No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

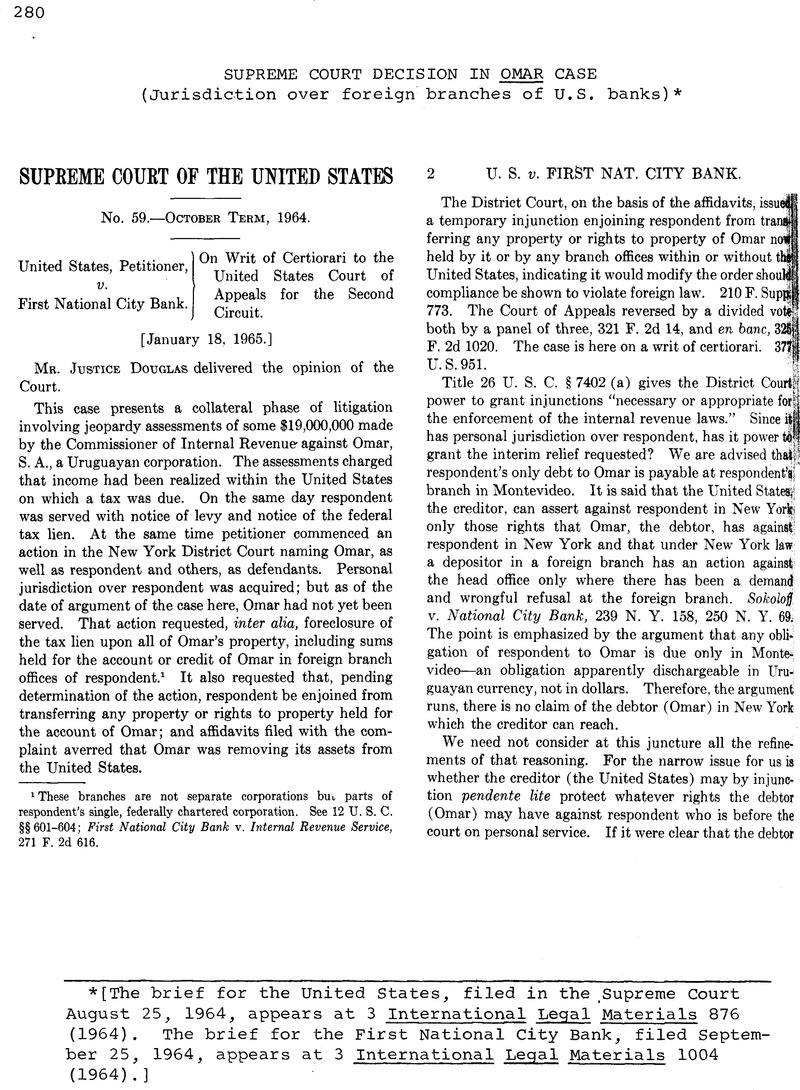

[The brief for the United States, filed in the Supreme Court August 25, 1964, appears at 3 International Legal Materials 876 (1964). The brief for the First National City Bank, filed September 25, 1964, appears at 3 International Legal Materials 1004 (1964).]

1 These branches are not separate corporations but parts of respondent’s single, federally chartered corporation. See 12 U. S. C. §§601-604; First National City Bank v. Internal Revenue Service, 271 F. 2d 616.

1 There is also of course the possibility that Omar might enter a eral appearance as it apparently did in the Tax Court when it lits petition of May 20, 1963, for a redetermination of the defileies on the basis of which the present jeopardy assessments were de.

2 Rule 4 (e) effective July 1, 1963, reads in relevant part:

Whenever a statute or rule of court of the state in which the net court is held provides (1) for service of a summons, or of a ice, or of an order in lieu of summons upon a party not an inhabit of or found within the state, or (2) for service upon or notice him to appear and respond or defend in an action by reason of attachment or garnishment or similar seizure of his property ited within the state, service may in either case be made under circumstances and in the manner prescribed in the statute or %9

3 Rule (f), also effective July 1, 1963, reads in relevant part:

All process other than a subpoena may be served anywhere within territorial limits of the state in which the district court is held, l, when authorized by a statute of the United States or by these as, beyond the territorial limits of that state.”

4 The Court of Appeals reached these conclusions on the basis of CPLR §10003, 7B McKinney’s Consol. Laws Ann. 10003: “This act shall apply to all actions hereafter commenced. This act shall also apply to all further proceedings in pending actions, except to the extent that the court determines that application in a particular pending action would not be feasible or would work injustice, in which event the former procedure applies. Proceedings pursuant to law in an action taken prior to the time this act takes effect shall not be rendered ineffectual or impaired by this act.”

5 That the Government has not yet attempted to obtain personal jurisdiction over Omar is not significant in light of the fact that until now the Government’s primary contention has been that the District Court’s personal jurisdiction over the respondent bank was by itself an adequate basis for the issuance of the temporary injunction. As the Government said in its petition for rehearing before the Court of Appeals: “The jurisdictional basis, then, for the injunction issued by the District Court was personal jurisdiction over the Bank. Certainly, at this stage of the proceeding, it is inconsequential whether the District Court has jurisdiction over a res or over the taxpayer.” The Government went on to say that if this contention was rejected, then it wished to argue that the tax lien had attached to Omar’s deposits and that these deposits “constitute rights to property which were within the jurisdiction of the District Court.” Finally the Government stated: “It is only in the event that the Court concludes the lien does not attach to such deposits that personal jurisdiction over Omar becomes relevant. In such event the Government should be afforded an opportunity to obtain personal jurisdiction over Omar and the injunction should stand pending such efforts.” Even before this Court the Government argues alternatively that “the District Court had authority to enter the temporary injunction to preserve funds over which it had jurisdiction quasi in rem,” a contention upon which, as noted previously, we do not pass.

1 Affidavit of William R. T. Gottlieb, one of the investigating agents.

2 Cf. Penn v. Lord Baltimore, 1 Vesey, Sr. 444, 454 (ch. 1750) (1st Am. ed. 1831); Deschenes v. Tollman, 248 N. Y. 33, 161 N. E. 321.

3 Internal Revenue Code of 1954, § 7402 (a), provides:

“To Issue Orders, Processes, and Judgments.—The district courts of the United States at the instance of the United States shall have such jurisdiction to make and issue in civil actions, writs and orders of injunction, and of ne exeat republica, orders appointing receivers, and such other orders and processes, and to render such judgments and decrees as may be necessary or appropriate for the enforcement of the internal revenue laws. The remedies hereby provided are in addition to and not exclusive of any and all other remedies of the United States in such courts or otherwise to enforce such laws.”

4 Compare De Beers Consol. Mines, Ltd. v. United States, 325 U. S. 212; Appalachian Coals, Inc. v. United States, 288 U. S. 344, 377.

5 Compare Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U. S. 398.

6 Hall Signal Co. v. General R. Signal Co., 153 F. 907; A. H. Bull Steamship Co. v. National Marine Engineers’ Beneficial Assn., 250 F. 2d 332, 337.

7 It became effective on September 1, 1963. The freeze order was issued on October 31, 1962. Section 302 provides:

“(a) Acts which are the basis of jurisdiction. A court may exercise personal jurisdiction over any non-domiciliary, or his executor or administrator, as to a cause of action arising from any of the acts enumerated in this section, in the same manner as if he were a domiciliary of the state, if, in person or through an agent, he:

“1. transacts any business within the state; or

“2. commits a tortious act within the state, except as to a cause of action for defamation of character arising from the act; or

“3. owns, uses or possesses any real property situated within the state.

“(b) Effect of appearance. Where personal jurisdiction is based solely upon this section, an appearance does not confer such jurisdiction with respect to causes of action not arising from an act enumerated in this section.”

8 The lame suggestion is made by the Government that Omar would voluntarily make a general appearance to defend the suit. In light of the fact that Omar had quite evidently purposefully withdrawn most of its property from the jurisdiction, including the property here in question, an appearance voluntarily putting this very property in jeopardy would have been most surprising. The Government makes the further argument that Omar might have attempted to make a limited appearance to contest the title to some other property over which the District Court had clear quasi in rem jurisdiction (an account with Lehman Bros, in New York has been attached); and since the limited appearance might not be recognized, but instead treated as a general appearance, personal jurisdiction would be obtained. (There is a split of authority as to whether limited appearances are permitted. See United States v. Balanovski, 236 F. 2d 298 (C. A. 2d Cir.), cert, denied, 352 U. S. 968, and cases cited therein. See also Developments in the Law: State-Court Jurisdiction, 73 Harv. L. Rev. 909, 953 (1960). Whether or not a rule against limited appearances should prevail in our federal courts, it is clear that no argument for having such a rule could extend so far as to authorize a court, by reason of its having quasi in rem jurisdiction over one piece of property, to use whatever naked power is at its command to freeze all property wherever located, which could ’ conceivably be affected by a personal judgment.

9 Simonson involved a suit brought in 1960 in New York against ’ an Arizona bank. The trial court held that there was no personal jurisdiction over the defendant under existing statutes. By the time the plaintiff’s appeal on this issue reached the Court of Appeals, § 302 had become effective and appellant tried to rely on it. The court held that § 302 did not retroactively apply to validate the service that had been made upon the Arizona bank, and affirmed the dismissal of the complaint.

10 See Simonson v. International Bank, 14 N. Y. 2d 281, 288, 251 N. Y. S. 2d 433, 439; Purdy Co. v. Argentina, 333 F. 2d 95, cert, denied, — U. S. — (decided under the Illinois statute on which § 302 was patterned). Compare Grobark v. Addo Machine Co., 16 Ill. 2d 426; Insull v. New York World-Telegram Corp., 273 F. 2d 166; National Gas Appliance Corp. v. AB Electrolux, 270 F. 2d 472.

11 Foreign Exchange Rates, N. Y. Times, Oct. 31, 1962, p. 47, col. 5; N. Y. Times, Jan. 11, 1965, p. 37, col. 4.

12 The Court’s very assertion that the Government changed its theory is belied by the statement, prominently featured in the petition for rehearing, that “The Government contended in the brief heretofore filed in this Court that there is every likelihood that personal jurisdiction over Omar can be effectuated . . . .” Of course, the Government argued alternative theories below just as it has done here. The statements quoted by the Court (gleaned from a footnote) indicate only that the Government (rightly, I think) regarded the personal jurisdiction argument as its weaker point.

13 The Government’s delay in obtaining personal jurisdiction is particularly significant because of the unknowns and imponderables with which the case in its present posture is saturated. Thus, we have no firm indication of what Uruguayan law is with respect to any aspect of this action, no indication of the effect freeze orders would have on this country’s banking interests, and Omar, the foreign taxpayer whose interests are most at stake, is not before the Court. Can it be doubted that a decision upon the propriety of the novel use of judicial power here involved could be much better made if the issue were presented in a context with some of the unknowns removed? Had the Government not delayed but, instead, proceeded (if possible) to acquire personal jurisdiction over Omar, and then judgment and execution (if possible) against the Montevideo account, the case could come before us with most of this opaqueness removed. Omar could have presented the issue of the validity of the freeze order as a defense to an ultimate levy upon the account; the issue would not be moot at that stage because there would have been no earlier time at which Omar could have attacked the order without running the risk of being subjected to the personal jurisdiction of the court, and, as a matter of sound judicial principle, the Government should not be permitted to levy successfully upon the account when its ability to do so stems from an improper freeze order.

14 Section 313 of New York Civil Practice Law and Rules provides:

“A person domiciled in the state or subject to the jurisdiction of the courts of the state under section 301 or 302, or his executor or administrator, may be served with the summons without the state, in the same manner as service is made within the state, by any person authorized to make service within the state who is a resident of the state or by any person authorized to make service by the laws of the state, territory, possession or country in which service is made or by any duly qualified attorney, solicitor, barrister, or equivalent in such jurisdiction.”

15 Rule 70 provides in relevant part:

“If a judgment directs a party to execute a conveyance of land or to deliver deeds or other documents or to perform any other specific act and the party fails to comply within the time specified, the court may direct the act to be done at the cost of the disobedient party by some other person appointed by the court and the act when so done has like effect as if done by the party.”

16 United States v. Harden, 41 D. L. R. 2d 721; Government oj India v. Taylor, [1955] A. C. 491 (H. L.); Peter Buchanan Ld. & Macharg v. McVey, [1955] A. C. 516 (Eire Sup. Ct.). For enforcement of tax claims between States see Moore v. Mitchell, 30 F. 2d 600, aff’d on other grounds, 281 U. S. 18; Colorado v. Harbeck, 232 N. Y. 71, 133, N. E. 357; but see contra, Oklahoma v. Rodgers, 238 Mo. App. 1115, 193 S. W. 2d 919. Tax treaties may be used to change the general international understanding. See Owens, United States Income Tax Treaties, 17 Rutgers L. Rev. 428, 449-451 (1963). We have no tax treaty with Uruguay; Treaties in Force, 205 (1964).

17 Nations, generally chary of having foreign officials enter their borders even for purposes of serving process, are even more unlikely to look with favor upon a foreign official entering in an attempt to enforce a tax judgment. See Smit, International Aspects of Federal Civil Procedure, 61 Col. L. Rev. 1031, 1040 (1961); Harvard Research in International Law, Draft Convention on Judicial Assistance, 33 Am. J. Int’l L. Spec. Supp. II, 43-65 (1939); Jones, International Judicial Assistance: Procedural Chaos and a Program for Reform, 62 Yale L. J. 515, 534-537 (1953); Longley, Serving Process, Subpoenas and Other Documents in Foreign Territory, A. B. A. Section of Int’l and Comp. Law 34 (1959).

The Court derives support for such a bizarre procedure from the fact that “the District Court remains open to the Executive Branch,” (ante, p. 6). But certainly the Court cannot justify a procedure at odds with proper international practice simply because the Executive has not expressed a contrary wish.

I doubt very much whether before today’s decision even our own State Department would have found it easy to lend its aid, by way of issuing a passport or otherwise, to such a novel international adventure.

18 The Court places reliance on New Jersey v. New York City, 283 U. S. 473, an inapposite case in which the Court enjoined New York City from taking its garbage out to sea and dumping it off the New Jersey coast. No international problem was involved, nor any question of personal jurisdiction, enforcement, or rights of third parties. The garbage left our territorial jurisdiction on a circular route calculated to return it in an offensive manner. The Court had clear jurisdiction to prevent it from beginning that journey.

19 This last feature was heavily relied upon in United States v. Morris & Essex R. Co., 135 F. 2d 711, a tax case in which the taxlien statute could have been used directly.

Prior to the recent amendments of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 4 (e), a federal district court could not obtain quasi in rem jurisdiction over a debt owed to an absent defendant. Big Vein Coal Co. v. Read, 229 U. S. 31.

20 Those policy considerations which enter into a jurisdictional determination once it is decided that naked power exists are those which would apply in the generality of cases raising the jurisdictional question. Those considerations which are peculiar to this case relate to the question whether, in this instance, jurisdiction, once established, should be exercised.

21 The regulation provides:

“Sec. 301.6332-1 [as amended by T. D. 6746] Surrender of property to levy.

“(a) Requirement—(1) In general. Any person in possession of (or obligated with respect to) property or rights to property subject to levy upon which a levy has been made shall, upon demand of the district director, surrender such property or rights (or discharge such obligation) to the district director, except such part of the property or right as is, at the time of such demand, subject to an attachment or execution under any judicial process.

“(2) Property held by banks. Notwithstanding subparagraph (1) of this paragraph, if a levy has been made upon property or rights to property subject to levy which a bank engaged in the banking business in the United States or a possession of the United States is in possession of (or obligated with respect to), the Commissioner shall not enforce the levy with respect to any deposits held in an office of the bank outside the United States or a possession of the United States, unless the notice of levy specifies that the district director intends to reach such deposits. The notice of levy shall not specify that the district director intends to reach such deposits unless the district director believes—

“(i) That the taxpayer is within the jurisdiction of a United States court at the time the levy is made and that the bank is in possession of (or obligated with respect to) deposits of the taxpayer in an office of the bank outside the United States or a possession of the United States; or

“(ii) That the taxpayer is not within the jurisdiction of a United States court at the time the levy is made, that the bank is in possession of (or obligated with respect to) deposits of the taxpayer in an office outside the United States, or a possession of the United States, and that such deposits consist, in whole or in part, of funds transferred from the United States or a possession of the United States in order to hinder or delay the collection of a tax imposed by the Code. For purposes of this subparagraph the term “possession of the United States” includes Guam, the Midway Islands, the Panama Canal Zone, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, American Samoa, the Virgin Islands, and Wake Island.”

22 Código de Procedimiento Civil (Couture, 1952). There have been no amendments, Index to Latin American Legislation, Library of Congress.

23 See Ehrenzweig, Conflict of Laws, §§45, 46; Hilton v. Guyot, 159 U. S. 113 (1962).

24 The regulation makes no distinction between parent and branch offices.

25 Reese, The Status in This Country of Judgments Rendered Abroad, 50 Col. L. Rev. 783 (1950).

26 28 U. S. C. § 1655 governing lien enforcement against absent defendants provides:

“Lien Enforcement; Absent Dependants.

“In an action in a district court to enforce any lien upon or claiip to, or to remove any incumbrance or lien or cloud upon the title to, real or personal property within the district, where any defendant cannot be served within the State, or does not voluntarily appear, the court may order the absent defendant to appear or plead by a day certain.

“Such order shall be served on the absent defendant personally if practicable, wherever found, and also upon the person or persons in possession or charge of such property, if any. Where personal service is not practicable, the order shall be published as the court may direct, not less than once a week for six consecutive weeks.

“If an absent defendant does not appear or plead within the time allowed, the court may proceed as if the absent defendant had been served with process within the State, but any adjudication shall, as regards the absent defendant without appearance, affect only the property which is the subject of the action. When a part of the property is within another district, but within the same state, such action may be brought in either district.

“Any defendant not so personally notified may, at any time within one year after final judgment, enter his appearance, and thereupon the court shall set aside the judgment and permit such defendant to plead on payment of such costs as the court deems just.”

27 See Bluebird Undergarment Corp. v. Gomey, 139 Misc. 742, 249 N. Y. S. 319; Cronan v. Schilling, 100 N. Y. S. 2d. 474, aff’d 282 App. Div. 940, 126 N. Y. S. 2d 192; Newton Jackson, Inc. v. Animashun, 148 N. Y. S. 2d 66; McCloskey v. Chase Manhattan Bank, 11 N. Y. 2d 936; Zimmerman v. Hicks, 7 F. 2d 443, aff’d sub. nom., Zimmermann v. Sutherland, 274 U. S. 253. And see Richardson v. Richardson [1927] 137 L. T. R. (n. s.) 492; Comment, 56 Mich. L. Rev. 90 (1957); Note, 48 Cornell L. Q. 333 (1963).

The bank account is a contract for payment on demand at the Montevideo branch. If demand were wrongfully refused, a cause of action for breach of contract would be created on which Omar could sue in New York. Thus, analytically, it is not the account itself which would become payable in New York, but damages for breach of the contract to pay on demand in Montevideo.

28 Section 3670 is now Internal Revenue Code of 1954, § 6321. It provides:

“If any person liable to pay any tax neglects or refuses to pay the same after demand, the amount (including any interest, additional amount, addition to tax, or assessable penalty, together with any costs that may accrue in addition thereto) shall be a lien in favor of the United States upon all property and rights to property, whether real or personal, belonging to such person.”

29 See Comment, 56 Mich. L. Rev. 90 (1957).

30 E. g., Equitable Life Assurance Society of the United States v. United States, 331 F. 2d 29; United States v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 256 F. 2d 17; but see United States v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 130 F. 2d 149.

31 Equitable Life Assurance Society of the United States v. United States, 331 F. 2d 29, 33.

32 Crane v. Commissioner, 331 U. S. 1. See also American Banana Co. v. United Fruit Co., 213 U. S. 347, at 356-357.

33 Richardson v. Richardson, [1927] 137 L. T. R. (n. s.) 492.

34 If the law of Uruguay were known, New York might look to it as a matter of conflicts law.

I would not decide at this juncture whether federal courts in all situations would be required to enforce liens against property which the State would hold to be within its jurisdiction.

35 See n. 18, supra.

36 Under the Court’s opinion there appears, even now, to be no limit on the further length of time in which the Government can delay before acquiring personal jurisdiction over Omar.