No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 May 2017

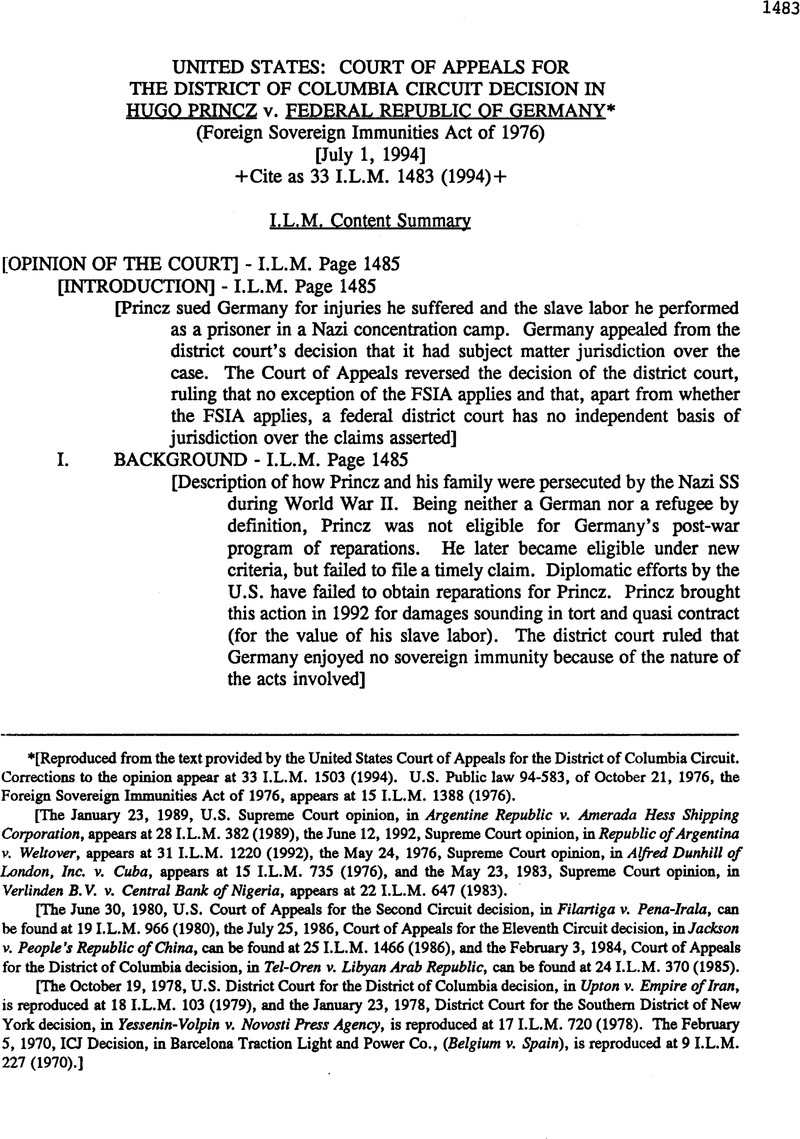

[Reproduced from the text provided by the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Corrections to the opinion appear at 33 I.L.M. 1503 (1994). U.S. Public law 94-583, of October 21, 1976, the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976, appears at 15 I.L.M. 1388 (1976).

[The January 23, 1989, U.S. Supreme Court opinion, in Argentine Republic v. Amerada Hess Shipping Corporation, appears at 281.L.M. 382 (1989), the June 12, 1992, Supreme Court opinion, in Republic of Argentina v. Weltover, appears at 31 I.L.M. 1220 (1992), the May 24, 1976, Supreme Court opinion, in Alfred Dunhill of London, Inc. v. Cuba, appears at 15 I.L.M. 735 (1976), and the May 23, 1983, Supreme Court opinion, in Verlinden B.V. v. Central Bank of Nigeria, appears at 22 I.L.M. 647 (1983).

[The June 30, 1980, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit decision, in Filartiga v. Pena-Irala, can be found at 191.L.M. 966 (1980), the July 25, 1986, Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit decision, in Jackson v. People's Republic of China, can be found at 251.L.M. 1466 (1986), and the February 3, 1984, Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia decision, in Tel-Oren v. Libyan Arab Republic, can be found at 24 I.L.M. 370 (1985).

[The October 19, 1978, U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia decision, in Upton v. Empire of Iran, is reproduced at 18 I.L.M. 103 (1979), and the January 23, 1978, District Court for the Southern District of New York decision, in Yessenin-Volpin v. Novosti Press Agency, is reproduced at 171.L.M. 720 (1978). The February 5, 1970, Id Decision, in Barcelona Traction Light and Power Co., (Belgium v. Spain), is reproduced at 9 I.L.M. 227 (1970).]

1 Our dissenting colleague Judge Wald suggests, in effect, that because the Congress has not expressly excluded suits for the violation of jus cogens norms from the scope of § 1605(a)(1), international law requires that we “construe the [FSIA] to encompass an implied waiver exception” for such suits, thus providing jurisdiction over Mr. Princz’s claims. Dis. Op. at 17. While it is true that “international law is a part of our law,” Paquete Habana, 175 U.S; at 700, it is also our law that a federal court is not competent to hear a claim arising under international law absent a statute granting such jurisdiction. Judge Wald finds that grant through a creative, not to say strained, reading of the FSIA against the background of international law itself. We think that something more nearly express is wanted before we impute to the Congress an intention that the federal courts assume jurisdiction over the countless human rights cases that might well be brought by the victims of all the ruthless military juntas, presidents-for-life, and murderous dictators of the world, from Idi Amin to Mao Zedong. Such an expansive reading of § 1605(a)(1) would likely place an enormous strain not only upon our courts but, more to the immediate point, upon our country’s diplomatic relations with any number of foreign nations. In many if not most cases the outlaw regime would no longer even be in power and our Government could have normal relations with the government of the day—unless disrupted by our courts, that is. Like Judge Wald, we recognize that this suit may represent Mr. Princz's last hope of reparation. Still, we cannot responsibly make the inferential leap that would be required in order to provide him with the federal forum be look.

1 At this stage, we may not question Princz's rendition of the horrors he suffered. In reviewing a motion to dismiss based in part on Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6), we must accept all of the plaintiffs allegations in the complaint as true.See Moore v. Agency for Intl Dev% 994 F.2d 874, 875 (D.C. Cir. 1993).

2 Section 1602 provides that “[c]laims of foreign states to immunity should henceforth be decided by courts of the United States and the States in conformity with the principles set forth in this chapter.“ 28 U.S.C. 16O2 (1988) (emphaais added).

3 I disagree, however, with the Siderman court's finding that the Supreme Court's approach in Amerada Hess, 488 U.S. at 436, constrained it to hold that because the FSIA does not specifically provide for an exception to immunity when a state violates a jus cogens norm, such a violation cannot confer jurisdiction under the FSIA. Siderman, 965 F.2d at 718-19. The Ninth Circuit failed to recognize that when a state transgresses a jus cogens norm, it does bring itself within the confines of an exception to the FSIA—the implied waiver exception.

4 Although the jus cogens terminology gained new coinage after World War II and the Nuremberg trials, at the time of the war the norms prohibiting genocide and enslavement were already universally accepted as nonderogable. See Klein, Customary International Law, 13 YALE J.INT'LL. at 340 (“Long before Hitler came to power, the international community had been unanimous in considering acts such as those perpetrated by the Nazis to be criminal.“).

5 I of course hazard no opinion on the substantive validity of Germany's nonjurisdictional defenses and the ultimate availability of monetary relief for Princz. Because we found that the district court's finding of subject-matter jurisdiction was immediately appealable, the merits of this case are not before us