No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

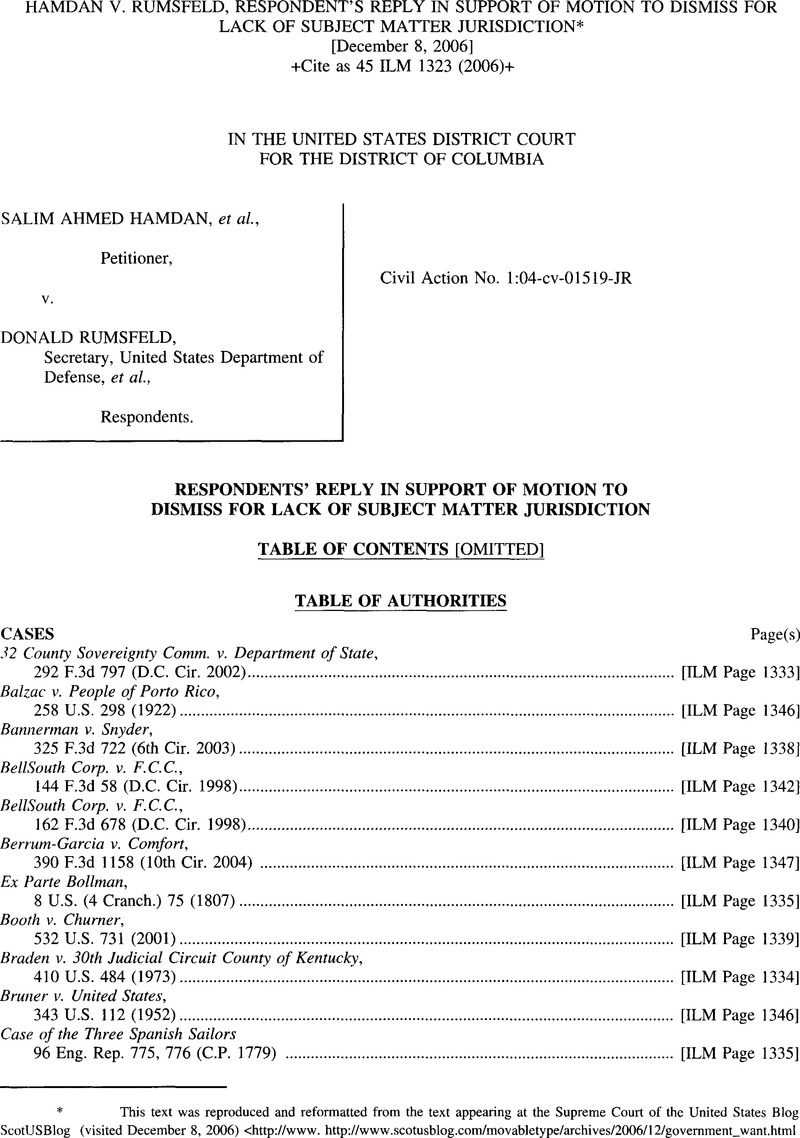

This text was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the Supreme Court of the United States Blog ScotUSBlog (visited December 8, 2006) <http://www.http://www.scotusblog.eom/movabletype/archives/2006/l2/government_want.html>

1 On October 1, 2004, respondents filed an unopposed motion to clarify that the Government was not required to file any material justifying Hamdan's detention as an enemy combatant. See dkt. no. 24. On October 4, 2004, the Court (Green, S.J.) granted the government's motion, stating that respondents were not required to address enemy combatant status issues pending further order of the Court. See p. no. 26.

2 The November 3, 2006 Declaration of Ms. Hecker states that three detainees determined by CSRTs to be “no longer enemy combatants” remain detained at Guantanamo; those three detainees subsequently were released from United States custody, however.

3 It is not clear that petitioner's challenge to his detention as an enemy combatant was even “pending” at the time of the enactment of the MCA. See supra at 5-7. Even if considered pending, however, the MCA divests this Court of jurisdiction, as explained in the text.

4 Petitioner attempts to contrast the language used in section 7 (speaking to “all cases, without exception”) to the language in section 3 of the MCA (enacting 18 U.S.C. § 950j). See Petr's Opp'n at 11 n. 4. In section 3, however, Congress used very similar language to that used in section 7, speaking to “any claim or cause of action” pending on the date of enactment. Just like section 7, the reference to habeas jurisdiction in section 3 is in the first clause regarding the scope of the bar on judicial review, and is not mentioned again in regard to the temporal reach of the provision. The language used in section 7 (“all cases, without exception”) is even broader than the language used in section 3 (“any claim or cause of action”). Thus, there is no “negative inference” to be drawn from section 3.

5 The Hamdan Court recognized that, under the DTA, the D.C. Circuit's exclusive jurisdiction over enemy combatant determinations did apply to pending cases, id. at 2764 (“paragraphs (2) and (3) of subsection (e) are expressly made applicable to pending cases”); id. at 2769 (“Congress here expressly provided that subsections (e)(2) and (e)(3) applied to pending cases”), and the Court left open the question of whether the pending district court habeas challenges brought by the detainees to their detention as enemy combatants would have to be transferred to the Court of Appeal's exclusive jurisdic-tion. Id. at 2769 n. 14.

6 See, e.g., 152 Cong Rec. S10262 (daily ed. Sept. 27, 2006) (Sen. Bingaman) (quoting a letter opposing section 7, “the provision … would strip the federal courts of jurisdiction over even the pending habeas cases”); 152 Cong. Rec. S10357 (daily ed. Sept. 28, 2006) (Sen. Leahy) (“the bill goes far beyond what Congress did in the [DTA]… . This new bill strips habeas jurisdiction retroactively, even for pending cases”); id. at S10403 (Sen. Cornyn) (“once … section 7 is effective, Congress will finally accomplish what it sought to do through the [DTA] last year. It will finally get the lawyers out of Guantanamo Bay. It will substitute the blizzard of litigation instigated by Rasul v. Bush with a narrow DC Circuit-only review of the Combatant Status Review Tribunal-CSRT-hearings”); id. at S10404 (Sen. Sessions) (“It certainly was not my intent, when I voted for the DTA, to exempt all of the pending Guantanamo lawsuits …. Section 7 of the [MCA] fixes this feature of the DTA and ensures that there is no possibility of confusion in the future”); 152 Cong. Rec. H7938 (Rep. Hunter) (daily ed. Sept. 29, 2006) (“The practical effect of this amendment will be to eliminate the hundreds of detainee lawsuits that are pending in courts throughout the country and to consolidate all detainee treatment cases in the D.C. Circuit”); id. at H7942 (Rep. Jackson-Lee) (“The habeas provisions in the legislation are contrary to congressional intent in the [DTA]. In that act, Congress did not intend to strip the courts of jurisdiction over the pending habeas”).

7 The doctrine also requires the statute be fairly read to avoid “serious constitutional problems,” INS v. St. Cyr, 533 U.S. 289, 299-300 (2001), which, as discussed infra II, are not present here.

8 See Lease of Lands for Coaling and Naval Stations, Feb. 23, 1903, U.S.-Cuba, art. III, T.S. No. 418 (6 Bevans 1113) (“1903 Lease”).

9 Indeed, the 1903 Lease prohibits the United States from estab lishing certain “commercial” or “industrial” enterprises over Guantanamo, a restriction wholly inconsistent with control congruent with sovereignty. See 1903 Lease, art. II.

10 The decision of Judge Green in In re Guantanamo Detainee Cases, 355 F. Supp. 2d 443, 461-64 (D.D.C. 2005), extending Fifth Amendment due process rights to Guantanamo detainees should not be followed. See Khalid v. Bush, 355 F. Supp. 2d 311, 320-21 (D.D.C. 2005) (Leon, J.) (aliens detained at Guantanamo are not possessed of constitutional rights). Judge Green's rationale places undue, virtually dispositive weight upon a single, oblique footnote in Rasul that “[p]etitioners' allegations … unquestionably describe ‘custody in violation of the Constitution or laws or treaties of the United States.'” 124 S. Ct. at 2698 n.15. That footnote, however, appended to a paragraph focused entirely on the question of statutory jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 2241 and to a sentence asserting what “[petitioners contended]” for such statutory jurisdic- tional purposes, cannot fairly be read as sub silentio overruling Eisentrager and the other repeated holdings of the Supreme Court that aliens outside sovereign United States territory and with insufficient connection to the United States lack constitutional rights. See Whitman v. American Trucking Ass'n, 531 U.S. 457, 468 (2001) (the Supreme Court “does at … hide elephants in mouseholes”). The reliance in In re Guantanamo Detainee Cases upon the Insular Cases and Ralpho v. Bell, 569 F.2d 607 (D.C. Cir. 1977), as extending fundamental constitutional rights to areas where the United States “technically” is not considered sovereign, see 355 F. 16 Supp. 2d at 461, is likewise misplaced. The territories at issue in those cases were governed essentially as sovereign areas, that is, by Congress pursuant to its constitutional power to “make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States,” U.S. CONST, art. IV, § 3, cl.2, and, thus, are distinct from Guantanamo where the United States does not exercise sovereignty. See Balzac v. People of Porto Rico, 258 U.S. 298, 312-13 (1922); Dorr v. United States, 195 U.S. 138, 142-43, 149 (1904); Ralpho, 569 F.2d at 618-19.

11 Petitioner also argues that the MCA unconstitutionally interferes with core functions of the judiciary because it prevents this Court from enforcing its November 8, 2004 Order and narrows the scope of habeas review in a fashion so as to dictate judicial decision. See Petr's Opp'n at 29-32. This argument is frivolous because in addition to Congress's power to define the proper scope of the writ of habeas corpus, it has long been established that Congress has the power to limit or withdraw the jurisdiction of the federal courts (even as to pending cases). See Gallardo v. Santini Fertilizer Co., 275 U.S. 62, 63 (1927) (ordering dismissal because after the district court had issued an injunction, Congress passed a law “that took away the jurisdiction of the District Court in this class of cases”); Brunerv. United States, 343 U.S. 112, 114, 117 (1952); see also Cobell v. Norton, 392 F.3d 461, 467 (D.C. Cir. 2004) (“For purposes of the rule limiting congressional reversal of final judgments, an injunction is not ‘final’ … ‘[Although an injunction may be a final judgment for purposes of appeal, it is not the last word of the judicial department because any provision of prospective relief is subject to the continuing supervisory jurisdiction of the court, and therefore may be altered according to subsequent changes in the law.'”) (quoting National Coalition To Save Our Mall v. Norton, 269 F.3d 1092, 1096-97 (D.C. Cir. 2001)).

12 See U.S. CONST, art. III, § 1 (“The judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time 21 ordain and establish.”).

13 In fact, Congress specifically intended to preclude all treaty claims in any challenges to CSRT determinations. Section 1005(e)(2)(C)(ii) of the DTA limits judicial review to the question whether the standards and procedures used by the CSRTs are “consistent with the Constitution and laws of the United States,” to the extent the “Constitution and laws of the United States” are applicable. In contrast, the habeas statute permits review of claims that a petitioner is being held “in violation of the Constitution or laws or treaties of the United States.” 28 U.S.C. § 2241(c)(3).

14 Therefore, petitioner's assertion that respondents’ compliance with the prior holding of the Supreme Court in this case amounts to nothing more than “voluntary cessation of a challenged practice,” i.e., the conduct of military commission proceedings against petitioner, see Petr's Opp'n at 27 n.19, has no merit.

15 Thus, petitioner's citation of Rafeedie v. INS, 880 F.2d 506 (D.C. Cir. 1989), see Petr's Opp'n at 28, is inapposite. The court in that case merely engaged in a prudential balancing of the parties’ interests with respect to requiring exhaustion of administrative processes where “Congress did not manifest an intent” to apply an exhaustion requirement. 880 F.2d at 513-18.

16 Cf. Hamdan, 126 S.Ct. at 2771 (“We have no doubt that the various individuals assigned review power under Commission Order No. 1 would strive to act impartially and ensure that Hamdan receive all protections to which he is entitled.”).

17 “[T]he Bill of Attainder Clause not only was intended as one implementation of the general principle of fractionalized power, but also reflected the Framers’ belief that the Legislative Branch is not so well suited as politically independent judges and juries to the task of ruling upon the blameworthi-ness, of, and levying appropriate punishment upon, specific persons.” United States v. Brown, 381 U.S. 437, 445 (1965). Put simply, “[t]he distinguishing feature of a bill of attainder is the substitution of a legislative for a judicial determination of guilt.” De Veau v. Braisted, 363 U.S. 144, 160 (1960).

18 As explained supra II.B.i, petitioner's insistence that enemies captured during armed conflict, and detained by the military as enemy combatants have a right to de novo review of the ruling of the governing military tribunal is wholly unfounded and inconsistent with Supreme Court precedent. Consequently, the MCA does not impose “punishment” because petitioner is not entitled to such sweeping judicial review. In any event, the MCA does not fall within the historical meaning of legislative punishment.

19 Petitioner's reliance on Pierce v. Carskadon, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 234 (1872), is inapposite. Pierce arose in the unique context of the Reconstruction period following the Civil War and involved a statute that deprived non-residents of all access to West Virginia state courts to protect property rights, unless they provided a loyalty oath that they had not supported the Confederacy. Conversely, the MCA involves no similar circumstance and, in fact, expressly creates procedures for judicial review of permissible enemy combatant claims.

20 Indeed, while the MCA jurisdictional provisions need only have a rational basis, as they undoubtedly do, they would survive exacting scrutiny as well.

21 Although petitioner has raised additional arguments, such as that the MCA is an unlawful bill of attainder and that the MCA's jurisdiction-limiting provision violates equal protection, those arguments likewise will be significantly affected by resolution of the question whether alien detainees such as petitioner can invoke the protections of Constitution an issue that is also pending before the Court of Appeals in Al Odah and Boumediene both with respect to the MCA issues and otherwise in the appeals.

22 See Cobell v. Norton, 392 F.3d 461, 467 (D.C. Cir. 2004) (“For purposes of the rule limiting congressional reversal of final judgments, an injunction is not ‘final’ … ‘[Although an injunction may be a final judgment for purposes of appeal, it is not the last word of the judicial department because any provision of prospective relief is subject to the continuing supervisory jurisdiction of the court, and therefore may be altered according to subsequent changes in the law.'”) (quoting National Coalition To Save Our Mall v. Norton, 269 F.3d 1092, 1096-97 (D.C. Cir. 2001).

23 Further, the portion of the November 8, 2004 Order requiring that petitioner be detained in the general detention population at the Guantanamo, “unless some reason other than the pending charges against him requirefd] different treatment,” mustfall given that the other aspects of the Order, upon which the detention constraint was predicated, have been undermined.

24 Alternatively, the Court should transfer this action, to the extent it now challenges petitioner's detention as an enemy combatant, to the Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. See 28 U.S.C. § 1631; Tootle v. Sec'y of the Navy, 446 F.3d 167, 173 (D.C. Cir. 2006) (“[U]nder § 1631, a district court must dismiss or transfer upon concluding that it lacks jurisdiction.”) (emphasis in original); cf. Bermm-Garcia v. Comfort, 390 F.3d 1158, 1162-63 (10 Cir. 2004)(transferring petition for writ of habeas corpus filed in district court by alien challenging INS removal order to court of appeals pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1631 because Congress provided for direct judicial review of such orders in the courts of appeals). As explained supra, the MCA and DTA have withdrawn this Court's jurisdiction to hear the petitioner's claims in this case and vested exclusive jurisdiction, to the extent petitioner challenges his detention, in the Court of Appeals