No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

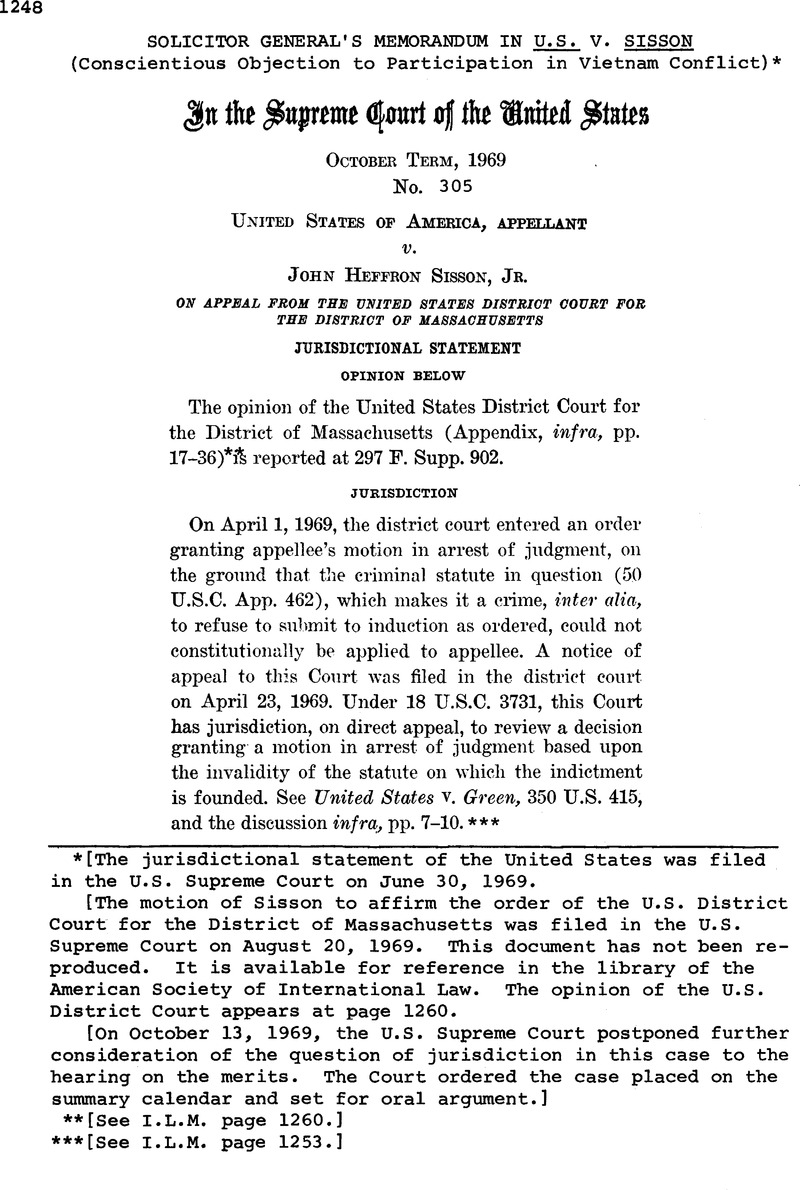

[The jurisdictional statement of the United States was filed in the U.S. Supreme Court on June 30, 1969.

[The motion of Sisson to affirm the order of the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts was filed in the U.S. Supreme Court on August 20, 1969. This document has not been reproduced. It is available for reference in the library of the American Society of International Law. The opinion of the U.S. District Court appears at page 1260.

[On October 13, 1969, the U.S. Supreme Court postponed further consideration of the question of jurisdiction in this case to the hearing on the merits. The Court ordered the case placed on the summary calendar and set for oral argument.]

** [See I.L.M. page 1260.]

*** [See I.L.M. page 1253.]

1 “Tr.” refers to the transcript of proceedings at trial.

2 He also claimed, but the court did not decide the question (see App. 17–18, 23–24), that, ii the court could not adjudge the relevant issue of the legality of the war in Vietnam, the trial violated due process.

* [See I.L.M. page 1250.]

3 The court stated, however, that it did not follow from this holding that appellee could not constitutionally be conscripted “for non-combat service there or elsewhere” (App. 32).

4 The court, in characterizing this claim as merely a reiteration of appellee’s “older contention” (App. 18), apparently accepted his position that the “establishment” clause argument was implicit in the original motion to dismiss the indictment, in view of his assertion in connection therewith of a “right of conscience.”

5 “The indictment, which was in the standard form, merely charged that appellee, on or about April 17, 1968, knowingly refused to obey the order of his local Selective Service board to submit to induction; That appellee claimed to be a conscientious objector was made clear in his memorandum in support of his pre-trial motion to dismiss the indictment; the memorandum, however, did not explain the non-religious or other specific nature of his conscientious objector beliefs. See United States v. Sisson, supra, 294 F. Supp at 519.

6 Although some language in United States v. Zisblatt, 172 F.2d 740, 741-742 (C.A. 2), would seem to support the notion that any recourse to facts outside the indictment, even for such a limited purpose, renders unappealable the district judge’s decision, the court of appeals there was not dealing with the situation like that presented here, where the fact which is noticed appears without dispute from the record.

7 Here the indictment was based on 50 U.S.C. App. 462, as applied to appellee. But the lower court’s puling not only held that statute invalid in the instant circumstances, it also held unconstitutional the substantive provision relative to the exemption of constitutional objectors—50 U.S.C. App. 456 (j) (see App. 34–36).

8 A threshold issue involves the district court’s ruling that appellee possessed the requisite standing to raise the claim of unconstitutional application of the Selective Service Act, a holding in conflict with decisions of the Second and Ninth Circuits. United States v. Bolton, 192 F. 2d 805 (C.A. 2); United States v. Mitchell 369 F. 2d 323 (C.A. 2), certiorari denied, 386 U.S. 972; Richter v. United States, 181 F. 2d 591, 594 (C.A. 9), certiorari denied, 340 U.S. 892. Appellee’s induction into the Armed Forces would not necessarily have resulted in his being sent to Vietnam. Here the court relied in part (294 F. Supp. at 512–513) on the fact that, at the time a serviceman is ordered to go to Vietnam, other considerations bearing on justiciability may prevent a court from adjudicating his claims that the conflict there is illegal or immoral (see, e.g., Luftig v. McNamara, 373 F. 2d 664 (C.A.D.C.), certiorari denied, 387 U.S. 945; Mora v. McNamara, 387 F. 2d 862 (C.A.D.C), certiorari denied, 389 U.S. 934). But that has little bearing on the crucial issue here whether, prior to such time as he is confronted by an order sending him to Vietnam, appellee can be said to have a sufficiently direct interest in the questions he raises concerning the Vietnam situation to accord him legal standing to litigate them. See generally Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83. We preserve that issue for further elaboration if the Court gives plenary consideration to the instant case.

9 The issue is raised in two presently pending petitions for writs of certiorari: Vaughn v. United States, No. 35 Misc., 1969 Term, and McQueary v. United States, No. 88 Misc., 1969 Term. See also Welsh v. United States, No. 76, 1969 Term. In opposing certiorari in those cases we have taken the position that Congress, consistent with the First Amendment, may exclude from conscientious objector status those whose opposition to war stems, in the words of amended Section 6 (j), from “essential political, sociological, or philosophical views or a merely personal moral code” (see note 10, infra). We recognize that, in view of the filing of this jurisdictional statement, the Court may wish to act on all of these cases simultaneously, and may thus desire to defer action on these petitions should plenary consideration be given to the instant case.

10 At the time Seeger was decided, Section 6(j) read: Nothing contained in this title shall be construed to require any person to be subject to combatant training and service in the armed forces of the United States who, by reason of religious training and belief, is conscientiously opposed to participation in war in any form. Religious training and belief in this connection means an individual’s belief in a relation to a Supreme Being involving duties superior to those arising from any human relation, but does not include essentially political, sociological, or philosophical views or a merely personal moral code.

In 1967 the statute was amended to its present form to comply with the effect of the Seeger holding

Nothing contained in this title shall be construed to require any person to be subject to combatant training and service in the armed forces of the United States who, by reason of religious training and belief, is conscientiously opposed to participation in war in any form. As used in this subsection, the term “religious training and belief” does not include essentially political, sociological, or philosophical views, or a merely personal moral code.