Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

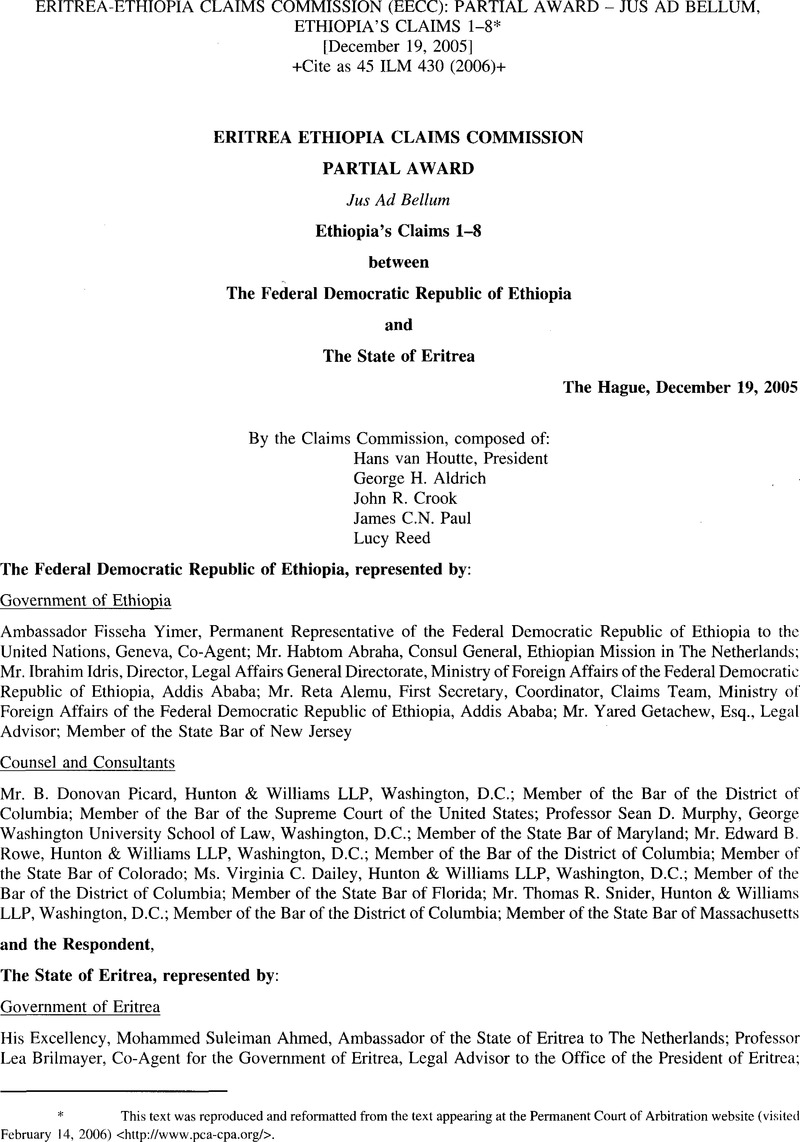

* This text was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the Permanent Court of Arbitration website (visited February 14, 2006) <http://www.pca-cpa.org/>.

1 Both Parties utilized the terminology of jus ad bellum to describe the law governing the initial resort to force between them. At the hearing of this Claim in April 2005, Ethiopia confirmed that it meant by this the use of force contrary to the Charter of the United Nations, June 26, 1945, 59 Stat. p. 1031, 3 Bevans p. 1153 [hereinafter UN Charter].

2 Point 5 of the Commission’s July 24, 2001 letter to the Parties states: The Commission notes the agreement of the Parties that the last sentence of Article 5, paragraph 1 of the Agreement of 12 December 2000, despite its wording, was intended to mean that claims of compensation for all costs of military operations, all costs of preparing for military operations, and all costs of the use of force are excluded from the jurisdiction of the Commission, without exception. Consequently, the Commission shall respect that interpretation of the provision.

3 See, e.g., Partial Award, Central Front, Ethiopia’s Claim 2 Between the the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia and the State of Eritrea (April 28,2004), para. 4 [hereinafter Partial Award in Ethiopia’s Central Front Claims].

4 Decision Regarding Delimitation of the Border between the State of Eritrea and the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission, April 13, 2002, reprinted in 41 I.L.M. p. 1057 (2002).

5 See, e.g., Declaration on Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation Among States in Accordance with the Charter of the United Nations (the “Friendly Relations Declaration“), UN General Assembly Resolution 2625 (XXV) of Oct. 24, 1970, G.A. Res. 2625, U.N. GAOR, 25th Sess., Supp. No. 28, U.N. Doc. A/8028, reprinted in 9 I.L.M. p. 1292 (1970) (“[E]very State has the duty to refrain from the threat or use of force … as a means of solving international disputes, including territorial disputes“); Gaetano arangio-ruiz, the united nations declaration on friendly relations and the system of the sources of international law pp. 104-105 (Sijthoff& Noordhoff 1979); Alfred verdross& bruno simma, universelles volkerrecht p. 905 (Duncker und Humblot 1984); Michel Virally, Article 2: Paragraphe 4, in La charte des nations unies pp. 119-125 (Economica, 2d ed. 1991); Oscar schachter, international law in theory and practice p. 116 (Nijhoff 1991); Peter malanczuk, akehurst’s modern introduction to international law pp. 314-315 (Routledge, 7th rev. ed. 1997).

6 See, e.g., UN Charter, supra note 1, arts. 2(4), 24, 39^2; Ian brownlie, principles of public international law pp. 699-700 (Oxford University Press, 6th ed. 2003); Antonio cassese, international law pp. 296-298, 305-307 (Oxford University Press 2001); Albrecht Randelzhofer, Article 2(4), in The charter of the united nations: a commentary pp. 111-118 (Bruno Simma ed., Oxford University Press 1994).

7 The Parties disagreed regarding the nature of this body. Ethiopia contended that the Parties established a formal commission to address questions relating to the boundary. Eritrea characterized it in less formal terms. In any case, the Parties were engaged in a process of consultations regarding questions related to the boundary before hostilities began.

8 The evidence included references to other high-level contacts and conversations between the Parties in the days prior to May 12, 1998, as well as suggestions of military preparations on both sides of the boundary during this period. However, these matters were not clarified during the proceedings, and the Commission is constrained to act on the basis of the record available to it.

9 Partial Award in Ethiopia’s Central Front Claims, supra note 3, para. 31.

10 Id. at paras. 27-31.

11 In addition to the UN Charter, Ethiopia contended that Eritrea’s actions also violated the Charter of the Organization of African Unity, May 25, 1963, 479 U.N.T.S. p. 39 [hereinafter OAU Charter], as well as several bilateral agreements and customary international law. While the OAU Charter articulates important principles, because of the fundamental role of the UN Charter in relation to the issues presented, this Partial Award does not consider these additional claims in detail.

12 See Hague Convention (III) Relative to the Opening of Hostilities, Oct. 18, 1907, 36 Stat. p. 2259, 1 Bevans p. 619.