Article contents

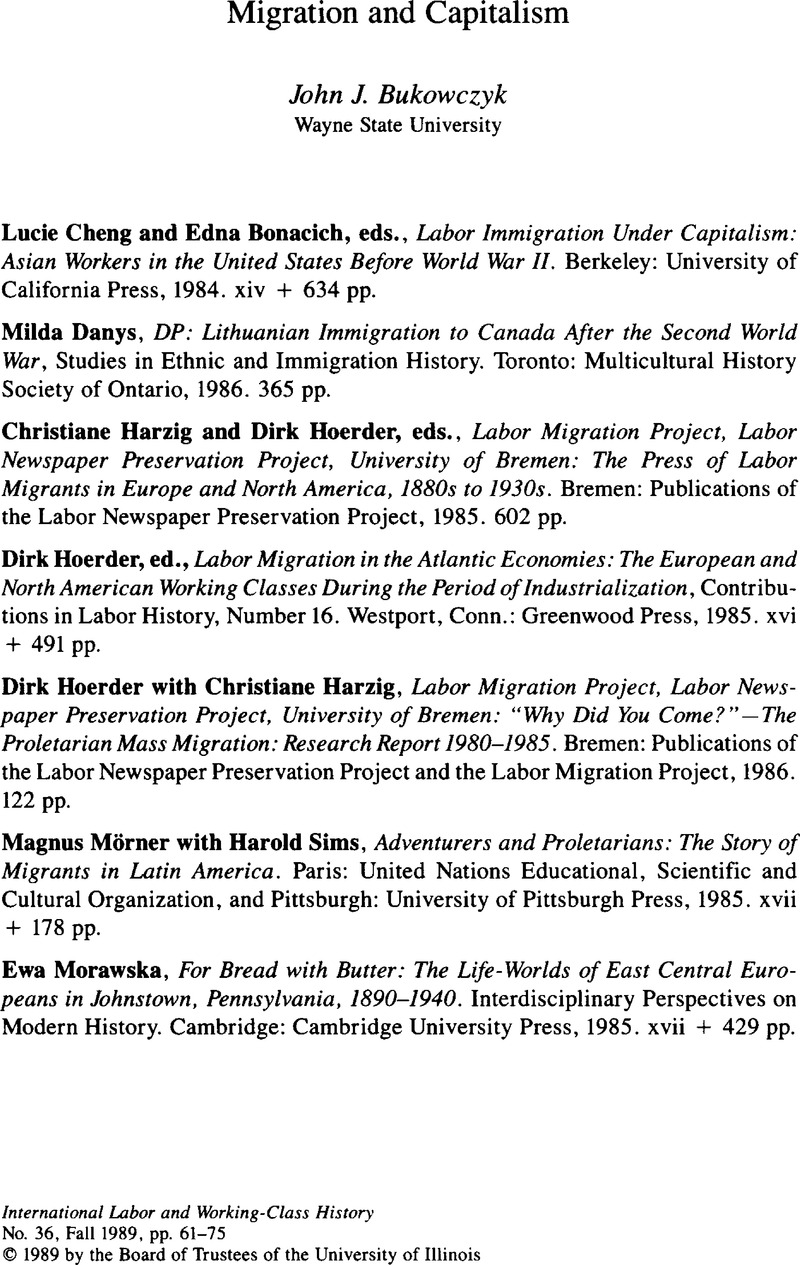

Migration and Capitalism

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 December 2008

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © International Labor and Working-Class History, Inc. 1989

References

NOTES

I would like to thank Nora Faires for her helpful comments on this essay. I would also like to thank the editors of ILWCH for their patience, kindness, and support during its preparation. These people, of course, are not responsible for the opinions expressed herein.

1. See Wittke, Carl, We Who Built America: The Saga of the Immigrant (New York, 1939)Google Scholar; Hansen, Marcus Lee, The Immigrant in American History (Cambridge, Mass., 1940)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Hansen, , The Atlantic Migration, 1607–1860 (Cambridge, Mass., 1940).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

2. Higham, John, Send These to Me: Immigrants in Urban America, rev. ed. (Baltimore, 1984)Google Scholar; Smith, Timothy L., “Religion and Ethnicity in America,” American Historical Review 83 (12 1978): 1155–85CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Handlin, Oscar, The Uprooted: The Epic Story of the Great Migrations That Made the American People (Boston, 1951).Google Scholar

3. See Higham, , Send These to Me, 76–77Google Scholar; Kennedy, John F., A Nation of Immigrants, rev. ed. (New York, 1964Google Scholar; originally published in 1958); and Fast, Howard, The Immigrants (Boston, 1977).Google Scholar

4. For the most developed argument that immigrants were “pulled” here, see Kuznets, Simon and Rubin, Ernest, Immigration and the Foreign Born, Occasional Paper 46 (New York, 1954).Google Scholar

5. Thomas, Brinley, Migration and Economic Growth (Cambridge, Eng., 1954)Google Scholar; and Thomas, , Migration and Urban Development (London, 1972).Google Scholar

6. See Thistlethwaite, Frank, “Migration from Europe Overseas in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries,” in Rapports, Comité International des Sciences Historiques, XIe Congrès International des Sciences Historiques vol. 5 (Stockholm, 1960), 32–60.Google Scholar

7. Certainly Marxist, “radical,” and quantitative social historians should not be lumped indistinguishably together. In the past fifteen years, however, I believe that American immigration and ethnic historians have drawn upon them rather eclectically and, in large measure, uncritically.

8. See Bodnar, John, The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America (Bloomington, Ind., 1985).Google Scholar

9. Thernstrom, Stephan, Poverty and Progress: Social Mobility in a Nineteenth-Century City, rev. ed. (New York, 1969)Google Scholar; Montgomery, David, Workers Control in America: Studies in the History of Work, Technology, and Labor Struggles (New York, 1979)Google Scholar; Gutman, Herbert G., “Work, Culture, and Society in Industrializing America, 1815–1919,” American Historical Review 78 (06 1973): 531–88CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Vecoli, Rudolph J., “Contadini in Chicago: A Critique of The Uprooted,” Journal of American History 51 (12 1964): 404–17.CrossRefGoogle Scholar For critiques of The Transplanted, see Social Science History 12 (Fall 1988).Google Scholar

10. See Handlin, , The Uprooted.Google Scholar

11. Thompson, E. P., The Making of the English Working Class (New York, 1963), 9.Google Scholar

12. For a longer review of Morawska, see Bukowczyk, John J., “For Bread with Butter: Life-Worlds of East Central Europeans in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, 1890–1940,” Labor History 28 (Winter 1987): 106–108.Google Scholar

13. See Piore, Michael J., Birds of Passage: Migrant Labor and Industrial Societies (Cambridge, Mass., 1979).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

14. See Herskovits, Melville J., The Myth of the Negro Past (Boston, 1941).Google Scholar

15. See Morawska, Ewa, “East European Labourers in an American Mill Town, 1890–1940: The Deferential-Proletarian-Privatized Workers?” in Sociology 19 (08 1985): 364–83.CrossRefGoogle Scholar Also see Bukowczyk, John J., “Polish Rural Culture and Immigrant Working Class Formation, 1880–1914,” in Polish American Studies 41 (Autumn 1984): 23–44.Google Scholar

16. See Oestreicher, Richard J., Solidarity and Fragmentation: Working People and Class Consciousness in Detroit, 1875–1900 (Urbana, 1986)Google Scholar; and Zunz, Olivier, The Changing Face of Inequality: Urbanization, Industrial Development, and Immigrants in Detroit, 1880–1920 (Chicago, 1982).Google Scholar

17. Morawska also interestingly notes that the urbanization of the immigrants was accompanied by the “ruralization” of the cities in which they settled (37). This theme deserves further attention.

18. In this argument, Mörner joins the late Argentine sociologist Gino Germani, cited in Morse, Richard M., “Trends and Issues in Latin American Urban Research, 1965–1970,” Latin American Research Review 6, 1 (1971): 14.Google Scholar

19. See Wallerstein, Immanuel, The Modern World System I: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century (New York, 1974)Google Scholar; and Wallerstein, , “Class-Formation in the Capitalist World-Economy,” Politics and Society 5, 3 (1975): 367–75.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

20. Fitch, John A., “The Explosion in Bayonne,” The Survey (21 10 1916): 62Google Scholar, quoted in Bukowczyk, John J., “The Transformation of Working-Class Ethnicity: Corporate Control, Americanization, and the Polish Immigrant Middle Class in Bayonne, New Jersey, 1915–1925,” Labor History 25 (Winter 1984): 69.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

21. Takaki's, Ronald otherwise excellent and provocative book, Iron Cages: Race and Culture in Nineteenth-Century America (Seattle, 1979), might have benefitted from a critical discussion of the not-yet-white immigrants.Google Scholar

22. Bail, Thomas, “Topicalization and Collective Experience: On the Use of Folk Song as a Historical Source,” in Labor Migration Project, Labor Newspaper Preservation Project, University of Bremen: The Press of Labor Migrants in Europe and North America, 1880s to 1930s, ed. Harzig, Christiane and Hoerder, Dirk (Bremen, 1985), 82.Google Scholar

- 1

- Cited by