No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

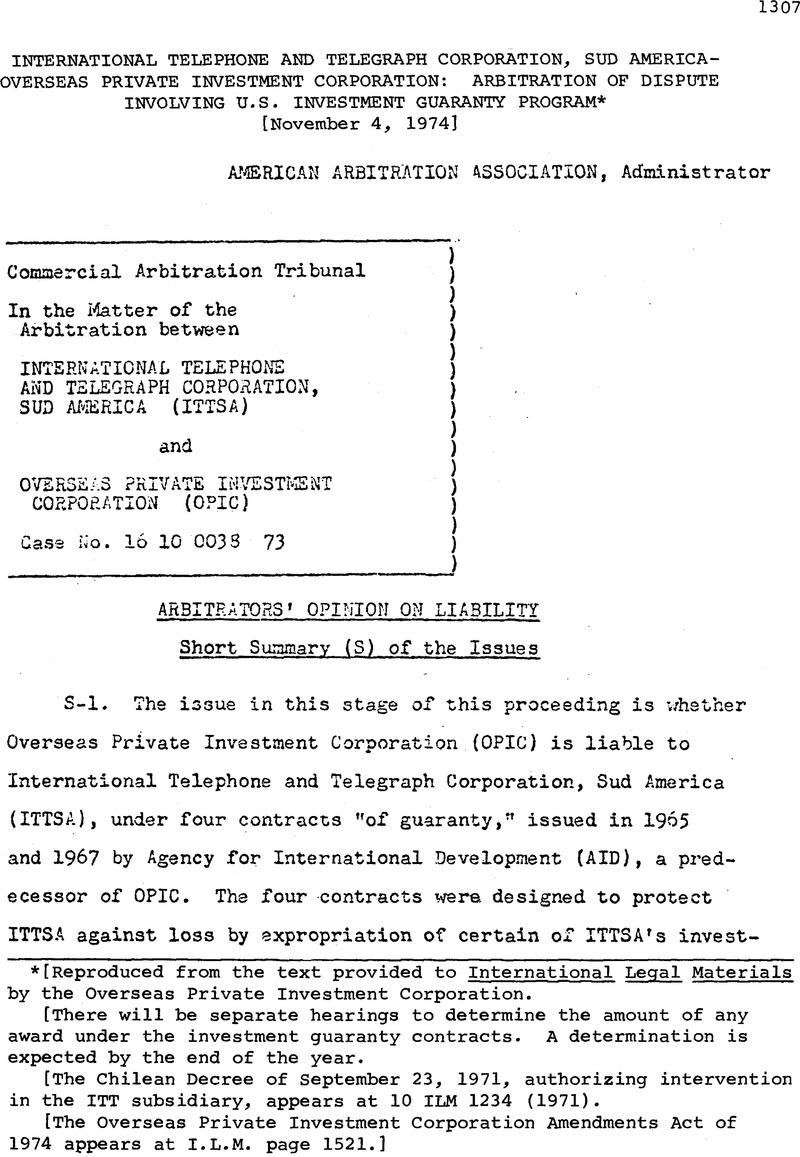

[Reproduced from the text provided to International Legal Materials by the Overseas Private Investment Corporation.

[There will be separate hearings to determine the amount of any award under the investment guaranty contracts. A determination is expected by the end of the year.

[The Chilean Decree of September 23, 1971, authorizing intervention in the ITT subsidiary, appears at 10 ILM 1234 (1971).

[The Overseas Private Investment Corporation Amendments Act of 1974 appears at I.L.M. page 1521.]

1 “Tr.” refers to the transcript in this matter. “CH.” refers to the pages of the Church bearings (1973), before the Subcommittee on Multinational Corporations, Committee on Foreign Relations, U. S. Senate {ITT and Chile). Exhibits with no prefix to the number were introduced by ITTSA. Exhibits with the prefix “O-” were introduced by OPIC. Paragraphs of this suramary are preceded by the prefix “S-.” Following this summary, the consecutively numbered paragraphs have no prefix.

2 At September 29, 1971 (the intervention date) the book value of ITT3A’s investment in CT Co. was about $153,000,000. See Tr. 432, 443, 472; Ex. 26. ITTSA thus was-a self-insurer for an amount about or above $50 milliorv.

3 Subsection (c) of § 402 lists among factors affecting investment in underdeveloped areas not only “confidence on the part of the people of the underdeveloped areas that investors will conserve as well as develop local resources, will bear a fair share of local taxes and observe local laws, and will provide adequate wages and working conditions for local labor,” but also “confidence on the part of investors, through intergovernmental agreements or otherwise, that they will not be deprived of their property without prompt, adequate, and effective compensation; that they will be given reasonable opportunity to remit their earnings and withdraw their capital; that they will have reasonable freedom to manage, operate, and control their enterprises; that they will enjoy security in the protection of their persons and property, including industrial and intellectual property, and nondiscriminatory treatment in taxation and in the conduct of their business affairs.” See Sen. Doc. No. 142, 8lst Cong. 2d Sess. 8–11 (1950).

4 Previously, the program had been administered successively by the European Cooperation Administration from 1943 to 1951, by the Mutual Security Agency from 1951 to 1953, the Foreign Operations Administration from 1953 to 1955, and the International Cooperation Administration from 1955 to 1961. OPIC brief, p. 4.

5 See e.g. Hearings on H. R. 7372 and K. R. 8400, House Committee on Foreign Affairs, 87th Cong. 1st Sess. 323-324 (1961), H. R. Rep. No. 1788, 87th Cong. 2d Sess. pp. 28-11 (1962); H. R. Rep. No. 1271, 90th Cong. 2d Sess. 28-35 (1968), on the involvement of U. S. private enterprise in developing countries. For reservations about this policy and possible foreign hostility to it, based on fears of continued “colonialism,” see Clubb and Vance, “Incentive to U. S. Investment Abroad under the Foreign Assistance Program,” 72 Yale L. J. 475-478-, but see 487-500 (1963); Marina von N. Whitman, The United States Investment Guaranty Program and Private Foreign Investment, 9 et seq., 13 et seq., 20 et seq., 38 et seq., 65 et seq., 76 et seq.

(Princeton 1959). See also Mira Wilkins, The Maturine of Multinational Enterprise, 328–337 (Harv. Univ. Press, 1974); Tondel, Role of Private Investors in U. S. Foreign. Aid, in 1964 Symposium on Rights and Duties of Private Investment Abroad, The South-western Legal Foundation. 1965, 309, 324-326; Chayes, U. S. Policy Toward Private Investment Abroad, ibid. 345 et seq.; Fatouras, Government Guarantees to Foreign Investors (Columbia Univ. Press, 1962), a general discussion of the guaranty problem; Ray, Evolution, Scope and Utilization of Guarantees of Foreign Investcents, 21 Bus. Lawyer, 1051, 1054 et seq. (1966).

6 Subsequent references in this paragraph 8 are to sections of the 1970 edition of the U. S. Code.

7 Excluded from “expropristory action,” (among other matters) are certain types of action or events set out in language quoted from § 1.15 of the contracts. See fn. 14 to par. 81, infra.

7a OPIC in its posthearing brief, p. 30, concedes that the possibility of CT Co.’s securing a rate increase “was generally agreed to be non-existent.”

8 In the report of the Church Committee hearings, there appears a large volume of ITT internal communications showing concern about the Chilean situation during much of the period from October, 1970, through the whole of 1971. (CH. 731-622, 831-834, 838-852, 856-864, 867-898, 954-1005) This material (e.g. CH 964, 975) may reveal somewhat increasing State Department interest in expropriation matters. The evidence in this case, however, does not show what, if any, U. S. Government action took place as,a consequence of any ITT activities.

9 OPIC is not shown to have told ITTSA’s representatives directly that they were under any contractual obligation to negotiate, although OPIC’s president testified that it was, in his opinion, a duty recognized and accepted by ITTSA. See Tr. 1027, 1049 et seq. Ex. 0-107; 0-113, at bottom of 14th page and top of 15th page of application attached to or enclosed with Guilfoyle’s letter of October 7, 1971, to President Mills of OPIC.

9a For example, the provision might have reference to (a) seasonable application, under generally established procedures, for damages from an eminent domain taking within the statutory period available, or (b) seeking seasonably relief under such procedures against a confiscatory tax.

* See, for example OPIC’s Annual Report for 1971, which stated (Ex. 8): “On September 29, 1971, the Government of Chile intervened in the Chile Telephone Company in which… [ITT] holds a majority interest. This is insured by OPIC in the current amount of $108,500,000” (emphasis supplied). See also Tr. 919, 921, 931, 1077-1078, 1086, 1163, 1115, 1128; 0-53, 0-103A, 7; 22 U. S. Code (1970), §§ 2194 (a), 2197.

11 The State Department, Dr. Kissinger’s office (White House), the U.S.I.S. and CIA were the U. S. agencies concerned. See pars. 37-49, supra. CIA’s refusal to accept a financial contribution was consistent with the earlier policy of CIA. Tr. 719. CIA is not shown, expressly or impliedly, to have suggested to ITTSA that ITTSA’s discussions with it were improper. Indeed it kept in touch with ITTSA. See par. 41, supra. See as to offers of support of an overt program, Tr. 722. See as to the State Department’s apparent disregard of the offer made to Dr. Kissinger, Tr. 719. OPIC’s president never told other insured expropriated companies or ITTSA that they were debarred from talking with the U. S. Government or that their membership in the ad hoc committee (par. 44, supra), or their failure to disclose that membership, constituted a breach of their-insurance contracts. Tr. 1014-1027, esp. at 1022.

12 The policy urged upon the U. S. government was, in some degree at least, consistent with the statement of policy in the 1961 statute (see par. 6, supra) which, among other declarations, reaffirmed the “conviction” of Congress (see Pub. L. 87-195, § 102; 75 Stat. 424, 425) “that the peace of the world and the security of the United States are endangered so long as international coamunism continues to attempt to bring under Communist domination peoples now free and independent… This in § 102 was one reason expressed for the social and economic foreign assistance offered by the 1961 statute.

13 We regard it as unnecessary to decide what ITTSA’s just claim to compensation against GOG under international law may have been because the issues before us concern only ITTSA’s claims against OPIC under the four contracts. The Restatement sections cited in the text state the doctrines of compensation long espoused by the United States.

* Section 3.02 (as it appears in a slightly expanded form in Contracts Nos. 5773 and 5925 (cf. the language above as it appears in Contracts Nos. 5369, 5370) makes it also a “curable breach” during the time “while a claim is pending for… compensation hereunder,” if the “Investor shall have knowingly failed to make any disclosure to AID significant to the nature either of the Project or the Investment or material to the claim” (new or changed words emphasized).

14 It is also provided in § 1.15 that “no such action shall be deemed an Expropriatory Action if it occurs, or continues in effect during the aforesaid period, as a result of:

(1) any law, decree, regulation, or administrative determination of the Government of the Project Country which is reasonably related to its constitutionally sanctioned governmental objectives, is not by its express terms for the purpose of nationalization, confiscation, or expropriation, is neither arbitrary nor discriminatory, and does not violate generally accepted international law principles; or …

insolvency of or creditors’ proceedings against the Foreign Enterprise other than an insolvency or a creditors’ proceeding directly resulting from acts of the Foreign Enterprise which could have been restrained under applicable law and which the Investor attempted to restrain but was prevented from doing so for a period of one year by action taken, authorized, ratified or condoned by the Government of the Project Country during the Guaranty Period.”

15 The term “Net Investment” with respect to debt is defined in § 1.23, in part as follows: “The terra ‘Net Investment’ means, any date,…(i) the principal then outstanding and the interest then accrued and unpaid in connection with the Investment [see § 1.22] contributed by the Investor for the debt Securities owned, Free and Clear, by the Investor on such date, and (ii)” the equity investment less the return on capital if any (emphasis supplied). “Investment” is defined in § 1.22 as “the Investor’s contribution to the Foreign Enterprise at the United States dollar value thereof on each Date of Investment…. Where the constituent elements are other than cash, the value thereof shall be the lesser of the value agreed upon between the Investor and the Foreign Enterprise and a reasonabis value in the United States of America for such elements (normally the fair market value) in accordance with principles of valuation generally accepted in the United States of America. To the extent that the Investor is bearing the costs of freight, insurance, import duties, costs of installation and related costs, such costs may be added to the reasonable value in valuing the Investment.” See 73 (b), supra.