Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

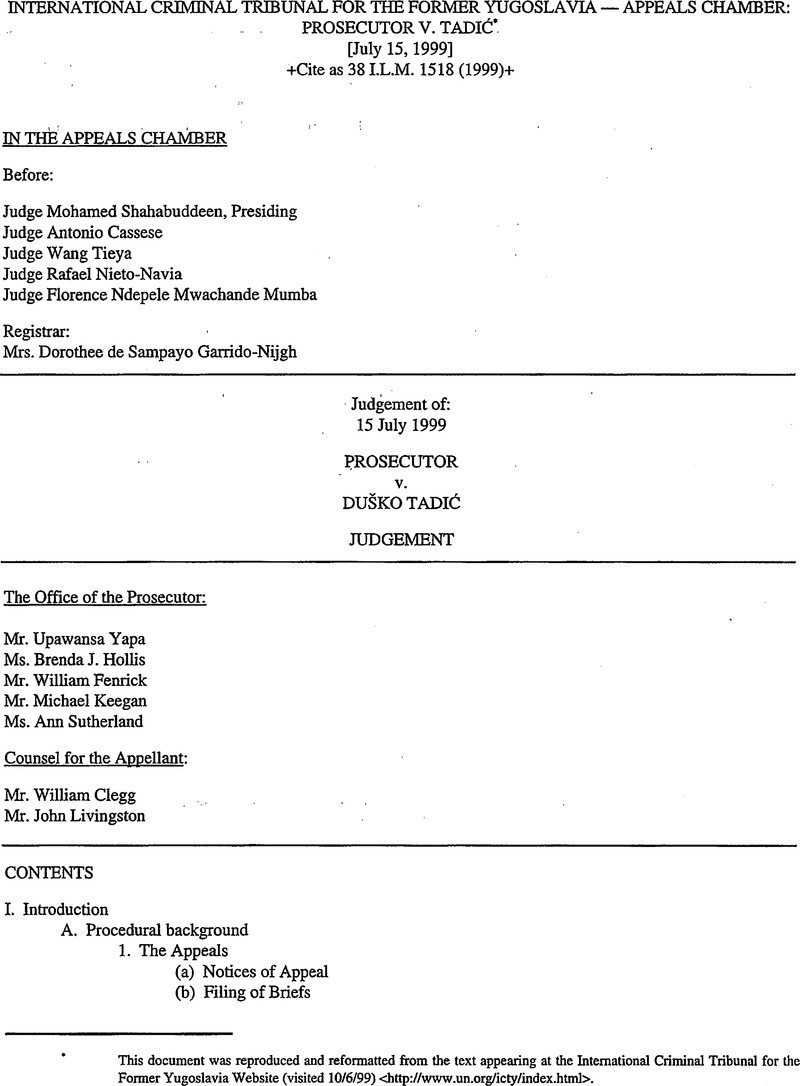

This document was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia Website (Visited 10/6/99) <http://www.un.org/icty/index.html>.

1 Composed of Judge Gabrielle Kirk McDonald (Presiding), Judge Ninian Stephen and Judge Lai Chand Vohrah.

2 “Opinion and Judgment”, The Prosecutor v. Duško Tadić, Case No.: IT-94-1-T, Trial Chamber JJ, 7 May 1997. (For a list of designations and abbreviations used in this Judgement, see Annex A — Glossary of Terms).

3 “Sentencing Judgment”, The Prosecutor v. Duško Tadić, Case No.: IT-94-1-T, Trial Chamber JJ, 14 July 1997.

4 “Judgement”, The Prosecutor v. Dražen Erdemović, Case No.: JT-96-22-A, Appeals Chamber, 7 October 1997.

5 It should be observed that Duško Tadić in the present proceedings is appellant and cross-respondent. Conversely, the Prosecutor is respondent and cross-appellant. In the interest of clarity of presentation, however, the designations “Defence” or “Appellant” and “Prosecution“ or “Cross-Appellant” will be employed throughout this Judgement.

6 “Amended Notice of Appeal”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 8 January 1999.

7 Transcript of hearing in The Prosecutor v Duško Tadić, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 25 January 1999, p. 307 (T. 307 (25 January 1999). (All transcript page numbers referred to in the course of this Judgement are from the unofficial, uncorrected version of the English transcript. Minor differences may therefore exist between the pagination therein and that of the final English transcript released to the public).

8 ‘'Notice of Appeal”, Case No.: JT-94-1-A, 6 June 1997

9 “Motion for the Extension of the Time Limit”, Case No.: JT-94-1-A, 6 October 1997.

10 T.105 (22 January 1998).

11 “Decision on Appellant's Motion for the Extension of the Time-limit and Admission of Additional Evidence”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 15 October 1998.

12 “Appellants Brief on Appeal Against Opinion and Judgement of 7 May 1997”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 12 January 1998, with accompanying appendices separately filed; “Appellant's Brief on Appeal Against Sentencing Judgement” Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 12 January 1998.

13 “Cross-Appellant's Response to Appellant's Brief on Appeal against Opinion and Judgement of May 7,1997,Filedon 12January 1998”, Case No.: JT-94-1-A, 17 November 1998; “Response to Appellant's Brief on Appeal Against Sentencing Judgement filed on 12 January 1998”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 16 November 1998.

14 “Amended Brief of Argument on behalf of the Appellant”, Case No.: JT-94-1-A, 8 January 1999.

15 T. 308 (25 January 1999).

16 “Brief of Argument of the Prosecution (Cross-Appellant)”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 12 January 1998 and accompanying “Book of Authorities”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 22 January 1998. (See also “Corrigendum to Prosecutor's Brief of Argument filed on 12 January 1998 and Book of Authorities filed on 22 January 1998” Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 9 September 1998).

17 “The Respondent's Brief of Argument on the Brief of Argument of the Prosecution (Cross-Appellant) of January 12,1998”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 24 July 1998.

18 “Prosecution (Cross-Appellant) Brief in Reply”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 1 December 1998.

19 “The Respondent's Brief of Argument on the Brief of Argument of the Prosecution (Cross-Appellant) of January 19,1999”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 19 January 1999.

20 “Order Accepting Filing of Substitute Brief, Case TT-94-1-A, 4 March 1999. (See also “Opposition to the Appellant's 19 January 1999 filing entitled “The Respondent's Brief of Argument on the Brief of Argument of the Prosecution (Cross-Appellant) of 19 January, 1999 (sic)'”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 21 January 1999; “Submission in relation to Appellant's ‘Substitute Brief filed on 19 January 1999”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 24 February 1999).

21 “Skeleton Argument — Appellant's Appeal Against Conviction”,.Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 19 March 1999 (“Skeleton Argument — Appellant's Appeal Against Conviction“); “Skeleton Argument—Appeal Against Sentence”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 19 March 1999; “Skeleton Argument of the Prosecution”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 19 March 1999 (“Skeleton Argument of the Prosecution“). See also “Skeleton Argument —Prosecutor's Cross-Appeal”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, originally filed by the Defence on 19 March 1999 and subsequently re-filed on 20 April 1999 (“Defence's Skeleton Argument on the Cross-Appeal“).

22 “Motion for the Extension of the Time Limit”, Case No.: IT-94-l-A, 6 October 1997.

23 Rule 115 provides:

“(A) A party may apply by motion to present before the Appeals Chamber additional evidence which was not available to it at the trial. Such motion must be served on the other party and filed with the Registrar not less than fifteen days before the date of the hearing. (B) The Appeals Chamber shall authorise the presentation of such evidence if it considers that the interests of justice so require.”

24 Rule 119 provides:

“Where a new fact has been discovered which was not known to the moving party at the time of the proceedings before a Trial Chamber or the Appeals Chamber, and could not have been discovered through the exercise of due diligence, the defence or, within one year after the final judgement has been pronounced, the Prosecutor, may make a motion to that Chamber for review of the judgement.”

25 “Motion to Extend the Time Limit”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 10 September 1997; “Motion for the Extension of the Time Limit“ (Confidential), Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 6 October 1997; “The Motion for the Extension of Time”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 17 March 1998; “Application for Extension of Time to File Additional Evidence on Appeal”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 1 May 1998; “Motion for Extension of Time to File Reply to Cross-Appellant's Response to Appellant's Submissions since 9th March 1998 on the Motion for the Presentation of Additional Evidence under Rule 115”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 15 June 1998; “Request for an Extension of Time to File a Reply to the Appellant's Motion Entitled ‘Motion for the Extension of the Time Limit“1, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 9 October 1997; “Request for a Modification of the Appeals Chamber Order of 22 January 1998”, Case No.: 1T-94-1-A, 13 February 1998; “Request for a Modification of the Appeals Chamber Order of 2 February 1998”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 7 May 1998. The following orders were made in relation to these applications: “Scheduling Order”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 24 November 1997; “Order Granting Request for Extension of Time”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 23 March 1998; “Order Granting Requests for Extension of Time”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 13 May 1998; “Order Granting Extension of Time”, Case No.: 1T-94-1-A, 10 June 1998; “Order Granting Extension of Time”, Case No.: JT-94-1-A, 17 June 1998; “Order Granting Request for Extension of Time“,.Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 9 October 1997; “Order Granting Request for Extension of Time”, Case No.: JT-94-1-A, 19 February 1998; “Order Granting requests for Extension of Time”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 13 May 1998.

26 “Decision on Appellant's Motion for the Extension of the Time-limit and Admission of Additional Evidence”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 15 October 1998.

27 “Appellant's Second Motion to Admit Additional Evidence on Appeal Pursuant to Rule 115 of the Tribunal's Rules”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 8 January 1999; “Motion (3) to Admit Additional Evidence on Appeal Pursuant to Rule 115 of the Rules of Procedure and Evidence”, Case No.: IT-94-1,19 April 1999.

28 T.307-308 (25 January 1999); T. 20 (19 April 1999).

29 See “Scheduling Order Concerning Allegations against Prior Counsel”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 10 February 1999. At the outset of the appellate process, Mr. Milan Vujin acted as lead counsel for the Defence, with the assistance of Mr. R. J. Livingston. By a decision of the Deputy Registrar on 19 November 1998, Mr. Milan Vujin was withdrawn as counsel for the accused and replaced by Mr. William Clegg as lead counsel (See “Decision of Deputy Registrar regarding the Assignment of Counsel and the Withdrawal of Lead Counsel for the Accused”, Case No.: IT-94-1-A, 19 November 1998).

30 Appellant's Amended Notice of Appeal against Judgement, paras. 1.1-1.4; Appellant's Amended Brief on Judgement, paras. 1.1-1.12.

31 Appellant's Amended Notice of Appeal against Judgement, paras. 3.1-3.6; Appellant's Amended Brief on Judgement, paras. 3.1-3.11.

32 Amended Notice of Appeal, paras. 2.1-2.4.

33 T.307 (25 January 1999).

34 Notice of Cross-Appeal, p. 2; Cross-Appellant's Brief, paras. 2.1-2.88.

35 Notice of Cross-Appeal, p. 2; Cross-Appellant's Brief, paras. 3.1-3.33.

36 Notice of Cross-Appeal, p. 3; Cross-Appellant's Brief, paras. 4.1-4.23.

37 Notice of Cross-Appeal, p. 3; Cross-Appellant's Brief, paras. 5.1-5.28.

38 Notice of Cross-Appeal, p. 3; Cross-Appellant's Brief, paras. 6.1-6.32 with reference to “Decision on Prosecution Motion for Production of Defence Witness Statements”, Case No.: IT-94-1-T, Trial Chamber n, 27 November 1996.

39 T. 306 (21 April 1999).

40 T. 303 (21 April 1999).

41 Appellant's Brief on Sentencing Judgement, pp. 4-6; T. 304(21 April 1999)

42 Appellant's Brief on Sentencing Judgement, pp. 9-10; T. 305 (21 April 1999)

43 Sentencing Judgement, para. 76. See Appellant's Brief on Sentencing Judgement, p. 10.

44 Ibid., p. 14.

45 Appellant's Amended Notice of Appeal against Judgement, p. 3.

46 Notice of Cross-Appeal, p. 3.

47 Ibid.p.4.

48 Ibid.

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid.

51 Appellant's Amended Brief on Judgement, paras. 1.1-1.3; T. pp. 35-40 (19 April 1999).

52 Appellant's Amended Brief on Judgement, para 1.11.

53 Appellant's Amended Notice of Appeal against Judgement, p. 6.

54 Dombo BeheerB.V. v. The Netherlands, Eur. Court H.R.judgement of 27 October 1993, Series A, no. 274; Neumeisterv. Austria, Eur. Court H.R.judgement of 27 June 1968, Series A, no. 8;Delcourt v. Belgium, Eur. Court H.R.judgement of 17 January 1970, Series A, no.11 Borgers v. Belgium, Eur. Court H.R. judgement of 30 October 1991, Series A, no. 214; Albert and Le Compte v. Belgium, Eur. Court H. R. judgement of 10 February 1983, Series A, no. 58; Bendenoun v. France, Eur. Court H. R. judgement of 24 February 1994, Series A, no. 284; Kaufman v. Belgium, Application No. 10938/84,50 Decisions and Reports of the European Commission of Human Rights (“DR“) 98; X and Y v. Austria, Application No. 7909/74,15 DR 160.

55 T. 30-31 (19 April 1999).

56 T. 31 (19 April 1999).

57 Appellant's Amended Brief on Judgement, paras. 1.4-1.6; T. 29-31,40,45-48 (19 April 1999).

58 T. 38-41 (19 April 1999).

59 T. 52-53 (19 April 1999).

60 T. 50-51 (19 April 1999).

61 T. 45-49(19 April 1999).

62 Prosecution's Response to Appellant's Brief on Judgement, paras. 3.8-3.16,3.30.

63 Prosecution's Response to Appellant's Brief on Judgement, paras. 3.21-3.23; T. 88-89 (20 April 1999).

64 T. 90-91 (20 April 1999).

65 T. 97 (20 April 1999).

66 T. 90,98-99 (20 April 1999).

67 Skeleton Argument of the Prosecution, para.10; Prosecution's Response to Appellant's Brief on Judgement, paras. 3.29,6.9.

68 Skeleton Argument of the Prosecution, para. 6.

69 T. 96 (20 April 1999).

70 T. 100 (20 April 1999).

71 Article 14(1) of the ICCPR provides in part: “All persons shall be equal before the courts and tribunals. In the determination of any criminal charge against him, or of his rights and obligations in a suit at law, everyone shall be entitled to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal established by law. […].“

72 Article 6(1) of the ECHR provides in part: “In the determination of his civil rights and obligations or of any criminal charge against him, everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal established by law.“

73 Article 8(1) of the American Convention on Human Rights provides in part:

“Every person has the right to a hearing, with due guarantees and within a reasonable time, by a competent, independent, and impartial tribunal, previously established by law, in the substantiation of any accusation of a criminal nature made against him or for the determination of his rights and obligations of a civil, labour, fiscal or any other nature.”

74 T. 29-35 (19 April 1999).

75 Morael v. France, Communication No. 207/1986,28 July 1989, U.N. Doc. CCPR/8/Add/l, 416.

76 Robinson v. Jamaica, Communication No. 223/1987,30 March 1989, U.N. Doc. CCPR/8/Add.l, 426.

77 Wolfv. Panama, Communication No. 289/1988,26 March 1992, U.N. Doc. CCPR/11/Add.l, 399.

78 T. 29-35 (19 April 1999).

79 Kaufman v. Belgium, 50 DR 98.

80 Ibid., p. 115.

81 Dombo Beheer B.V. v. The Netherlands, Eur. Court H. R. judgement of 27 October 1993, Series A, no. 274.

82 Ibid., para. 40.

83 Delcourt y. Belgium, Eur. Court H. R.judgement of 17 January 1970, Series A, no. 11.

84 Ibid., para. 34

85 In Kaufman v. Belgium, 50 DR 98, the Eur. Commission H. R. held that equality of arms did not give the applicant a right to lodge a counter-memorial. In Neumeister v. Austria, Eur. Court of H. R.judgement-of 27 June 1968, Series A, no. 8, the Court decided that the principle did not apply to the examination of the applicant's request for provisional release, despite the prosecutor having been heard exparte. In Bendenoun v. France, Eur. Court H. R.judgement of 24 February 1994, Series A, no. 284, the Court ruled that an applicant who did not receive a complete file from the tax authorities was not entitled thereto under the principle of equality of arms because he was aware of its contents and gave no reason for the request. In Dombo Beheer B.V. v. The Netherlands, Eur. Court H. R. judgement of 27 October 1993, Series A, no. 274, the Court held that there was a breach of equality of arms where the single first hand witness for the applicant company was barred from testifying whereas the defendant bank's witness was heard.l

86 B.d. Bet al. v. The Netherlands, Communication No. 273/1989,30 March 1989, U.N. Doc. A/44/40,442.

87 Nqalula Mpandanjila et al. v. Zaire, Communication No 138/1983,26 March 1986, U.N. Doc. A/41/40,121.

88 See “Judgement on the Request of the Republic of Croatia for'Review of the Decision of Trial Chamber II of 18 July 1997”, The Prosecutor v. Tihdmir Blaškić Case No.: IT-95-14-AR108W, Appeals Chamber, 29 October 1997, para. 26.

89 Ibid., para. 33

90 T. 47 (19 April 1999); Judgement, para. 32 (“Following a recess of three weeks after the close of the Prosecution case to permit the Defence to make its final preparations, the Defence case opened on 10 September 1996 [… ].“).

91 Judgement, paras. 29-35.

92 T. 59, 60 (20 April 1999).

93 Letter from President Cassese to Mrs. B. Plavsić of 19 September 1996, referred to by Judge Shahabuddeen during the hearing on 20 April 1999 (ibid.).

94 In its submissions, the Defence refers to the victim identified by the Trial Chamber only as one “Osman”, by the name “Osman Didovic”. The Appeals Chamber is not here called upon to determine whether the name thus given by the Defence is accurate.

95 Prosecution's Response to Appellant's Brief on Judgement, para. 2.14.

96 More fully, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Genocide and Other Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of Rwanda and Rwandan Citizens responsible for genocide and other such violations committed in the territory of neighbouring States, between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 1994.

97 Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War of August 12,1949 (“Geneva Convention IV” or “Fourth Geneva Convention“).

98 Military and Paramilitary Activities in and Against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States of America) (Merits), Judgment, ICJ Reports (1986), p. 14 (“Nicaragua“).

99 See Defence's Substituted Response to Cross-Appellant's Brief, para. 2.6.

100 See Defence's Substituted Response to Cross-Appellant's Brief, paras. 2.1 - 2.18; T. 219-220 (21 April 1999).

101 See “Decision on the Defence Motion for Interlocutory Appeal on Jurisdiction”, The Prosecutor v. Duško Tadić, Case No.: IT-94-1-AR72, Appeals Chamber, 2 October 1995 (“Tadić Decision on Jurisdiction“), paras. 79-84 (Tadi6(1995) I ICTY JR 353).

102 See para. 2.25 of the Cross-Appellant's Brief:

“The SFRY/FRY is a Party td an international armed conflict with [… ] BH on the basis that the Trial Chamber found that until 19 May 1992 the JNA was involved in an international armed conflict with the BH, and that thereafter the VJ was directly involved in an armed conflict against the BH. Consequently, it is submitted that the only conclusion that can be drawn is that an international armed conflict existed between the BH and the FRY during 1992.” (emphasis added).

103 See para. 1 of Separate and Dissenting Opinion of Judge McDonald Regarding the Applicability of Article 2 of the Statute, The Prosecutor v. Duško Tadić, Case No.: IT-94-1-T, Trial Chamber II, 7 May 1997 (“Separate and Dissenting Opinion of Judge McDonald“) where she held: “I find that at all times relevant to the Indictment, the armed conflict in opština Prijedor was international in character [… ]”.

104 See Judgement, paras. 569-608:

“569. [… ] [TJt is clear from the evidence before the Trial Chamber that, from the beginning of 1992 until 19 May 1992, a state of international armed conflict existed in at least part of the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This was an armed conflict between the forces of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina on the one hand and those of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro), being the JNA (later the VJ), working with sundry paramilitary and Bosnian Serb forces, on the other. […].

570. For evidence of this it is enough to refer generally to the evidence presented as to the bombardment of Sarajevo, the seat of government of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, in April 1992 by Serb forces, their attack on towns along Bosnia and Herzegovina's border with Serbia on the Drina River and their invasion of south-eastern Herzegovina from Serbia and Montenegro [… ].” (emphasis added).

105 Cross-Appellant's Brief, para. 2.5.

106 See Judgement, paras.'607-608.

107 In addition to the evidence referred to in para. 570 of the Judgement, reference may also be made to the facts cited by Judge Li in his Separate Opinion to the Tadić Decision on Jurisdiction (paras. 17-19), for example BH's Declaration that it was at war with the FRY and the reports of various expert bodies suggesting that the conflict was international. Moreover, in three Rule 61 Decisions involving the conflict between the Serbs and the BH Government (Nikolić, Vukovar Hospital, and Karadzić and Mladić), Trial Chambers have found the conflict to have been an international armed conflict. (See “Review of Indictment Pursuant to Rule 61 of the Rules of Procedure and Evidence”, The Prosecutor v. Dragon Nikolić, Case No.: IT-94-2-R61, Trial Chamber 1,20 October 1995, para 30 (Nikolić, (1995) IIICTY JR 738); “Review of Indictment Pursuant to Rule 61”, The Prosecutor v. Mile Mrkšić et al., Case No.: IT-95-13-R61, Trial Chamber 1,3 April 1996, para. 25; “Review of the Indictments Pursuant to Rule 61 of the Rules Procedure and Evidence”, The Prosecutor v. Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladić, Case No.: IT-95-18-R61, Trial Chamber 1,11 July 1996, para. 88)).

108 Cross-Appellant's Brief, para. 2.31.

109 Ibid., para. 2.30.

110 Ibid.

111 Ibid., paras.2.21-2.23.

112 Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War of August 12,1949 (“Geneva Convention III” or “Third Geneva Convention“).

113 These four conditions are as follows:

(a) that of being commanded by a person responsible for his subordinates;

(b) that of having a fixed distinctive sign recognisable at a distance;

(c) that of carrying arms openly; and

(d) that of conducting their operations in accordance with the laws and customs of war.

It might be contended that these conditions, which undoubtedly had become part of customary international law, may now be considered to have been replaced by the different conditions set out in Article 44(3) and 43(1) of Additional Protocol I (Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Additional Protocol I), 1977). This contention should .of course be premised on the assumption — for which proof is required — that these two Articles have already been transformed into customary international rules.

Be that as it may, the requirement in Article 43(1) of “[being] under a command responsible to [a] party [to the conflict] for the conduct of its subordinates” has not replaced that of “belonging to a Party to the conflict” provided for in Article 4(A)(2) of the Third Geneva Convention. See generally the International Committee of the Red Cross (“ICRC“) Commentary on the Additional Protocols (Yves Sandoz et al. (eds.), Commentary on the Additional Protocols of 8 June 1977 to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva 1987), pp. 506-517, paras. 1659-1681.

114 Jean Pictet (ed.), Commentary: HI Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva, 1960, First reprint, Geneva, 1994, p. 57:

“|T]here should be a de facto relationship between the resistance organization [or militia or volunteer corps] and the party [… ] which is in a state of war, but the existence of this relationship is sufficient It may find expression merely by tacit agreement, if the operations are such as to indicate clearly for which side the resistance organization [or militia or volunteer corps] is fighting”.

115 Military Prosecutor v. Omar Mahmud Kassem et at, 42 International Law Reports 1971, p. 470, at p. 477. The court consequently held that the accused, members of the PLO captured by Israeli forces in the territories occupied by Israel, did not belong to any Party to the conflict. As the court put it (ibid., pp. 477-478):

“In the present case [… n]o Government with which we are in a state of war accepts responsibility for the acts of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. The Organization itself, so far as we know, is not prepared to take orders from the Jordan[ian] Government, witness[ed by] the fact that [the Organization] is illegal in Jordan and has been repeatedly harassed by the Jordan[ian] authorities.”

116 See also the ICRC Commentary to Article 29 of the Fourth Geneva Convention (Jean Pictet (ed.), Commentary: TV Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva, 1958, First Reprint, 1994, p. 212):

“It does not matter whether the person guilty of treatment contrary to the Convention is an agent of the Occupying Power or in the service of the occupied State; what is important is to know where the decision leading to the unlawful act was made, where the intention was formed and the order given. If the unlawful act was committed at the instigation of the Occupying Power, then the Occupying Power is responsible; if, on the other hand, it was the result of a truly independent decision on the part of the local authorities, the Occupying Power cannot be held responsible.”

117 The Appeals Chamber is aware of another approach taken to the question of imputability in the area of international humanitarian law. The Appeals Chamber is referring to the view whereby by virtue of Article 3 of the IV th Hague Convention of 1907 and Article 91 of Additional Protocol I, international humanitarian law establishes a special regime of State responsibility; under this lex specialis States are responsible for all acts committed by their “armed forces” regardless of whether such forces acted as State officials or private persons. In other words, whether or not in an armed conflict individuals act in a private capacity, their acts are attributed to a State if such individuals are part of the “armed forces” of that State. This opinion was authoritatively set forth by some members of the International Law Commission (“JJLC“) (Professor Reuter observed that “[i]t was now a principle of codified international law that States were responsible for all acts of their armed forces” (yearbook of the International Law Commission, 1975,vol. I, p.7, para. 5). Professor Ago stated that the IV thHague Convention of 1907 “made provision for a veritable guarantee covering all damage that might be caused by armed forces, whether they had acted as organs or as private persons” (ibid., p. 16, para.4)). This view also has been forcefully advocated in the legal literature.

As is clear from the reasoning the Appeals Chamber sets out further on in the text of this Judgement, even if this approach is adopted, the test of control as delineated by this Chamber remains indispensable for determining when individuals who, formally speaking, are not military officials of a State may nevertheless be regarded as forming part of the armed forces of such a State.

118 Nicaragua, para. 115. As the Court put it, there must be “effective control of the military or paramilitary operations in the course of which the alleged violations [of international human rights and humanitarian law] were committed”.

119 Ibid., para. 115:

“All the forms of United States participation mentioned above, and even the general control by the respondent State over a force with a high degree of dependency on it, would not in themselves mean, without further evidence, that the United States directed or enforced the perpetration of the acts contrary to human rights and humanitarian law alleged by the applicant State.”

120 See “Review of the Indictment Pursuant to Rule 61 of the Rules of Procedure and Evidence”, The Prosecutor v. Ivica Rajić, Case No.: IT-95-12-R61, Trial Chamber U, 13 September 1996, para. 25.

121 Cross-Appellant's Brief, paras. 2.14-2.17

122 Cross-Appellant's Brief, paras. 2.16-2.17; Cross-Appellant's Brief in Reply, para. 2.19.

123 Cross-Appellant's Brief, para. 2.56.

124 According to the Prosecution (Cross-Appellant's Brief, para. 2.58), the Court applied the “agency” test when considering whether the contras engaged the responsibility of the United States. The Prosecution has pointed out that in this regard the Court “did not refer to the need for effective control, but rather” — to quote the words of the Court cited by the Prosecution — “whether or not the relationship [… ] was so much one of dependency on the one side and control on the other that it would be right to equate the contras, for legal purposes, with an organ of the United States Government, or as acting on behalf of that Government” (Nicaragua, para. 109).

125 Cross-Appellant's Brief, paras. 2.57-2.58.

126 See Nicaragua, pp. 187-190.

127 See Nicaragua, para. 75

128 See the Advisory Opinion delivered by the ICJ on 29 April 1999 in Difference Relating to the Immunity from Legal Process of a Special Rapporteur of the Commission on Human Rights, para. 62.

129 Customary international law on the matter is correctly restated in Article 5 of the Draft Articles on State Responsibility adopted in its first reading by the United Nations International Law Commission: “For the purposes of the present articles [of Chapter II: The ‘Act of the State’ under International Law], conduct of any State organ having that status under the internal law of that State shall be considered as an act of the State concerned under international law, provided that organ was acting in that capacity in the case in question” (Report of the International Law Commission on the work of its Forty-Eighth Session (6 May-26 July 1996), U.N. Doc. A/51/10, p. 126).

Article 5, as provisionally adopted by the ILC Drafting Committee in 1998, is even clearer. It provides (International Law Commission, Fiftieth Session, 1998, U.N. Doc. A/CN.4/L.569, p. 2):

“ 1. For the purposes of the present articles, the conduct of any State organ acting in that capacity shall be considered an act of that State under international law, whether the organ exercises legislative, executive, judicial or any other functions, whatever position it holds in the organization of the State, and whatever its character as an organ of the central government or of a territorial unit of the State.

2. For the purposes of paragraph 1, an organ includes any person or body which has that status in accordance with the internal law of the State.” (emphasis added).

130 See Article 7 of the ILC Draft Articles on State Responsibility adopted by the International Law Commission on first reading. It provides:

“1. The conduct of an organ of a territorial governmental entity within a State shall also be considered as an act of that State under international law, provided that organ was acting in that capacity in the case in question.

2. The conduct of, an organ of an entity which is not part of the formal structure of the State or of a territorial governmental entity, but which is empowered by the internal law of that State to exercise elements of the governmental authority, shall also be considered as an act of the State under international law, provided that organ was acting in that capacity in the case in question”.

See the First Report on State Responsibility by the Special Rapporteur J. Crawford (22 July 1998), U.N. Doc. A/CN.4/490/ Add.5, pp. 12-16. See also the text of the same provision as provisionally adopted by the ILC Drafting Committee in 1998 (U.N. Doc. A/CN.4/L.569, p. 2). The text of Article 7, as provisionally adopted by the JJLC Drafting Committee in 1998, provides:

“The conduct of an entity which is not an organ of the State under article 5 but which is empowered by the law of that State to exercise elements of the governmental authority shall be considered an act of the State under international law, provided the entity was acting in that capacity in the case in question”, (ibid.)

131 See Nicaragua, paras.75-80.

132 Ibid., para. 86.

133 Ibid. para. 109 (emphasis added).

134 Separate and Dissenting Opinion of Judge McDonald, para. 25.

135 Cross-Appellant's Brief, para. 2.58.

136 See the Separate Opinion of Judge Ago in Nicaragua, paras. 14-17. Judge Ago correctly stated that it fell to the Court first to establish whether the individuals at issue had the status of national officials or officials of national public entities and then, where necessary, to consider whether, lacking this status, they acted instead as de facto State officials, thereby engaging the responsibility of the State. For the purpose of establishing the international responsibility of a State, he therefore identified two broad classes of individuals: those having the status of officials of the State or of its autonomous bodies, and those lacking such a status. Clearly, for Judge Ago the issue of deciding whether an individual had acted as a de facto State organ arose only with respect to the latter category. Furthermore, Judge Ago characterised the CIA and the so-called UCLAs in a manner different from the Court (see para. 15).

137 Judgement, paras. 584-588.

Article 8 of the Draft provides:

“The conduct of a person or group of persons shall also be considered as an act of the State under international law if: a) it is established that such person or group of persons was in fact acting on behalf of that State; or b) such person or group of persons was in fact exercising elements of the governmental authority in the absence of the official authorities and in circumstances which justified the exercise of those elements of authority” (U.N. Doc A/35/10, para. 34, in Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 1980, vol. II (2)).

See also the First Report on State Responsibility by the Special Rapporteur J. Crawford (U.N. Doc. A/CN. 4/490/Add.5, pp. 16-24).

The text of Article 8 as provisionally adopted by the ILC Drafting Committee in 1998 provides:

“The conduct of a person or group of persons shall be considered an act of the State under international law if the person or group of persons was in fact acting on the instructions of, or under the direction or control of, that State in carrying out the conduct” (A/CN.4/L.569, p. 3).

138 Article 10, as adopted on first reading by the International Law Commission, provides:

“The conduct of an organ of a State, of a territorial governmental entity or of an entity empowered to exercise elements of the governmental authority, such organ having acted in that capacity, shall be considered as an act of the State under international law even if, in the particular case, the organ exceeded its competence according to internal law or contravened instructions concerning its activity”. (Report of the International Law Commission on the work of its thirty-second session (5 Ma.y-25 My 1980), U.N. Doc. A/35/10, p.31).

See also the First Report on State Responsibility by the Special Rapporteur J. Crawford, U.N. Doc. A/CN./490/Add.5, pp. 29-31. The text of article 10, as provisionally adopted in 1998 by the ILC Drafting Committee, provides:

“The conduct of an organ of a State or of an entity empowered to exercise elements of the governmental authority, such organ or entity having acted in that capacity, shall be considered an act of the State under international law even if, in the particular case, the organ or entity exceeded its authority or contravened instructions concerning its exercise” (U.N. Doc. A/CN.4/L.569,p.3).

139 This sort of “objective” State responsibility also arises in a different case. Under the relevant rules on State responsibility as laid down in Article 7 of the International Law Commission Draft, a State incurs responsibility for acts of organs of its territorial governmental entities (regions, Lander, provinces, member States of Federal States, etc.) even if under the national Constitution these organs enjoy broad independence or complete autonomy. (See footnote 130 above)

140 The United States claimed that Mexico was responsible for the killing of United States nationals at the hands of a mob with the participation of Mexican soldiers. Mexico objected that, even if it were assumed that the soldiers were guilty of such participation, Mexico should not be held responsible for the wrongful acts of the soldiers, on the grounds that they had been ordered by the highest official in the locality to protect American citizens. Instead of carrying out these orders, however, they had acted in violation of them, in consequence of which the Americans had been killed. The Mexico/United States General Claims Commission dismissed the Mexican objection and held Mexico responsible. It stated that if international law were not to impute to a State wrongful acts committed by its officials outside their competence or contrary to instructions, “it would follow that no wrongful acts committed by an official could be considered as acts for which his Government could be held liable”. It then added that:

“[s]oldiers inflicting personal injuries or committing wanton destruction or looting always act in disobedience of some rules laid down by superior authority. There could be no [international State] liability whatever for such misdeeds if the view were taken that any acts committed by soldiers in contravention of instructions must always be considered as personal acts” (Thomas H. Youmans (U.S.A.)v.United Mexican States, Decision of 23 November 1926, Reports of International Arbitral Awads vol. IV, p. 116).

141 See United States v. Mexico (Stephens Case), Reports of International Arbitral Awards, vol. IV, pp. 266-267.

142 See Kenneth P. Yeager v. Islamic Republic of Iran, 17 Iran-U.S. Claims Tribunal Reports, 1987, vol. IV, p. 92).

143 Ibid., para. 23.

144 Ibid., para. 37.

145 Ibid., paras 39,45. The Claims Tribunal went on to note that:

“ [w]hile there were complaints about a lack of discipline among the numerous Komitehs, Ayatollah Khomeini stood behind them, and the Komitehs, in general, were loyal to him and the clergy. Soon after the victory of the Revolution, the Komitehs, contrary to other groups, obtained a firm position within the State structure and were eventually conferred a permanent place in the State budget” (ibid., para. 39; emphasis added).

146 Ibid., paras. 12,41.

147 Ibid., para. 61.

148 United States Diplomatic and Consular Staff in Tehran, Judgment, ICJ Reports (1980), p. 13, para. 17.

149 The Claims Tribunal stated the following:

“The Tribunal finds sufficient evidence in the record to establish a presumption that revolutionary ‘Komitehs’ or ‘Guards’ after 11 February 1979 were acting in fact on behalf of the new government, or at least exercised elements of governmental authority in the absence of official authorities, in operations of which the new Government must have had knowledge and to which it did not specifically object. Under those circumstances, and for the kind of measures involved here, the Respondent has the burden of coming forward with evidence showing that members of ‘Komitehs’ or ‘Guards’ were in fact not acting on its behalf, or were not exercising elements of government authority, or that it could not control them”. (Kenneth P. Yeager v. Islamic Republic of Iran, YJ Iran-U.S. Claims Tribunal Reports, 1987, vol. IV. p. 92, at para. 43).

150 The Claims Tribunal went on to say:

“[…] Rather, the evidence suggests that the new government, despite occasional complaints about a lack of discipline, stood behind them [the Komitehs]. The Tribunal is persuaded, therefore, that the revolutionary ‘Komitehs’ or ‘Guards’ involved in this Case, were acting'for'Iran.” (para. 44).

The Tribunal then concluded that:

“[n]or has the Respondent established that it could not control the revolutionary ‘Komitehs’ or ‘Guards’ in this operation [namely, forcing foreigners to leave the country]. Because the new government accepted their activity in principle and their role in the maintenance of public security, calls for more discipline, phrased in general rather than specific terms, do not meet the standard of control required in order to effectively prevent these groups from committing wrongful acts against United States nationals. Under international law Iran cannot, on the one hand, tolerate the exercise of governmental authority by revolutionary ‘Komitehs’ or ‘Guards’ and at the same time deny responsibility for wrongful acts committed by them” (para. 45).

151 See William L. Pereira Associates, Iran v. Islamic Republic of Iran, Award No. 116-1-3, 5 Iran-U.S. Claims Tribunal 1984, p. 198 at p. 226. See also Arthur Young and Company v. Islamic Republic of Iran, Telecommunications Company of Iran, Social Security Organization of Iran, Award No. 338-484-1,17 Iran-U.S. Claims Tribunal Reports, 1987, p. 245). Here the Claims Tribunal found that in the circumstances of the case Iran was not responsible because there was no causal link between the action of the revolutionary guards and the alleged breach of international law. However, the Claims Tribunal held that otherwise Iran might have incurred international responsibility for acts of “armed men wearing patches on their pockets identifying them as members of the revolutionary guards” (para. 53). A similar stand was taken in Schott v. Islamic Republic of Iran, Award No. 474-268-1, 24 Iran-U.S. Claims Tribunal Reports, 1990, p. 203 at para. 59.

In Daley, on the other hand, the Claims Tribunal held Iran responsible for the expropriation of a car, for the five Iranian “Revolutionary Guards” who had taken the car were “in army-type uniforms” at the entrance of a hotel which had come “under the control of Revolutionary Guards” a few days before. (Daley v. Islamic Republic of Iran, Award No. 360-1-514-1,18 Iran-U.S Claims Tribunal Reports, 1988,232 at paras. 19-20).

152 Loizidou v. Turkey (Merits), Eur. Court of H. R. Judgement of 18 December 1996 (40/1993/435/514).

153 In its judgement, the Court stated the following on the point at issue here:

“It is not necessary to determine whether, as the applicant and the Government of Cyprus have suggested, Turkey actually exercises detailed control over the policies and actions of the authorities of the “TRNC”. It is obvious from the large number of troops engaged in active duties in northern Cyprus [… ] that her army exercises effective overall control over that part of the island. Such control, according to the relevant test and in the circumstances of the case, entails her responsibility for the policies and actions of the ‘TRNC […]” (ibid., para. 56).

154 2 St E 8/96 (unpublished typescript; kindly provided by the German Embassy to the Netherlands and on file with the International Tribunal's Library).

155 The Court stated the following:

“The conflict in Bosnia-Herzegovina was an international conflict for the purposes of Article 2 of the Fourth Geneva Convention. Owing to the declaration of independence and the referendum of 29 February and 1 March 1992 and to international recognition on 6 April -1992, Bosnia-Herzegovina had become an autonomous State, independent from Yugoslavia.

The aimed conflict that took place on its territory in the following period was not an internal clash (conflict) in which an ethnic group was trying to break with the existing State of Bosnia-Herzegovina and which [as a consequence] had no international character. The expert witness Fischer pointed out that, by using the term international humanitarian law applicable to this conflict, the United Nations Security Council has used the term usual in international terminology to refer to the law applicable to international armed conflicts. This [according to the expert witness] showed that the Security-Council considered the conflict to be international. The expert witness Fischer cited the following circumstances as indicia of an international conflict according to the prevailing view in international law: the participation of organs of a State in a conflict on the territory of another State, e.g. the participation of officers in the clashes, or the financing of and provision of technical equipment to one party to the conflict by another State; the latter at least when it is combined with the aforementioned interconnection [Verflechtung] between personnel. According to this Chamber's findings, these criteria are met in the case at hand. The Chamber has found that at the beginning of May officers of the JNA, which at that time was purely Serb, began taking Doboj and the surrounding villages. There can, therefore, be no doubt regarding the existence of an international armed conflict at that point in time. However, this Chamber has further found that after 19 May 1992, when the JNA officially withdrew from Bosnia-Herzegovina, officers of the JNA continued to be employed in Bosnia-Herzegovina and paid by Belgrade, and that at the end of May materiel, weapons and vehicles were still being brought from Belgrade to Bosnia-Herzegovina. As a consequence, a close personal, Organizational and logistical interconnection [Verflechtung] of the Bosnian-Serb army, paramilitary groups and the JNA persisted. The headquarters of the Bosnian-Serb army, maintained a liaison office in Belgrade.” (ibid pp. 158-160 of the unpublished typescript; unofficial translation).

156 The Judgement of the Düsseldorf Court of Appeal was upheld on appeal by the Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof) by a judgement of 30 April 1999 (unpublished). The appeal was based, inter alia, on a misapplication of substantive law. This ground also included the question of whether the conflict was international in character. The Bundesgerichtshof did not address the matter specifically, thus implicitly upholding the judgement of the Düsseldorf Court. (See, in particular, pp. 19-20 and 23 of the German typescript (3 S t R 215/98), on file with the International Tribunal library)

157 See e.g., the debates in the U.N. Security Council in 1976, on the raids of South Africa into Zambia to destroy bases of the SWAPO (see in particular the statements of Zambia (SCOR, 1944th Meeting of 27 July 1976, paras. 10-45) and South Africa (ibid., paras. 47-69); see also SC resolution no. 393 (1976) of 30 July 1976)); see also the debates on the Israeli raids in Lebanon in June 1982’ (in particular the statements of Ireland (SCOR, 2374th Meeting of 5 June 1982, paras. 35-36) and of Israel (ibid., paras. 74-78 and SCOR, 2375th Meeting of 6 June 1982, paras. 22-67) and in July-August 1982 (see the statement of Israel, SCOR, 2385th Meeting of 29 July 1982, paras. 144-169)); see also the debates on the South African raid in Lesotho in December 1982 (see in particular the statements of France (SCOR, 2407th Meeting of 15 December 1982, paras. 69-80), of Japan (ibid., paras. 98-107), of South Africa (SCOR, 2409th Meeting of 16 December 1982, paras. 126-160) and of Lesotho (ibid., paras. 219-227)).

Although there does not seem to exist any international practice in this area, it may happen that a State simply providing economic and military assistance to a military group (hence not necessarily exercising effective control over the group) directs a member of the group or the whole group to perform a specific internationally wrongful act, e.g. an international crime such as genocide. In, this case one would face a situation similar to that described above, in the text, of a State issuing specific instructions to an individual.

158 See Nicaragua, paras. 239-249,292(3) and 292(4).

159 United States Diplomatic and Consular Staff in Tehran, Judgment, ICJ Reports (1980), pp. 3 ff.

160 The Court stated the following:

“No suggestion has been made that the militants; when they executed their attack on the Embassy, had any form of official status as recognised ‘agents’ or organs of the Iranian State. Their conduct in mounting the attack, overrunning the Embassy and seizing its inmates as hostages cannot, therefore, be regarded as imputable to that State on that basis. Their conduct might be considered as itself directly imputable to the Iranian State only if it were established that, in fact, on the occasion in question the militants acted on behalf of the State, having been charged by some competent organ of the Iranian State to carry out a specific operation. The information before the Court does not, however, suffice to establish with the requisite certainty the existence at that time of such a link between the militants and any competent organ of the State“ (ibid., p. 30, para. 58; emphasis added).

161 Ibid pp. 30-33 (paras. 60-68).

162 The Court stated the following:

“The policy thus announced by the Ayatollah Khomeini, of maintaining the occupation of the Embassy and the detention of its inmates as hostages for the purpose of exerting pressure on the United States Government was complied with by other Iranian authorities and endorsed by them repeatedly in statements made in various contexts. The result of that policy was fundamentally to transform the legal nature of the situation created by the occupation of the Embassy and the detention of its diplomatic and consular staff as hostages. The approval given to these facts by the Ayatollah Khomeini and other organs of the Iranian State, and the decision to perpetuate them, translated continuing occupation of the Embassy and detention of the hostages into acts of that State. The militants, authors of the invasion and jailers of the hostages, had now become agents of the Iranian State for whose acts the State itself was internationally responsible […].” (ibid., p. 35, para. 74; emphasis added).

163 See Nicaragua, para. 75.,

164 Ibid., para. 80.

165 Alfred W. Short v. Islamic Republic of Iran, Award No. 312-1.1135-3,16 Iran-U.S. Claims Tribunal Reports 1987, p. 76).

166 After finding that the acts of the revolutionaries could not be attributed to Iran, the Claims Tribunal noted the following:

“The Claimant's reliance on the declarations made by the leader of the Revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini, and other spokesmen of the revolutionary movement, also lack the essential ingredient as being the cause for the Claimant's departure in circumstances amounting to an expulsion. While these statements are of anti-foreign and in particular anti-American sentiment, the Tribunal notes that these pronouncements were of a general nature and did not specify that Americans should be expelled en masse.” (ibid., para. 35).

167 For examples of State practice apparently adopting this approach to the question of attribution, see for instance the relevant documents in the Cesare Rossi case (an Italian antifascist staying in Switzerland who was lured by two other Italians acting on behalf of the Italian authorities into crossing the border with Italy, where he was arrested: see 1 Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht, 1929, pp. 280-294); the Jacob Salomon case (a German national was kidnapped by another German national in Switzerland and taken to Germany: see the relevant documents mentioned in 29 American Journal of International Law 1935, pp. 502-507, 36 American Journal of International Law 1936, pp.123-124). See further the Sabotage cases decided by the United States-Germany Mixed Claims Commission (Lehigh Valley Railroad Co., Agency of Canadian Can and Foundry Co., Ltd., and various underwriters (United States) v. Germany, Reports of International Arbitral Awards, vol. VIII, pp. $Aff. (especially pp. 84-87) and pp. 225 ff. (especially 457-460). In these cases, in July 1916 some individuals, at the request of the German authorities intent on bringing about sabotage in the United States, had set fire to a terminal in New York harbour and to a plant of a company in New Jersey.

Mention can also be made of the Eichmann case (Attorney-General of the Government of Israel v. Adolf Eichmann, 36 International Law Reports 1968, pp. 277-344): see for instance Security Council resolution 4349 of 23 June 1960 and the debates in the Security Council; see in particular the statements of Argentina (SCOR, 865th Meeting of 22 June 1960, paras. 25-27), of Israel (SCOR of the 866th Meeting on 22 June 1960, para. 41), of Italy (SCOR of the 867th Meeting of 23 June 1960, paras. 32-34), of Ecuador (ibid., paras. 47-49), of Tunisia (ibid., para. 73) and of Ceylon (SCOR of the 868th Meeting of 23 June 1960, paras. 12-13).

In many of these cases, the need for specific instructions by the State concerning the commission of the specific act with which the individual had been charged, or the ex post facto public endorsement of that act, can be inferred from the facts of the case.

168 These cases, although they concern war crimes (the notion of “grave breaches” had not yet come into existence at the time), are nevertheless relevant to our discussion. Indeed, they provide useful indications concerning the conditions on which civilians may be assimilated to State officials.

169 Trial of Joseph Kramer and 44 Others, British Military Court, Luneberg, 17th September-17th November, 1945, Law Reports of Trials of War Criminals, Selected and Prepared by the United Nations War Crimes Commission, Published for the United Nations War Crimes Commission by His Majesty's Stationary Office, London 1947 (“UNWCC“), vol. U, p. 1.

170 Ibid., p. 152 (emphasis added) (the Austrian civilian, Schlomowicz, was not found guilty). See also ibid., p. 109. Most of the accused civilians were found guilty and sentenced to imprisonment. It is clear from this case that according to the court, by acting as de facto members of the German apparatus running the Belsen concentration camp, the Polish civilians could be assimilated to German State officials.

171 Public Prosecutor v. Menten,15 International Law Reports 1987, pp. 33

172 The court stated the following:

“Since Menten, on the orders of the Befehlshaber of the Sicherheitspolizei in Poland, was dressed in the uniform of an under-officer of this branch of the [German] police when he was dem Einsatzkommando als Dolmetscher zugeteilt [assigned to the Special forces as interpreter], the [District] Court [of Amsterdam in its judgement of 14 December 1977] was justified in assuming that his position in the Einsatzkommando and his performance in within it of a more or less official character. Thus the relationship to the enemy in which Menten rendered incidental services was of such a nature that he could be regarded as a functionary of the enemy.” (ibid., p. 347. The English translation has been slightly corrected by the Appeals Chamber to bring it into line with the Dutch original, which can be found in Nederlandse Jurisprudence, 1978, no. 358, p. 1236).

The court concluded that:

“from the above-mentioned evidence, taken together with the other evidence that in July 1941 Menten, dressed in a German uniform and in company with a number of other persons also so dressed, came to Podhorodce [… ] and was present at the killings, [it can be inferred] that he was there with members of the German Staff and that he rendered services to this Staff at the time of and in connection with these killings.” (ibid., p. 348).

173 Menten was sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment by the District Court of Rotterdam (Judgement of 9 July 1980, ibid., p. 361). It should be pointed out that the Dutch Court of Cassation had been obliged to investigate whether Menten was “in military, state or public service of or with the enemy” as this was an ingredient of the relevant Dutch law (ibid., p. 346). The Appeals Chamber holds, however, that the Menten case is in line with the rules of general international law concerning the assimilation of private individuals to State officials.

174 See, e.g., the Daley case, where the Iran U.S. Claims Tribunal attributed international responsibility to Iran for acts of five Iranian “Revolutionary Guards” in “army type uniforms” (18 Iran-V.S. Claims Tribunal Reports, 1988, p. 238, at para. 19).

175 In this connection mention can be made of the Stocké case brought before the European Commission of Human Rights. A German national fled from Germany to Switzerland and then to France to avoid arrest in Germany for alleged tax offences. He was then tricked into re-entering Germany by a police informant and was arrested. He then claimed before the European Commission of Human Rights that he had been arrested in violation of Article 5(1) of the ECHR. The Commission held that:

“[i]n the case of collusion between State authorities, i.e. any State official irrespective of his hierarchical position, and a private individual for the purpose of returning against his will a person living abroad, without consent of his State of residence, to the territory where he is prosecuted, the High Contracting Party concerned incurs responsibility for the acts of the private individual who de facto acts on its behalf. The Commission considers that such circumstances may render this person's arrest and detention unlawful within the meaning of article 5(1) of the Convention” (Stocké v. Federal Republic of Germany, Eur. Court H. R. judgement of 19 March 1991, Series A, no 199, para. 168 (Opinion of the Commission).

Although these cases concerned State responsibility, they may be relevant to the question of the criminal responsibility of individuals perpetrating grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions, inasmuch as they set out the conditions necessary for individuals to be considered as de facto State organs.

176 See Separate and Dissenting Opinion of Judge McDonald, para. 1: “I completely agree with and share in the Opinion and Judgment with the exception of the determination that Article 2 of the Statute is inapplicable to the .charges against the accused.“

177 Judgement, para. 601.

178 Ibid.

179 Ibid., paras. 601-602

180 As Judge McDonald noted:

“[t]he creation of the VRS [after 19 May 1992] was a legal fiction. The only changes made after the 15 May 1992 Security Council resolution were the transfer of troops, the establishment of a Main Staff of the VRS, a change in the name of the military Organization and individual units, and a change in the insignia. There remained the same weapons, the same equipment, the same officers, the same commanders, largely the.same troops, the same logistics centres, the same suppliers, the same infrastructure, the same source of payments, the same goals and mission, the same tactics, and the same operations. Importantly, the objective remained the same [… ] The,VRS clearly continued to operate as an integrated and instrumental part of the Serbian war effort. [… ] The VRS Main Staff, the members of which had all been generals in the JNA and many of whom were appointed to their positions by the JNA General Staff, maintained direct communications with the VJ General Staff via a communications link from Belgrade. [… ] Moreover, the VRS continued i to receive supplies from the same suppliers in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) who had contracted with the JNA, although the requests after 19 May 1992 went through the Chief of Staff of the VRS who then sent them onto Belgrade.” (Separate and Dissenting Opinion of Judge McDonald, paras 7-8).

181 In the light of the demand of the Security Council on 15 May 1992 that all interference from outside Bosnia and Herzegovina by units of the JNA cease immediately, the Trial Chamber characterised the dilemma posed for the JNA by increasing international scrutiny from 1991 onwards in terms of the way in which the JNA could:

“be converted into an army of what remained of Yugoslavia, namely Serbia and Montenegro, yet continue to retain in Serb hands control of substantial portions of Bosnia and Herzegovina while appearing to comply with international demands that the JNA quit Bosnia and Herzegovina. [… ] The solution as far as Serbia was concerned was found by transferring to Bosnia and Herzegovina all Bosnian Serb soldiers serving in JNA units elsewhere while sending all non-Bosnian soldiers out of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This ensured seeming compliance with international demands while effectively retaining large ethnic Serb armed forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina” (Judgement, paras. 113-114).

Additionally, the U.N. Secretary-General, in commenting on its purported withdrawal from Bosnia and Herzegovina, concluded in his report of 3 December 1992 that “[t]hough JNA has withdrawn completely from Bosnia and Herzegovina, former members of Bosnian Serb origin have been left behind with their equipment and constitute the Army of the ‘Serb Republic'” (Report of the Secretary-General concerning the situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina, U.N. Doc. A/47/747, para. 10).

182 Judgement, para. 115:

“[T]he VRS was in effect a product of the dissolution of the old JNA and the withdrawal of its non-Bosnian elements into Serbia. However, most, if not all, of the commanding officers of units of the old JNA who found themselves stationed with their units in Bosnia and Herzegovina on 18 May 1992, nearly all Serbs, remained in command of those units throughout 1992and 1993 […]”.

See further ibid., para. 590: “The attack on Kozarac was carried out by elements of an army Corps based in Banja Luka. This Corps, previously a Corps of the old JNA, became part of the VRS and was renamed the ‘Banja Luka’ or ‘1st Krajina’ Corps after 19 May 1992 but retained the same commander.” See also ibid., paras. 114-116,118-121,594.

183 Ibid., para. ils (“Despite the announced JNA withdrawal from Bosnia and Herzegovina in May 1992, active elements of what had been the JNA, now rechristened as the VJ [… ] remained in Bosnia and Herzegovina after the May withdrawal and worked with the VRS throughout 1992 and 1993“) and para. 569 (“[…] the forces of the VJ continued to be involved in the armed conflict after that date“).

184 See in particular ibid., para. 566:

“The ongoing conflicts before, during and after the time of the attack on Kozarac on 24 May 1992 were taking place and continued to take place throughout the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina between the government of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the Bosnian Serb forces, elements of the VJ operating from time to time in the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and various paramilitary groups, all of which occupied or were proceeding to occupy a significant portion of the territory of that State.”

See also para. 579: “[T]he take-over of opština Prijedor began before the JNA withdrawal on 19 May 1992 and was not completed until after that date”. See also the Dissenting Opinion of Judge McDonald who noted “[t]he continuity between the JNA and the VRS particularly as it relates to the military operations in the Opština Prijedor area […].” (Separate and Dissenting Opinion of Judge McDonald, para. 15).

185 Moreover, it is interesting to observe that while concluding that by 19 May 1992 effective control over the VRS had been lost by the JNA/VJ, the Trial Chamber simultaneously observed that such control nevertheless did not appear to have been regained by the Bosnian authorities. In particular, the Trial Chamber found that the “Government of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina [… ] faced […] major problems [… ] of defence, involving control over the mobilization and operations of the armed forces” (Judgement, para. 124, emphasis added).

186 In and of itself, the logistical difficulties of disengaging from the conflict and withdrawing such a large force would have been considerable. With regard to the extent and depth of the involvement of the large number of JNA forces engaged in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the ongoing nature of their activities beyond 19 May 1992, see ibid., paras. 124-125: “By early 1992 there were some 100,000 JNA troops in Bosnia and Herzegovina with over 700 tanks, 1,000 armoured personnel carriers, much heavy weaponry, 100 planes and 500 helicopters, all under the command of the General Staff of the JNA in Belgrade. [… ] On 19 May 1992 the withdrawal of JNA forces from Bosnia and Herzegovina was announced but the attacks were continued by the VRS.”

187 See in particular ibid., para. 116 (citing the 1993 publication of the former Yugoslav Federal Secretary for Defence, General Veljko Kadijevic, entitled My view of the Break-up: an Army without a State (Prosecution Exhibit 30)):

“[T]he units and headquarters of the JNA formed the backbone of the army of the Serb Republic (Republic of Srpska) complete with weaponry and equipment [… ] [Fjirst the JNA and later the army of the Republic of Srpska, which the JNA put on its feet, helped to liberate Serb territory, protect the Serb nation and create the favourable military preconditions for achieving the interests and rights of the Serb nation in Bosnia and Herzegovina…”.

See also para. 590:

“The occupation of Kozarac and of the surrounding villages was part of a military and political operation, begun before 19 May 1992 with the take-over of the town of Prijedor of 29 April 1992, aimed at establishing control over the opstina which formed part of the land corridor of Bosnian territory linking the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) with the so-called Republic of Serbian Krajina in Croatia.”

188 While the relationship between the JNA and VRS may have included coordination and cooperation, it cannot be seen as limited to this. As the Trial Chamber itself noted: “In 1991 and on into 1992 the Bosnian Serb and Croatian Serb paramilitary forces cooperated with and acted under the command and within the framework of the JNA.1‘(ibid., para. 593; emphasis added).

189 Ibid., para. 598:

“The Trial Chamber has already considered the overwhelming importance of the logistical support provided by the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) to the VRS. [….] [JJn addition to routing all high-level VRS communications through secure links in Belgrade, a communications link for everyday use was established and maintained between VRS Main Staff Headquarters and the VJ Main Staff in Belgrade […].”

190 Ibid., para. 601

191 The Trial Chamber noted that:

“[i]t is clear from the evidence that the military and political objectives of the Republika Srpska and of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) were largely complementary. [… ] The [… ] political leadership of the Republika Srpska and their senior military commanders no doubt considered the success of the overall Serbian war effort as a prerequisite to their stated political aim of joining with Serbia and Montenegro as part of a Greater Serbia. [… ] In that sense, there was little need for the VJ and the Government of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) to attempt to exercise any real degree of control over, as distinct from coordination with, the VRS. So long as the Republika Srpska and the VRS remained committed to the shared strategic objectives of the war, and the Main Staffs of the two armies could coordinate their activities at the highest levels, it was sufficient for the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) and the VJ to provide the VRS .with logistical supplies and, where necessary, to supplement the Bosnian elements of the VRS officer corps with non-Bosnian VJ or former JNA officers, to ensure that this process was continued” (ibid., paras. 603-604).

192 Ibid, para. 602. On this point, the Trial Chamber noted, further, that:

“given that the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) had taken responsibility for the financing of the VRS, most of which consisted of former JNA soldiers and officers, it is a fact not to be wondered at that such financing would not only include payments to soldiers and officers but that existing administrative mechanisms for financing those soldiers and their operations would be relied on after 19 May 1992[…].” ibid.:

193 Ibid.

194 See in this regard the testimony of the expert witness Dr. James Gow, transcript of hearing in The Prosecutor v. Duško Tadić, Case No.: IT-94-1-T, 10 May 1996, pp. 308-309; ibid., 13 May 1996, pp. 330-338.

195 Judgement, para. 605.

196 It was deemed insufficient by the Trial Chamber that the VJ” ‘made use of the potential for control inherent in that dependence', or was otherwise given effective control over those forces […]” (ibid.; emphasis added).

197 The Trial Chamber noted that:

“the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro), through the dependence of the VRS on the supply of materiel by the VJ, had the capability to exercise great influence and perhaps even control over the VRS [… ] [However] there is no evidence on which this Trial Chamber can conclude that the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) and the VJ ever directed or, for that matter, ever felt the need to attempt to direct, the actual military operations of the VRS […]” (ibid.).

198 See Report of the Co-Chairmen of the Steering Committee of the International Conference on the Former Yugoslavia on the establishment and commencement of operations of an International Conference on the Former Yugoslavia Mission to the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro), S/1994/1074,19 September 1996, p. 3, where it is noted that as of 4 August 1994, the Government of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) ordered, inter alia, the breaking off of political and economic relations with the Republika Srpska and the closure of the border between the Republika Srpska and the FRY to all transport towards the Republika Srpska, except food, clothing and medicine. International observers were deployed to monitor compliance with these measures, and it was reported by the Co-Chairmen that the Government of the FRY appeared to be “meeting its commitment to close the border between the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) and the areas of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina under the control of the Bosnian Serb forces.“ (Report of the Co-Chairmen of the Steering Committee of the International Conference on the^ Former Yugoslavia on the state of implementation of the border closure measures taken by the authorities of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro), S/1994/1124,3 October 1994, pp. 2-3).

199 As outlined below, this process culminated in the agreement of the Republika Srpska to be represented at the Dayton conference by the FRY (below, at paragraph 159). This appears to have been in spite of intense opposition, within the Republika Srpska, to the peace settlements proposed by the international community, as is evidenced by the overwhelming rejection by the Bosnian Serbs of the international community's peace plan for Bosnia and Herzegovina in a referendum which took place in Bosnian Serb-held territory on 27-28 August 1994 (See Report of the Secretary-General on the Work of the Organization, UNGAOR, 49th sess., supp. no. 1 (A/49/1), 2 September 1994, p. 95).

200 This agreement stipulated that the delegation of the Republika Srpska was to be “headed by the President of the Republic of Serbia Mr. Slobodan Milosevic” (Article 2). Pursuant to this agreement, the leadership of the Republika Srpska agreed “to adopt the binding decisions of the delegation, regarding the Peace Plan, in plenary sessions, by simple majority. In the case of divided votes, the vote of the President, Mr. Slobodan Milosevic, shall be decisive” (Article 3). That Mr. Milosevic was head of the joint delegation was confirmed by Mr. Milosevic himself in his letter of 21 November 1995 to President Izetbegovic concerning Annex 9 to the Dayton-Paris Accord. (Agreement on file with the International Tribunal's Library).

201 This letter had been signed by Mr. Milutinović, Foreign Minister of the FRY, following a request of 20 November 1995 of the three members of the “Delegation of Republika Srpska” to Mr. Milošević.

202 See the texts of the Dayton-Paris Accord (General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina, initialled by the parties on 21 November 1995, U.N. Doc. A/50/790, S/1995/999,30 November 1995).

203 Article 4(2) of Geneva Convention IV provides as follows:

“Nationals of a State which is not bound by the Convention are not protected by it. Nationals of a neutral State who find themselves in the territory of a belligerent State, and nationals of a co-belligerent State, shall not be regarded as protected persons while the State of which they are nationals has normal diplomatic representation in the State in whose hands they are”.

204 The preparatory works of the Convention suggests an intent on the part of the drafters to extend its application, inter alia, to persons having the nationality of a Party to the conflict who have been expelled by that Party or who have fled abroad, acquiring the status of refugees. If these persons subsequently happen to find themselves on the territory of the other Party to the conflict occupied by their national State, they nevertheless do not lose the status of “protected persons” (see Final Record of the Diplomatic Conference of Geneva of 1949, vol. II, pp. 561-562,793-796, 813-814).

205 See also Article 44 of Geneva Convention IV:

“In applying the measures of control mentioned in the present Convention, the Detaining Power shall not treat as enemy aliens exclusively on the basis of their nationality de jure of an enemy State, refugees who do not, in fact, enjoy the protection of any government.”

In addition, see Article 70(2):

“Nationals of the Occupying Power who, before the outbreak of hostilities, have sought refuge in the territory of the occupied State, shall not be arrested, prosecuted, convicted or deported from the occupied territory, except for the offences committed after the outbreak of hostilities, or for offences under common law committed before the outbreak of hostilities which, according to the law of the occupied State, would have justified extradition in time of peace.”

206 Cross-Appellant's Brief, para. 3.6.

207 T. 169 (20 April 1999).

208 T. 170 (20 April 1999).

209 T. 176 (20 April 1999).

210 Cross-Appellant's Brief, para. 3.12.

211 Judgement, para. 373.

212 Skeleton Argument of the Prosecution, para. 42.

213 Judgement, para. 373: “The bare possibility that the deaths of the Jaskići villagers were the result of encountering a part of that large force would be enough [… ] to prevent satisfaction beyond reasonable doubt that the accused was involved in those deaths.“

214 Ibid., para. 373: “The fact that there was no killing at Sivci could suggest that the killing of villagers was not a planned part of this particular episode of ethnic cleansing of the two villages, in which the accused took part […].”

215 T. 172 (20 April 1999).

216 Cross-Appellant's Brief, para.3.19

217 Ibid., paras. 3.24,3.27.

218 Cross-Appellant's Brief, paras. 3.27-3.29; T.; 179-180 (20 April1999). ‘

219 Cross-Appellant's Brief, para. 3.29.

220 Defence's Substituted Response to Cross-Appellant's Brief, paras. 3.8-3.10; Defence!s Skeleton Argument on the Cross-Appeal, para.

221 T. 251 (21 April 1999).

222 Defence's Substituted Response to Cross-Appellant's Brief, para. 3.19; Defence's Skeleton Argument on the Cross-Appeal, para. 2(d).

223 Defence's Substituted Response to Cross-Appellant's Brief, paras. 3.9-3.10; Defence's Skeleton Argument on the Cross-Appeal, para. 2(d).

224 Judgement,paras.369,373.

225 Ibid., paras. 370-373.

226 Ibid., para. 373

227 Ibid.

228 An example is provided by Article 27 para. 1 of the Italian Constitution (“La responsibilità penale èpersonale.” (“Criminal responsibility is personal.“) (unofficial translation)).

229 See for instance Article 121-1 of the French Code penal (“Nul n'est responsable, pénalement que de son propre fait“), para. 4 of the Austrian Strafgesetzbuch (“Strafbar ist nur, wer schuldhaft handelt” (“Only he who is culpable may be punished“) (unofficial translation)).

230 This rather basic proposition is usually tacitly assumed rather than explicitly acknowledged. For. an example of where it was expressly stated, however, see, for Great Britain, R. v. Dalloway (1847) 3 Cox CC 273. See also the various decisions of the German Constitutional Court, e.g., BverfGE 6,389 (439) and 50,125 (133), as well as decisions of the German Federal Court of Justice (e.g., BGHSt 2,194 (200)).

231 Report of the Secretary-General Pursuant to Paragraph 2 of Security Council Resolution 808 (1993), U.N. Doc. S/25704,3 May 1993 (“Report of the Secretary-General“), para. 53 (emphasis added).

232 Ibid., para 54 (emphasis added).

233 Trial of Otto Sandrock and three others, British Military Court for the Trial of War Criminals, held at the Court House, Almelo, Holland, on24-26November, 1945,UNWCC, vol. 1,p. 35).

234 The accused were German non-commissioned officers who had executed a British prisoner of war and a Dutch civilian in the house of whom the British airman was hiding. On the occasion of each execution one of the Germans had fired the-lethal shot, another had given the order and a third had remained by the car used to go to a wood on the outskirts of the Dutch town of Almelo, to prevent people from coming near while the shooting took place. The Prosecutor stated that “the analogy which seemed to him most fitting in this case was that of a gangster crime, every member of the gang being equally responsible with the man who fired the actual shot” (ibid., p. 37). In his summing up the Judge Advocate pointed out that:

“There is no dispute, as I understand it, that all three [Germans] knew what they were doing and had gone there for the very purpose of having this officer killed; and, as you know, if people are all present together at the same time taking part in a common enterprise which is unlawful, each one in their (sic) own way assisting the common purpose of all, they are all equally guilty in point of law” (see official transcript, Public Record Office, London, WO 235/8, p. 70; copy on file with the International Tribunal's Library; the report in the UNWCC, vol. I, p. 40 is slightly different).

All the accused were found guilty, but those who had ordered the shooting or carried out the shooting were sentenced to death, whereas the others were sentenced to fifteen years imprisonment (ibid., p. 41).

235 Hoelzer et al, Canadian Military Court, Aurich, Germany, Record of Proceedings 25 March-6 April 1946, vol. I, pp. 341, 347, 349 (RCAF Binder 181.009 (D2474); copy on file with the International Tribunal's Library).

236 Trial of Gustav Alfred Jepsen and others, Proceedings of a War Crimes Trial held at Luneberg, Germany (13-23 August, 1946), judgement of 24 August 1946 (original transcripts in Public Record Office, Kew, Richmond; on file with the International Tribunal's Library).

237 Ibid., p. 241

238 Trial of Franz Schonfeld and others, British Military Court, Essen, June 1 lth-26th, 1946, UNWCC, vol. XI, p. 68 (summing up of the Judge Advocate).

239 Trial of Feurstein and others, Proceedings of a War Crimes Trial held at Hamburg, Germany (4-24 August, 1948), judgement of 24 August 1948 (original transcripts in Public Record Office, Kew, Richmond; on file with the International Tribunal's Library).

240 The Prosecutor had stated the following:

“It is an opening principle of English law, and indeed of all law, that a man is responsible for his acts and is taken to intend the natural and normal consequences of his acts and if these men [… ]set the machinery in motion by which the four men were shot, then they are guilty of the crime of killing these men. It does not—it never has been essential for any one of these men to have taken those soldiers out themselves and to have personally executed them or personally dispatched them. That is not at all necessary; all that is necessary to make them responsible is that they set the machinery in motion which ended in the volleys that killed the four men we are concerned with” (ibid., p. 4).

241 Ibid., summing up of the Judge Advocate, p. 7.

242 In this regard, the Judge Advocate noted that: “[o]f course, it is quite possible that it [the criminal offence] might have taken place in the absence of all these accused here, but that does not mean the same thing as saying [… ] that[the accused] could not be a chain in the link of causation […]” (ibid., pp. 7-8).