No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

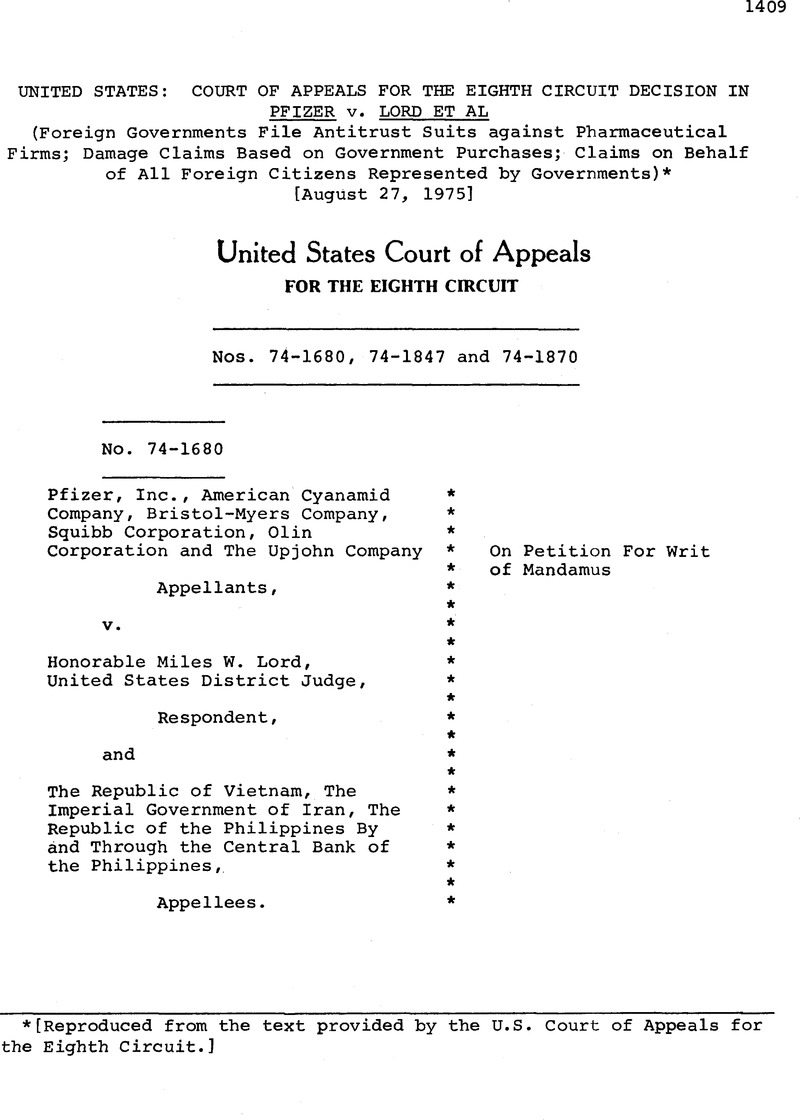

United States: Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit Decision in Pfizer v. Lord et al (Foreign Governments File Antitrust Suits against Pharmaceutical Firms; Damage Claims Based on Government Purchases; Claims on Behalf of All Foreign Citizens Represented by Governments)*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1975

Footnotes

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit.]

References

1 The governments involved in this appeal are the Government of India, the Imperial Government of Iran, the Republic of the Philippines, and the Republic of Vietnam. Several other governments filed similar suits after entry of the orders from which these appeals were taken.

2 The defendants are Pfizer, Incorporated, American Cyanamid Company, Bristol-Myers Company, Squibb Corporation, Olin Corporation and the Upjohn Company.

3 After a new government gained power m South Vietnam,we requested briefs of the parties and the United States as amicus curiae on the effect of those events on the right of the government known as The Republic of Vietnam (RVN, the former government) to prosecute this action.

The Justice Department contacted the State Department to ascertain whether the United States currently recognized any government for the territory of South Vietnam. The State Department replied in the negative, stating that the United States no longer recognized the RVN and that it had not yet recognized the new de facto government either. The State Department indicated that it did not contemplate any change in this posture in the near future, and it recommended that RVN's suit be dismissed rather than suspended.

The rule is that unrecognized governments may not maintain suits in state or federal courts. Guaranty Trust Co. v. United States, 304 U.S. 126, 136-41 (1938); Federal Republic of Germany v. Elicofon, 358 F.Supp. 747 (E.D.N.Y. 1972), aff'd. 478 F.2d 231 (2nd Cir. 1973), cert, denied .415 U.S. 931 (1974); accord, Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398, 408-12 (1964).

Dismissal without prejudice of Vietnam's claim would seem to extinguish any possibility for the nation of Vietnam to collect the damages it claims, since the statute of limitations apparently ran in 1974. Presumably, then, even if a new government were soon recognized, a new action could not be timely filed.

Another possibly proper course might be to suspend rather than dismiss the proceeding with regard to Vietnam for a reasonable time to see if a new government will be recognized, and if so, whether it would want to pursue this litigation. See, e.g. Bank of China v. Wells Fargo Bank & Union Trust Co., 190 F.2d 1010 (9th Cir. 1951); Republic of China v. Merchants Fire Assur. Corp., 30 F.2d 278 (9th Cir. 1929); Government of France v. Isbrandtsen-Moller Co., Inc. 4 8 F. Supp. 631 (S.D.N.Y.1943). Since we do not pass on the question of whether a foreign sovereign has standing as a “person” under § 4 of the Clayton Act, the district court will have to face the question of suspension or dismissal on remand. We need not decide whether Vietnam's parens patriae claim brought on behalf of its nationals should be dismissed or suspended since as we shall discuss the parens patriae claim fails to state grounds for relief.

4 The defendants also challenge the propriety of the district court's refusal to certify this question under § 1292(b). This court is without jurisdiction to review an exercise of the district court's discretion in refusing such certification. See United States v. 687.30 Acres of Land, 451 F.2d 667 (8th Cir. 1971), cert, denied sub nom.,Winnebago Tribe v. United States, 405 U.S. 1026 (1972); accord, Leasco Data Processing Equip. Corp. v. Maxwell, 468 F.2d 1326, 1344 (2nd Cir. 1972) (Friendly, J.); Note, Interlocutory Appeals in the Federal Courts Under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b), 88 Harv. L. Rev. 607, 616-617 (1975).

5 The use of parens patriae suits by the state on behalf of its citizens is ably discussed in Malina & Blechman, Parens Patriae Suits for Treble Damages Under the Antitrust Laws, 65 Nw. U. L. Rev. 193 (1970); Comment, Wrongs Without Remedy: The Concept of Parens Patriae Suits for Treble Damages Under the Antitrust Laws, 43 S.Cal. L. Rev. 570 (1970); Comment, State Protection of Its Economy and Environment; Parens Patriae Suits for Damages, 6 Colum. J. L. & Soc. Prob. 411 (1970).

6 Early cases which rejected a state's right to file a parens patriae claim were decided on the narrow ground that the Supreme Court lacked original jurisdiction under Article III, § 2 when the state was not asserting a separate interest from its citizens. Thus, in Oklahoma v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Ry. Co.,220 U.S. 277 (1911), Oklahoma sought to assert rights of shippers against a common carrier to restrain it from charging unreasonable rates within its jurisdiction. The Supreme Court denied the state the right to file an original suit in the Supreme Court since the suit did not involve any infringement of power of the State but rather special damage to its shippers. The Court observed:

We are of the opinion that the words, in the Constitution, conferring original jurisdiction on this court, in a suit “in which a State shall be a party,” are not to be interpreted as conferring such jurisdiction in every cause in which the State elects to make itself strictly a party plaintiff of record and seeks not to protect its own property, but only to vindicate the wrongs of some of its people or to enforce its own laws or public policy against wrongdoers, generally. Id. at 289.

See also Oklahoma v. Cook, 304 U.S. 387 (1938).

7 In 1969 the State of Hawaii sought to recover treble damages for overcharges for petroleum products sold to the State itself (the first or “proprietary” count), for damages to the general economy (the second or parens patriae count), and as the representative plaintiff for the class of all citizens with treble damage claims (the third or class action count). The district court dismissed the class action count and that was not appealed. The Supreme Court affirmed the Ninth Circuit's holding that the State could not recover for damages to the general economy under the parens patriae count. 405 U.S. 251 (1972) , aff'g. Hawaii v. Standard Oil Co., 431 F.2d 1282 (9th Cir. 1970). The Court held that the “business or property” limitation in the Clayton Act's treble damage provision meant that only damages to the State's commercial interests or enterprises were recoverable by the State; damage to the general economy was not compensable under the Act. 4 0.5 U.S. at 265. See also In re Multidistrict Vehicle Air Pollution, 481 F.2d 122, 126 (9th Cir. 1973).

8 For purposes of determining this question only, we will assume without deciding that the district court was correct in holding that foreign governments are “persons” entitled to bring treble damage actions under § 4 of the Clayton Act.

9 The Treaty of Amity & Economic Relations between the United States and Iran, August 15, 1955, [1957] 8 U.S.T. 899, T.I.A.S. No. 3853, is not to the contrary. Article 3, paragraph 2, reads as follows in relevant part:

Nationals and companies of either High Contracting Party shall have freedom of access to the courts of justice and administrative agencies within the territories of the other High Contracting Party, in all degrees of jurisdiction, both in defense and pursuit of their rights, to the end that prompt and impartial justice be done. Such access shall be allowed in any event, upon terms no less favorable than those applicable to nationals and companies of such other High Contracting Party or of any third country. . . .

This merely guarantees access to United States courts on the same terms available to United States nationals, not more favorable terms or additional remedies.

10 In Sardino v. Federal Reserve Bank, 361 F.2d 106, 111 (2nd Cir. 1966), Judge Friendly wrote:

The Government's second answer that “The Constitution of the United States confers no rights on non-resident aliens” is so patently erroneous in a case involving property in the United States that we are surprised it was made. Throughout our history the guarantees of the Constitution have been considered applicable to all actions of the Government within our borders––and even to some without. Cf. Reid v. Covert, 354 U.S. 1, 5, 8, 77 S.Ct. 1222, 1 L.Ed.2d 1148 (1957). This country's present economic position is due in no small part to European investors who placed their funds at risk in its development, rightly believing they were protected by constitutional guarantees; today,for other reasons, we are still eager to attract foreign funds. In Russian Volunteer Fleet v. United States, 282 U.S. 481, 489, 491-492, 51 S.Ct. 229, 75 L.Ed..473 (1931), the Court squarely held that an alien friend is entitled to the protection of the Fifth Amendment's prohibition of taking without just compensation––even when his government was no longer recognized by this country. And the Court has declared unequivocally, with respect to non-resident aliens owning property within the United States, that they “as well as citizens are entitled to the protection of the Fifth Amendment.”