Introduction

In 1983, the arrest of Noureddin Kianouri, the first secretary of the Tudeh Party of Iran came as a shock to the international community. In a letter of condemnation, communist parties from Indonesia to Jamaica pledged solidarity with their Iranian comrades.Footnote 2 The optimism initially brought by the 1979 revolution was severely reversed and the suppression of the Iranian Left by the Islamic government was regarded as an attack on the international Left. A significant voice of opposition came from Britain, with the Communist party of Great Britain (CPGB), the British Labor party, the trade unions and solidarity groups coming out in full support of the Tudeh and to take on the cause of Iran as their own. Although interest had existed since the 1940s, it was the 1979 revolution that firmly placed the Tudeh within the discourse of the British Left,Footnote 3 energizing the movement and solidifying its internationalist credentials.Footnote 4 Similarly, for the Tudeh, which had become side-lined in Iranian politics and had lost members to more radical strands of the Iranian Left, the attention it received helped renew its activism and sense of purpose.

From political parties to pundits, everyone had something to say about the events of 1979. While many were divided over support for Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the fate of the Tudeh and the wider Iranian Left throughout the 1980s became an important rallying point of solidarity, support, and protest. The presence of such transnational activism was clearly a response to the rise of conservative politics in the 1980s, heralded by the elections of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, a paradox that was pointed out by Stephanie Cronin in their presentation of the “Red 1970s.”Footnote 5 Spanning the years 1979 to 1991, the 1980s have long been used by many historians to frame the long-drawn out end of the Cold War.Footnote 6 This article applies this scope of time and space to capture the Tudeh's positioning within British Left discourse during a period of great change, while revealing the internationalist spirit that existed and of their interest in the wider world. Studies of the Tudeh abroad have mainly focused on either the Soviet Union or East Germany.Footnote 7 Knowledge about members’ exile to other European countries such as Britain, France, and Italy remain limited, while how communist parties in those countries viewed the Tudeh is still vaguely understood. Furthermore, understanding of the CPGB and the wider Left have mainly focused on the domestic experience or on its campaigns against fascism.Footnote 8 Scholars such as John Callaghan have alluded to the movement's international links but have largely ignored the links with Third World political parties. This paper attempts to fill this gap by examining the Tudeh in Britain during the long 1980s, pitting this experience against an era of great change for the Left, which encompassed the 1979 revolution, the Thatcher government, and the end of the Cold War.

This paper begins by looking at the brief history of the party from its foundation to its suppression and exile in the 1950s. This will be followed by an examination of British public interest in the party before 1979, followed by a close study of the British Left's interest in the party and the Tudeh's experience in Britain throughout the 1980s, which included interactions with the Labor party, the CPGB, trade unions, and other solidarity organizations. Party activities in Britain will be contextualized against what was happening in Britain and Iran at the time. It will be demonstrated here that the Tudeh featured prominently in British Left discourse, mainly due to the closeness felt to the party's struggles in Iran. The Left in Britain was not a homogenous group, and while many opposed the Tudeh's initial alignment with the Islamists during the revolution, a cross-party support base emerged for the party, Iran, and its workers when they faced suppression. This paper will present material sourced from the People's History Museum in Manchester, the British National Archives, as well as the archives of the University of Manchester, the School of Oriental and African Studies, the University of London, and from interviews with members of the Tudeh in Britain. For the first time, this varied collection of Tudeh pamphlets and newspapers, and British Left publications and correspondence will be examined closely and contextualized, providing a snapshot of British Left internationalism in action.Footnote 9 Taking a line from Eskandar Sadeghi-Boroujerdi in their study of the Organization of Communist Unity, the way the Tudeh was treated reflected how the British Left related to domestic and international developments.Footnote 10 This article will thus show that interest in the Tudeh and Iran was tied with local issues, which meant that support for the Iranian Left was tinged by the opposing discourses of the British Left and were subject to their indigenous causes.

The Tudeh Party's Early Entanglements with Britain

The Tudeh party was founded at the start of the British–Soviet military occupation of Iran in September 1941.Footnote 11 The abdication of the autocratic Pahlavi monarch Reza Shah a few weeks before birthed an era of political freedom and expression in Iran.Footnote 12 Many political prisoners were released, including the members of the Group of Fifty-three, a Marxist network that had been imprisoned since 1937.Footnote 13 After forming the party, they quickly established presence in Tehran, the industrial city of Isfahan, and in the oil-rich province of Khuzistan. Their initial programs that called for the rule of law and support of the constitution gained a cross-section of support, from workers to professionals, intellectuals to politicians.Footnote 14 The party's early success in the country also benefitted from the broad international alliance between democratic and communist forces against fascism, which saw Allied forces cooperating with communist resistance in France, Greece, Yugoslavia, and Malaya. Tudeh alignment with the Soviet Union during the war was therefore initially tolerated by the occupying British forces in Iran. But toward the end of the war, tensions between the two major superpowers bubbled into an open confrontation, which first materialized in the northern province of Iran when the Soviets supported an autonomous government in Azerbaijan.Footnote 15 It was during this crisis that the British public were first introduced to the Tudeh, where they were described in newspapers as Soviet supporters.Footnote 16 However, it was the party's activities around Iranian workers that sparked a deeper interest. In 1946, the Tudeh led several strikes among the oil workers of the Anglo–Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) refinery in Abadan, galvanizing not only company laborers but also those in other countries.Footnote 17 The British newspaper the Sphere carried a piece on the Tudeh's activities in the south, accompanied by an illustration of Tudeh emissaries arriving on the shore near Abadan. Most likely drawn from imagination, the artist relied on orientalist tropes, depicting them in turbans and traditional clothes, rowing canoes.Footnote 18 Reminiscent of the paintings of orientalist artists such as David Roberts, such romantic images and descriptions fed the British imagination but also helped visualize the party at the heart of Iran's labor affairs. The image of a local group standing up against an international oil company was inspiring and captured the postwar spirit of labor activism and the emerging wave of decolonization. While never formally colonized, Iran was still subject to British imperial ambition, which centered on its control of the oil.Footnote 19 As Steven Galpern pointed out, the AIOC “was a gateway to British informal control in the country, exercising overwhelming authority over daily life in the south [of Iran].”Footnote 20 The party called for nationalization from early on with key spokespeople making impassioned speeches against British control over Iranian oil.Footnote 21 The strikes ended with improved working conditions and saw an increase in British public interest in the Tudeh. Spearheaded by Ernest Bevin, foreign secretary in Clement Attlee's government and former minister of labor during the war, the British government took a keen interest in Iran's industrial affairs. The Tudeh's stand against British control of the oil captured the imagination of many, including the trade unionists in the Attlee cabinet. Bevin tried to find similarities in outlook with the Labor party, persuading his cabinet colleagues to familiarize themselves with the Tudeh program.Footnote 22 At the height of his enthusiasm, Bevin agreed to implement the demands of the party to improve the working and living conditions of oil workers.Footnote 23

It was during this period that British communists first took a serious interest in Iranian affairs. Iranian labor issues were already present in left-wing publications, including the monthly magazine of International Labor, Labor Monthly, whose editor was Rajani Palme Dutt, the one-time General Secretary of the CPGB and one of its most prominent idealogues.Footnote 24 Dutt earmarked Iran as a key cause against British imperialism, equating the control over Iranian oil as colonial subjugation.Footnote 25 The Tudeh's anti-imperialist views were made known when party leader Iraj Eskanderi's opinions were published in a British newspaper: “…we believe that, although the British Government may be progressive at home, it is still Imperialist abroad, and that it is supporting all these elements in Persia which we regard as reactionary.”Footnote 26 This aligned with the CPGB's own stand against empire and support for the independence of British colonies in Asia and Africa, which were later enshrined in its 1951 program, the British Road to socialism.Footnote 27 These links proved to be essential in laying the foundations for British Left interest in the Tudeh during the long 1980s, and explains the approach taken by the activities of anti-imperialist and anti-colonialism organizations such as Liberation and Unity Movement of South Africa (UMSA).

Like many other left-wing parties at the end of the war, the CPGB had gained widespread respectability from its participation in the war and its support of the coalition wartime government.Footnote 28 In 1945, party leaders Henry Pollitt and Dutt, now in their fifties, turned away from their earlier goal of violent revolution for Britain, working instead with the Labor party to improve the life of the British working class.Footnote 29 The CPGB's shift away from revolutionary politics saw Trotskyists in Britain emerge as the radical arm of the Left. They formed several internationalist socialist organizations, in opposition to the orthodox CPGB and what they considered to be Soviet-aligned politics. Indeed, as CPGB General Secretary Pollitt became identified more closely with Moscow, relations with other British socialists and left-wing entities suffered.Footnote 30 The Tudeh experienced a similar fate after the party leadership prioritized closeness to Moscow. Khalil Maleki, a key party leader, left to form the Third Force in response, fracturing the Iranian Left.Footnote 31 Throughout the 1960s, many young members became disillusioned by the party's political inertia brought on by subservience to the Soviets. Splinter organizations were formed such as the Revolutionary Organization of the Tudeh party of Iran, which looked to China, Cuba, and Vietnam for inspiration.Footnote 32 Others joined armed resistance groups, including the Marxist Fadai'an-e Khalq guerrillas.Footnote 33 Intellectually, Afshin Matin-Asgari regarded this period as one which saw the proliferation of strands of Iranian Marxism that was independent, even hostile, to the Tudeh and the Soviet Union.Footnote 34 These splits weakened the standing of both the main communist parties of Britain and Iran, while the difference of opinions between the British Left would influence how the Tudeh was treated and depicted—either as pro–Soviet, reactionary, or a cause to support.

After the Tudeh was implicated in an attempt on the life of Iranian monarch Muhammad Reza Shah in 1949, it was made illegal, and the party was forced underground. Many party leaders fled abroad including, Eskanderi, Abd-al Samad Kambaksh, and Reza Rusta, who found refuge in the Soviet Union and East Germany.Footnote 35 The breakdown in leadership in the country and the crackdown deeply traumatized the party. After Prime Minister Mohammad Musaddiq declared Iran's independence from the AIOC by nationalizing the oil, the party did not receive any substantial recognition nor were they allowed political participation, despite its experience in the south.Footnote 36 The coup that overthrew Musaddiq was driven by concerns that the Tudeh would seize power, and thus become a conduit of Soviet presence in the region.Footnote 37 Led by Conservative Prime Minister Winston Churchill, British dailies portrayed the party in such terms, fitting into prevalent Cold War rhetoric.Footnote 38 Although the likelihood of a Tudeh takeover was slim, it was enough to drive the United States and Britain to overthrow Musaddiq and replace him with the shah's choice, General Fazlollah Zahedi.Footnote 39 Maziar Behrooz regards the coup as a blow the party would never fully recover from and indeed, the post-coup era saw the Tudeh retreat further into isolation.Footnote 40 Kianori, and his wife, Maryam Firuz fled, joining those already in exile to form a central committee in eastern Europe. In Iran, many civilian members and sympathizers were also arrested, and numerous were executed.Footnote 41

In exile, the party found relative sanctuary, but not without setbacks. The party suffered from further splits. Those who were unhappy with the party's continued servility to Moscow in the aftermath of the Sino–Soviet split left to form the Tofan Marxist–Leninist Organization. While it was unable to restore lost support,Footnote 42 the party survived the turbulence and realigned more with the international Left.Footnote 43 Although active in European cities such as Vienna, East Berlin, Budapest, and Moscow,Footnote 44 the party's presence in Britain was relatively small.Footnote 45 Before 1979, the party did not have the same footing and presence it would have after. It was only with the revolution that they became more organized and active, basing themselves in southwest London as the Sazman-e Hizb-e Tudeh-e Iran-e dar Britaniya (Organization of the Tudeh Party of Iran in Britain).Footnote 46 Although initially an outlier and a sub-branch of the main Tudeh, which was based in East Germany, the party attempted to reach a British audience through their English-language weekly bulletin, Tudeh News.Footnote 47

Until the late 1970s, the party was largely absent from the radar of the CPGB, which seems hardly surprising, seeing the state of decline the party found itself in. Having lost much of the popular support it enjoyed after the war and unlike some of their European comrades, it remained a subtle force that never gained mainstream popularity, due to its desire to be aligned with the Labor party and its apparent subservience to Moscow. The party's reputation suffered, and its numbers declined significantly in the 1950s, particularly when it found itself unable to reconcile with neither Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev's anti-Stalin speech nor with the Soviet Union's brutal repression of the Hungarian uprising. Members such as John Saville and EP Thompson left to form a more autonomous Marxist group, which centered on the journal the New Reasoner, which later evolved into the New Left Review.Footnote 48 Throughout the 1960s, the Left in Britain continued to fragment, with trade unions staying away from the CPGB and forging their own independent paths.Footnote 49 With the 1979 revolution, the struggles of Iran were imposed onto this fragmented landscape, resulting in the polarization of opinions and attitudes toward the Tudeh.

The Tudeh, the Iranian Revolution, and the British Left During the Long 1980s

The momentum of the 1970s was undoubtedly electrifying, spanning the end of the Vietnam War, the oil crisis, the impeachment of US president Nixon, and the rise of popular protest, which reached a crescendo with the 1979 revolution.Footnote 50 Popular opposition to the shah had been steadily growing. In January 1961, the Confederation of Iranian Students held its first congress in the student union of the University of London, with delegates from Germany, Austria, France, and Switzerland.Footnote 51 The time seemed ripe for change and for international struggle. The rise of the new Left in Britain throughout the 1960s saw the evolution of discourse to include new conceptual tools to link local campaigns to foreign causes.Footnote 52 This era saw the proliferation of organic social movements, focused on human rights, students, women's liberation, workers’ rights, Black rights, and trade unions.Footnote 53 This burst of energy and activities led to the formation of transnational campaigning groups, birthing a new wave of socialist activismFootnote 54 and solidarity platforming, which would become a key driving force of struggle and demonstration.Footnote 55 British Left involvement in these trends laid the foundations for interest in Iran and solidarity for their Iranian comrades.

The Tudeh's role in the revolutionary period however was not without controversy. Party leader Kianouri called for the shah's overthrow, and openly sided with the Islamist opposition under the leadership of Khomeini.Footnote 56 This led to significant tensions within the party and with other organizations. Party veteran Eskanderi wanted to pursue a different approach for the Tudeh,Footnote 57 preferring an alliance with the National Front and Ayatollah Kazem Shariatmadari, who did not favor political participation of the clerics.Footnote 58 It was understood by the party and by their East German and Soviet patrons that the support for Khomeini would be temporary, predicting that the left-wing factions of the opposition would eventually overtake the religious elements to establish a workers and peasants-led government.Footnote 59 So convinced were they of this that the Tudeh went on to undermine the liberal governments of Mehdi Bazargan and Abolhassan Banisadr and pave the way for Khomeini.Footnote 60 The differences of approach between Kianouri and Eskanderi became a source of tension, and saw many members leave, including Manoucher Sabetian, a UK-based party member who had been involved in Tudeh activities in Britain.Footnote 61

In Britain, the alignment with the Islamic faction was a cause of heated debated between socialists and communists.Footnote 62 The British Trotskyist organization the Workers Group emphasized the political leverage of workers in the revolution but forewarned that the shah's regime could easily be replaced by an Islamic dictatorship, predicting that Khomeini would “isolate, disarm, and then crush the Left forces—the Fada'ian, the Tudeh and the factory and strike committees and to force the workers back under old conditions.”Footnote 63 But there were those in Britain, such as Liberation's General Secretary David “Tony” Gilbert who supported the Tudeh's decision. Described as an “old Stalinist,” Gilbert represented the orthodox communist party view of backing Moscow-aligned Tudeh out of the habit rather than due to any genuine conviction in the support for the Islamists. As David Greason explains, the Tudeh justified its alliance with Khomeini as part of the Soviet theory of pursuing a non-capitalist road to socialism. Many in the orthodox Western Left agreed with this model, arguing that it promoted self-determination and economic independence.Footnote 64 British Trotskyists used the unfolding events in Iran as a stand against others who they considered Stalinist. Here the anti-imperialist struggle of the Iranian revolution was directed against the more mainstream parties of the Left, such as the CPGB and the Tudeh. The British Socialist Workers party had a more nuanced interpretation of Leninism with regards to Iran, focusing less on the religious aspect and instead concentrated on the independence of the working class and their Iranian counterparts.Footnote 65 Such differences reflected the deep schism within the British Left, with groups torn between vying for alignment with Moscow, wider membership to the Labor party, and trying to maintain independence.Footnote 66

As events in Iran became more heated, the British Left saw an opportunity to internationalize their own causes.Footnote 67 In a pamphlet published by the International Marxist Group in December 1978, left-wing intellectual and writer for the New Left Review Tariq Ali expressed this: “For if internationalism is to be something more than words it must be concrete. Iran, in that sense, is also a test for us here in Britain and in all the imperialist countries. We should not fail it.”Footnote 68 These emerging ideas toward the revolution were in line with a growing move toward opposition to the shah. Over the years, British political outlets had become vocally critical of the Pahlavi monarch. In the British parliament, he received the strongest criticism from members of the left-wing faction of the Labor party, such as Stan Newens, as well as other trade unionists and left-leaning politicians.Footnote 69 Labor MP William Wilson was strongly critical of the shah, and later blamed his regime as the reason for the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in Iran.Footnote 70 Newens as chairperson of the Movement for Colonial Freedom, the precursor to Liberation, actively campaigned for detainees in Iran, directly appealing to the shah for clemency and justice while campaigning for support from other British politicians.Footnote 71

In the wake of the shah's departure in February 1979, the struggle for the political direction of the country began to play out. Khomeini returned from exile while the liberal politician Bazargan was declared prime minister. While Khomeini refrained from holding any official position, he quietly undermined Bazargan's government, and later, that of his successor Banisadr, by infiltrating the different arms of government and implementing his vision of Islamic rule, the vilayet-e faqih.Footnote 72 The Tudeh in Britain would later lament about the “betrayal of the leadership of the Islamic Republic of Iran.”Footnote 73 While such a sentence captured a genuine hurt, it failed to admit their deep miscalculation in their estimation of Khomeini and their complicity in supporting him. The Tudeh were not alone in their oversight. Many in Britain had underestimated Khomeini and downplayed the role of religion, focusing instead on the positive outcomes of the revolution. In his appraisal to the Middle East sub-committee of the Labor party's National Executive, Fred Halliday saw the revolution in secular terms and tried to see it as part of the progress toward socialism.Footnote 74

To further blur the support for Khomeini, 1979 came to symbolize a triumph of the workers and the breakdown of imperialist structures. The revolution made the cover of the winter issue of the Fourth International, the journal of the International Committee of the Fourth International, which included the Socialist Labor League and the Iranian Hezb-e Kargaran-e Sosialist (Socialist Workers party). They saw the revolution as a defeat of capitalism, and the “greatest upsurge of the world's oppressed since the October Revolution of 1917 itself.” The journal goes on to say that the “victories of the masses” were equally crushing to Stalinist principles of “Socialism in one country” and “peaceful coexistence” with imperialism.Footnote 75 The nature of the revolution touched other international movements. The African Peoples’ Democratic Union of Southern Africa (APDUSA), an organization affiliated with UMSA operating in Zambia and Britain, depicted the revolution as working-class-led, and a triumph of the oppressed.Footnote 76 The League for Socialist Action in Britain also emphasized the role of the masses, who they termed Khomeini's people, concentrating on the unity of workers, peasants, and students against the shah. Astutely, the league saw the lack of consensus over the direction of the revolution and emphasized that divisions could jeopardize the revolution.Footnote 77

The Workers Group focused on the “incalculable consequences for imperialism,” as a way to critique the British government, which despite the shah's unpopularity, had consistently defended him and continued arms sales to Iran.Footnote 78 For Ali, he outlined the goals of the revolution as: “the establishment of a republic, restoration of trade unions and political parties, free elections on the basis of universal adult franchise to elect a Constituent Assembly in order to draft a constitution, total nationalization of all the oil and multinational companies.”Footnote 79 As can be drawn from these interpretations, the revolution symbolized different victories for the different factions of the Left in Britain. They also suggest that many in the movement were aligned with an optimistic vision for Iran's future, albeit by downplaying Khomeini. What was clear from all the attention and debate was that Iran had become a focal point for British Left discourse.

In the immediate months following the revolution, the Tudeh tried to seize the opportunity to participate in the future of Iran. Party leaders, including Kianouri and Firuz, returned from exile. Declaring the toppling of the shah as a “heroic revolution,” the party depicted it as a triumph over imperialism, and as the ousting of US and Western European influence in the country.Footnote 80 Even when the country voted in a nation-wide referendum to establish the new government as an Islamic republic, the party regarded it as an important anti-imperialist stage of the revolution, further aligning itself by declaring:

The Tudeh Party of Iran, the proletarian party of the new type which has chosen Marxism-Leninism ideology as its guiding manual attempts to analyze in the light of this revolutionary and scientific ideology, the problems of the Iranian Revolution with its anti-imperialist and popular characteristics at its present stage, draw up its program on this basis and provide the toiling mases with this program.Footnote 81

Despite these attempts to engage, the party remained a minority political entity in the country. Nonetheless, the Tudeh tried to stay relevant by voicing support for the pro-Khomeini university students who stormed the US embassy in November 1979.Footnote 82 Their support led to an open break with Bazargan, whom they portrayed as an American puppet.Footnote 83 In the British press, the Tudeh's alignment with Khomeini was reported, while their support for the Iranian students holding the US embassy in Tehran hostage was depicted as a stand against America.Footnote 84 There were those in the British establishment who raised concerns about the party's role in the wider Cold War. Former Conservative minister Lord Cuthbert Alport cited the Tudeh's presence in Iran as a part of wider Soviet strategy to gain a foothold in the region, in light of the invasion of neighboring Afghanistan.Footnote 85 However, the party itself appeared lost in the chaos of the early 1980s, with many former and current leaders calling for different approaches to Khomeini.Footnote 86 The party's ambitions for power in revolutionary Iran was fraught by in-fighting over direction, a weak presence in the country, and its inability to forge a strong cross alliance with other parties.

The early 1980s was thus a period of struggle between the different forces that had brought about the shah's fall, reducing the revolution to a struggle between Islamic theocracy and liberal secularism. During these crucial months, while the governments of Bazargan and Banisadr were occupied with managing the international backlash of the hostage crisis, Khomeini and his followers continued to consolidate their power.Footnote 87 From this new position, he aggressively pursued his opposition, from rival religious leaders to parties of the Left. The Tudeh were complicit in this early suppression, accepting it as a necessary part of the revolution.Footnote 88 The party vowed to establish socialism in Iran and abroad, portraying itself as a champion of the workers, peasants, women, and youth, and as the main defender against reactionary circles.Footnote 89 This stand however stood at odds with its support for the Islamist regime, and their enthusiasm for Khomeini did nothing to protect them in the new Iran. In Britain, the party's role in the revolution had attracted both supporters and detractors. But as will be seen, their suppression was a turning point for the Left in Britain. Opposing groups came together in support of the Tudeh and other Iranian Marxist groups, with trade unions emerging as a key voice of support. This wave coming from 1980s Britain reflected both sympathy for the Iranian cause and their own indignancy and struggle in Thatcherite Britain.

The revolution had already highlighted similarities between the discourses of the Left and that of the Tudeh's struggle. In their newspapers, the party frequently engaged in topics of imperialism, and colonialism, embodied by US foreign policy.Footnote 90 Such rhetoric was echoed in the discussions of the British Left. International Marxist Group national secretary Brian Grogan in a pamphlet on Iran described the revolution as disruptive to the “projects of US imperialism.”Footnote 91 For many organizations, the toppling of the shah symbolized the end of tyranny, a triumph of the masses, and a victory against capitalism. The revolution and the Tudeh's role came to serve a specific purpose for each group, to suit their cause, reflective of the different stances within the Left in Britain. Support in Britain was initially limited due to the party's support for Khomeini, with many groups equating this support as a key factor behind the fall of the liberal governments of Bazargan and Banisadr and the rise of authoritarian theocracy. But when the fate of the Left in Iranian politics was reversed, the overall narrative shifted to one of suffering and betrayal. For the party, the support for Khomeini would haunt them for years and is a point of criticism from within and without.Footnote 92

By 1983, the suppression of the Left in Iran saw criticism disappear in favor of wide support for their Iranian comrades. Comfortable in power, the Islamic regime denounced Marxism as the ideological rival of Islam. The Tudeh was banned after it was accused of spying for the Soviet Union, which was followed by arrests of Kianouri and others as well as televised trials and party members publicly recanting Marxism.Footnote 93 This bitter battle between the Right and the Left resonated in Britain. Several solidarity campaigns emerged, forming an impressive bloc of support for the party and the Iranian Left in Western Europe.Footnote 94 Many organizations and charities stepped in to help Iranian students continue their studies, seek asylum, and remain in Britain. The National Union of Students worked together with Christian Aid to help students regardless of their political convictions, including explicitly, communists.Footnote 95 This shift to wide solidarity coincided with the landslide victory of Margaret Thatcher in 1983. Coming out of the Falklands War, the Conservative government felt confident enough to take on Britain's trade unions.Footnote 96 This found common cause with governmental suppression of workers and Left organizations in Iran.Footnote 97 The Tudeh in Britain steadily launched various campaigns that focused on the shared struggle for freedom and justice. The arrest of Kianouri and his wife led the CPGB to appeal directly to Khomeini. In a letter addressed to the supreme leader, the London district committee secretary somberly wrote: “We believe that this is a negative process by which the anti-Communist elements within the ruling circles in Iran are putting the lives of our comrades in serious danger and also the fate of the revolution.”Footnote 98 Although this letter may be taken as evidence of the CPGB taking the lead in the campaigns in Britain, the Tudeh actually found its support base among trade unions and other solidarity platforms.

The use of Iranian workers as an important symbol of resistance to the Islamic government was deliberate to resonate with the struggles of the British trade unions. Historically in Iran, the Tudeh had been active among workers and trade unions, as embodied by their control over the oil industry workers in the 1940s and their leadership of the trade unions in Iran. But due to their suppression and their exile abroad, they lost this support base. They became further alienated after their failure to establish meaningful traction among the labor force.Footnote 99 After the revolution the Tudeh attempted to revive their influence and campaigned for Iranian workers, particularly against the treatment of labor rights by the Islamic regime,Footnote 100 standing for better wages, improved benefits, and working conditions.Footnote 101 In the early 1980s, the party portrayed the revolution as a workers’ struggle,Footnote 102 and regarded Khomeini as anti-imperialist,Footnote 103 but with the suppression of the Left, they dropped their support for the ayatollah. Instead, the Tudeh tried to regain their influence among workers by establishing Bolshevik-inspired councils in opposition to their Islamic counterparts.Footnote 104 In the wake of the revolution, the Tudeh and the Islamic regime were locked in a struggle over labor and control of factories. M. Stella Morgana in their research visualized this conflict between Islam and communist ideology, which saw the successful appropriation of traditional workers’ symbols by the Islamic government. The opening of Islamic Associations in the workplace further undermined the control of the Tudeh and saw the supplanting of traditional trade unionism, which, coupled by strong suppression, defeated the Tudeh as a contender of power.Footnote 105

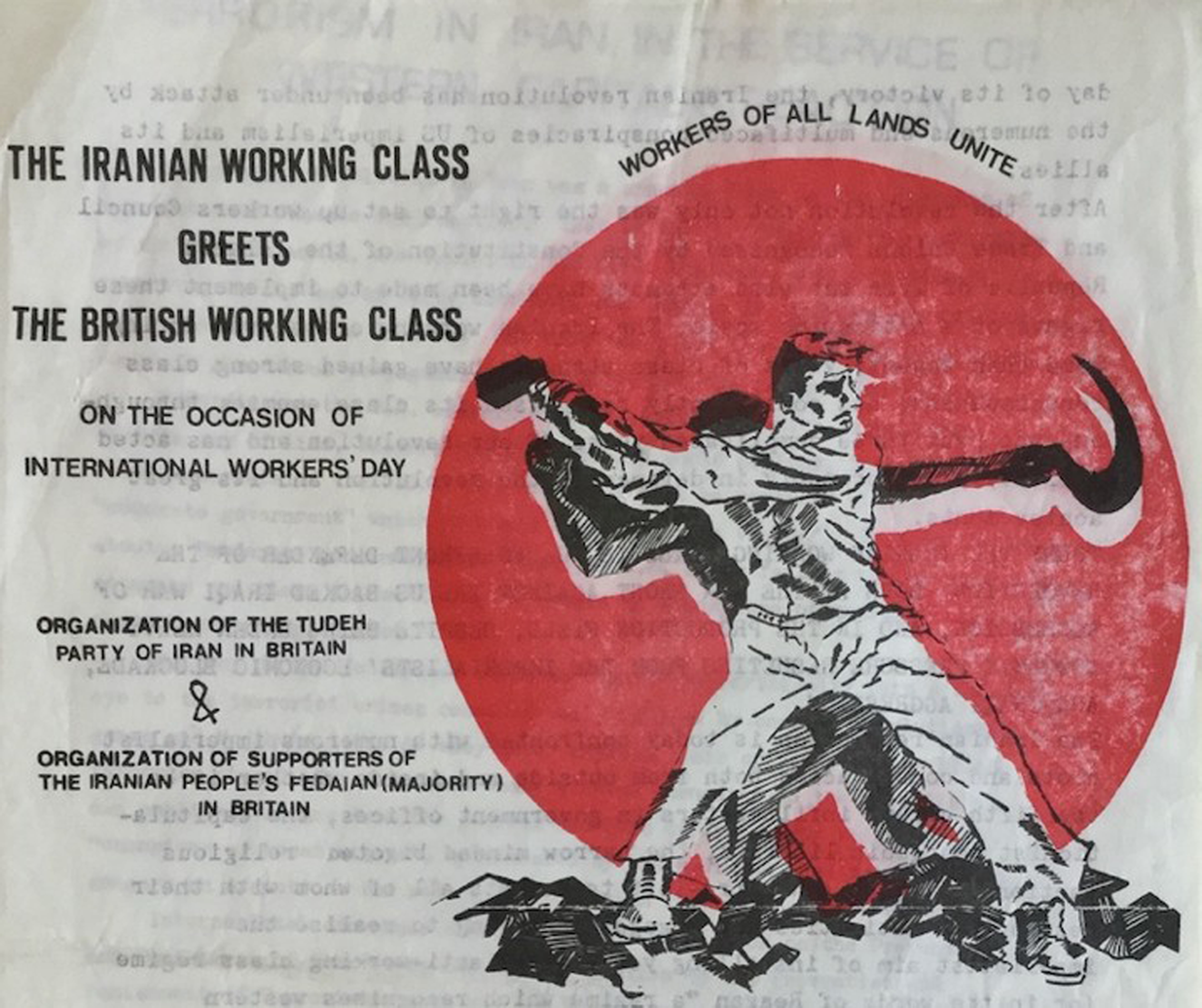

It is therefore no coincidence that throughout the 1980s, workers’ rights became the focus of the Tudeh's campaign in Britain. The outbreak of hostilities between Iran and Iraq became a key starting point for the Tudeh in Britain in this endeavor. The conflict was described as “imperialist” and was linked to the workers’ struggle.Footnote 106 From Britain, the Tudeh produced several pamphlets to highlight this cause, creating a connection with the struggle of British workers. One such publication was portrayed in a comradely fashion with the title: “The Iranian working class greets the British working class.”Footnote 107

Figure 1 A joint publication by the Tudeh party and the Fada'ian

These campaigns gained significant traction in Britain. The fight for social and economic justice in Iran, to a large extent, was the same one in Britain. The 1980s were characterized by Thatcher's conflict with the trade unions, and by the Conservative government's privatization of major industries. The miners’ strike of 1984–1985 revealed the struggle of British workers under an authoritarian state.Footnote 108 Arthur Scargill, president of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), became the public face of Thatcher's opposition, not only regarding the miners but also for ordinary workers. Union rights were suppressed, and unemployment was at an all-time high. Across society, many either lost their jobs or had little prospects of employment. Conservative fiscal policies, which favored city financiers, decreased the average worker's access to welfare and social benefits, leading to increased frustration and a turn to activism.Footnote 109 This shift was fueled by events beyond Britain. The Trotskyist Socialist Labor Group was inspired by the Polish Solidarity campaign, regarding it as an important example of workers’ leadership in determining its own affairs.Footnote 110 This internationalist approach further explains the prominent position of Iran within the discourse of the Left in Britain, however, with the defeat of the miners’ strike and the breakdown of trade unionism, campaigning involving the Tudeh, and support of Iranian workers disappeared.Footnote 111

The establishment of the Committee for the Defense of the Iranian Revolution (CODIR) in 1981 was another significant cornerstone for solidarity for Iran in Britain. Established by British labor and trade union activists in coordination with the Tudeh and other Iranians in exile in the United Kingdom, CODIR was instrumental in supporting the Iranian revolution's socialist cause.Footnote 112 However, in the early 1980s some within the Labor party condemned close association with CODIR due to its support for Khomeini, a notion most probably derived from the Tudeh's early acquiescence.Footnote 113 For the most part however, CODIR was able to draw many from the Left together in solidarity with Iran and the Tudeh. As seen in their flyer, the line “You fight for peace and social justice in Britain you should want the same for the Iranians” evoked a sense of shared responsibility over the events in Iran.Footnote 114 Other trade union organizations, including the Tobacco Workers Union, the National Union of Metal Sheet Workers and the Civil Service Union, were substantially involved, distributing publications by the Tudeh in Britain and lending support to public meetings. Having had many years of activism and participation in the activities of Liberation,Footnote 115 Jack Dunn of the Kent branch of the NUM chaired a CODIR meeting involving other trade unions on the role of Iranian workers in the revolution.Footnote 116

Figure 2 CODIR advertisement for a meeting regarding Iran

The high visibility of the NUM in the struggle for workers’ rights lent significant weight to the cause and to publicity on Iranian affairs. It also indicated the central position of the trade unions in solidarity campaigns. The CPGB was severely weakened by infighting and weak leadership, which caused an inertia that rendered them unable to keep up with the energy of the trade unions. Party leader Gordon McLennan was unable to make a definitive stand on international issues such as the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan or the Polish Solidarity campaign, which would have called for open opposition against Moscow.Footnote 117 While the 1980s saw limited activism from the CPGB, the Tudeh remained active and appeared alongside other sections of the British Left, able to gain organizational support from trade unions and other solidarity campaigns. CODIR emerged as a capable and visible organization that brought together other elements of the British Left with the Tudeh, successfully campaigning and holding solidarity events, including a week-long protest, with the support of British Labor parliamentarians, trade unionists, and academics.Footnote 118

The Tudeh's political campaigns were interjected by other social events. In 1980, the party held a gathering at the student union of the City University of London to celebrate the first anniversary of the revolution.Footnote 119 It also held yearly celebrations to commemorate the party's foundation. Invitations for the anniversary were distributed with promises of speeches, music, food, and campaigning.Footnote 120 These occasions were used to distribute pamphlets on the Tudeh's history and causes. At times, they also functioned as opportunities to re-write and represent the party's history and communist heritage. In a pamphlet on a brief history of the party, they presented themselves as successors of the older Iranian Communist party, even though in reality, this link was rather thin.Footnote 121 Interestingly, its publications were punctuated with Shi'a motifs as well as communist rhetoric, with workers being depicted as martyrs, which also tied in to Khomeini's own promotion of martyrdom in Iran's political discourse.Footnote 122 These attempts to keep relevant and hold on to its national and socialist heritage spoke of the party's deep connection to Iran and their attempts to use relevant motifs that could verbalize their ideological struggle.

The Iran–Iraq war was another key focus of Iran-related campaigning in Britain throughout the 1980s, with Liberation appearing at the forefront. The war had been a key policy concern for the British government. While it remained neutral in the conflict, it raised concerns regarding the war's impact on the geopolitical balance in the Persian Gulf and its effect on international shipping.Footnote 123 But for the Tudeh and the British Left, the war became another platform of solidarity for Iran. Led by a number of socialist politicians and activists including Lord Fenner Brockway, Newens and Gilbert, they came together with Iraqi and Iranian student organizations, the Fadai'an, and the Tudeh to speak out against the conflict.Footnote 124 Liberation's consistent campaigning gained support from a number of Labor MPs, including Diane Abbott and future party leader Jeremy Corbyn, as well as a number of trade unions.Footnote 125 The war was thus able to establish common ground with not only the Tudeh, but also brought a large cross-section of the Left in Britain together.

In February 1988, the Tudeh appealed to CPGB member Gerry Pocock to condemn the Islamic Republic and urged him to write to the United Nations Commission for Human Rights and the Iranian embassy in London on behalf of those imprisoned and appeal for their release.Footnote 126 Pocock persuaded his party to write to the Labor party to protest against the execution of Tudeh members in Iran.Footnote 127 These appeals and the focus on human rights violations in the Islamic Republic proved to be the last phase of the active campaign of the British Left and the Tudeh. Since the 1970s, the topic of human rights in Iran had become a key arm of Western foreign policy and a focus point for British Left activism. Since it was founded in London in 1961, Amnesty International had been at the forefront of lobbying for international human rights causes. As highlighted by Vittorio Felci, this paved the way for British left-wing discourse to become intertwined with global human rights at a transnational level, thus establishing Iran as a key cause, firstly under the shah then under the Islamic Republic.Footnote 128 In Britain, much of the campaigns from the 1970s were transferred into the next decade and were led by many of the same political figures. Liberation leaders Newens and Gilbert, who had been active in campaigning against the shah, spoke out against the human rights violations during the Iran–Iraq war.Footnote 129 In line with this trend, the Tudeh organization in Britain also produced a number of pamphlets and publications detailing the torture faced by the party in Iran.Footnote 130 Clearly effective, many in the British Left from trade unions to Labor MPs lent their support to CODIR, in solidarity with the Iranian people fighting against the repression of Khomeini's regime.Footnote 131

Since the revolution, the Tudeh drew support from outside the CPGB, able to align its cause and struggle with the wider British Left. This support was largely sustained throughout the long 1980s but were also subject to trends within the movement. For many, 1979 captured the feelings of the popular movement in Britain: a culmination of a decade of people power, the rise of the new Left on the one hand, and the fragmented nature of the orthodox Left on the other. The 1980s saw the different elements of the Left unite over Iran and form links with the Tudeh in exile in Britain. Criticisms over the party's initial support of Khomeini were put aside and solidarity campaigns for workers and against the war dominated the conversation. With the crackdown and suppression of the Tudeh in Iran, the party became a rallying point for several organizations and politicians in Britain: to serve as symbols of the difficulties of Thatcher's Britain and as a platform from which they could tap into international feelings of a shared struggle.

Conclusion

The fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union irreversibly changed the world the Tudeh was born into. Alongside people power campaigns and protests, the 1980s was an age of global challenge for communist parties and regimes who faced protest from those who had been neglected and side-lined.Footnote 132 Apart from a handful of countries, the end of the Cold War brought an end to communism as a political ideal.Footnote 133 In Britain, the CPGB had completely lost its political footing, and was fraught by internal disagreements. In 1990, the party was officially closed after seventy-one years.Footnote 134 Similarly, the late 1980s saw British trade unionism in decline with a loss of bargaining power and a reduction in membership.Footnote 135 This fatal combination of the global collapse of the Left and the breakdown of the Tudeh's solidarity platforms in the United Kingdom led to the end of the campaign for the Tudeh and Iran. Throughout the long 1980s, the party's general narrative of its career in Britain followed the notion that it would return triumphant, and that in the face of defeat and destruction, it will flourish.Footnote 136 This may have spoken of the party's long struggle, but in reality, interest in Iran was tethered to not only the causes of the British Left but to other global trends. Nonetheless, the Tudeh's experience in Britain during the crucial 1980s was an important example of a cross-party alliance of the broad Left.Footnote 137 The cause of Iran would only re-enter British public consciousness in a similar way with the Stop the War Coalition and with the campaign for British–Iranian journalist Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe.Footnote 138

The 1980s started as a decade of great change and ended in deep disappointment for the global Left. Looking back on this decade, Tudeh first secretary and Kianouri's successor Ali Khavari, described it as an era of ideological crisis.Footnote 139 Cynically, it could be said that the solidarity of the British Left for the Tudeh represented a lost moment for socialism: where the cries of protest remained marginal and had little impact in reality, hampered by the Tudeh's support of Khomeini, which blocked the party's path for genuine struggle. This article has shown that the Tudeh in Britain forged a relatively successful though brief campaign where they maintained a momentum in tandem with the different sections of the British Left. Although the revolution initially brought out opposing opinions on the party over its support of Khomeini, these were largely put aside to prioritize support for the Iranian Left and their struggles in Iran. The British Left and the Tudeh were thus able to create a transnational platform of hope and solidarity during a decade of chaos, instability, and struggle.