This special section can be seen as part of a tradition of special issues of International Labor and Working-Class History (ILWCH) and the International Review of Social History (IRSH) that comment on the state of the field of Ottoman labor historiography, describe its achievements and caveats, and set the agenda for future research. The late Donald Quataert, pioneer of Ottoman labor history, started this tradition in 2001, when he edited this journal's special issue Labor History in the Ottoman Middle East, 1700–1922. Footnote 2 Touraj Atabaki and Gavin D. Brockett followed in 2009 with their special issue of the IRSH Ottoman and Republican Turkish Labour History. Footnote 3 With the current special section we aim to add to this tradition. In the first section of our introduction, we will provide a brief overview of the main conclusions of the first two special issues, and shed some light on what happened after 2009. In the second section, we will discuss what we hope to add: an approach based on the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations that can help us to reconstruct the development of labor relations in the Ottoman Empire and its successor states. We describe this approach and results of the project worldwide so far. The third section starts with a brief overview of the Ottoman/Turkish Republic branch of the Collaboratory that focuses mainly on Anatolia and its views on sources and methodologies. It will describe the article by Karin Hofmeester and Jan Lucassen in this special section as result of these activities and the articles by Hülya Canbakal and Alpay Filiztekin and İrfan Kovidas and Yahya Araz as results of other projects that link up perfectly with the Collaboratory approach. Special attention will be devoted to the town of Bursa and its hinterland from the sixteenth until the twentieth century, putting the developments in this city in the broader perspective of Ottoman-Anatolian and Turkish labor history.Footnote 4

Labor history in the Ottoman Empire

In his introduction to the IWLCH special issue, Donald Quataert sketched how the subfield of labor history progressed in the 1970s when the focus of many labor historians was on the development of the working class, of workers organized in guilds and trade unions, with a special stress on worker's relationships with the state.Footnote 5 Of course, this was also the case in many non-Ottoman labor historiographies. However, the Ottoman case was characterized by features specific for the area, the most important one being the highly influential statist and nationalist narrative of the Ottoman successor nation-states. This narrative determined the focus on the role of the state in the formation of the working class and working-class consciousness. The narrative in itself was influenced by the “modernization” paradigm that argued that change in the Ottoman Empire that came from the West inspired—for example—Turkish reformers to make the new Turkish Republic a “modern,” “secular” nation-state, in complete contrast to the “backward” policies of the rulers of the Ottoman Empire. The paradigm created an artificial watershed between the Ottoman and the post-Ottoman period that made labor historians discard the Ottoman period and—as Quataert later added—made them overlook the many continuities in the history of labor and labor relations in the Ottoman and post-Ottoman period.Footnote 6

Atabaki and Brockett in their introduction further elaborated upon this modernization paradigm and concluded that the focus in Ottoman and Turkish labor history on factory workers was also caused by it, as modernization was supposed to lead, inevitably, to industrialization and urbanization, and thus the development of a proletariat.Footnote 7 In the second phase of labor historiography, as both Quataert and Atabaki and Brockett showed, the focus shifted to workers in action: in strikes and in socialist and other left-wing movements that tried to enter the political arena. As a consequence, the studies written in the 1970s and 1980s focused on class conscious, politically active factory workers, who in reality only formed a small part of the total working population. In the 1990s, various steps were taken in broadening the category of workers to include peasants, weavers, and miners.Footnote 8 In these studies and also in the works that followed in the first decade of the twenty-first century, great steps forward were taken in extending the researched period (Ottoman and post-Ottoman), as well as the type of work and worker that were researched.

Quataert's introduction ended with a plea for looking at regional differences and locally distinctive cultures, local labor traditions, and market conditions, whereas at the same time he reminds the reader at the start of his text that even though Ottoman workers had many different mother tongues they all rested in the administrative hand of one Ottoman state so it makes sense to speak of an Ottoman labor history. He advocated for the study of unorganized workers in small scale work sites, female unorganized work, also in the country side, and chain migration. He also advocated for a differentiated approach to the role of religion and ethnicity in the analysis of labor division, a traditional theme in Ottoman labor history. Though many of the above mentioned themes and approaches were dealt with in the articles in Quataert's special issue, they focused on Istanbul and Cairo, two main capitals, so they were limited in geographical scope. Also, most articles dealt with the nineteenth century, with an exception of Fariba Zarinebaf-Shar's article on the role of women in the urban economy of Istanbul that starts in 1700. This special issue ends where the Ottoman Empire ends: in 1922.

Atabaki and Brockett actively bridged the gap between Ottoman and post-Ottoman labor history by explicitly combining Ottoman and Republican Turkish Labor History in one special issue. Though they focus only on one part of the Ottoman Empire (Anatolia and eastern Trace) and its successor state, continuity in Ottoman and post-Ottoman labor history in general is stressed.Footnote 9 Furthermore, they invite scholars to depart from the “old” institutional labor history and apply insights from new labor history, focusing on gender, ethnicity, and the structure of households, as well as informal social and political relationships. New topics, such as the co-existence of compulsory and free wage labor, in this case in the Zonguldak coalfields, as well transnational aspects of labor history, such as Ottoman migrants in the United States and workers (including child laborers) in Western department stores in Istanbul, are well represented in this special issue. Moreover, as one of the first, Atabaki and Brockett stressed the necessity to integrate Ottoman and post-Ottoman labor history into global labor history. Various scholars have taken this plea to integrate Ottoman labor history into global labor history to heart, and in 2011 at Istanbul Bilgi University, an international conference was organized entitled Working in the Ottoman Empire and in Turkey: Ottoman and Turkish Labour History within a Global Perspective. As the report by M. Erdem Kabadayı and Kate Elizabeth Creasey in this journal shows, the connection between the “local” and the global was not always explicitly mentioned in the papers presented there. However, the topics and the approaches show a much broader interpretation of work and labor history than ever before, which makes the integration of these results into the bigger picture of global labor history possible.Footnote 10 Various presentations touched upon unfree labor (amongst others in the military and in rural areas), the link between labor relations in agricultural production and industrial production (both determined by urban consumption patterns, including the relation between wage labor and sharecropping as well as the role of proto-industrialization), and labor migration and various forms of remuneration. Both Anatolia, the Balkan, and the Arab countries are touched upon in the papers.Footnote 11

The latest overview of labor history and historiography in the Ottoman Middle East and Modern Turkey written by Gavin Brockett and Özgür Balkılıç teaches us that new research is focusing on various specific regions (including the provinces) and time periods of the Ottoman Empire, also including the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.Footnote 12 These studies do include topics like work and gender, work and ethnicity, as well as labor migration. They also look at various forms of labor, including slavery, corvée labor, convict labor, and other forms of forced labor, as well as the relation between human and animal labor. The work processes, labor conditions, gender, and ethnic identity of various groups of industrial workers still form a theme in recent works on the final years of the Ottoman Empire, though now with a focus on how workers perceived the large scale economic, political, cultural, and social transformations that impacted their lives but also how they shaped these transformations. The still less well developed labor histories of republican Turkey stress the importance of workers as social actors in political and social events. Even though most of these studies concentrate on the industrial labor force, a number of studies focus on agricultural labor and the position of small holders in an increasingly marketized rural economy.

Taking all these considerations together, we may conclude that this is a good moment to build further on an Ottoman and post-Ottoman labor history that focuses on work, workers, and labor relations in their broadest sense. This would mean: including all types of work in farms, factories, households, armies, and religious and administrative institutions done by men, women, and children under all possible forms of labor relations from slavery to free wage labor, in as many localities as possible. These localities should then be followed over a long period, both in the Ottoman as well as in the post-Ottoman period, keeping an eye on local specificities and at the same time trying to reconstruct a bigger picture that could be compared and connected with worldwide developments in labor and labor relations. The Global Collaboratory approach could be one way of achieving part of this goal.

The Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations 1500–2000

To better understand the diverse forms of labor relations worldwide, the International Institute of Social History (IISH) in Amsterdam set up the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations. This project aims to draw up a worldwide inventory of all types of labor relations, in all their facets and combinations, in different parts of the world at five cross-sections in time: 1500, 1650, 1800, 1900 (and, for Africa, 1950), and 2000.Footnote 13 The first phase of this project (2007–2012) consisted of data-mining.Footnote 14 The second phase of the project sets out in search of explanations for shifts in labor relations, as well as for the possible patterns observed therein. Causes and consequences of shifts in labor relations are explored in a series of dedicated workshops by looking in-depth at possible explanatory factors, such as the role of the state, demography, and family patterns and economic institutions.Footnote 15

The Collaboratory departs from a comprehensive definition of work as provided by the sociologists Charles and Chris Tilly: “Work includes any human effort adding use value to goods and services.”Footnote 16 To develop a new and encompassing classification of labor relations, as necessary for long-term global comparisons, we depart from the following assumption: labor relations define for or with whom one works and under what rules.

To start with the first part of this assumption: People do not work alone. Nor do they work only for themselves. In the first place, each individual works for the larger part of their life for a family or household, defined as a group of kin who pool their income and mostly live and eat together. Taking the individual as a nucleus, we distinguish the family or household as the first shell. Often tax officials and census takers departed from the family or household, like the temettuat survey conducted in the Ottoman Empire in the 1840s.Footnote 17 Sometimes groups of households share tasks, in which case we speak of communities. When communities share a form of government whose leadership has the power or mandate to establish and maintain rules pertaining to labor, we speak of a polity. When we call the family/household (or several, united in a community) the second shell, the polity, logically forms the third shell, and the market may be conceived as the fourth. In a society based on production for the market, individuals as part of the fourth shell can also produce indirectly for the market in non-market institutions, like state enterprises, armies, or bureaucracies, or in monasteries, etc.Footnote 18 This brings us to the following taxonomy:

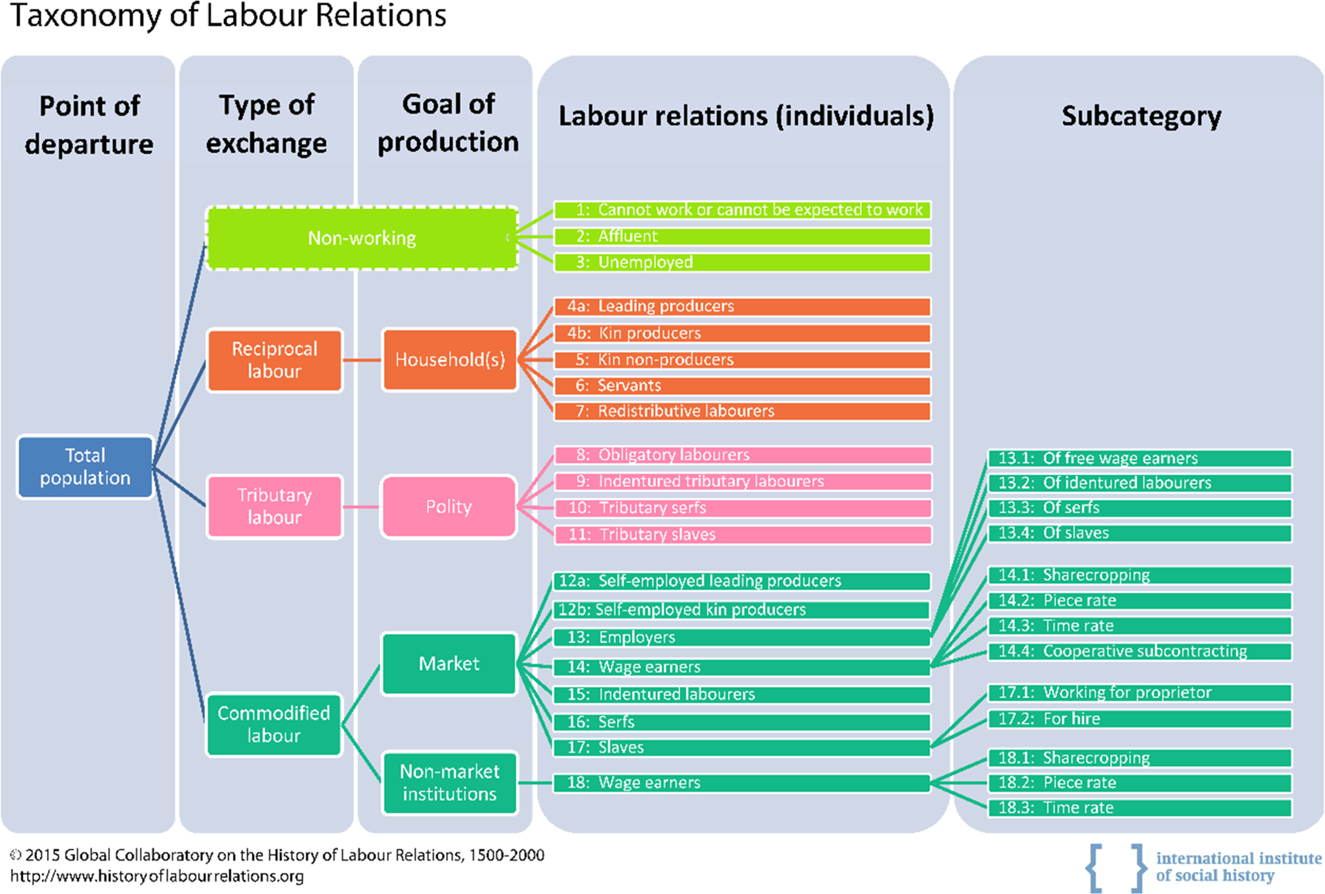

Figure 1: Taxonomy of labor relations

In order to classify the total population (column 1) according to this taxonomy, we applied the following logic. We stress that this taxonomy should primarily be considered a tool to characterize individuals (column 4). The scheme should therefore be read from right to left and this enables us to shed some light on the character of that society within a given place and period.

The taxonomy distinguishes between persons that are able to work and those unable to work (the category non-working in our taxonomy). This forces one to be aware of what work is and to cover the entire population, thus explicitly also taking working women and children into account. Next, in column 2, it distinguishes between the three types of exchange in organizing the exchange of goods and services, including work. These types of exchange are linked up with the three levels of analysis listed in column 3, which reflect the target of production: the household and/or community, the polity, or the market. The principles under which this exchange takes place are reciprocity (work done for other members of the same household or a group of households that form a community), tribute giving (work based on obligations vis-à-vis the polity), and market exchange in which labor is “commodified” (i.e., where the worker or, in the case of unfree labor, the owner of the worker, sells their means of production or the products of their work). The second part of our definition of labor relations—under what rules do people work—is partially captured in column 3 as it gives the context of rules, but they are expressed more detailed in column 4, where the labor relations of individuals are indicated, including the type of relation and indentured, servile, slave, and wage labor. (For the various definitions of labor relations, see Appendix 1.)

The preliminary outcomes of this project suggest that at least for the last five centuries, the share of the population engaged in commodified labor increased at the expense of reciprocal labor and tributary labor.Footnote 19 Commodified labor started earlier than expected, but at the same time reciprocal labor lasted longer than previously assumed. This can be explained by another important finding that, from early on, many individuals and households pooled various types of labor relations; combining reciprocal labor with commodified labor or vice versa, to name just one example.Footnote 20 Often, shifts in labor relations manifest themselves as shifts in combinations of labor relations. Within the category of commodified labor, we see a shift from self-employment to wage labor. This was not a linear development; the most recent example are the many regions in the world that experienced decreases in wage labor in the twenty-first century. What drove these developments? That is what the Collaboratory project hopes to answer. To collect data on labor relations and to interpret and analyze these data, the Collaboratory organizes series of workshops where scholars from all over the world meet and share data.Footnote 21

Labor relations in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey: Results from the Collaboratory and other projects

For the collection of data on the Ottoman Empire, we organized four workshops in the period from 2009 to 2012.Footnote 22 During these workshops, possible sources and methodologies were discussed and the idea was developed to follow a series of Ottoman towns and their hinterlands over time. These towns and surrounding regions should be seen as dots on a map, keeping in mind the regional differences between the dots and at the same time keeping the framework of the Ottoman Empire as context. One of the possible sources discussed were tax registers. Since multiple series were produced in the whole of the Ottoman Empire—though no series covered the whole Empire—over a long period of time they are one of the few sources that can provide us with basic data we can use to reconstruct labor relations.Footnote 23 This has turned out not to be an easy task. Although the so-called temettuat registers are promising, their conversion into labor relations cannot be performed in a straightforward way. Even the first industrial censuses of the late Ottoman Empire (held in 1913 and 1915, published in 1917) and the earliest population and industrial censuses, which were undertaken by the Turkish Republic in 1927, as well as the population census of 1935, are hard nuts to crack.Footnote 24

This set of articles on Anatolia is a first attempt to gain an idea of labor relations in the Ottoman Empire for an earlier period and to put them in a long term perspective. They will not enable us to come up with a precise overall picture but the framework for such a task becomes clearly visible, we believe. The first article of this special section by Karin Hofmeester and Jan Lucassen, “Ottoman tax registers as a source for labor relations in Ottoman Bursa” shows how tax registers may be used to reconstruct labor relations, taking the province of Bursa, its towns, and its surrounding villages in the late fifteenth and sixteenth century as a case study. Based on our analysis of the tahrir tax registers of the town of Bursa in the period 1487–1521, we see a decrease of self-employed people and their dependents, and at the same time an increase of wage labor for the market. This conclusion is based on our interpretation of the number of renter households—that we considered as wage-earners—and a decrease of the number of owner households—interpreted as self-employed people. Perhaps this shift could be explained by the 1512–1520 crisis in silk manufacturing and trading as a consequence of the war between the Ottoman Empire and Persia. At the same time—using additional sources—we assumed that in the period 1487–1521 there was a steady percentage of slaves and wage workers for the state. From 1522 to 1573, a new (though relatively small) growth of small independent producers was possible at the expense of both wage labor in the commercial sector and of slavery. Again an explanation for this shift can be found in the important silk industry. After 1550, this industry diminished and larger manufacturers may have started to leave, leading to a smaller number of wage earners and leaving room for self-employed producers. At the same time, the growing population of the city went hand in hand with an increasing bureaucratization of the administration of the Ottoman Empire, and thus a growing number of civil servants, working for wages for the state.

For the later periods, we lack such systematic sources as the tax registers, though based on our interpretation of data on various economic developments, we perceive some general trends. After 1600, a shift took place in the silk industry when next to Persian silk local raw silk was used in manufacturing. This cheaper silk cloth was being produced via the putting out system, and slave labor in the silk industry was replaced by cheap free labor, —including women's work—recruited via the putting-out system, without however making wage labor insignificant. Wage work would increase again over the course of the nineteenth century.

In contrast to urban Bursa, the countryside shows more important shifts in the second period (1521–1573) than in the first period (1487–1521). This may be related to the strong demographic growth of the town and its surrounding village hinterland in the second period. This led to an increase of the number of landless households and an increase of wage earners accompanied by a decrease of the self-employed and their dependents. For the seventeenth century, it is impossible at this moment to provide approximate proportions. Still, we tentatively would like to suggest that there seems to be a tendency of ownership shifting from small to medium proprietors and above medium urban ones who invested in the promising countryside. This would then lead to an increase of rural wage workers. At the same time, the overwhelming majority of the grown-up rural population must have been independent producers for the market. In a very general way, we may conclude that in the seventeenth, and perhaps also in the eighteenth century, about three quarters of all households may be characterized as independently producing for the market and one quarter as wage earning, whereas hardly any rurals were employers (these lived in the town) or slaves. Later on, but possibly only from the early nineteenth century onwards, farm size diminished. This low average size—by no way excluding wage labor, especially at seasonal peaks—suggests a return to the situation in the sixteenth century, although the available figures certainly cannot be compared in a straightforward way.

An important addition to the literature on Bursa is the second article of this special section by Hülya Canbakal and Alpay Filiztekin “Slavery and decline of slave-ownership in Ottoman Bursa, 1460–1880,” that offers the first long-term analysis of slave holding and prices, as well as of the demand for slaves, not only as articles of luxury consumption but as laborers in an Ottoman region. The analysis by Hülya Canbakal and Alpay Filiztekin of slave-ownership, as captured in the probate inventories of the region of Bursa from 1460 to 1880, shows that slave-ownership seems to have been mainly an urban phenomenon in Bursa. Their data show a peak of slave-holding in the fifteenth century, which is in many inventories linked to luxury textile manufacture. Slave-ownership declines slowly in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and rapidly in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. This same trend can also be found in the number of slaves per owner and the amount of wealth spent on slaves. What Canbakal and Filiztekin also show is that slave prices rose until the early eighteenth century, and then a long term downward trend started, especially after the mid eighteenth century. This downward trend can partially be explained by the background of the slaves (the number of Eurasian slaves declined, whereas the share of African slaves increased) but also by possible changes in the labor market and changes in labor relations. The authors suggest that there is a relation between an increase in wage labor and declining wages on the one hand, and a decrease of slave ownership but also of slave prices on the other. This could happen because bonded labor and free labor at that time were substitutable in Bursa. Also, the number of people that could afford to own slaves declined, though not enough to explain the downward trend of slave prices. The demand for slave labor clearly declined since the mid-eighteenth century.

The third article by İrfan Kovidas and Yahya Araz, “In between market and charity: Child domestic work and changing labor relations in nineteenth-century Ottoman Istanbul,” addresses a central issue of the Collaboratory: at what age do children start to work—one of the main indicators for which part of the population is not working. But it does more, as it also discusses the type of work, whether it is for the household or for the market, as well as the question at what age girls marry and to what extent that implies a change of their labor relations. The article shows that the nature and perception of child domestic work—as reflected in legal contracts between the children and the families they would work for—changed: from work shaped by the concept of charity and economic interests to more formalized wage labor, a shift from reciprocal to commodified labor that took place in the course of the nineteenth century. During the nineteenth century, we see a clear commodification of domestic child labor. In the first half of this century, a minority of the contracts explicitly stated which part of the wage was to be spent on subsistence and which part should be set aside for the child, whereas in the second half of the century the majority of contracts contained explicit statements on the proportion of wage that should be set aside for the children. Contracts were clearly standardized and child labor became more commodified.

How to frame these local data from the late fifteenth to the late nineteenth in a long-term and wider Ottoman and Turkish history up till now? It was only after the First World War and the great population exchanges afterwards that national figures for Turkey became available. The earliest occupational censuses which provide more or less direct information on labor relations in Turkey date from 1950 and 1955 (see Appendix 2 Table 1 and 2). Knowing the rough proportions around the middle of the century, we can go back one step further to the very detailed 1935 occupational census, analyzed for the Collaboratory by Gavin BrockettFootnote 25 (see Appendix 2 Table 3). On the one hand, they allow us also to compare Bursa city and Bursa Province with the national overview; on the other hand, they do not allow to distinguish between the commodified labrels 12a and b, 13 and 14. For 1935, the differences between Bursa province and Turkey as a whole are negligible. However, Bursa town shows a few interesting deviations from the provincial and national pattern. First, there is the high percentage of those not working. From the details provided in the report written by Brockett it is clear that this is nearly totally due to the high number of students in Bursa town (5,642 male and 3,828 female students of fifteen and older). For 1927, three censuses are available: one on the population, one for industry, and one for agriculture.Footnote 26 The Industrial Census of 1927 registers only 260,980 persons, and therefore cannot be easily used to confirm (or, for that matter, to contradict) a similar low representation of wage laborers as in the period 1935–1955. It nevertheless is clear that the far majority of industrial workers were employed in small firms as in this same census we find 309,988 industrial workers in 21,883 establishments employing more than four workers, or on average fifteen workers per factory. This is the classical core of the proletariat, but it is with 2.29 percent only a tiny part of the population.Footnote 27

The next question is whether we can find many wage laborers among the agricultural population, or whether it mainly consists of small peasant farmers, relying mostly on the labor of household members. In that same year, Turkey still was predominantly agricultural as demonstrated by the Agricultural Census of 1927, stating that out of a total population of 13,517,385 persons no less than 9,145,008, comprising 1,751,239 families (or 5.2 family members on average), i.e., over two thirds, were engaged in agriculture. Unfortunately, these figures prevent us from confirming or falsifying the labor relations picture obtained for 1935–1955. All we can say is that they do not contradict each other. Nevertheless, indirect evidence suggests that by and large primary labor relations in 1927 will not have differed too much from those eight years later. In both years, overall there were not many agricultural laborers.Footnote 28 Of course there are differences between the period 1923–1928, when agriculture flourished, and 1935, after the economic crisis had hit Turkey and especially its agriculture severely. Many peasants became underemployed because they thought it pointless to grow products that could be sold only at a loss. Some men also sought temporary employment in railway construction and occasional employment in the towns, but there was no massive permanent outflow of peasants to the cities. That started only really in the 1950s.Footnote 29 In sum, nevertheless the economic world crisis we may not expect major shifts in labor relations between 1927 and 1935.

By combining the data for 1935, 1950, and 1955, and by supposing that the proportion of wage laborers will not have been substantially less in 1935 than it was in 1950 (a mere 5 percent) and after some corrections to the census data, we may obtain the fullest possible picture for the first half of the twentieth century that can be complemented with data on the latter part of the twentieth century (see Table 1 below).

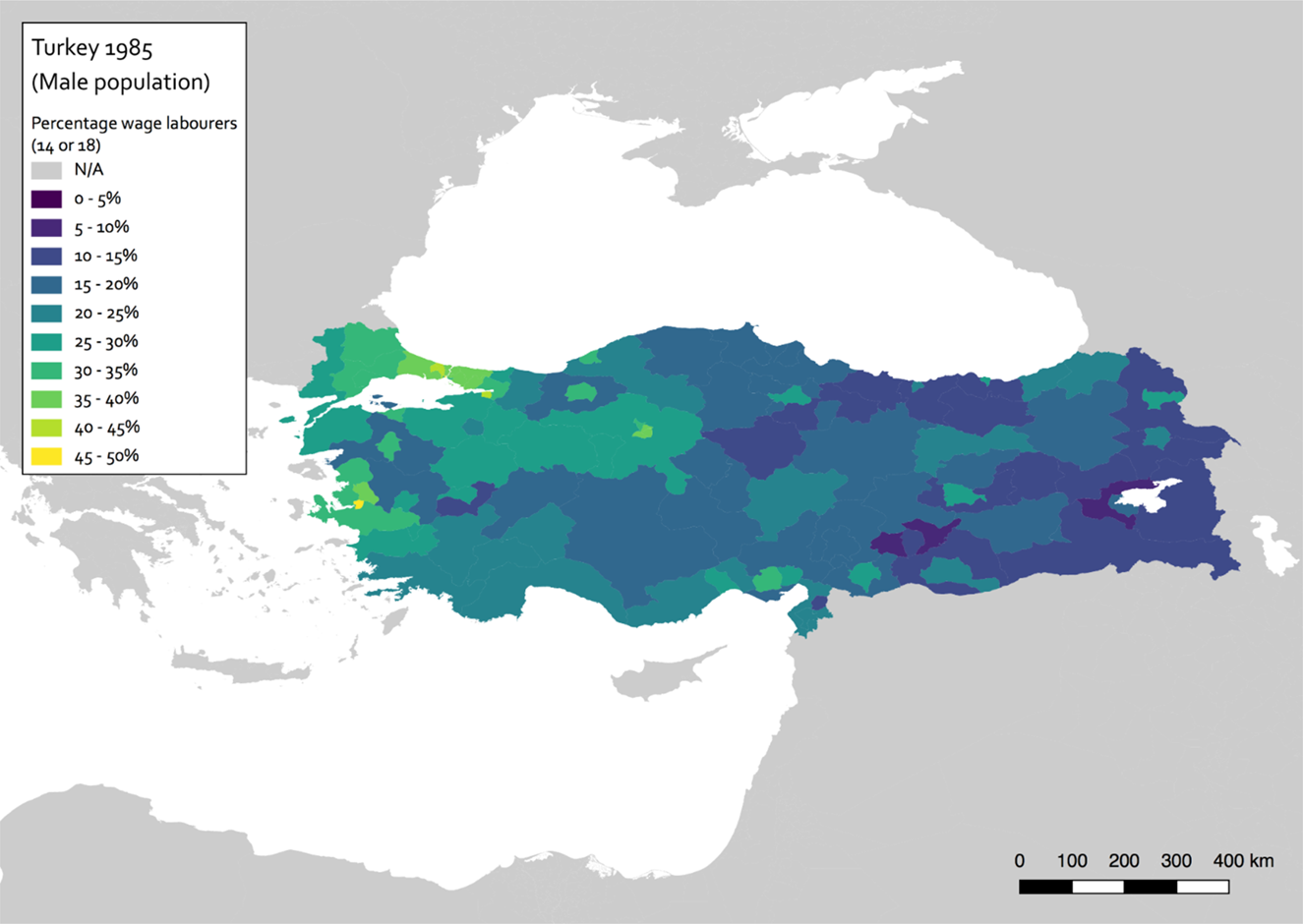

For the years 1985, 1990, and 2000, we have individual data that is part of the samples taken from the censuses of those years taken by IPUMS (see Table 5 of Appendix 2). Our colleagues Rombert Stapel and Richard Zijdeman developed an algorithm that attributes labor relations to individuals based on the different variables we find in the digitized censuses, including age, class of worker, employment status, whether someone was considered in the labor force, their occupation, and whether they lived on a farm.Footnote 30 This algorithm makes it easier to make a distinction between labor relation categories 12b and 14: the kin producers who worked in the family firm and those working for wages. Disadvantage is that the non-working population is harder to subdivide into categories 1, 2, and 5. For 2000, we can compare the IPUMS data with the data Brockett distilled from the aggregate census data. Brockett's data does make a distinction between labrel 1 and 5 and between the labrels 14 and 18. For 2000, we adapted the IPUMS data for the above mentioned categories, based on his analysis.

Table 1: Labor relations in Turkey from 1935 to 2000 (based on Tables 1–5 in Appendix 2).

The regional distribution (regions being larger than the provinces, so Bursa province is here part of a larger region, see Map 1 and 2 in Appendix 2) of wage laborers according to the IPUMS data for 1985, 1990, and 2000 show one major change in developments over these fifteen years and that is a steady increase of female wage work in urban areas.Footnote 31 These data also demonstrate, secondly, that in 1985 the representation of wage laborers (labrel 14 and 18) in this urban area in North Western Anatolia is 17.8 percent of the total population: 28.9 percent of the male and 6.2 percent of the female population. This deviates from the national average: in 1985, 24.4 percent of the male and 4.3 percent of the female population, or 14.7 percent of the total population was engaged in wage labor as a primary source of income. What we finally see is a country wide increase of wage work from the data here presented for the mid-1950s.

Where Bursa seems to be more inclined to wage work in the sixteenth and seventeenth century than the Ottoman Empire as a whole, this specific position does not become clear from the 1935 census which may also have to do with the nature of the source. It does reappear in the censuses of 1985, 1990, and 2000.

To sum up, long term trends in labor relations in the Ottoman Empire show a rather early—and not dissimilar to other parts of Eurasia—emergence of commodification in certain centers from at least the late Middle Ages.Footnote 32 Bursa provides a good case where dependency on market prices and opportunities for silk self-employment rises and diminishes vis-à-vis wage labor and slave labor. The latter, however, becomes rather insignificant from the seventeenth century onward.

Another economic center, Istanbul, shows that in the nineteenth century child laborers turned into wage workers. From 1935 onward, we have Turkish national data for the first time. In this period, commodified labor is predominant, in which self-employment as a primary labor relation prevails until the 1960s. The cursory shift to wage labor, however, has been a gradual one, in which wage labor as secondary labor relation can be identified already from the 1930s as shown by the studies of Hatipoğlu, Stirling, and others.Footnote 33 This squarely fits in a broader Eurasian pattern although more studies are needed, especially for the eighteenth century and with a focus on regional variation.

Appendix 1: Definitions of Labor Relations

Non-working:

As a starting point for each geographical unit and cross section, we take the entire population and subsequently determine what part is not, as a rule, working, and, consequently, what part is working (these “calculations” will often be based on estimates rather than precise data). The non-working population is divided into the following three categories:

1. Cannot work or cannot be expected to work: those who cannot work, because they are too young (≤ 6 years), too old (≥ 75 years), disabled, or are studying.

2. Affluent: those who are so prosperous that they do not need to work for a living (renters, etc.), and consequently actually do not work. This also goes for their spouses, if all their productive and reproductive tasks are taken over by servants, nannies, etc. There are, of course, affluent people, owners of big companies, who are wealthy enough to stop working but nevertheless choose to continue to work. If they are employers, these people should be assigned to labor relation 13 instead of 2.

3. Unemployed: although unemployment is very much a nineteenth- and, especially, twentieth-century concept, we do distinguish between those in employment and those wanting to work but who cannot find employment.

Working:

Reciprocal labor:

Persons who provide labor for other members of the same household and/or community are subsumed within the category Reciprocal labor.

Within the household:

4a. Leading household producers: heads of self-sufficient households (these include family-based and non-kin-based forms). Self-subsistence can include small market transactions, but only if most (at least 80 percent) of total household income is earned through self-subsistence labor. Heads of households have labor relation 4a.

4b. Household kin producers: subordinate kin, including spouses (men and women) and children of the above heads of households, who are mainly self-subsistent and who contribute to the maintenance of the household by performing productive work for that household.

5. Household kin non-producers: subordinate kin, including spouses (men and women) and children of heads of households, who can support the household (under either reciprocal or commodified labor relations). These spouse and kin dependents are free from productive work, but they contribute to the maintenance of the household by performing reproductive work for the household, i.e., especially child rearing, cooking, cleaning, and other household chores. In all other cases, spouses and kin producers in the categories named have income-generating activities essential for the survival of the household, i.e., labor relations 12a, 12b, 13, 14, or 18, and will have one of these labor relations themselves.

6. Reciprocal household servants and slaves: subordinate non-kin (men, women, and children) contributing to the maintenance of self-sufficient households. This category does not include household servants who earn a salary and are free to leave their employer of their own volition (i.e., labor relation 14), but it does include servants in autarchic households, monasteries, and palaces. They may work under all shades of conditions, from enforcement (including pawnship) to a desire to receive patronage. These conditions may change from one generation to another.

Within the community:

7. Community-based redistributive laborers: persons who perform tasks for the local community in exchange for communally provided remuneration in kind, such as food, accommodation, and services, or a plot of land and seed to grow food on their own. Examples of this type of labor include working under the Indian jajmani system, hunting and defense by Taiwanese aborigines, or communal work among nomadic and sedentary tribes in the Middle East and Africa. In the case of the jajmani workers in South Asia, hereditary structures form the basis of the engagement, while in parts of Africa or Taiwan the criteria for fulfilling community-based labor are gender and age (in Taiwan, for example, males between six and forty).

Tributary labor:

Persons who are obliged to work for the polity (often the state, though it could also be a feudal or religious authority). Their labor is not commodified but belongs to the polity. Those workers are included in the category Tributary labor.

8. Obligatory laborers: those who have to work for the polity, and are remunerated mainly in kind. This category includes those subject to civil obligations (corvée laborers, conscripted soldiers, and sailors) and work as punishment, i.e., convicts. Yet the obligatory work can also be an entitlement that enjoys middle or high social standing, such as the European or Indian nobility, the samurai in Japan, or banner people in Qing China.

9. Indentured tributary laborers: those contracted to work as unfree laborers for the polity for a specific period of time to pay off a debt or fine to that same polity.

10. Tributary serfs: those working for the polity because they are bound to its soil and bound to provide specified tasks for a specified maximum number of days, for example, state serfs in Russia.

11. Tributary slaves: those who are owned by and work for the polity indefinitely (deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to receive compensation for their labor). One example is forced laborers in concentration camps.

Commodified labor:

Work done on the basis of market exchange in which labor is “commodified,” i.e., where the worker or the products of his work are sold. The category Commodified labor is subdivided into those working for the market and those working for public institutions that may nevertheless produce for the market (though not for the gain of private individuals).

For the market, private employment:

12a. Self-employed leading producers: those who produce goods or services for the market (for example, peasants, craftsmen, petty traders, transporters, as well as those in a profession) with fewer than three employees, possibly in cooperation with).

12b. Self-employed kin producers: household members including spouses and children who work together with self-employed leading producers who produce for the market. All members of a family working under a putting-out system should be counted as self-employed producers.

13. Employers: those who produce goods or services for market institutions by employing more than three laborers. The number after the dot is an attribute that says something about the freedom or unfreedom of the employees.

13.1 Employers who employ free wage earners.

13.2 Employers who employ indentured laborers.

13.3 Employers who employ serfs.

13.4 Employers who employ slaves.

14. Market wage earners: wage earners (including the temporarily unemployed) who produce commodities or services for the market in exchange mainly for monetary remuneration. A subdivision is made by type of remuneration.

14.1 Sharecropping wage earners: remuneration is a fixed share of total output.

14.2 Piece-rate wage earners: remuneration at piece rates.

14.3 Time-rate wage earners: remuneration at time rates

14.4 Cooperative subcontracting workers at piece rates.

15. Indentured laborers for the market: those contracted to work as unfree laborers for an employer for a specific period of time to pay off a private debt. They include indentured European laborers in the Caribbean in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and indentured Indian, Chinese, and Japanese workers after the abolition of slavery.

16. Serfs working for the market: those bound to the soil and bound to provide specified tasks for a specified maximum number of days for private landowners, for example, serfs working on the estates of the nobility.

17. Slaves who produce for the market: those owned by their employers (masters). They are deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to receive compensation for their labor. Here we do not distinguish between the different ways individuals may become enslaved (sale, pawning, etc.). We do, however, differentiate between:

17.1 Slaves working directly for their proprietor, for example productive work by plantation slaves, and domestic slavery in households producing for the market.

17.2 Slaves for hire, for example for agricultural or domestic labor (as a rule, they may keep a small part of their earnings, while the largest part goes to the owner).

For non-market institutions:

18. Wage earners employed by non-market institutions (that may or may not produce for the market), such as the state, state-owned companies, the Church, or production cooperatives, who produce or render services for a free or a regulated market. A subdivision is made by type of remuneration:

18.1 Sharecropping wage earners: remuneration is a fixed share of total output.

18.2 Piece-rate wage earners: remuneration at piece rates.

18.3 Time-rate wage earners: remuneration at time rates.

Appendix 2: Turkish labor relations in the twentieth century

In the 1950 census, we find the erroneous indication employer (müesseselerde veya başkasının yanında), which can be translated as “at institutions or as with/under someone” even for over 11,000 children aged 5–9. As the employees are missing and the translation clearly does not mean “employer,” we suppose that here the latter category is meant but falsely translated as employer in the census. This is confirmed if we compare these figures with those for five years later. The category “unknown” probably refers to persons unable to work. For the rest the attribution of labor relations may be done in a rather straightforward way.

Table 1: Labor relations in Turkey in 1950

Table 2: Labor relations in Turkey in 1955

Table 3: Labor relations in percentages for Turkey and Bursa province, town and countryside in 1935.

Table 4: Development of labor relations 1935–1955

Table 5 Development of labor relations in Turkey in 1985–2000

Figure 2, Map 1. Made by Rombert Stapel. Based on Minnesota Population Center. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International: Version 7.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2018. https://doi.org/10.18128/D020.V7.0.

Figure 3, Map 2. Made by Rombert Stapel. Based on Minnesota Population Center. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International: Version 7.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2018. https://doi.org/10.18128/D020.V7.0.