-Vacuum Oil Co., 310 U.S. 150, 226 (1940) (“Though employees of the government may have known of those programs and winked at them or tacitly approved them, no immunity would have thereby been obtained. For Congress had specified the precise manner and method of securing immunity [in the National Industrial Recovery Act]. None other would suffice…”):see also Otter Tail Power Co. v. United States, 410 U.S. 366, 378-79 (1973).

105 See also International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U.S. 310 (1945); Asahi Metal Industry Co. Ltd. v. Superior Court, 480 U.S. 102 (1987).

106 Go-Video, Inc. v. Akai Elec. Co., Ltd., 885 F.2d 1406,1414 (9th Cir. 1989); Wells Fargo & Co. v. Wells Fargo Express Co., 556 F.2d 406, 418 (9th Cir. 1977). To establish jurisdiction, parties must also be served in accordance with the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure or other relevant authority. Fed. R. Civ. P. 4(k); 15 U.S.C. §§ 22, 44.

107 See, e.g., Letter from Donald S. Clark, Secretary of the Federal Trade Commission, to Caswell O. Hobbs, Esq., Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, Jan. 17, 1990 (Re: Petition to Quash Subpoena Nippon Sheet Glass, et al, File No. 891-0088, at page 3) (“The Commission … may exercise jurisdiction over and serve process on, a foreign entity that has a related company in the United States acting as its agent or alter ego.“); see also Fed. R. Civ. P. 4; Volkswagenwerk AG v. Schlunk, 486 U.S. 694,707-708 (1988); United States v. Scophony Corp., 333 U.S. 795, 810-818 (1948).

108 For example, 28 U.S.C. § 1783(a) (1988) authorizes a U.S. court to order the issuance of a subpoena “requiring the appearance as a witness before it, or before a person or body designated by it, of a national or resident of the United States who is in a foreign country, or requiring the production of a specified document or other thing by him,” under circumstances spelled out in the statute.

109 See Societe Internationale pour Participations Industrielles et Commerciales, S.A. v. Rogers, 357 U.S. 197 (1958).

110 International Antitrust Enforcement Assistance Act of 1994, Pub. L. No. 103-438, 108 Stat. 4597 (1994).

111 See 16 C.F.R. §§ 802.50-52 (1994).

112 See 16 C.F.R. § 802.50(a) (1994).

113 See 16 C.F.R. § 802.50(b) (1994).

114 See 16 C.F.R. § 802.51 (1994).

115 See 16 C.F.R. § 802.52 (1994).