No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

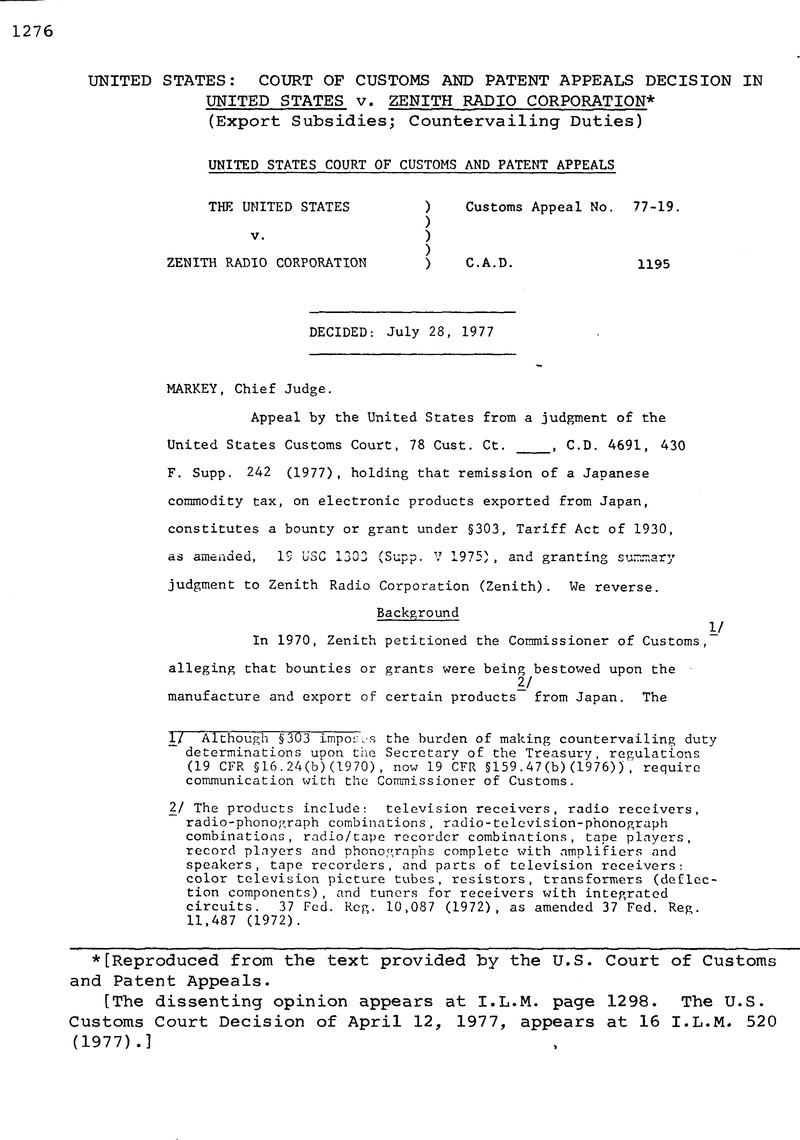

United States: Court of Customs and Patent Appeals Decision in United States v. Zenith Radio Corporation*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1977

Footnotes

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Court of Customs and Patent Appeals.

[This report is basically a status report on the provisional draft articles on State responsibility, on succession of States in respect of matters other than treaties, and on treaties concluded between States and international organizations or between international organizations. The material that appears in brackets did not elicit consensus and will be given further consideration.]

References

1 Although §303 imposes the burden of making countervailing duty determinations upon the Secretary of the Treasury, regulations (19 CFR §16.24(b)(1970), now 19 CFR §159.47(b) (1976)), require communication with the Commissioner of Customs.

2 The products include: television receivers, radio receivers, radio-phonograph combinations, radio-television-phonograph combinations, radio/tape recorder combinations, tape players, record players and phonographs complete with amplifiers and speakers, tape recorders, and parts of television receivers: color television picture tubes, resistors, transformers (deflection components), and tuners for receivers with integrated circuits. 37 Fed. Reg. 10,087 (1972), as amended 37 Fed. Reg. 11,487 (1972).

3 Tax exemption is also accorded certain goods sold at home to educational and welfare institutions, the National Museum, and other specified purchasers.

4 We employ “remission” to denote both tax exemption and tax refund, which are legally indistinct on this appeal.

5 A tax on American exports would be unconstitutional. U.S. Const, art. 1, §9, cl. 5. Fairbank v. United States, 181 U.S. 283 (1901). Amicus cites the remission of state taxes upon shipments into other states of the United States. Neither consideration is applicable to a determination under §303.

6 Judge Richardson wrote for the court. Judges Newman and Boe filed concurring opinions. The thorough treatment given the issues by the distinguished judges of the panel rests essentially upon an interpretation of Downs with which we differ.

7 The parties have described the tax as a “commodity,” “consumption,” and “excise” tax. For clarity, we employ “excise” throughout.

8 The United States contends on appeal that under §516(g), 19 USC 1516(g) (Supp. V 1975), the Customs Court exceeded its subject matter jurisdiction in ordering duties imposed prior to publication of the decision in the Customs Bulletin. We do not reach that issue.

9 Post Downs, the world has seen two World Wars, an industrial revolution, a scientific revolution, and flight from Kitty Hawk to the moon. Customs duties, though large, are not our sole source of government funds, as they virtually were prior to 1916. If, nonetheless, the Supreme Court had established the law in 1903, mere passage of years could not effect our decision, the duty of revising laws to fit a new world having been constitutionally assigned to the Congress.

10 The Tariff Act of 1922, ch. 356, §303, 42 Stat. 935, broadened the countervailing duty law to include bounties or grants paid on manufacture and production.

11 The language has been described as dicta by some commentators, e.g., Butler, Countervailing Duties and Export Subsidization: A Re-emerpJng “Issue in International Trade, 9 Va. J. Int’l L. 82 (1968-69); feller, Mutinv Against the Bounty: An Examination of Subsidies, Border Tax Adjustments, and the Resurgence of the Countervailing Duty Law, 1 Law & Pol, Int’l Bus. 17 (1969); Note, The Michelin Decision: A Possible New Direction for U.S. Countervailing Duty Law, 6 Law & Pol. Int’l Bus . 237 (1974), and by this court, In referring to the Customs Court’s reliance on Downs and Nicholas, infra, in United States v. Hammond Lead Products. Inc., 58 CCPA 129, 137, C.A.D. 1017, 440 F.2d 1024, 1030 (1971), cert. denied, 404 U.S. 1005 (1971).

12 A review of the cited and researched cases establishes, as in Downs, that the bounty or grant in each case was found to reside in, and was measured by, an excess over the remission of excise taxes. Nor is that surprising in view of Treasury’s practice, discussed infra. Thus, in Franklin Sugar Refining v. United States, 1 Ct. Cust. Appls. 242, T.D. 31276 (1911), a 2.50 mark “export bounty” was countervailed and a remitted 20 mark consumption tax was not. In Nicholas a British scheme involved tax remission and an “allowance” of 3d and 5d per gallon for exported spirits On appeal in American Express, supra, this court found it unnecessary to review the Customs Court’s broad interpretation of Downs and Nicholas and looked to the many hidden taxes which were remitted in excess of any remitted excise tax. United States v. Hills Bros. Co. 107 F. 107 (2d Cir. 1901) involved excess rebates on sugar exports. F. W. Woolworth Co. v. United States, 28 CCPA 239 (1940), involved a bounty created by currency manipulation. In Marion R. Gray v. United States, 70 Treas. Dec. 811, T.D. 48679 (1935), the Customs Court stated, “* * * at least a part of the excess of Great Britain’s drawback paid to the manufacturer, constitutes a bounty or grant * * * under section 303 of the tariff act involved.” [Emphasis added. Id. at 813]

United States v. Passavant, 169 U.S. 16 (1898), involved dutiable value? not countervailing duties. F. W. Meyers, supra, involved an export duty governed by para. 393, Tariff Act of 1897, not the remission of an excise tax.

13 Judicial review of negative countervailing duty determinations was not sought before 1971. Congress made it available to manufacturers, producers and wholesalers in 1975, §516(d), Tariff Act of 1930, as amended, 19 USC §1516(d) (Supp. V 1975), in response to this court’s recognition of its nonavailability to those groups in Hammond Lead, supra note 11.

Congress did not, however, require hearings and preparation of a hearing record from which it might be determined, on review, whether the Secretary’s action was supported by substantial evidence or was arbitrary or capricious, in the manner practiced, for example, under the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 USC 551 et seq. Nor have the regulations, 19 CFR 159.47, Part 175 (1976), prescribed under §516(h), done so. Congress did require hearings, on request, in antidumping cases, 19 USC 160(d) (Supp. V 1975).

14 The United States cites the exclusion of internal taxes remitted on exports from the cost of materials in determining constructed value, §402(d), Tariff Act of 1930, as amended, 19 USC 1401a(d), and the including of such remitted taxes in determining purchase price under §203, Antidumping Act of 1921, 19 USC 162 (Supp. V 1975), as indicating congressional evaluation of such remissions as neither unfair nor prohibitive. The point may be useful in urging consistency on the part of the Congress. It cannot, however, supply a congressional definition of “bounty,” “grant” or “net amount” appearing in §303.

15 Congress’ most recent reference to the international implications of export incentives and countervailing duties, and to the role of the Executive in connection herewith, appears in §331(a), Trade Act of 1974, 19 USC 1303(d)(1) (Supp. V. 1975):

It is the sense of the Congress that the President, to the extent practicable and consistent with United States interests, seek through negotiations the establishment of internationally agreed rules and procedures governing the use of subsidies (and other export incentives) and the application of countervailing duties.

To facilitate negotiations, Congress, while continuing to refrain from a definition of “bounty” or “grant,” granted authority to the Secretary to suspend during the four years beginning January 3, 1975, and under certain conditions, the imposition of countervailing duties, after having determined that a bounty or grand is in fact being bestowed, 19 USC 1303(d)(2), and to reinstate such duties, 19 USC 1303(d)(3). In §1303(e), Congress provided for reports to it of actions under §1303(d)(2), and for the undoing thereof upon a resolution of disapproval by the Senate or the House.

16 Notes on Tariff Revision (1908). The quoted paragraph appears on page 834 of the 953 page document. The portions on court interpretation were prepared by an assistant counsel of the Treasury.

17 United States Tariff Commission, Reciprocity and Commercial Treaties, 434 (1919) (available, Department of State Library).

18 See I Treas. Dec. 696, T.D. 19321 (1893); 2 Treas. Dec. 157, T.D. 19729 (1898); 2 Treas, Dec. 996, T.D. 20407 (1898); 26 Treas. Dec 825, T.D. 34466 (1914); 54 Treas. nec ?U, T.D. 42895 (1928); 56 Treas. Dec, 342, T.D. 43634 (1929); 73 Treas. Dec. 107, T.D. 49355 (1938). See also, the countervailing duty cases in note 12, supra.

19 Treasury’s administrative practice and some of its rationale was described to Congress in Executive Branch GATT Studies, S. Comm. on Finance, 93d Cong., 2d Sess. 11-12 (1974):

Under administrative precedents dating back to 1897, the Treasury Department has generally not construed the rebate, remission or exenrotion on exports of ordinary indirect taxes (consumption taxes on goods) to be a “bounty or grant” within the meaning of our countervailing duty statute * * * since exports are not consumed in the country of production, they should not be subject to consumption taxes in that country. * * * application of countervailing duties to the rebate of consumption taxes -would have the effect of double taxation * * * the United States would * * * impose * * * Federal and state excise taxes and state and local sales taxes, but would also collect, through * * * countervailing duty, the indirect tax imposed by the exporting country on domestically consumed goods.

The Treasury Department has not applied these precedents to tax “rebates” in excess of taxes collected on the exported product. If, for example, the foreign exporter has paid $1 in excise taxes on a product he exports to the United States but receives a rebate of $1,20 on exportation, under long established administrative precedents of the Treasury Department the imported merchandise would be subject to a countervailing duty of $0.20.

The Treasury Department has historically assumed that an excise tax is part of the price paid by home consumers. On the present record, that must be assumed true of the Japanese Commodity Tax. Where the tax is “paid” by home consumers, its remission on exports has not been considered a bounty or grant because the remission does not increase the manufacturer’s profit margin. In recent years, a dichotomy has grown among economists regarding the possible difference in result when all or part of the tax is either “forward-shifted” or “absorbed.” See the commentaries listed supra note 11, and Rosendahl, Border Tax Adjustments: Problems and Proposals, 2 Law Pol. Int’1 Bus. 85 (1970).

20 For example, in Copper Queen Mining Co. v. Territorial Board of Equalization, 206 U.S. 474, 479 (1907), the Court was faced with an 18-year-old administrative interpretation of the statute. Justice Holmes wrote: “[W]hen for a considerable time a statute notoriously has received a construction in practice from those whose duty it is to carry it out, and afterwards is reenacted in the same words, it may be presumed that the construction is satisfactory to the legislature, unless plainly erroneous, since otherwise naturally the words would have been changed.”

21 The United States cites the reasonableness of its practice and numerous cases setting forth guidelines for judicial review of agency action under the Administrative Procedure Act. We are not, however, reviewing a record under that Act in this case. See, supra note 13.

The United States also argues that its long practice coincides with international agreements (e.g., the GATT) and with international practice, that international trade would become a shambles, and that trade wars would erupt, if the Secretary were now required to find that mere remissions of excise taxes bestowed bounties. Such arguments are irrelevant here. No agency practice may, for any reason, repeal a statute or overrule the courts. If the practice were in conflict with the statute, the intent of Congress, or judicial precedent, it could not stand, and such arguments would have to be directed to the Congress, If no conflict or inconsistency exists, the arguments are unnecessary.

22 Extension of Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act, Hearings Before the Senate Comm. on Finance, 81st Cong., 1st Sess. , 1195-99 (1949) (memorandum).

23 See H.R. 8304 - 81st Cong., 2d Sess. (1951) and Hearings on H.R. 1535 Before the House Comm. on Ways and Means, 82d Cong., 1st Sess. , 2, 79 (1951). See Hearings on H.R. 5505 Before the Senate Comm. on Finance, 82d Cong,, 2d Sess., 115, 124-125 (1952).

In 1951, the State Department advised the Senate Finance Committee of the administrative practice under §303 and that an amendment specifically stating that practice would merely clarify the law and would effect no change in the practice followed since the original enactment in 1897. See Hearings on H.R. 1612 Before the Senate Comm. on Finance, 82nd Cong., 1st Sess., 1197 (1951).

24 See 2 Compendium of Papers on Legislative Oversight Review of U.S. Trade Policies, Comm. on Finance, QQth Cong., 2nd Sess. 475-476, 568-569, 887-889, 918-919 (1968).

25 See S. Finance Comm. Rep. No. 91-1481 [to accompany H.R. 17550], 91st Cong., 2nd Sess. 284-285 (1970).

26 The growing tendency of those who fail in their objective before the Congress to thereafter submit the same plea to undermanned federal courts is one factor contributing to the current appellate flood, which threatens to drown justice in the thrashings of a litigious sea. See Horowitz, D., The Courts and Social Policy 4–16 (The Brookings Institution, 1977)Google Scholar. Sadly, moreover, the crowd can jam the courthouse door against the more deserving and less-advantaged.

27 See Hearings on H.R. 6767 Before the House Comm. on Ways and Means, 93rd Cong., 1st Sess., 2169-2171, 2496-2500, 3097, 3292-3293, 3814-3815 (1973). The Senate Committee on Finance Subcommittee on International Trade was so advised in 1971. See Hearings on World Trade and Investment Issues Before the Sub-comm. on International Trade of the Senate Comm. on Finance, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 102, 109-111 (1971). Though Congress’ current interest in governmental assistance to foreign manufacturers may be assumed to have been occasioned by falling shares of the American market for American manufacturers, an abrupt change in a lone-standing practice may have been viewed as both counter-productive in a trading world of increasingly interdependent economies and as injurious to American consumers on whom the countervailing duty might fall in the form of increased prices. However that may be, it is sufficient to our present task that Congress did not make the requested change in Treasury’s practice.

28 H.R. Rep. No. 93-571, 93d Cong., 1st Sess. 69 (1973).

29 S. Rep. No. 93-1298, 93d Cong., 2d Sess. 172 (1974).

30 That the two key committees of the Congress, with Treasury’s treatment of the Japanese Commodity Tax law and the fact of Zenith’s objections before them, and with full investigative powers and resources available, could not either approve or disapprove the administrative practice on its merits, is a dramatic exemplification of the reasons why a court should avoid entry into that policy thicket. Under appropriate conditions, courts may, as we do here, hold that an administrative practice reflects a permissible interpretation of a statute, while neither approving or disapproving the merits of the practice. Approving or disapproving the wisdom, effectiveness, etc., of an agency practice is a function of the Congress, the shifting of which to the courts conflicts with the fundamental separation of powers doctrine.

31 The United States argues that the Japanese Commodity Tax would fall within (a), rendering (b) redundant if Congress intended remission of such a tax to constitute a bounty or grant. On the premise that the Japanese tax is “added to or included in the price of such or similar merchandise” when sold in Japan, see note 19, supra, the argument has merit. Whether Japanese manufacturers absorb or shift the Japanese Commodity Tax, however, is an economic issue not before us.

32 This court expressed the same view in United States v. Hammond Lead, 58 CCPA at 134-139, 440 F.2d at 1027-28, 1031. The prompt congressional provision of judicial review, supra note 13, while remaining silent with respect to this court’s description of the Secretarial function under the statute, further confirms Congress’ acquiescence, in the Treasury’s administrative practice.

We do not imply that the Secretary has carte blanche, or the right to be totally arbitrary or inconsistent in applying a long-standing practice, Whether the Secretary could, however, under appropriate conditions, change present practice and begin to deem excise tax remission alone a bounty or grant is not before us. The value and effect of administrative practice, and the Secretary’s authority to change it, have acquired statutory recognition in the field of customs. Under 19 USC 1315(d) (Supp. V 1975), a practice setting a particular duty, and found by the Secretary to have been uniform, can be changed to assess a higher duty, but only as to imports occurring at least 30 days after publication of the higher duty. In the Trade Act of 1974, Congress amended this section to exempt the assessment of countervailing duties from the 30 day delay provision and thus altered Treasury’s practice. §331(c), Tariff Act of 1974, 19 USC 1315(d) (Supp, V 1975). See [1974] U.S. Code Cong, ft Ad. News 7320.

33 Mr. Justice White’s dissent in Saxbe saw the statute there involved as leaving nothing open to construction, the administrative practice as in conflict with the statute, the Congress as not having been shown aware of the practice and its silence, which may have been due to unawareness, preoccupation or paralysis, as inadequate proof of acceptance. In the present case, “bounty” and “grant” have remained undefined by Congress ; the statute delegates to the Secretary the determination of what is a bounty or grant; the administrative practice is not in conflict with the statute, judicial decisions, or congressional expression; Congress has long and often been aware of the practice; and, concerning customs matters, Congress has in no manner been paralyzed.

1 The complaint alleged the following rates: Large television receivers (20%); Small television receivers (15%); Color television picture tubes - large (20%) and small (15%);Radio receivers - stereo (15%), other than stereo (and other than housed in metal cases of specified dimension) (10%), and other than stereo housed in metal cases of said specified dimension (5%); Radio-phonograph combinations (15%); Radio-television-phonograph combinations - if television qualifies for 20% rate (20%) and if television qualifies for 15% rate (15%,); Record players and phonographs (15%); Tape players, tape recorders, and radio/tape recorder combinations - stereo (15%) and other (10%).

2 The 5 to 40% range referred to by the Customs Court is shown in 1 W. Diamond, Foreign Tax and Trade Briefs 84.7 (1977), which notes that the commodity taxes “generally are paid by the manufacturer.”

3 This court noted in United States v. Hammond Lead Products, Inc., 58 CCPA 129, 136, C.A.D. 1017, 440 F.2d 1024, 1029 (1971), that “in the case of the countervailing duty assessment, no injury to a domestic industry need be shown.”

4 The Notice stated that “Information has been received . . . which raises a question as to whether certain payments, bestowals, rebates, or refunds granted by the Government of Japan upon the manufacture, production, or exportation of certain consumer electronic products constitute the payment or bestowal of a bounty or grant, directly or indirectly, within the meaning of section 303 of the Tariff Act of 1930 (19 U.S.C. 1303), upon the manufacture, production, or exportation of the merchandise to which the payments, bestowals, rebates, or refunds apply.”

5 The broad language could be construed to encompass the Japanese commodity tax.

6 If the majority remains convinced that the economic result of the remission of the Japanese commodity tax is decisive of the issue before us, it should at least remand the case to the Customs Court for development of a record on that point, a task that court is specially equipped to undertake. Failing that, I suggest that the rates of the Japanese commodity tax are such as to establish prima facie that the economic impact (e.g. competitiveness of Japanese exports vis-á-vis U. S. manufacturers) of remission of the tax would not be de minimis. Significantly, the United States Tariff Commission (now International Trade Commission) made the following statement in its report to the Senate Finance Committee, 5 Trade Barriers 39 (1974):

For all but a very few U.S. products, the differential between domestic and export prices which is attributable to the exemption of exports from internal consumption taxes is substantially lower than the price differential found in products of most other major trading nations resulting from the exemption of exports from their domestic consumption taxes. [Footnote omitted.

In its report, The Future Of U.S. Foreign Trade Policy, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. 5 (Comm. Print 1967), the Joint Economic Committee of the Congress stated:

The European Common Market practice of rebating their own indirect taxes on their exports and levying these same taxes on imports—a practice sanctioned, incidentally, by the rules of the GATT—constitutes a conspicuous form of discrimination against U.S. exports. Moreover, similar border adjustments by the United States would be an ineffective weapon, neither mitigating nor offsetting the discriminatory process, because the tax structure of the United States places relatively small emphasis on indirect taxes. This issue is one that the United States will have to resolve.

7 “That whenever any country . . . shall pay or bestow directly or indirectly, any bounty . . . upon the exportation of any article or merchandise from such country . . . .” There is no support for the statement in the majority opinion that there was “congressional refusal” to define the words “bounty” or “grant.” Customs Law dictates that the common meaning of such words is intended in the absence of evidence to the contrary. United States v. C.J. Tower & Sons, 48 CCPA 87, 89, C.A.D. 770 (1961) ; Meyer & Lange v. United States, 6 Ct. Cust. Appls. 181, T.D. 35436 (1915). Webster’s International Dictionary (1890) defines “bounty” as:

4. A premium offered or given . . . to encourage any branch of industry, as husbandry or manufactures.

It was merely customary legislative practice for Congress to leave it to the Treasury Department, subject to judicial review, to make individual determinations within such a broad definition.

8 Whether the “bounty or grant” in a particular case would be de minimis (not, therefore, warranting imposition of a countervailing duty) or what the net amount of the “bounty or grant” would be as a basis for imposition of a countervailing duty is, of course, another matter. Thus, as appellant has shown, the market value of the certificate in Downs was from 1.25 to 1.64 rubles per pood, and the excise tax remitted was 1.75 rubles per pood; whereas, the net bounty determined ranged from only .38 to .50 rubles per pood (T.D. 22814, 4 Treas. Dec. 184 (1901)). It is not disclosed what factors entered into the determination. See F.W. Woolworth Co. v. United States, 28 CCPA 239, CA. D. 151 (1940).

9 In Towne v. Eisner, the question was whether a stock dividend made in 1914, against surplus earned before the effective date of the Sixteenth Amendment, was taxable under the Income Tax Act of October 3, 1913. The lower court had decided for the taxpayer, treating the question as inseparable from interpretation of the Sixteenth Amendment. The Supreme Court disposed of the question upon consideration of the essential nature of a stock dividend, disregarding the fact that the dividend involved was based upon surplus earnings that accrued before the Sixteenth Amendment took effect, and quoting from its Opinion in Gibbons v. Mahon, 136 U.S. 549 (1890) as follows:

“A stock dividend really takes nothing from the property or the corporation, and adds nothing to the interests of the shareholders. Its property is not diminished, and their interests are not increased. . . . The proportional interest of each shareholder remains the same. The only change is in the evidence which represents that interest, the new shares and the original shares together representing the same proportional interest that the original shares represented before the issue of the new ones.” Gibbons v. Mahon, 136 U.S. 559, 560. In short, the corporation is no poorer and the stockholder is no richer than they were before. . . . What has happened is that the plaintiff’s older certificates have been split up in effect and have diminished in value to the extent of the value of the new. [Id. at 426-27.]

10 Paragraph E was substantially the same as section 303 of the Tariff Act of 1930 and as section 303(a)(1) under the 1970 amendment, the statute herein involved. Paragraph E was preceded by Paragraph E of section 4 Of the Tariff Act of 1913 (38 Stat. 114, 193); section 6 of the Tariff Act of 1909 (36 Stat. 11, 85); and section 5 of the Tariff Act of 1897 (30 Stat. 151, 205). Prior to the latter, paragraph 182 1/2 of the Tariff Act of 1894 (28 Stat. 509, 521) provided for payment of additional duty on sugar, syrups, and molasses where the exporting country paid a bounty on the export thereof; and paragraph 237 of the Tariff Act of 1890 (26 Stat. 567, 584) made similar provision in the case of sugar only. In its brief, the Government contends that the 1897 Act was intended to apply to the refund of taxes only to the extent that the “refund” exceeded the amount of tax actually paid (i.e. the “excessive remission”). This appears to have been so under the specific language of the 1890 and 1894 Acts. However, different language appeared in the subsequent acts, and the legislative history of the 1897 Act cited by the Government can hardly be used now to overturn the Supreme Court’s interpretation in Downs of “bounty” in the 1897 Act. The Government’s argument, of course, has no application to “grant” (added by the 1897 Act). If it did, it would imply that there was no Congressional purpose in adding “grant” to the language of the statute.

11 The law also provided for payment of an allowance of two pence per gallon “to any Distiller or Proprietor of . . . Spirits on the Exportation thereof from a Duty-free Warehouse, or in depositing the same in a Customs Warehouse.” However, this payment was not involved in the case.

12 Passavant held that in determining dutiable value or goods imported from Germany, there should be added to the net invoice price the amount of tax imposed upon the goods when sold by the manufacturer thereof for consumption or sale in Germany but remitted upon exportation of the goods.

13 As had the Government in its brief, saying of Downs:

The Russian bounty case was summed up in a single sentence in the opinion (187 U.S. 515): “When a tax is imposed on all sugar produced, but is remitted upon all sugar exported, then, by whatever process, or in whatever manner, or under whatever name it is disguised, it is a bounty upon exportation.”

14 Cf. E. Griswold, The Judicial Process 31 (1973): “In many areas precedents, especially ones of a few years’ standing, are not given very great weight. This in turn stimulates litigation on a great mass of questions . . . .”

15 This statement apparently dees not take account of the countervailing duties assessed by Treasury in Downs and the Government’s position in its brief before the Supreme Court in support thereof, wherein the Assistant Attorney General went so far as to say (R 236) :

For it seems that any special favor, benefit, advantage, or inducement conferred by the Government, even if it is given as a release from burden and is not a direct charge upon the Treasury, is fairly included in the idea and meaning of an indirect bounty.

16 If the Secretary concludes that a formal investigation is warranted, he is to initiate one, make a preliminary determination within six months, and make a final determination within twelve months.

17 Hearings on H.R. 1535 Before the House Committee on Ways and Means, 82d Cong., 1st Sess. 2, 16, 35, and 79 (1951). (H.R. 1535, which would have been entitled “Customs Simplification Act of 1951,” was introduced “by request” of the Secretary.) Hearings on H.R. 5505 Before the Senate Committee on Finance, S2d Cong. 2d Sess. 115, 124-25 (1952). (H.R. 5505 supplanted H.R. 1535 as a “clean bill.”)

* *[This refers to the concurring opinion to the U.S. Customs Court decision of April 12, 1977, available in the Library of the American Society of International Law. The decision is reproduced at 16 I.L.M. 520 (1977).]

18 The Department’s representative advised the Senate Finance Committee that an amendment to conform section 303 with administrative practice was needed to make the countervailing duty law fully consistent with Article VI of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. Hearings on H.R. 1612 (“Trade Agreements Extension Act of 1951”) Before the Senate Committee on Finance, 82d Cong., 1st Sess. 11 (1951).

19 The majority opinion notes an earlier unsuccessful attempt by Treasury in 1950, but says: “Congress’ failure to act or even speak against it [the Treasury proposal] reflected at least a then current willingness to allow that administrative practice to continue unabated and unchanged.” Such a comment ignores the principle stated in United States v. Douglas & Berry, supra. The correct conclusion to be drawn from failure of the Treasury proposal is that stated by Judge Newman. See United States v. Adolphe Schwob, Inc., 21 CCPA 116, 120, T.D. 46447 (1933).

20 Of particular significance, the report (Vol. VI at 30-31) states:

Several governments provide tax ? advantages to exporters. This is done usually by exempting or deferring taxes on income from export activities, or rebating other direct taxes associated with the production of exported products, or by accelerated amortization of assets used in production for export.

Under current GATT rules, indirect (consumption) taxes may be rebated (or not collected) on exported products, but rebates of direct taxes (income and certain other taxes) are not permitted. This rule is based on the premise that indirect taxes are fully shifted forward to the consumer, whereas direct taxes are not. To the extent, however, that the forward shifting of indirect taxes is incomplete, the full restitution of the domestic consumption tax at the border on exported products acts, in effect, as a subsidy of exports. [Footnote omitted.]

21 The court stated that litharge is a lead oxide, made from refined lead by a simple process and containing 937o primary lead metal. Its main use is in storage batteries and in the chemical and paint industries.

22 Following devaluation of the peso in 1954, Mexico increased export taxes on refined lead for the purpose of maintaining domestic supplies and keeping down domestic prices. Refined lead was made available to domestic users at a price approximating the world price minus what the export tax would have been. Exports of litharge were not subjected to the export tax, so that Mexican litharge producers could offer litharge in other countries at a price predicated on the domestic lead price unenhanced by the export tax.

23 The dissenting opinion concluded that the Customs Court had jurisdiction of the protest under section 516(b), citing Bradford Co. v. American Lithographic Co., 12 Ct. Cust. Appls. 318, T.D. 40318 (1924). Further, it stated that the Customs Court was correct in concluding that there was a bounty or grant, citing the definitions thereof in Nicholas and Downs, supra.

24 The statement that a countervailing duty is “penal” was repudiated in a 1972 Senate Finance Committee report. Infra, note 26.

25 Review can be sought in the Customs Court by “an American manufacturer, producer, or wholesaler of merchandise of the same class or kind as that described in such determination.”

26 In reporting out the amended bill, the Senate Finance Committee report (S. Rep. No. 92-1221, 92d Cong., 2d Sess. 8 (1972)) stated:

The Committee amendment providing judicial review to domestic producers in countervailing duty cases is necessitated because of a 1971 decision of the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals (United States v. Hammond Lead Products, Inc.) holding that judicial review was not available to American producers in countervailing duty cases. The Committee is concerned that the decision might adversely affect the ability of American producers to obtain meaningful relief against subsidized import competition under the Countervailing Duty Law (section 303 of the Tariff Act) because of administrative inaction or insufficient action, or because of excessive delay in the administrative process.

In addition, importers enjoy the right to judicial review in countervailing duty cases under existing law. The Committee believes that American producers as well as importers should be permitted to have the right to judicial review in countervailing duty cases as a matter of basic equity and fairness, and as a means to secure administration of the law in keeping with the intent of Congress reflected in the broad, explicit and mandatory terms used in section 303.

The Countervailing Duty Law requires the Secretary of the Treasury to assess an additional duty on imports of dutiable articles with respect to which a bounty or grant has been paid. The additional duty must be equal to the amount of the bounty or grant, thereby neutralizing the artificial advantage afforded the foreign product by virtue of the subsidy. Consequently, countervailing duties are not, nor were they ever intended to be, penal in nature: they are remedial in nature inasmuch as they operate to offset the effect of subsidies afforded foreign merchandise.