No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

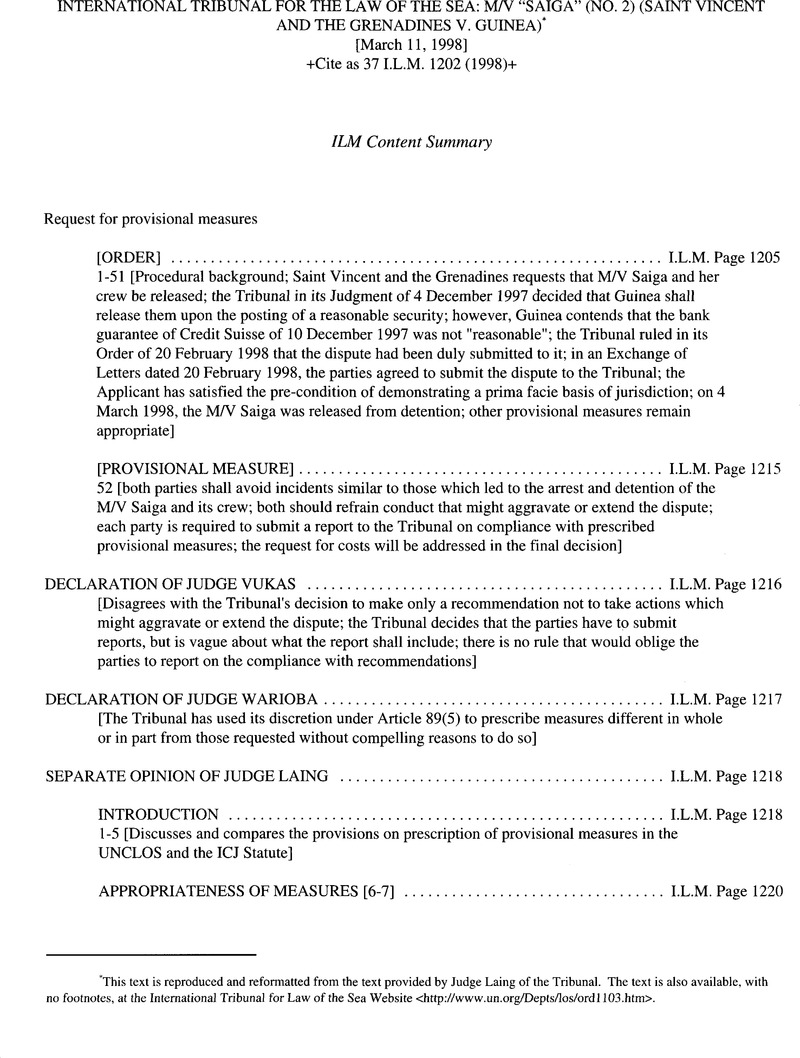

This text is reproduced and reformatted from the text provided by Judge Laing of the Tribunal. The text is also available, with no footnotes, at the International Tribunal for Law of the Sea Website <http://www.un.org/Depts/los/ordll03.htm>

1 See generally, Lawrence Collins, Essays in International Litigation and the Conflict of Laws (1994), pp. 169-71. This rationale for provisional measures is readily evident in a significant majority of the cases mentioned in notes 10, 19, and 24 where the ICJ ordered measures.

2 See Jerzey Sztucki, Interim Measures of Protection in the Hague Court — An Attempt at a Scrutiny (1983), pp. 1-15-

3 Merrills, J.G., “Interim Measures of Protection and the Substantive Jurisdiction of the International Court,” 36 Camb. L.J. (1977), pp. 86– 109 CrossRefGoogle Scholar, at p. 108; Collins pp. 169-70.

4 Art. 290:1 provides for the prescription, not indication, of provisional measures. To some, it may be encouraging to perceive that sovereigns would so agree that they could be bound by a judicial order. Nevertheless, the potential addressees of this provision and of provisional measures also include non-State parties to disputes (commercial entities and certain intergovernmental agencies). The addition of this range of addressees underscores the point in the text.

5 It is useful to recall that two of the leading works on provisional measures are squarely based on comparative law precedents and analogies and propose that a general principle of law governs the topic. See the books by Elkin and Dumwald referred to at notes 9 and 14. In his recent work, Collins firmly states his support of the notion that the principle underlying provisional measures is a general principle of law. Collins, pp. 169-71.

6 The same can be said in relation to the novel and unprecedented institution of prompt release of ships and crew in Art. 292.

7 Sztucki, p. 15.

8 Emphasis added.

9 Matters respectively covered by UNCLOS art. 288 and UNCLOS, Annex VI, art. 21, on the one hand, and UNCLOS, Annex VI, art. 20, on the other. See Elkind, Jerome B., Interim Protection — A Functional Approach (1981), pp. 170–77Google Scholar, 192. Note Merrills 1997, pp. 97-104, esp. p. 101.

10 See, e.g., Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. Case (United Kingdom v. Iran) (Interim Protection), Order of 6 July 1951, ICJ Reports 1951 (hereafter Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. Case), p. 93.

11 See Case Concerning the Land and Maritime Boundary between Cameroon and Nigeria (Cameroon v. Nigeria) (Provisional Measures), Order of 15 March 1996, ICJ Reports 1996 (hereafter Land & Maritime Boundary), p. 21 ¶ 30; Case Concerning Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Yugoslavia, Serbia and Montenegro) (Provisional Measures), Order of 13 September 1993, ICJ Reports 1993 (hereafter Genocide Convention #2), pp. 337-38, ¶ 24; Case Concerning Passage through the Great Belt (Finland v. Denmark) (Provisional Measures), Order of 29 July 1991, ICJ Reports 1991 (hereafter Great Belt), p. 15, ¶ 14; Case Concerning United States Diplomatic and Consular Staff in Tehran (Provisional Measures), Order of 15 December 1979, ICJ Reports 1979 (hereafter U.S. Staff Case), p. 13, ¶ 15; Nuclear Test Case (New Zealand v. France) (Interim Protection), Order of 22 June 1972, ICJ Reports 1972 (hereafter Nuclear Test - New Zealand), p. 137, ¶ 14; Nuclear Test Case (Australia v. France) (Interim Protection), Order of 22 June 1972, ICJ Reports 1972 (hereafter Nuclear Test Case - Australia), p. 101, ¶ 13.

12 Generally, the citation of jurisdictional provisions in the Convention or other source and a basic factual background.

13 It will be noted that this formulation does not address the adequacy or otherwise of rebuttal evidence by the Respondent. Black's Law Dictionary (6th ed. 1990), pp. 1189-90. Presumably the Respondent has the liberty of coming forward and developing a case based on such contradictory evidence and the decision-maker will take this into consideration.

14 See Sep. Op. of Judge Weeramantry in Genocide Convention #2, suggesting the “highest standards of caution … for making a provisional assessment of interim measures.” (At. p. 371); Sep. Op. of Judge Shahabudeen in id., calling for “substantial credibility” (at p.360). He quotes Dumwald, I.M., Interim Measures of Protection in International Controversies (1933), p.161.Google Scholar That author also notes that in view of the summary nature of the proceeding the rules of evidence should be relaxed. Elsewhere Dumwald argues “[I]t is not necessary that the measures should be absolutely indispensable; it is sufficient if they serve as a safeguard against substantial and not easily reparable injury. The degree of necessity varies with the nature of the measure.” (At p. 163). Previous to the Genocide #2 Case case, in the Great Belt Case, the ICJ stated that evidence had not been adduced of any invitation to tender which could affect Finnish shipyards at a later date, nor “had it been shown” that the shipyards had suffered a decline in orders. Proof of damage had not been supplied (at pp. 18-19, ¶ 29). However, in his Separate Opinion in that case, Judge Shahabudeen, quoting Judge Anzilotti in the Polish Agrarian Reform & German Minority Case, P.C.I.J. Ser. A/B, No. 58, 1933, p. 175 at p. 181, urged that a state requiring interim measures of protection was “required to establish the possible existence of the rights sought to be protected.” (at pp. 34, 36). For useful recent doctrinal views, see Collins, pp. 177-81; Merrills, J.G., “Interim Measures of Protection in the Recent Jurisprudence of the International Court of Justice,” 44 I.C.L.Q. (1995), pp. 90–146, at pp. 114-16.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

15 Art. 83(2) of the Rules of Procedure of the Court of Justice of the European Communities requires the “establishment ofprima facie case for the interim measures applied for.” See Sztucki, p. 6.

16 Art. 90:1 assigns priority of prescription proceedings over all others, subject to art. 112:1 (simultaneous provisional measures and prompt release proceedings — Tribunal to ensure that both are dealt with without delay) art. 90:1); art. 91:2 requires “the earliest” date for the hearing to be set and authorizes the President to call upon the parties to act in such a way as will enable any order of the Tribunal to have appropriate effects.

17 See United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 - A Commentary, Vol. V, 1989 (Myron H. Nordquist, ed-in-chief, with Shabtai Rosenne and Louis B. Sohn, volume editors), p. 56. The legislative history of art. 290:5 is clear, although the language of the article lacks complete clarity.

18 See generally Merrills 1994, pp. 111-13.

19 Circumstances: See e.g. Case Concerning Military and Paramilitary Activities in and Against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. the United States of America)(Provisional Measures), Order of 10 May 1984, ICJ Reports 1984 (hereafter Military & Paramilitary Activities Case), p. 180, ¶ 27; Aegean Sea Continental Shelf Case (Interim Protection), Order of 11 September 1976, ICJ Reports 1976 (hereafter Aegean Sea Case) p. 11, ¶ 32; Elkind, p. 258. Object: Land & Maritime Boundary Case, p. 23, ¶ 42; Genocide Convention #2, p. 342, ¶ 35; Great Belt Case, p. 16, ¶ 16; Case Concerning the Frontier Dispute (Burkina Faso v. Republic of Mali (Provisional Measures), Order of 10 January 1986, ICJ Reports 1986 (hereafter Frontier Dispute Case), p. 10, ¶ 21. Purposes: e.g. H.W.A. Thirlway, “The Indication of Provisional Measures by the International Court of Justice,” in Rudolf Bernhardt (ed.), Interim Measures Indicated by International Courts (1994), pp 1-36, at pp. 5-16. Criteria: e.g. Merrills 1995, pp. 106-25; Grieg, D.W., “The Balancing of Rights and the Granting of Interim Protection by the International Court of Justice,” 11 Austr. Y.B.Int'l L. (1991), pp. 108–40Google Scholar, at p. 123. Intention: e.g. Diss. Op. by Judge ad hoc Thierry in Case Concerning the Arbitral Award of 31 July 1989 (Guinea Bissau v. Senegal) (Request for the Indication of Provisional Measures), Order of 2 March 1990, ICJ Reports 1990, p. 82.

20 Thirlway 1994, at pp. 7-8, suggesting that “infringement” might be more realistic and that it is probably also realistic to talk about the possible imminent disappearance of the right or that the subject matter of the right was going to vanish totally.

21 As will be seen, to the formula the Court has added amplificatory language.

22 Writing in 1933, Dumwald, not appearing to reach as far as implied in the text, said: “The nature or content of the right is immaterial, except that it must be actionable in law and its violation irreparable in money.” Dumwald p. 165.

23 See Sztucki, p. 92, noting that only reasons, consequences and measures must be specified in the Application for measures, indicating “the lack of excessive formalism in entertaining requests for interim measures.” This is presumably relevant to the point under discussion.

24 Provisional measures are ex hypothesi indicated before it is known what the respective rights of the parties are. H.W.A. Thirlway, Non- Appearance Before the International Court of Justice (1985), p. 84. Note the Separate Opinion of Judges Amoun, Foster and Arechaga in the Fisheries Jurisdiction Case (Federal Republic of Germany v. Iceland) (Interim Protection), Order of 17 August 1972, ICJ Reports 1972 (hereinafter Fisheries - F.R.G., Case), p.36 and Fisheries Jurisdiction Case (United Kingdom v. Iceland) (Interim Protection), Order of 17 August 1972, ICJ Reports 1972 (hereafter Fisheries - U.K. Case), p. 18. Therein they note that the Judges’ Order “cannot have the slightest implication as to the validity or otherwise of the rights protected by the Order or of the rights claimed by a coastal State.“

25 This approach is strongly supported by the Nuclear Test Cases, where the ICJ recognized what was referred to in the Orders as a “legal interest” thought to be controversial in international law and relations. ICJ Reports 1973, p. 140, ¶ 24 and p. ¶ 23. See Sztucki, pp. 92-9 and 101 and Merrills 1977, p. 162. Note also U.S. Staff Case, where the ICJ, in a few words, makes the barest mention of rights, (“continuance of the situation … exposes the human beings to privation, hardship, anguish and even danger to life and health and thus to a serious possibility of irreparable harm …“), immediately thereafter discussing injury. ICJ Rep 1979, p. 20, ¶ 42. In the Military & Paramilitary Case, on the other hand, the rights are set forth at some length (p. 169, ¶ 23): rights to “life, liberty and security [of Nicaraguan citizens]; … be free … from the use or threat of force [against Nicaragua] …; to conduct its affairs … [by Nicaragua]; of self-determination [by Nicaragua]), but the link with interim protection is “rather disappointing.” Thirlway 1994, p. 9. This criticism might be misplaced.

26 See generally Dumwald, pp. 175-76.

27 Cases in which orders were made include: Land & Maritime Boundary Case, Frontier Dispute Case; Military & Paramilitary Case; U.S. Staff Case; Nuclear Test Cases. An instructive case in which no order was made is the Case Concerning Questions of Interpretation and Application of the 1971 Montreal Convention arising from the Areal Incident at Lockerbie (Libyan Arab Jamahiriya v. United States) (Provisional Measures), Order of 14 April 1992, ICJ Reports 1992 (hereafter Lockerbie Case).

28 Cases in which orders were made include: Genocide #1 Case; Genocide #2 Case; U.S. Staff Case; probably the Nuclear Test Cases; Sino- Belgian Treaty Case (Belgium v. China), P.C.I.J. Ser. A No. 8 1927, (hereafter Sino-Belgian Case).

29 Cases in which orders were made include: U.S. Staff Case; Fisheries Cases; Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. Case; The Electricity Company of Sofia and Bulgaria (Request for the Indication of Interim Measures of Protection), Order of 5 December 1939, PCIJ, Ser. A/B/ No. 79 (hereafter Electricity Co of Sofia Case). Instructive Cases in which no order was made include: Great Belt Case; Interhandel Case (Interim Protection), Order of 24 October 1972, ICJ Reports 1972 (hereafter Interhandel Case).

30 Case in which orders were made: Nuclear Test Cases. Instructive cases in which no order was made include: Great Belt Case; Aegean Sea Case. See Elkind, p. 223. UNCLOS art. 290:1, dealing with prevention of serious harm to the marine environment, now clearly reinforces this trend.

31 Contained in Parts XI, Section 5, and XV and Annexes V-VIII.

32 These include ship and crew detention; ship nationality; exercise of jurisdiction over ships by non-flag States; marine research; enforcement of domestic pollution laws against individual vessels; deep seabed mining— technical, contractual and commercial issues.

33 Dealing with sovereign rights with respect to the living resources in the EEZ or their exercise.

34 Generally providing for disputes concerning interpretation or application of the Convention with regard to the exercise by a coastal State of its sovereign rights or jurisdiction is subject to the Convention's general compulsory procedures (including submission to this Tribunal) for dispute settlement entailing binding decisions.

35 It would have the same impact on Article 292, on the prompt release, and such related provisions as arts. 73, 220:7 and 226:l(b). In this case, it will also be noted that Respondent, while invoking art. 297:3(a), failed to proceed against the defendant in its own courts under legislation dealing with its sovereign entitlements relating to EEZ living resources, instead proceeding under its customs, marine and related legislation.

36 Dumwald suggests that “The more serious the hardship to defendant, the stricter the scrutiny of plaintiffs wants.” (p. 163). The balancing requirement is often referred to in the common law domestic context as the “balance of convenience.” See 24 Halsbury's Laws of England (4th ed., reissue, 1991), ¶ 856, citing American Cynamid Co. v. Ethicon [1975] AC 396 at p. 408. 1 All ER 504 at p. 510 (House of Lords, Lord Diplock); I.C.F. Spry, The Principles of Equitable Remedies (4th ed, 1990), pp. 454, 462. 465; 42 American Jurisprudence (2d ed., 1969-1997), ¶¶ 56-7.

37 Emphasis added.

38 Provisional measures proceedings are not, in any way, a form of actiopopularis.

39 Great Belt Case, p. 18, ¶ 27. For an earlier discussion, see Sztucki, pp. 115-16, suggesting that the Interhandel Case was decided on that basis. See Interhandel Case, p. 112. There, the judicial proceeding in question was actually before a domestic body, not the international provisional measures proceedings. Thirlway (pp. 25-7) treats urgency as a “condition” for ICJ provisional measures, the other two conditions being the existence of jurisdiction and the existence of prima facie jurisdiction. It has been pointed out that in the jurisprudence of the ICJ, considerable attention has been given to urgency since the Case Concerning the Pakistani Prisoners of War (Pakistan v. India) (Request for the Indication of Interim Measures of Protection), Order of 13 July 1973, ICJ Reports 1993, p. 328, where the case was dismissed on those grounds after Applicant requested postponement. Thirlway 1994, pp. 16-27. See also Land & Maritime Boundary Case, p. 22, ¶ 35. which merely states that “provisional measures are only justified if there is urgency …” Note the analysis in Merrills 1995, pp. 111-13.

40 42 American Jurisprudence, ¶ 26. However, urgency is not a universal rule in various American jurisdictions.

41 See Sztucki, pp. 104-08. As Grieg argues, there is no need to consider urgency where rights had already been infringed, as in some aspects of this case, only where they are threatened, as has been alleged with other aspects of this case. Grieg, p. 136. Note his argument that it “is far from certain that it follows ineluctably from article 74 of the [ICJ's] Rules of Procedure (the counterpart of art. 90 of this Tribunal's Rules), that urgency is an essential and defined quality. He concludes that it has a direct bearing on the need to protect interests and can enhance irreparability. Grieg, p. 137.

42 E.g. the value sought to be protected by the second leg of art. 290:1 — threat of serious harm to the marine environment.

43 See Sztucki, p.p. 112-19, esp. 113. I repeat that it is self-evident that urgency might be dictated by the circumstances. And the operational context of a system of provisional measures might have a significant dimension of urgency. E.g., art. 63(2) of the American Convention on Human Rights, in the more suitable context of human rights, provides that the Inter-American Court of Human Rights may take provisional measures “in cases of extreme gravity and urgency …” See 9 I.L.M. (1970), p. 118.

44 In his analysis of his suggested (apparently substantive) urgency requirement, Thirlway discusses mainly procedural requirements, such as court scheduling.

45 Understandably, art. 63(2) of the American Convention on Human Rights (authorizing the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to adopt provisional measures) refers exclusively to irreparable damage. The concept of irreparability is generally accepted in the doctrine. However, the wrong done or anticipated is described variously. See Merrills 1995, p. 106 (irreparable damage), Elkind, p. 258 (irreparable injury), Grieg, p. 123 (irreparable harm). A leading law dictionary defines each of “injury,” “damage” and “harm” mainly by citing one or both of the other words as a synonym. However, “prejudice” is defined as a “forejudgment; bias; partiality; preconceived opinion.” Only the expression “without prejudice” includes the notion of non-waiver or non-loss of rights or privileges. Black's Law Dictionary pp. 389, 718, 785-86, 1179. Writers often imply that this is not a category, which is separate from prejudice of rights. However, Grieg lists irreparable harm and prejudice of rights as separate categories, not as paraphrase and principle category.

46 The Court seems to have focused on the reparability of prejudice to the Applicant's real or corporeal rights. At the same time, it declined to acknowledge the existence or irreparability of rights of national policy-determination or -formulation. Direct application of the preservation genus, along with a sensitive rendering of the concept of rights, might have induced a different result by the Court.

47 Elkind, p. 223.

48 Sztucki notes the “gravity” of irreparability. See Sztucki, p. 14.

49 See Separate Opinion of Judge Weeramantry in Genocide Convention #2 Case, p. 379.

50 Elkind suggests the category of the intolerableness of the continuance of the situation that complaining party cannot reasonably be expected to endure the status quo pending settlement. Elkind, p. 230.

51 See Separate Opinion by Judge Weeramantry in Genocide Convention #2 Case, p. 379.

52 Such as the Land & Maritime Frontier Case, p. 18, ¶ 19.

53 Sztucki, p. 74, Merrills 1995, pp. 123-24.

54 See, e.g., Dissenting Opinion of Judge Ad Hoc Thierry in Arbitral Award Case, p. 84, and the Lockerbie Case, pp. 180-81; Dissenting Opinion of Judge Ajibola in id., pp. 193-98.

55 Sztucki, p. 74, referring in particular to the ICJ's abstention, on the ground of absence of necessity, from deciding this point in the Aegean Sea Case, pp. 11-13, ¶¶ 34-42 (attention to the problem being simultaneously given by the political organs of the United Nations) and criticisms thereof by Judges Lachs, pp. 20-21 and Elias, pp. 27-28.

56 See Land & Maritime Boundary, p. 22, ¶ 41; Frontier Dispute Case, p. 9, ¶ 18.

57 It will be recalled that art. 290:1 provides that the court or tribunal may prescribe such measures as it consider appropriate …” (emphasis added). This implies that, as long as a party has requested provisional measures, the Tribunal has power to order appropriate measures. Article 89:5 of the Rules of the Tribunal, like Art. 75:2 of the ICJ Rules, provides for the Tribunal (on its own) to prescribe measures different in whole or in part from those requested. The significance of the Tribunal's discretionary power in this area will be recalled.

58 It is conceded that in cases involving private parties or largely commercial or technical matters (unlike the present case), questions might be asked about the desirability of routinely prescribing non-aggravation or non-extension measures.

59 Additional to the alleged main categories of irreparable prejudice and urgency. Sztucki, pp. 123 and 127-29.

60 See Merrills 1995, pp. 106-25 (a “criterion”, Elkind, p. 230 (a “category” which applies “generally“), Grieg, p. 123 (a “criterion“).

61 One notable exception is Elkind, apparently influenced by the Nuclear Test Cases and making mention of the provision in the draft of what became art. 290:1. See Elkind, pp. 220-24.

62 See Elkind, p. 230, who seems to include environmental protection under his second, of three, “categories,” viz. “where the continuance of a situation is intolerable and the complaining party cannot reasonably be expected to endure the status quo pending judicial settlement of a dispute.“

63 Some of these more or less frequently may be manifested in such component paradigms as those suggested by Judge Weeramantry.

64 The same approach is suitable for the irreparability formulation, if the Tribunal, after careful deliberation, occasionally decides to rely on that grave tool in some specific cases.

* ILO Conventions Nos. 29 and 105 on forced labor, 87 and 98 on freedom of association and collective bargaining, 100 and 111 on discrimination, and 138 on child labor. It is expected that in June 1999 a new Convention will be adopted on the “worst forms” of child labour.

** Developments in this area can be followed on the ILO's web site at http://www.ilo.org.