Sectarianism as both a practice and a discourse is a recurring discussion among scholars of the modern Middle East. To start with, it is necessary to clarify what we mean by sectarian or sectarianism, as misunderstandings may eventually freeze the scholarly debate. In the Lebanese context, the word al-ṭā’ifiyya, as Fanar Haddad argues, is generally used to refer to, and more often than not to condemn, the confessional political system characteristic of modern Lebanon. Specifically, historians have shown that the Lebanese representative and legal confessional system (al-niẓām al-ṭā’ifī), partly inherited from 19th-century Ottoman reforms and the creation of the mutaṣarrifiyya (the governorate of Mount Lebanon) and later confirmed by the French colonial mandate, does not legitimately or naturally reflect a supposed deeply rooted division based on sects within Lebanese society.Footnote 1

In his seminal work Fi al-Dawla al-Ta'ifiyya (On the Sectarian State), the Lebanese Marxist Mahdi ʿAmil argues that this sectarian system resulted from a relation of power maintained by modern colonial and political elites who defined and articulated divisions: “What if sectarianism . . . is not something, but rather a political relation defined by a specific historical form of the class struggle, conditioned by the Lebanese colonial structures?”Footnote 2 ʿAmil emphasized that because contingencies of sectarianism(s) are constantly reproduced, it is necessary to examine, not the sectarian phenomenon as an immemorial and fixed reality, but rather the context for its emergence. In line with this idea, Max Weiss proposes to distinguish between several expressions or layers of sectarianism. Based on the case of the Shiʿi community in the country, he identifies in particular two types of sectarianizing processes. One coming “from above” pertains to the strategy of divide and rule, controlled by the colonial administration and Lebanese political elite in the shape of national sectarianism: namely a series of allegedly homogenous sectarian units, politically distinct from each other, but all called Lebanese. The other comes “from below”; members of these communities reclaim sectarianism on their own terms, such as with demands for sectarian rights and political autonomy.Footnote 3 Major Lebanese sects and their relations to sectarianism have been examined through the critical lens of historians, but the Jewish community to this day remains understudied from the perspective of modern Lebanese history. In this article, I locate and discuss the dynamics of conflicts within the Jewish community in the aftermath of the creation of Greater Lebanon. I show how some Jewish actors made use from below of political opportunities provided by sectarianization from above to attempt to garner control over new Jewish political institutions in Lebanon. But by examining in particular activities in and around the Israelite Community Council in Sidon (CCS; al-Majlis al-Milli al-Isra'ili bi-Sayda), I show how and why these attempts to practice sectarianism were met with resistance.

To understand why some in the Jewish community expressed resistance to sectarianism, it is important to look at another critique of the sectarian paradigm developed by scholars of modern Lebanon. When the sectarian eye is applied too systematically to all kinds of historical phenomena, these scholars argue, other expressions of tensions or solidarities can be neglected. The category of sectarianism can be useful, insists Ussama Makdisi, but it is only one among many other ways to understand how individuals articulate sameness and otherness, differences and similarities. After all, belonging to one of the eighteen formally acknowledged religious groups in Lebanon does not account for all conflicts in the history of the country.Footnote 4 “Are sect and sectarianism meaningful analytical categories for the study of Lebanon?” asks Max Weiss. Differentiation is a subjective and multilayered process, Suad Joseph answers, and dynamics within Lebanese society should not be reduced to sect-specific mobilizations.Footnote 5 It is therefore necessary to explore other categories of analysis in which state and society construct differences and similarities, such as class or sex or, for the purpose of this article, one's relation to space.Footnote 6

In The Production of Space, French philosopher Henri Lefebvre examines how social relations, everyday practices, and territorial divisions conceived politically produce space.Footnote 7 Conception and perception of space can in turn affect the ways in which individuals living in the same space imagine and construct sameness, as well as how they articulate otherness with people living elsewhere, even when they belong to the same political, social, or religious group. In Lebanon, in addition to political divisions based on sects, authorities also produce and control spatial norms likely to affect social life in the country, such as territorial divisions into governorates (muḥāfaẓa), districts (qaḍā’), and municipalities (baladiyya). Also, narratives of tensions and solidarities in relation to regions, such as north versus south, city life versus country life, mountain against the sea, or one city versus another—like Sidon and Beirut in the case I address—show that identities in relation to space potentially emerge in various contexts and forms.Footnote 8 In what follows, I contend that, despite connections that tied Lebanon's Jews together administratively in one community subsequent to the political restructuring of the country that took place in 1920, tensions and conflicts emerged between Sidon and Beirut, pertaining to their relations to space.

Although historical sources on the Jewish community in Sidon are still scarce, the Fonds Youssef Melhem Politi du Conseil Communal Israélite de Saïda archive uncovered in 2013 contributes to a better understanding of major political events and developments there from the 1920s to the 1960s. The archive is composed mainly of Arabic handwritten meeting minutes (MoM) for the Israelite Community Council of Sidon (CCS) between 1919 and 1959. It was digitized, partly translated into French by Yolla Polity (daughter of Youssef Politi, president of the CCS between 1931 and 1979), and made available to various archival institutions. I will examine the Fonds Politi along with other contemporary sources, such as Arab historiography on the city of Sidon, Jewish newspapers, as well as Western philanthropic reports.Footnote 9

Sidon, the South, and Interreligious Interactions

Until the first half of the 19th century, the Ottoman eyalets of Sidon and Tripoli encompassed Syria's major port cities, including Sidon itself.Footnote 10 However, a number of factors led to the economic, political, and administrative growth of Beirut at the expense of Sidon, and by the end of Egyptian rule over Syria (1831–40), Sidon's commercial preeminence had started to fade. As a result of these transformations of the geopolitical scene, the city increasingly lost its previous influence and prestige in the region. It progressively transformed into a provincial city subordinate to Beirut, which later became the administrative capital of the province bearing its name (Vilayet Bayrut).Footnote 11 Although the rivalry between the two port cities of Beirut and Sidon never reached the level of that between Beirut and Damascus or Beirut and Tripoli, the capitalization of Beirut was received with bitterness among certain Saydawis.Footnote 12 As Cyrus Schayegh has shown, witnesses from within tended to tackle the issue of Sidon's decline, as it was being “crushed” by Beirut, with nostalgia and despair. This bitterness is most visible in the case of the scholar Ahmad ʿArif al-Zayn, whose work I will examine below, and it persisted in later historiography on the city of Sidon, as James Reilly has shown.Footnote 13 However, historical testimonies also focus on positive aspects. In a detailed study on the Ottoman province of Beirut published in 1917 by two Arab Ottoman officials, Muhammad Bahjat and Muhammad Rafiq al-Tamimi, entitled Wilayat Bayrut (Beirut Province), the authors—while depicting an overall negative impression of the city—also insist on Sidon's extreme beauty and the exceptional variety of plants, trees, flowers, and orchards. Strong and visible upper and middle classes existed among the various religious communities, and the recent establishment of new schools greatly contributed to the modernization of the city's structures. Generally, they found the people from Sidon to be hard workers; “there is no trace of laziness in Sidon,” the authors conclude.Footnote 14 The report also emphasizes interreligious proximities in Sidon. When they discuss Sidon's social customs (al-ʿādat al-ijtimāʿiyya) Bahjat and al-Tamimi insist that members of various sects (they describe Sunni, Shiʿi, Christian, and Jewish customs) were not isolated blocks and therefore did not have perceptibly separate habits. The officials even conclude from their visit to Sidon that tensions within religious communities in Sidon were generally much higher than among them, something they found to be “confusing.”Footnote 15

In fact, as part of the process that led to the formation of Greater Lebanon in 1920, the French mandate incorporated large parts of Jabal ʿAmil into what came to be known as South Lebanon. And although the South emerged in French administrative language as a predominantly Shiʿi region, historical studies have successfully debunked deep stigma around a supposed monolithic community. Scholars have shed particular light on the heterogeneous nature of its society from the perspective of class and sect, and on the importance of interreligious interactions in its various urban centers.Footnote 16 For instance, Toufoul Abou-Hodeib has examined the shared tradition of visiting shrines in various sites of Palestine and South Lebanon. She has shown how the repetitive nature of the ritual around the holy site of Maqam Sidun (literally “the abode of Sidon” in Arabic), or Nabi Saydun located south of Sidon where the prophet Zebulon, son of Jacob, is believed to be buried, and venerated by Muslims, Christians, and Jews alike contributed to shape the contours of a local interreligious urban identity around the city of Sidon.Footnote 17

Abou-Hodeib's argument of religious plurality in South Lebanon echoes the work of the Shiʿi scholar Ahmad ʿArif al-Zayn (1884–1960) on the city of Sidon. Because there was no historical research dedicated entirely to Sidon, al-Zayn decided to publish a compilation of articles he had originally published in al-ʿIrfan (literally “knowledge”), a journal he himself founded in 1909, which became an important tool for the promotion of knowledge, culture, and education in the region, under the title Tarikh Sayda (The History of Sidon) in 1913.Footnote 18 In both Tarikh Sayda and al-ʿIrfan, al-Zayn addressed on numerous occasions the importance of interactions between religions and sects in Sidon, particularly in relation to religious celebrations. When Christmas falls very close to the Mawlid al-Nabi (Birth of the Prophet Muhammad), he noted that both celebrations were attended by Christians and Muslims alike. Also, when Christian Easter and Jewish Passover were celebrated on the same day in April 1922, the celebrations were interreligious.Footnote 19

Following Lefebvre's notion of space production, shared practices, whether for interreligious or social purposes, could have in fact created special attachments to local spaces where these interactions had taken place and fostered local identity formation. With the concept of “ecumenical coexistence,” Ussama Makdisi, although not directly addressing the spatial dimension per se, also argues that these attachments accounted for people living in them. Sidon, because of both territorial exclusion and strong interreligious activities, perfectly illustrates the idea that a shared space can (although not always) “transcend sectarian difference.”Footnote 20

Jews in Modern Lebanon: Old and New Quarrels

Before digging into the multilayered processes of differentiation within the Jewish community in Lebanon, historical context of its presence in modern Lebanon and Syria is necessary.Footnote 21 The scholarly literature on the topic of Jewish circulations in the Mediterranean basin between Spain, Greece, Turkey, Palestine, Egypt, and the Maghrib shows that by the 19th century Ottoman cities of Syria had become major hosts for a wide range of Jewish populations. In addition to the preexisting Arabic-speaking Jewish populations, as well as earlier waves of Sephardi and Maghribi immigration, Ashkenazi Jews in great numbers settled in Syrian cities over the course of the century to escape anti-Semitic persecution in northern and eastern Europe. Hitler's later rise to power and the subsequent increase in German Jewish immigration became a major object of discussion in the Lebanese press. An announcement addressed to “Jews living abroad” (im Ausland lebende Juden) distributed in Beirut in 1939 by the German consulate to force Jews with German citizenship to take on additional names (Israel for men, Sara for women) to identify them, testifies to the significant presence of German Jews in the area.Footnote 22 The Ashkenazi immigration sometimes left local Jewish institutions in a state of crisis. School officials wrote urging requests for funding from abroad to help support newly arrived pupils.Footnote 23

After the creation of the State of Greater Lebanon in 1920, Jewish communities from Syria and Iraq also sought refuge in Lebanon, in waves. The most important immigration to Lebanon resulted from the 1925 Syrian revolt, which produced the temporary displacement of several hundreds of Jewish families from Damascus to Beirut, and from the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, notoriously making Lebanon “the only Arab country in which the number of Jews increased after the first Arab-Israeli war.”Footnote 24 This wave of Jewish refugees created a new state of crisis for Jewish school institutions in Lebanon. The director of the Alliance Israélite Universelle (AIU) school for girls in Beirut wrote to the headquarters in Paris asking for help. She had transformed her office into a classroom to host new pupils but room had nevertheless become scarce, she complained.Footnote 25 It is worth noting here that the Jewish community's modern history echoes in several ways the historical narrative of Lebanon as a pays de refuge (country of refuge) for various religious communities, such as Armenians, Palestinians, and Syrians.Footnote 26

The Jewish community was marked by strong ethnic, national, and linguistic diversity, which came with its lot of challenges. In The Jews of Beirut: The Rise of a Levantine Community, Tomer Levi discusses the difficulties pertaining to political representation within the Lebanese Jewish community in such a context. Article 2 of the community statutes of 1909 stipulated that “the numbers of members in the council will be twelve, six of whom are natives, and six who are not natives,” directly addressing the tensions between Ottoman and local Jews and foreign nationals. Levi also sheds light on a detailed report by the director of the Beirut branch of the AIU school between 1905 and 1909, Yomtov Semach. The teacher deplores the existence of ethnolinguistic divisions between “Arab Jews, Sephardic Jews, and Russian Jews.”Footnote 27 The distinction between the three groups, albeit approximate, appears in various European, Hebrew, and Arabic language sources, although at times under different names. Arab Jews (al-Yahūd al-ʿArab) is often synonymous with oriental Jews (sharqī in Arabic and mizrahi in Hebrew) and usually refers to the Arabic-speaking Jewish populations who settled in the region prior to Sephardis.Footnote 28 The latter originally came from Spain and some (but not all) kept using the Ladino language. Some historical sources used “Russian Jews” to refer to all Ashkenazi Jews who fled the pogroms in the late 19th century, even though some came from Germany and elsewhere. An additional distinctive group worth mentioning here because it is often included in the Sephardi category comprises the Romaniote, or Greek-speaking, Jews. Many kept a Greek name but not the language, like the Politi family discussed below, who spoke Arabic.Footnote 29

In the ever-growing field of “Mizrahi studies,” or studies on Middle Eastern Jewry, the phenomenon of modern identity formation has been at the center of scholarly attention. On the one hand, works based on rabbinical sources or from the perspective of Istanbul during the Tanzimat period have shown how modern Jewish identities were already shaped by the mid-19th-century millet administrations. On the other hand, from the perspective of intellectual history, studies based on printed material, often in Arabic, as well as European, colonial, and Zionist accounts, emphasized contributions of Jews in the Arab public sphere.Footnote 30 By exploring the complex and multilayered mechanisms of identity formation in Jewish communities, all these works have successfully relocated their histories within the field of Middle Eastern studies. With some notable exceptions however, very few studies have examined the impact of shared spaces on identity formation. Studies by Orit Bashkin and Dena Attar on Jews in northern Iraq emphasize the gap between Jewish experiences in Baghdad and those in Kirkuk, Mosul, and other places in the north. Similarly, Emily Gottreich Benichou examines the impact of shared spaces in the city of Marrakesh, in the history of Jewish-Muslim relations in Morocco.Footnote 31 Identities in these cases were not only imagined and shaped by religious connections, these scholars show, but also by local spaces they shared with other religious communities. In Lebanon, although Tomer Levi does not directly address the impact of space in the shaping of modern identities within the Jewish community, he nevertheless insists that the ethno-national diversity within the Jewish community was not the sole source of tension. He notes that Jews throughout the country were divided over “other quarrels,” namely tensions between communities located in different cities (mainly between Beirut, Sidon, and Tripoli), but without going into further details.Footnote 32

To understand the nature of these “other quarrels” it is worth digging more deeply here into the transformation in the status of Jews in the late and post-Ottoman period. Jews of the Ottoman Empire officially became a millet over the course of the 19th century in ways similar to the Armenians and Greeks. In 1835, the chief rabbi (hahambaşı) was appointed by the government in Istanbul and officially became both head and representative of all Jewish communities throughout the empire, with local hahambaşı offices in provinces, districts, and cities. The General Regulations of the Rabbinate (Hahamhane Nizamnamesi), the organic law for the Jewish millet promulgated in 1865, later confirmed the centralization of Ottoman Jewry characteristic of the Tanzimat era.Footnote 33 But the new rabbinical institution centralized in Istanbul was met with strong resistance in various provinces of the empire, and more often than not local authorities continued to exist parallel to authority imposed from Istanbul. In some cases, like Damascus, a new leadership pattern emerged, where two chief rabbis ruled at the same time. One was in charge of dealing with Ottoman authorities, whereas the other held a religious position.Footnote 34 With the creation of the State of Greater Lebanon in 1920, things changed once more for the Jews who found themselves in what became Lebanon. Given the confessional nature of the political system in the country, the transition from millet to citizen was admittedly far from being clear-cut juridically speaking, as with other sects. But in representative politics, major reconfigurations of authorities took place. Ottoman provinces and districts, as well as administrative structures that depended on them, no longer existed, and Jews in Lebanon, who numbered approximately 3,500 according to the census conducted in 1921, all became part of the Lebanese “Israelite sect” (al-ṭā’ifa al-Isrā’īliyya).Footnote 35 The authorities also recognized the Israelite Community Council (al-Majlis al-Milli al-Isra'ili) of Beirut created in the aftermath of the Young Turk revolution in 1908 as the central body within Lebanon. Although smaller communities in Sidon and Tripoli also had their own councils, these were consequently made subject to the authority of Beirut. And in 1922, the chief rabbi of Beirut became the chief rabbi for all Lebanon.Footnote 36 By doing this the authorities, while reusing an already existing system based on confessional representation, also contributed to shaping from above a new national sect, the “Israelite sect,” that did not exist as such previously, with new hierarchies, new control networks, and new spaces. Although political sectarianism per se was not entirely new, the scope and limits of national sectarianism were. The situation transformed into an opportunity from below for some to practice new forms of sectarianism and benefit from it.

The Jewish Community in Sidon: A Localized History

In Tarikh Sayda, Ahmad ʿArif al-Zayn estimated the total Jewish population in Sidon to be 250 in 1850, and 819 (for a total number of 13,184 individuals) in 1908. The two Ottoman officials and authors of Wilayat Bayrut, Bahjat and al-Tamimi, present similar numbers: in 1910, 888 Jews were living in the heart of Sidon. According to the Montefiore census, there were 150 Jewish families in Sidon in 1839 and 171 in 1866. Jewish children in Sidon attended one of two Talmud Torah or Jesuit or Protestant schools, until a branch of the Alliance Israélite Universelle opened in 1902 (accepting around 120 pupils the first year). It was later followed by Hebrew schools and kindergartens in 1920. Until 1855, Jews only had one synagogue, but a second one was erected in the early 1860s. Both buildings were located in the center of Sidon. The Jewish community also had financial charge of maintenance of the Maqam Sidun until at least the late 1950s, as evidence shows that Jews submitted requests for financial help in 1957, after an earthquake partially destroyed the site.Footnote 37

An account published in one of the first issues of the Jewish Arabic newspaper based in Beirut, al-ʿAlam al-Isra'ili (The Israelite World), in September 1921 gives a better sense of how the Jewish community in Sidon was represented or represented itself. Because al-ʿAlam al-Isra'ili, founded and edited by the journalist Salim Elyahu Mann, had the ambition of becoming the main organ for Arabic-speaking Jewish communities in Syria and Lebanon and even reaching readership in Palestine and Iraq, efforts were undertaken to cover current affairs in Sidon, although at times unsatisfactorily.Footnote 38 An anonymous author, presumably a member of the Jewish community in Sidon, wrote about the growing isolation of the city in the region. Despite the zeal of the age-old Jewish community members in Sidon who “are neither lazy nor bored,” and despite their numerous activities in local industry and commerce, their prosperity was in decay, the author argues. First, because of the departure en masse to Brazil and North America, the Jewish community had been progressively decreasing in number. In fact, important waves of Jewish transatlantic immigration from Sidon were observed at least until the 1930s, to the point that the Jewish community in Sidon was reportedly composed of only “old people and children.”Footnote 39 Some were encouraged to return after the French occupation, hoping that the acquisition of land would apply to them as it did for Jews in Palestine. But these hopes proved to be a great disappointment, he bitterly concludes: “Yes, some have returned from exile (al-mahjar) after the occupation but the law for the land . . . applied to the Zionists did not apply to the Jews in Sidon.” Second, they could not rely on external financial support, the author complains. Compared to other Jewish communities in the region such as Palestine that benefited from the support of external charitable associations, Sidon's Jews felt abandoned. A feeling of in-betweenness and isolation can be read between the lines; Beirut and Palestinian coastal cities seem to have somehow stolen Sidon's thunder by excluding it from regional influence, in the eyes of the anonymous author.Footnote 40

Post-Ottoman reshuffling of territorial entities affected the Jews in Sidon on several levels, some of which differed from effects on other sects in the region. Like other coastal populations around the cities of Tripoli and Beirut, Saydawi Jews had to cope with the redefinition of what it meant to be a national sect, as well as with the centralization of authorities in Beirut, as I have described. But they had to face an additional challenge, this time specific to their Jewishness, and pertaining to mobility to the south. Laura Zittrain Eisenberg and Guy Bracha have convincingly shown that prior to World War I the northern borders of Eretz Israel were not precisely defined in the imagination of early Zionists, which is why they initially explored various sites for future Jewish settlements in South Lebanon. Sidon's oil and soap factories, in particular, attracted the interest of Zionist entrepreneurs who established strong connections with Jews in Sidon.Footnote 41 To be sure, connections between Palestinian Jews and the Yishuv and Lebanese citizens and institutions continued well after the establishment of Greater Lebanon, as Caroline Kahlenberg has shown.Footnote 42 As a matter of fact, the question of southern borders was far from being settled after the declaration of Greater Lebanon.Footnote 43 However, free circulation was partly reduced after that, and, more importantly, hopes for fruitful investments in Sidon were suddenly dashed. Also, as connections between Jews in Palestine and in Lebanon were being reduced, they progressively became limited to Beirut, as this grievance from Sidon addressed to the editorial board of al-ʿAlam al-Isra'ili, testifies: “How nice it would be if you [Salim Efendi Elyahu] could take two hours maximum of your time on your way [from Beirut] to Palestine to study the affairs and situation of our little community [in Sidon].”Footnote 44 In other words, centralization of Lebanese power in Beirut in the north and isolation from the Palestinian Yishuv in the south weakened the activities and influence of Saydawi Jews in the region, which became increasingly localized.

Two external reports also document the conditions of Saydawi Jews living at the turn of the century. One was produced by the director of the Beirut branch of the Alliance Israélite Universelle, Meir Angel, in 1902, and the other was written on behalf of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) by Benzion ʿUzziel and Jack Mosseri in 1919.Footnote 45 The French and American reports emphasized in very alarming terms the misery of Sidon's population as a result of the city's decline, and the symptomatic replacement of luxuriant gardens, as well as of lemon and orange orchards, by dirt and dust. “Sidon, once the queen of the seas, is today nothing more than a dark and sad town of 15,000 to 18,000 souls . . . a big village with no commerce and industry,” stated Meir Angel from AIU. ʿUzziel and Mosseri estimated that “no ghetto in the world can be worse than that of Sidon.” As Tomer Levi points out, reporting on systematic misery, vulnerability, and backwardness of oriental Jewish communities was in fact necessary to justify activities and interventions from charitable foundations.

But more importantly, the fact that ʿUzziel and Mosseri insist on the total absence of any preexisting Jewish political structure in Sidon is of particular significance here: “no community organization whatever exists in the place.”Footnote 46 In fact, I contend that there was political incentive behind the authors’ choice to emphasize the incapacity of Sidon's Jewish community to rule itself appropriately and sustainably. All authors, whether Benzion ʿUzziel and Jack Mosseri reporting for JDC or Meir Angel for AIU, had strong connections and interests in Beirut. Whereas Angel's connection as director of the AIU branch in Beirut is obvious, ʿUzziel's and Mosseri's instrumental role needs further explanation. A few days after their first visit to Sidon, which took place in the context of a tour of Syria in 1919, on 15 February, the Israelite Community Council in Sidon was elected in the presence of Jack Mosseri himself, as well as that of two delegates representing ʿUzziel, who were themselves members of the community council in Beirut (M. Barzel and M. Darwish). And although Benzion ʿUzziel, as chief rabbi of Jaffa, had no direct authority in Beirut, he expressed his support for and solidarity with Beirut's Jewish authorities on several occasions.Footnote 47

The newly elected CCS was composed of five members: Ishaq Diwan (treasurer), Ibrahim Barzilay (secretary), Musa Braun, Yusuf Nigri, and Ibrahim Khayyat. Some of them, like Nigri and Khayyat, known to be the most famous treasurers (ṣarrāf) working for Istanbul, were already active before the change of regime.Footnote 48 Although this shows some form of continuity with previous political practices, major reconfigurations of power also took place. In particular, the committee in Sidon was intentionally elected without a president, “so that it may act under orders from Beirut.”Footnote 49 From then on, the CCS was supposed to act and take all decisions with the approbation of Beirut, which would as well represent its interests. The absence of a CCS president, which later became an object of contention, gave members of the community council in Beirut who were involved in the creation of the CCS opportunities to exert political as well as financial control over Sidon. In other words, they used political tools provided by national sectarianism, namely the supposed political homogeneity of the Lebanese Israelite sect centralized in Beirut, to subject the CCS to their authority. However, the way state and communal authorities imposed and practiced national sectarianism soon produced resistance and hostility among some in the Saydawi Jewish community, whose voices I will examine in the next two sections.

Musa Braun and Ibrahim Maʿtuq Nigri: Sidon's Voices of Dissent

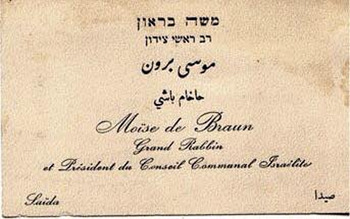

Two prominent members of Sidon's Jewish community in particular, Musa Braun and Ibrahim Maʿtuq Nigri, embodied dissent against the capital authority in Beirut, from the point of view of representative politics and finance. Paradoxically, although the report submitted to the JDC by Jack Mosseri and Benzion ʿUzziel deplored the absence of a communal structure for Sidon, it also provided evidence for such a structure: “A Hotel keeper by the name of Braun calls himself Chief Rabbi and President of a Va'ad composed of so called representative heads of families.”Footnote 50 Soon enough, by claiming the title of chief rabbi in Sidon in opposition to the centralization of the Chief Rabbinate of the Lebanese Republic in Beirut, the widowed innkeeper of Galician origins Musa (Moshe) Braun became the CCS's bête noire.Footnote 51

On 15 February 1919, Braun, who previously worked for the Singer Corporation, manufacturer of sewing machines, joined the CCS as one of its five founding members. He was consequently assigned a few tasks, such as listing the names of the poor to be sent to a charitable association in Rio de Janeiro. But things quickly started to turn sour. Members of the CCS soon complained about Braun missing meetings and not completing his tasks. One major object of contention was control over the stamp of the Lebanese chief rabbinate. The stamp gave authority to validate religious ceremonies and contracts in the name of the chief rabbinate, in exchange for money. Repeatedly between 1919 and the late 1940s, Musa Braun used the stamp without the council's consent, even after its members took the decision to replace it to avoid usurpations. As soon as April 1919, the CCS addressed a personal request to Musa Braun to return the stamps he was using, followed in 1920 by a warning, insisting that he had no permission to proclaim himself chief rabbi (ḥākhāmbāshī). According to the council's investigation, Braun was living with a girlfriend (ṣāḥiba) “contrary to religious rule” and could therefore not claim the title of rabbi, least of all chief rabbi. When in 1922 Sulayman (Shlomo) Tagger officially became chief rabbi of Lebanon, he published an official announcement that there was no other chief rabbi in the country.Footnote 52 More than a decade later, in May 1933, as members of the CCS still complained that Braun was using the title of chief rabbi despite multiple warnings, regional authorities intervened. The governor of South Lebanon Kamil (Camille) Shidyaq sent a formal request using similar warnings addressed to Braun.Footnote 53 Two important documents, one decree by the high commissioner on 7 January 1933, and one by Asʿad ʿAql, the public prosecutor of South Lebanon, on 1 March 1933, also communicated that “there was only one Israelite community in the Republic of Lebanon and therefore one chief rabbi.” At this point, Musa Braun reacted officially for the first time, by answering that he had lost the stamp years ago. However, new evidence showed that he continued behaving as the legitimate chief rabbi of his community in Sidon (Fig. 1). On 1 April 1939, when Braun came to the synagogue dressed as a rabbi, wearing a turban (laffa) and a coat (jubba), some Jewish attendees decided to stop praying as a sign of protest. But he celebrated the same year the wedding of a Jew from Sidon with a second wife from Tel-Aviv.Footnote 54 In 1940, the CCS finally acted decisively to strip Musa Braun of his title and function (bi-ʿazlihī min waẓīfatihī) of chief rabbi. “The president would then inform the chief rabbi of the Lebanese Republic in Beirut which we consider to be bound to religiously, and to the communal council of Beirut administratively, of our decision.”

Figure 1. Musa Braun's business card as “Grand Rabbin.” https://www.facebook.com/BeirutSynagogue/photos/10155578004596025 (accessed June 4, 2021).

By clinging to his title of chief rabbi, Musa Braun was arguably behaving according to former leadership practices in the city, when the rabbinical institution could be negotiated locally. Strong reactions from Beirut and the CCS against Braun's claims show that with the nationalization of the chief rabbinate for Lebanon in Beirut, this negotiation was technically no more possible. Despite the repeated threats and intimidation, however, Braun refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of the centralized religious authority in Beirut, and succeeded in maintaining his practice as the other chief rabbi in Sidon for many years, deliberately challenging and denying the authority of the chief rabbi of the Lebanese Republic based in Beirut. In fact, when he celebrated the wedding of a Cohen from Sidon with a Christian woman for the amount of 600 Lebanese pounds in 1947, he had been usurping the title for twenty-eight years, thus showing remarkable persistence in his opposition to Beirut.Footnote 55

A similar contentious case involved the management of the awqāf (pious endowment, plural of waqf) revenues for the Jewish community. As was the case with other non-Muslim communities throughout the Ottoman Empire, Jews used the Muslim waqf institution, even though it was originally not their own, to regulate community revenues.Footnote 56 According to the practice in Ottoman Sidon, a man named Yusuf Shmu'el Nigri was appointed in 1907 nāẓir al-awqāf (administrator of the awqāf) by the religious Sunni court in Sidon (al-Mahkama al-Sharʿiyya al-Sunniya bi-Sayda). After the establishment of the State of Greater Lebanon and Jewish political reforms, Yusuf Shmu'el Nigri's position was maintained in Sidon, as from the perspective of the CCS the man had “been practicing for twenty years with the highest degree of honesty and accuracy,” but this time under the supervision of the Israelite Community Council of Beirut.Footnote 57 A commission of seven members was chosen, and control over all Jewish awqāf became the responsibility of this commission alone, although in practice Yusuf Shmu'el Nigri was still referred to as the nāẓir al-awqāf.

One of his relatives, however, Ibrahim Maʿtuq Nigri, fiercely opposed the CCS's management of the awqāf revenues, for which he also claimed to be the legitimate administrator. Despite the official decision to assign the management of all awqāf to the new Jewish commission, Judge Shaykh Rashid Wahba from the Sunni court in Sidon appointed Ibrahim Maʿtuq Nigri to be administrator for a waqf of the Mosaic community (nāẓir waqf li-l-ṭā’ifa al-Mūsāwiyya) in April 1925. Outraged by the news, the community council of Beirut sent a lawyer to the CCS to initiate a lawsuit against Ibrahim Maʿtuq Nigri. In response, the latter sent a leaflet (nashra) to the CCS in which, according to the minutes, “he insulted the council of Sidon, the religion, the council of Beirut, and the chief rabbi.” The event, the minutes relate, “created great confusion.” The content of these insults is not known, however the leaflet was reportedly published on the walls of several mosques and synagogues, which is indicative of Ibrahim Maʿtuq's efforts to show the support he received from members of other religious groups in Sidon. A few days later, in May, the Sunni court in Sidon also notified several members of the community council in Sidon that they were being taken to court by Ibrahim Nigri, who was accusing them of stealing the money of the waqf for the poor (waqf fuqarā’ al-ṭā’ifa al-Isrā’īliyya). In August of the same year, the president of the Beirut community council, Salim Harari, personally came to Sidon to settle the differences between the CCS and Nigri out of court. Yusuf Shmu'el Nigri and Ibrahim Maʿtuq Nigri consequently signed a contract in which they both agreed to resign from their respective positions of administrator of the awqāf, both of which were recognized by the court, once all the awqāf properties’ renting contracts were stabilized.Footnote 58 Like Braun, Ibrahim Maʿtuq managed to persistently challenge the authority of the CCS and that of Beirut, over a long period of time. By relying on local, interreligious sources of support and arguably former Ottoman waqf practices to reclaim power, he demonstrated a great talent for coping with the new national sectarian order.

Saydawi Jews Against Beirut

The question that now arises pertains to the influence that Ibrahim Maʿtuq Nigri and Musa Braun really exerted over the local Jewish community. Did they represent or speak on behalf of a more generalized dissent within the Jewish population in Sidon against the new national sectarian order, or were they merely acting to serve their own interests? To start with, reading between the lines of the minutes of meetings “against the grain” reveals muted voices of support for Braun and Nigri.Footnote 59 When the CCS decided to take major actions against Musa Braun in February 1940, for example, the minutes stressed that “people who have allegedly elected him to represent them on a civil as well as religious level have since changed their minds.” In other words, Jews in Sidon who openly supported Braun's claims did exist at some point. Similarly, when Judge Wahba was confronted by the CCS about appointing Ibrahim Maʿtuq Nigri administrator for the awqāf, he justified his decision by arguing that the latter presented a petition signed by thirty people supporting his appointment. Finally, and most decisively, despite the repeated attempts from the Jewish central authority in Beirut to undermine the influence of Braun and Nigri, the two men came out first in the 1934 election for the CCS. Ibrahim Maʿtuq Nigri was elected with 32 votes and Musa Braun with 25 votes, whereas the former president, Youssef Politi, was turned down, having received only 12 votes. Musa Braun (temporarily) became vice-president of the CCS; Ibrahim Maʿtuq became secretary, in charge of the awqāf. Footnote 60

The threat that Braun and Nigri represented to the viability and popularity of the CCS also is perceptible in the sources. In October 1932, the CCS asked the governor of South Lebanon to stop accepting requests from individuals outside the CCS, because the only legitimate authority was the community council of Beirut. In the letter, Ibrahim Maʿtuq Nigri and Musa Braun are both portrayed as real dangers to the community.

[The CCS] asked the governor to take into consideration requests coming from the community council of Beirut only . . . and to stop Ibrahim Nigri from meddling in the affairs of the community. . . . The council was informed that certain people present themselves as chief rabbi or nāẓir waqf . . . . The governor should not take this into account because the community (of Sidon) has no chief rabbi and no nāẓir awqāf . . . . The council deals with its . . . awqāf and its unique religious reference is the chief rabbi of the Republic of Lebanon..Footnote 61

In spite of the fact that Musa Braun's and Ibrahim Nigri's voices were systematically silenced in the official records of the council because they were “repeatedly acting against the interests of the community,” it is important to note that they did not literally constitute a threat to the entire Jewish population of Sidon.Footnote 62 They rather represented a threat to the legitimacy of the CCS as a political structure, as well as that of the council in Beirut. These details indicate that discontent in fact existed in Sidon against Jewish official authorities, enabling Braun and Nigri to lay claims of political and religious legitimacy on behalf of Saydawi Jews, even though they arguably acted in their own personal interests. But given the lack of support from their authorities, how might we explain their success?

The way some of these stories are covered by the Jewish Arabic newspaper al-ʿAlam al-Isra'ili is of particular interest here. Although the journal based in Beirut mainly represented the interests of the community in the Lebanese capital, Salim Mann also occasionally covered the situation in Sidon. In fact, the journalist had strong connections with the Nigri family and with Yusuf Politi, as Guy Bracha has shown, and readership in Sidon was important.Footnote 63 In several instances, Salim Mann, although he initially backed the official councils, brought a more nuanced perspective to the tensions between Sidon and Beirut. In at least one instance, the title of chief rabbi was used to designate Musa Braun, despite the council's official position, and even though the journal originally had sided with it.Footnote 64

Similarly, with regard to the conflict over the Jewish awqāf, Salim Mann first fiercely supported Beirut and the CCS, but later worked toward finding a compromise. In the early phase, the story was covered from the point of view of the official councils alone. In May 1925, Mann expressed outrage at the appointment of Ibrahim Maʿtuq Nigri as nāẓir al-awqāf by the Sunni court of Sidon, given that the CCS was in his eyes the only legitimate ruling entity representing the Israelite community and its awqāf: “We thought it was a joke, but our Saydawi friends have confirmed that this is true.”Footnote 65 However, in the following issue, a brief note in the form of a disclaimer mentioned a letter the journal had received opposing this point of view. As Salim Mann was traveling to Damascus for a few weeks, the whole case was postponed until his return. In June, an article entitled “A Sahih Hadha?” (Is That True?) covered the whole story, this time from a completely new angle, expressing the editor's mounting doubts.Footnote 66 Finally, Ibrahim Maʿtuq Nigri was even invited to respond “in his capacity as legal wālī for all awqāf of the Israelite community.” Nigri argued that the community had never acknowledged the authority of Beirut: “The community rules itself by itself.”Footnote 67

Chief editor Salim Mann's change of attitude indicates that Nigri was not, it seems, the only one to support this point of view. A few years later, in September 1932, the Nigri case was again discussed by al-ʿAlam al-Isra'ili in the context of tensions between two opposing camps. One camp was led by Youssef Politi, president and representative of the CCS, and the other by Nigri and his followers. The president, Politi, stood accused of corruption and Nigri of “looting” the waqf funds. Salim Mann tried not to take sides in the dispute: “Al-ʿAlam al-Isra'ili implores its brothers to call upon friendship, unity and sacrifice . . . in the service of the community.”Footnote 68 But once the breach was open, new accusations poured in. At one point, the tension was so high that the community council in Beirut submitted a petition to the president of Lebanon, Charles Debbas, for intervention. The affair started with al-ʿAlam al-Isra'ili publishing an anonymous letter from “a concerned Israelite” who expressed doubts about the transparency of the CCS. Despite the journal's continued efforts to reaffirm the legitimacy of the CCS, an article entitled “Where does the Waqf . . . Money Go in Sidon?” (Ayna Tadhhab Amwal . . . al-Awqaf fi Sayda) was published, followed by two others anonymously signed by “a truly neutral Israelite” (Isrā’īlī mutaḥāyid) discussing the same topic.Footnote 69 Although attempting to stay “truly neutral,” the articles demonstrated the general dissatisfaction with the Israelite Community Council in Beirut, and the absence of acknowledgement for its authority over Sidon:

I am an Israelite Saydawi (Ṣaydāwī Isrā’īlī), completely neutral and I do not interfere at all with the two parties. Youssef Politi's party has asked the chief rabbi in Beirut and the community council to come to Sidon for the elections. But I do not understand the relation between the community council in Beirut and the affairs of the Israelite community in Sidon. What right does it have to interfere in our . . . affairs? We were not the ones who elected it so it has not even the smallest authority over our community. If Beirut wants to interfere in the affairs of Sidon, then the Jewish population of Sidon should participate in the elections of the community council in Beirut the same way the community in Beirut does [in Sidon].Footnote 70

Finally, other strategies attempted to bypass Beirut's authority. Evidence reveals that influential Jews from Sidon negotiated directly with the Lebanese administration for their own political empowerment in the region, rather than consulting with the Jewish council in Beirut. In particular, Salim Mann wrote a sarcastic note in the column for local events in al-ʿAlam al-Isra'ili about the appointment of Jews from Sidon to the administrative council for the governorate of South Lebanon in 1925. Two people were appointed to the position, Musa Murad Lawi and Musa Braun.Footnote 71 With bitter irony, Salim Mann expressed hope that the government would act in a similar manner to the governorate of Beirut by appointing more Jews to its administrative council. After all, Mann argued, today the greatest Jewish merchants and bankers are in Beirut, no longer in Sidon. Behind the irony, however, Mann could barely hide the general outrage triggered by the news within the community in Beirut of Jews from Sidon going over their heads to gain political power without them.Footnote 72

In Sidon, a tense political battle was playing out between Jewish official authorities trying to impose their rule from Beirut and some individuals, Musa Braun and Ibrahim Maʿtuq Nigri most saliently, trying to impose theirs in Sidon. In this battle there was no obvious winner, and the rest of Sidon's Jewish community most probably positioned itself somewhere in between the two camps. Nevertheless, two dimensions—at least—need to be considered here to understand the complex processes of constructing differences and similarities within the Jewish community in Lebanon. One is sect-specific: the Jewish community councils in Beirut and Sidon envisioned their communities as primarily bound by their sect (al-ṭā’ifa). Its members used the reconfiguration of political structures provided by national sectarianism—or sectarianism from above—to claim from below legitimate authority over all Jewish communities in the country. The other is space-specific; the way some Jews in Sidon envisioned their authority depended primarily on localized dynamics of power and influence, partly inherited from Ottoman administrative practices and partly from their social or interreligious experiences rooted locally. These categories are not mutually exclusive; the fact that Nigri and Braun used space-related dynamics to reclaim power in their own names does not mean that they did not also make use of other forms of sectarianism. And, inversely, space-specific power struggles were arguably at stake in Beirut, too. However, as a result of these complex processes, new forms of sectarianism produced by the national frame and implemented by Jewish community councils to subject Saydawi Jews to Beirut were met with persistent resistance, because other expressions of solidarity involving Sidon's localized identity were also at stake.

Acknowledgments

I would like to warmly thank the anonymous peer reviewers, as well as IJMES editor Joel Gordon, who offered incisive yet encouraging feedback. Their comments helped me strengthen my argument and improve my analysis. The colleagues who attended the Jews in Muslim Majority Countries conference at the Jewish Museum in Berlin in 2017 offered invaluable and thoughtful comments on an earlier version of this paper. Also, for their feedback or precious time spent reading the first draft, I wish to express my heartful thanks to Frédéric Abécassis, Seth Ansizka, Philippe Bourmaud, Guy Bracha, Ahmad Dallal, Efrat Gilad, Iyas Hassan, Anaïs Massot, Akram Zaatari, and Zvi Zohar. Finally, I am enormously grateful to Yolla Polity for her time, patience, and trust while sharing her family history and archives with me.