In 18th-century Arabia Muhammad Ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab (d. 1792), the eponymous founder of Wahhabism, ordered an auto-da-fé of a collection of prayers for the Prophet Muhammad written in the 15th century in Morocco, Dala'il al-Khayrat (Proofs of Good Deeds), because, in his opinion, it was loved more than the Qur'an itself.Footnote 1 The early modern era did see an intensification of the veneration of the Prophet, under the influence of political elites and sufis, and an unprecedented growth in the production of texts fit to feed such devotion, either new works or commentaries on works of the past. The different genres of devotional literature dedicated to the Prophet had been established since the middle ages: supplications and prayers invoking divine blessings upon the Prophet (ṣalawāt), poetry in praise of the Prophet (madāʾiḥ nabawiyya or nabawiyyāt), and narratives of his birth (mawlidiyyāt) and his ascension through the heavens to the Divine Throne (mi‘rāj).Footnote 2 This literature was not designed to be “read,” but to be recited or chanted by an individual (maddāḥ, munshid) or a group, in various spaces and contexts: mosques, sufi lodges (zawiyas), shrines, or private homes, during sufi weekly sessions of remembrance of God (dhikr) or public religious celebrations.

Because of the oral nature of the genre, devotional literature evolved a style in which poetry, rhythm, and melody came together, making such texts easier to memorize and more likely to be used in an almost liturgical way. As a result, works composed by eminent scholars, who were very often sufis, are frequently, for the sake of convenience, classed in catalog indexes as “devotional literature.” This reduces these texts to their function, and does not take account of their complexity, both formal (they demonstrate a great richness of illustration and symbolic language) and in terms of their theological and doctrinal content.Footnote 3 This devotional literature may be doctrinal and literary, performative and ritualistic, thaumaturgic and artistic, making it an appropriate field of study for many different academic disciplines.

My approach is that of a historian of sufism. In this article I examine the ways in which such texts were critical in the distribution to popular audiences (who were still immersed in an oral culture) of the major doctrinal themes that were developed by the early sufis, fully elaborated by Ibn ‘Arabi (d. 1240) and then spread by those who followed him. Although it praises the Prophet as God's elect, savior, and seal of the prophets, this literature also describes him as a primordial and cosmic reality (ḥaqīqa Muḥammadiyya), as the light that gave birth to the world (nūr Muḥammadī), and as a perfect being (insān kāmil) who brings together in his person divine realities and human qualities.Footnote 4 Present for all eternity, the Prophet continues to act on and intercede in this world, directly or through his heirs, the saints (awliyā’ Allāh), until the day of the last judgment, when he will intercede for all humanity (al-shafī‘ fī jamī‘ al-anām). Over the long term and culminating in the 15th century, these doctrines of the metahistorical reality of the Prophet, and of sainthood inherited through Muhammadan prophecy, became established among the general populace as much as within the ranks of political elites.

Beginning in the middle of the 15th century, the above-mentioned collection of prayers upon the Prophet—composed in Morocco by Muhammad ibn Sulayman al-Jazuli (d. 1465) and later so reviled by the Wahhabis—whose complete title is Dala'il al-Khayrat wa Shawariq al-Anwar fi Dhikr al-Salat ‘ala al-Nabi al-Mukhtar (Proofs of Good Deeds and Brilliant Burst of Lights in the Remembrance of Blessings on the Chosen Prophet), spread through the Islamic East and over two centuries acquired a quasi-sacred status and virtually international distribution.Footnote 5 In studying this text, which is both emblematic and exceptional, my first aim is to cast light on the novel political, economic, and institutional conditions surrounding the international circulation of Arabic-language literature of devotion to the Prophet, and to explore the religious and political implications of these conditions and this circulation for sufis in the early modern era. I will elucidate the central importance of Morocco and Egypt in the production and diffusion of this literature across the rest of the Maghreb, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Islamic East. These two countries occupy a particular position in the development of devotion to the Prophet. At the beginning of the 13th century they pioneered Sunni celebration of the anniversary of his birth (mawlid), and, later, the organization of a new form of liturgical practice that took place within mosques: collective assemblies for prayer of blessings on the Prophet (majlis ṣalāt ‘alā al-nabī). There is evidence for such assemblies beginning in the second half of the 15th century. The present article is based on earlier wide-ranging original research established by the German-language Orientalist school, which had an early interest in devotion to the Prophet, and in its diverse expressions and their historical impact.Footnote 6 I also build on the work of specialists in sufism such as Fritz Meier, who was the first to grasp the role of invoking blessings on the Prophet (taṣliya) by focusing on premodern sufi tariqas of the Islamic West. Meier's research was pursued and completed by Amine Hamidoune in his unpublished doctoral thesis.Footnote 7 The work of historians of art and material culture also has been essential to understanding the many uses of prayer books as objects of devotion.Footnote 8

The first part of this article presents a lengthy chronology of this literature to illustrate that the 15th century was the culmination of the social integration of this veritable dogma of Prophetic presence (a term, Mohammeddogmatik, adapted from the German Orientalist Tilman Nagel).Footnote 9 The themes of this literature were established during the 13th century, then reappropriated and reformulated during the 15th century in a new context: sufis and their institutions were expanding in unprecedented ways, bringing them new social and political weight and access to the realms of power.Footnote 10 Now, the religious authority and social role of the sufis were legitimized by their proximity not only to God (the walāya, divine friendship) but to the Prophet who inspired and guided them. Such was their authority that they could present themselves as being like another Muhammad, with all the attributes of guidance and salvation that this implied. Final intercession for the salvation of souls (shafā‘a) remained the domain of the Prophet himself; however, sufis, through their prophetic heritage, participated in his intercession and were solicited by the faithful for this purpose, as well as for intercession in daily life here below. Consequently, they wrote most of the texts encouraging the devotional practices that actualized the presence of the Prophet. Sultans believed as much as the masses did in the supernatural powers of saints, especially the power of prediction (firāsa), and they were attached to these men by deep religious conviction, as well as for pragmatic reasons of political legitimization. Like the Mamluks and Timurids before them, the Ottoman sultans demonstrated a genuine devotion to sufis, and sought to approach their model of holiness, as demonstrated by extensive recent historiography on the links between sufism and politics in the modern period.Footnote 11

In the second section of this article I will undertake to describe elements of the structure and content of the Dala'il that gave it an impact so massive that it eventually eclipsed the numerous other collections in circulation at the time and became the model for many others. It is important to remember that alongside texts such as the Dala'il, which are very well known in the Sunni Islamic tradition even to the present day, there was a considerable and flourishing written and oral literature singing the praises of the Prophet and his love and pleading for his intercession.Footnote 12 This literature was written in a style that borrowed from Arabic poetry or drew on its own poetic register, and it underlines the link between the metaphysical doctrine of the cosmic reality of the Prophet and the relationship of love and gratitude toward the well-beloved and gift of God (ḥabīb Allāh, hadiyat Allāh) that this doctrine represents. I will then focus on one of the central themes of the Dala'il, that of the waking vision of the Prophet granted to sufis, to show how it reveals ways in which their authority in society, and that of their institutions, was probably unprecedented at the dawn of the modern era.

Literature of Devotion to the Prophet: Genres and Periods

Religious history rarely follows the sometimes rapid twists and upsets of political history. Instead, it unfolds over the long term, identifying the transmission, exchange, and appropriation of ideas and practices connected to such ideas. The classic themes of devotional literature relate to the Prophet's life (edifying and hagiographical accounts, inspired by the Sira written by Ibn Hisham [d. 828/33] and based on a work by Ibn Ishaq [d. 767/68]); to his beauty and the perfection of his character (inspired by shamā’il literature); to proofs of his prophecy (dalā’il al-nubuwwa) such as his night journey to Jerusalem and his celestial ascent (al-isrāʾ wal-miʿrāj); to love for him, longing for him in his absence, and the desire to see Mecca and Medina and visit him there; and finally to the hope of salvation through his intercession. The composition of devotional works occurs in response to spiritual, educational, and political necessities. New devotional texts appear at moments of anxiety or crisis. During Islam's early centuries theological debates about the status of the Prophet were concomitant with a wider evolution in Sunni thought. Recourse to the infallible teachings of the Prophet was sought against Mu‘tazili and rationalist tendencies in general, and the hadith was recognized as sacred. One book that had a determining importance, even if one considers only its extraordinary circulation throughout the Sunni world, was al-Shifa bi-Ta‘rif Huquq al-Mustafa (The Cure Being an Acknowledgement of the Rights of the Chosen One), also known under the title Kitab Hujjat al-Islam (The Book of the Proof of Islam), by Qadi ‘Iyad (d. 1149), who came from Ceuta, in the Maghreb. The writing of this text was affected by the political context in which it took place: in the face of the many dangers posed by the Almohad Mahdi (Almohad Caliphate, 1130–1269) and his claim of infallibility; by the Shiʿa in Ifriqiya and Egypt (Fatimid Caliphate, 909–1171) who considered their imam to be divine; and by the ideas of the rationalistic jurisprudents (ahl al-ra'y). Qadi ‘Iyad defended the Prophet's superiority above all other prophets and his infallibility (‘iṣma) by virtue of his privileged relationship with God, along with his unique role as intercessor on the final day, and believers’ duty of respect (ikrām) and veneration toward him. This led Tilman Nagel to write that with al-Shifa, the Prophet's wasīṭa, that is to say, the possibility of access to knowledge of the divine order through the Prophet's mediation, becomes a dogma.Footnote 13 But it was beginning in the 13th century, in the context of extensive political upheavals, that devotional literature was amplified and its themes were fixed.

The Establishment of a Genre in the 13th Century

During the 13th century, the history of the Muslim world entered a new era defined by the Mongol invasion, the siege of Baghdad and fall of the Abbassid Caliphate in 1258, and the progressive loss of Islamic possessions in al-Andalus. In these hard times, the figure of the Prophet as a source of succor and mercy here below and in the next life was increasingly at the heart of the religious devotion of the faithful.Footnote 14 The Prophet's birthday, which until this time had been a Fatimid Shiʿi festival, began, with the support of the dynasts in power, to be celebrated in the Sunni Muslim world. This brought rejoicing with it, as well as an entire literature praising the Prophet's unique qualities, virtues, and miracles (madīḥ nabawī), and celebrating the merits of places that were sacralized by his presence (Mecca, where he was born, and above all his final resting place, Medina). With the recital of prayers and blessings on him and his family, it also implored him to intercede. Celebrations of the Prophet's birth were centered around narratives called mawlid (pl. mawlidiyyāt). These verse or prose accounts took their inspiration from the Qur'an, from Prophetic traditions, and from the Sira. They were embellished with accounts of miraculous events that took place before and after the Prophet's birth, his vocation, and his ascent into heaven, alongside details that offered proofs (dalīl, pl. dalā’il) that he was the last prophet, themes drawn from the literature of shamā’i and dalā’il al-nubuwwa. The earliest known mawlid texts came from Andalusia in the 12th century.Footnote 15 Since Ottoman times the mawlid that has been most prized in the Turkish world is Vesilatu'l-necat (The Means of Salvation), composed in Bursa in 1409 by the great poet of the Ottoman language, Suleyman Çelebi (d. 1422?).

The mawlid is a subgenre of al-madīḥ al-nabawī, poetry in praise of the Prophet; the recital of such works was an integral part of the celebrations that marked his birthday. A poem from that period enjoys immense popularity across the Muslim world to this day. Al-Kawakib al-Durriya fi Madh Khayr al-Bariya (Celestial Lights in Praise of the Best of Creation) by the Egyptian Sharaf al-Din Muhammad al-Busiri (d. 1298), commonly called Qasidat al-Burda (The Poem of the Mantle), is the best known of a series of “mantle odes” (the name was coined by Suzanne Stetkevych). This genre goes back to the beginning of Muhammad's predication, with the famous poem Banat Suʽad (Suʿad Has Departed) by Kaʽb ibn Zuhayr (7th century).Footnote 16 The composition of the Burda is based on a dream-vision of the Prophet and a miraculous cure. Busiri, afflicted by hemiplegia, recounts how the Prophet appeared to him in a dream after he (Busiri) had recited a poem in his praise, and wrapped him in his mantle: when Busiri woke up in the morning, he was miraculously cured from his paralysis.Footnote 17 Praise poetry concentrates on the virtues and unique qualities of the Prophet—his generosity and protection, his elevation, the purification of his heart during his childhood—and on his coronation: he is the justification of the universe and its ultimate goal. It recollects the events that shook the world when the Prophet was born, such as the light that emanated from his mother Amina and illuminated the castles of Bosra in Syria, the crashing of idols, the collapse of the arch of the palace of Khosrow in Persia and the extinction of the fire of its temples.Footnote 18

Praise poetry establishes a personal relationship between Muhammad and the believer, who addresses the Prophet directly and begs for his mediation (tawassul) and intercession (tashaffu`) in the afterlife. In practice, it appropriates for religious ends a culture of panegyric that permeated social relationships in premodern Islamic societies. Overlaid upon a genuine economy of praise, in which poets were remunerated for their verbal services and because of their allegiance to powerful patrons, we find an economy of salvation in which the remuneration expected by the one who sings the Prophet's praises, and most fervently expresses his love for him, is protection and intercession on the day of the last judgment. Beginning with Busiri's Burda and under sufi influence, poetry became the most powerful and efficient engine for the spread of the veneration of the Prophet and the saints. The story of the healing of Busiri is the symbolic expression of the power of reciting the Burda which, like the Prophet's mantle itself, is a promise of protection and of healing for body and soul. The talismanic power attributed to this poem became so great that Ottoman sultans had its verses inscribed along the walls of the chamber that contained the mantle, and other Prophetic relics, in the Topkapi palace. In her extensive analysis of the Burda, Suzanne Stetkevych rightly notes that what its reciter seeks is to identify with Busiri's experience and accede to the same spiritual transformation: he saw the Prophet in a dream, and found himself in the Prophet's presence. This explains the poem's great popularity in the sufi brotherhoods.Footnote 19

The fall of the Abbassid Caliphate reinforced the authority of the sufis, as is indicated by the increase in number of hagiographies describing a world order in which the true masters are the saints, who form an invisible government with its own council (dīwān) and hierarchy, above which is the pole (quṭb), the supreme recourse and universal succor (ghawth), the archetype of which is the Prophet Muhammad. Sufis laid claim to an authority superior to that of other religious groups, that of the walāya (divine friendship), as an extension of the prophecy (nubuwwa) developed by the Khorasan mystic al-Tirmidhi (d. 892) and systematized by the Andalusian Ibn ‘Arabi.Footnote 20 The belief that a saint provides his protection to a territory and to the people who inhabit it is a major element in premodern Islamic society, an important model of social organization, and a factor in Islamization that has not been investigated sufficiently.Footnote 21 The sufis attributed the prerogatives of the Prophet to themselves, in life here below, most prominently that of intercession for the salvation of souls. This makes it easy to understand why sufis were the principal authors of texts that supported practices and rituals that would be likely to encourage Prophetic piety, and why they became promoters of the cult of the Prophet at exactly the period during which the first great mystical paths were founded by sufi masters who were considered to be descendants of the Prophet and earthly heirs of his spiritual authority.Footnote 22

The Genre's Renewal in the 15th Century

By the 15th century, ancient genres were enjoying a genuine revival, especially in Egypt and the Maghreb; among these were biographies of the Prophet, literature on “proofs of the authenticity of Muhammad's prophethood” (dalā’il al-nubuwwa) and on “the special attributes of the Prophet” (khaṣā’iṣ al-nabawiyya, traditions relating to the Prophet's legal status and unique qualities). This literature evolved to give more space to the Prophet's unique qualities and miracles, and to the veneration due him. For example, Insan al-‘Uyun fi Sirat al-Amin al-Ma‘mun (The Apple of the Eyes in the Life of the Loyal and Honorable One), commonly known as al-Sira al-Halabiyya, by the Egyptian ‘Ali al-Halabi (d. 1635), overflows with accounts of miracles around the birth of the Prophet that are not found in the biography by Ibn Ishaq.Footnote 23 Al-Halabi's Sira was immediately successful in the Ottoman world. Stripped of lists of chains of hadith transmission, this more literary account made accessible reading, and could be recited during celebrations of the Prophet's birth.Footnote 24 Al-Khasa'is al-Kubra (The Special Attributes [of the Prophet Muhammad]) by al-Suyuti (d. 1505) and al-Mawahib al-Laduniyya fi al-Minah al-Muhammadiyya (The Divine Gifts Contained in the Muhammadan Graces) by al-Qastallani (d. 1517) represent the culmination of a medieval culture that, under sufi influence, made the Prophet more than a simple messenger and exemplary founder of a community whose conduct and actions (sunna) provided legal and social norms: he became a metaphysical figure, a reality that was present for all eternity, a “mercy to the worlds” (raḥmata li-l-‘alamīn, Qurʾan 21:107). Al-Suyuti was a highly respected jurist and well known for his knowledge of the hadith. In his article, “A Resurrection of Muḥammad in Suyūṭī,” Fritz Meier casts light on his role in the theological debates about the death of the Prophet. These evolved progressively toward a belief that the Prophet was still alive in his tomb, and was acting on the world until the day of the last judgment, when he would intercede for all of humanity. The blessings that people invoked upon him reached him.Footnote 25

The practice of invoking God's blessings upon the Prophet and his family, the taṣliya (ṣalāt ‘alā al-nabī), was not specific to Sufis; it had its roots in Islamic tradition and followed the Qur'anic injunction, “God and his angels bless the Prophet, O you who believe, invoke (divine) blessings on him and greet him” (Inna Allaha wa malā’ikatahu yuṣallūna ‘alā al-nabī, yā’ayyuhā al-ladhīna āmanū ṣallū ‘alayhi wa sallimū taslīman, Qurʾan 33:56). Belief in the presence of the Prophet and in the prospect of his intercession at the last judgment led to the elaboration of thousands of formulas of praise and invocations of divine blessings upon him through the centuries. Treatises on the merits of “praying upon” the Prophet (that is to say, pronouncing litanies of divine blessings upon him) appeared as early as the 12th century.Footnote 26 The earliest account of his birth known today, Durr al-Munazzam fi Mawlid al-Nabi al-Mu`azzam (The String of Pearls: The Story of the Birth of the Revered Prophet) by Abu al-‘Abbas al-‘Azafi (d. 1236), originating in Morocco, contains a chapter on the virtues and merits of praying for the Prophet.Footnote 27 But here too, as we have observed for other genres of literature on the Prophet, the 15th century was the turning point. Drawing on the writings of his predecessors, the Egyptian al-Sakhawi (d. 1497) composed the largest synthesis to date about prayer on the Prophet, called al-Qawl al-Badi’ fi-l-Salat ‘ala al-Habib al-Shafi‘ (The Radiant Discourse Concerning the Invocation of Blessings on the Beloved Intercessor). During the same period, the Moroccan sufi al-Jazuli (d. 1465) compiled what is still the best-known collection of prayers blessing the Prophet: Dala'il al-Khayrat wa Shawariq al-Anwar fi Dhikr al-Salat ‘ala al-Nabi al-Mukhtar.Footnote 28 Although it was put together from older sources, the diffusion of the Dala'il marked a turning point because it may have been the first collection of prayers on the Prophet to be used in sufi rituals. The prayers therein were divided into sections (aḥzāb) specifically for recitation each day of the week. Al-Jazuli initially wrote this handbook, probably in 1453, for disciples in his sufi brotherhood, a branch of the Shadhiliyya.Footnote 29 This was a time of crisis: almost nothing was left of al-Andalus, the Portuguese were threatening the Moroccan coastline, and the country was plunged into the political chaos of the decline and fall of the Marinid dynasty (1269–1465).Footnote 30 Al-Jazuli presented himself as one who continued the Prophetic mission and defender of the Dar al-Islam, working to compile and report traditions that exhorted the faithful to pray on the Prophet; this was the spiritual exercise par excellence, but also a rallying cry for al-Jazuli's disciples, who took part in the defense of the coasts in the ribat (monastery-fortress). The Dala'il initially spread in the scholarly circles in Fez linked to the Shadhiliyya. Its first collective recitations were organized by ‘Abd al-‘Aziz al-Tabba’ (d. 1508), a disciple of al-Jazuli, in the Madrasa al-‘Attarin in Fez toward the end of the 15th century. The Dala'il had to be recited aloud. The collection very quickly spread to the rest of the Maghreb. It is cited by the scholar from Tunis, Barakat al-‘Arusi (d. 1492), who also used it as a model when he wrote his own collection divided into twenty-four prayer sessions (majālis), Wasilat al-Mutawassilin bi-Fadl al-Salat ‘ala Sayyid al-Mursalin (The Support of Those Who Seek Intercession through the Merit of Prayer in Favor of the Master of the Messengers), composed in 1473. According to their author, the prayers were collected to be recited on Fridays, providing evidence of one of the earliest assemblies for prayer on the Prophet in the Maghreb.Footnote 31 In Mamluk Egypt and in Syria the ground was laid for the reception of the Dala'il because sessions of remembrance (dhikr) of the Prophet, using formulas of divine blessings upon him, already existed there. In 1492, Nur al-din al-Shuni (d. 1537) instituted an all-night ritual of collective prayers devoted to the Prophet at al-Azhar mosque, a ritual that was attacked by some literalist jurists (fuqahā’).Footnote 32 These nocturnal assemblies for “prayer on the Prophet” quickly spread into other Arab cities of the Ottoman empire, such as Damascus, where, according to the historian al-Muhibbi (d. 1699), they were introduced into the Umayyad mosque in 1563 by a disciple of al-Shuni, ‘Abd al-Qadir al-‘Ataki (d. 1605). The practice known by the name of al-maḥyā had its own shaykh al-maḥyā al-sharīf al-nabawī and its sajjadat al-maḥyā.Footnote 33 The ritual was attested to by Ibn Hajar al-Haytami (d. 1566) in Mecca during the first half of the 16th century.Footnote 34

Diffusion, Reception, and Uses of the Dala'il in Ottoman Context

Thus the Dala'il was not the only Arabic collection of prayers circulating at this time. In his PhD dissertation, Amine Hamidoune has listed hundreds of them, and their commentaries, appearing from 1500 to 1900, peaking in the 18th and 19th centuries. Two-thirds of the mentioned works display a form of standardization that would be fixed by the advent of printing.Footnote 35 However, the Dala'il surpassed all of these in popularity, especially in the Turco-Ottoman sphere. Guy Burak has drawn attention to a note, dating from the first half of the 18th century, written in the margins of a short section on al-Jazuli in the bibliographic encyclopedia Kashf al-Zunun ‘an Asami al-Kutub wa-l-Funun (The Removal of Doubt from the Names of Books and the Arts), by Katib Çelebi (Hajji Khalifa; d. 1657), that bears witness to this: “Assiduously recited in the East as in the West, especially in Anatolia (bilād al-Rūm), the Dala'il al-Khayrat is a sign among the signs of God (āya min āyāt Allāh).”Footnote 36 Burak rightly underlines that the existence in the 17th and 18th centuries of a large number of Turkish-language commentaries intended to explain the content of the Dala'il to the elite as much as to commoners is a sign of the popularity of this collection in Ottoman lands. One commentary in particular, by Muhammad al-Mahdi al-Fasi (d. 1698), Matali‘ al-Massarat bi-Jala’ Dala'il al-Khayrat (The Rise of Joys in Clarifying the Signs of Benevolent Deeds), contributed immensely to the popularity of al-Jazuli's work. Illustrated Ottoman copies of it were in circulation during the 18th and 19th centuries.Footnote 37 The Dala'il spread to the east as far as Indonesia and Central Asia, where it was memorized in dala'il-khanas or salawat-khanas, lodges established expressly for that purpose.Footnote 38

Although the collection circulated quickly through the rest of the Maghreb over the course of the second half of the 15th century, it reached the Islamic East later, via channels of transmission that remain obscure. However, the fact that it appears in the heart of the Ottoman Empire during the 17th century is no coincidence; this period saw a renewal of the circulation of people from the Maghreb toward the Islamic East thanks to the new imperial context and to economic growth that encouraged greater mobility for people and goods. The increasing presence of Maghrebis in Cairo beginning in the 17th century is linked to factors that are religious and commercial: pilgrims to Mecca from the Maghreb (and sub-Saharan Africa) joined the caravan in Cairo, and Maghrebis, especially the merchants of Fez, played an important role in international commerce.Footnote 39 As men circulated, so did books. Travelers from the Maghreb used their stays in Cairo to exchange and buy books at a time when the production of manuscripts was increasing in the city, already presaging the position it would reach in the 19th century as the biggest center of printing in the Arab world.Footnote 40

Al-Jazuli's collection was written to be recited aloud, initially within the circle of disciples at a time when sufism was expanding from the zawiyas into the mosques. It was heard by the wider public during the weekly recitation sessions and during religious festivals, especially the annual celebration of the Prophet's birthday. Nelly Hanna, who has examined the spread of books among social groups outside the elite in Ottoman Egypt, proposes several interesting hypotheses on the duality between oral and written culture: “Oral tradition was so strong and so rich as to allow certain types of person who, in spite of the absence of reading and writing skills, might have a broad culture obtained through the diverse forms of oral transmission.”Footnote 41 This applies as much to scholarly as to popular culture. She adds that “with the spread of cheap paper came a trend of writing down on paper what had previously been oral literature.”Footnote 42 Her research in the registers of inheritance records of Ottoman-period court archives in Cairo confirms the results of research done on inheritance records in Ottoman Damascus by Colette Establet and Jean-Paul Pascual, who showed that there was a high proportion of books of devotion, and of copies of the Dalaʾil in particular, in the private libraries of Cairo and Damascus.Footnote 43 In 18th-century Cairo, the Dalaʾil al-Khayrat was indeed the most-copied book. According to Hanna it can legitimately be called a best seller: it is the book that everyone had to own, regardless of social class. The publishing market circulated different editions at prices to suit any pocket. The popularity of the Dalaʾil allowed Cairene copyists to make a living essentially from copying this single text; there also are waqf documents of the period that stipulate its daily recital in mosques, in the same way as the Qur'an.Footnote 44

Recent work by historians of art and religious materiality have provided crucial information on the relationships between the devout and the prayer book as an object of devotion. As with the Cairene manuscripts examined by Hanna, codicological studies by Hiba ‘Abid on Maghrebi manuscripts of the Dala'il reveal a great variety of models—from the most luxurious and richly illuminated copy to the cheapest—and many different formats, from imposing tomes intended to remain in one place (in a mosque or home) to pocket volumes that were carried on the person.Footnote 45 In the Maghreb too, the prayer book affected all levels of society, in places becoming one of the most-read religious texts after the Qur'an, and one which, like the holy book, had a sacred status. It was the only religious book apart from the Qur'an to have illustrations: images of the mosques of Mecca and Medina, and of the Prophet's tomb in Medina (al-rawḍa al-sharīfa, “the noble garden”), with his pulpit (minbar), as a figurative representation of the hadith: “Between my grave and my pulpit lies one of the gardens of Paradise” (mā bayna qabrī wa minbarī rawḍatun min riyāḍi’l al-janna).Footnote 46 The form of the Dala'il influenced the evolution of an Ottoman book of prayers that became famous between the 16th and 19th centuries: the En‘am-i Sherif. In its early period the En‘am was made up of chapters from the Qur'an and various invocations; by the 17th century it contained calligraphic composition that included the description of the physical beauty and moral qualities of the Prophet, known as ḥilye. From the end of the 18th century and throughout the 19th illustrations appeared, representing the Prophet's relics.Footnote 47 These relics were believed to be traces (āthār) of his continual presence and endowed with baraka (divine blessing). In her study of an Ottoman illustrated prayer manual, Christiane Gruber demonstrates that these images were touched and kissed.Footnote 48 The Dala'il and the En‘am-i Sherif were often combined in a single book, sometimes alongside Busiri's Burda, Hizb al-Bahr (Litany of the Sea) by Abu al-Hasan al-Shadhili (d. 1258), and the Hizb al-A‘zam (The Supreme Litany) by the Hanafi scholar ‘Ali al-Qari (d. 1605).Footnote 49 These popular collections provided support for devotional practices and were themselves objects of devotion, believed to possess thaumaturgic and talismanic properties.

The success of the Dala'il in Ottoman Turkish societies was part of a much larger production and consumption of devotional objects and other forms of religious materiality associated with the Prophet Muhammad in the Ottoman lands. The same virtues of protection and benediction are attributed to the famous ḥilye (literally “ornament”), short descriptions of the inner and outer beauty of the Prophet, beautifully produced by the greatest Turkish calligrapher of the end of the 17th century, Hafiz Osman (d. 1698). Inscribed within circles beneath which was written in large letters the Qur'anic inscription “Mercy to the worlds” (a reference to the verse, Wa mā arsalnaka illā raḥmata lil-‘alamīn, We have not sent you, save as a mercy to the worlds, Qurʾan 21:107), these texts were sought after in Ottoman society. At the end of the 16th century, the Turkish poet Khaqani Efendi (d. c. 1600) wrote a poem based on the Prophet's ḥilye, additionally devoting many words to the numerous benefits and apotropaic virtues conferred on the owner through reading, listening, or just possessing this text. Not only would one be saved from the fires of the last judgment, but Satan would never enter one's home; this explains why even today the ḥilye is hung on the wall inside houses. It also provided protection against illness, and it brought rewards equivalent to those afforded by a pilgrimage to Mecca. Last but not least, it was a mark of love for the Prophet.Footnote 50

The only other Arabic-language devotional text that came close to rivaling the Dala'il in international circulation during the Ottoman period was al-Barzanzi's Mawlid. By giving a central role in the official celebration of the Prophet's birth to the recitation of Suleyman Çelebi's Vesilet en-Necat, a practice attested to from at least as far back as the 16th century, the Ottoman sultans propelled this already widespread genre to its apogee. ‘Iqd al-Jawhar fi Mawlid al-Nabi al-Azhar (The String of Pearls on the Blazing Birth of the Prophet) by Ja‘far b. Hasan al-Barzanji (d. 1764) is better known as Mawlid al-Barzanji. The renown of this text and its extensive distribution were connected to its historical context and the place in which it was written, Medina, the intellectual crossroads of the Muslim world; this probably facilitated the spread of al-Jazuli's Dala'il, especially toward Asia.Footnote 51 Ja‘far al-Barzanji, a scholar of Kurdish origin who was born in Medina and died there, belonged to an influential Medinese family, the Barzanjiyya, which was at the center of an international network of sufi ʿulamaʾ that was profoundly influenced by the thought of Ibn ‘Arabi. A jurist and Shafi‘i mufti of Medina (this position was occupied by members of his family until the middle of the 20th century), he also was imam of the Mosque of the Prophet.Footnote 52 Although he wrote numerous other texts his name is linked to his Mawlid and to another equally famous devotional work, the Qissat al-Mi‘raj (The Story of the Miraculous Ascension) an account of the Prophet's celestial ascension; the two texts are often sold together in African and Southeast Asian bookshops.Footnote 53 The mi‘raj genre derives from the mawlid, and can be written in prose or verse. It is recited on the 27th night of the month of Rajab and celebrates the Prophet's ascension into the heavens and as far as the threshold of the divine presence (And was at a distance of two bow lengths or nearer, Fakāna qāba qawsayni aw adnā, Qurʾan 53:9). Narratives of the celestial ascension are usually structured around three miraculous episodes: that of the cleansing by angels of all sin from the Prophet's heart (either through ablution or, as in Barzanji, by the opening of his chest); that of the night journey (isrā’) from Mecca to Jerusalem, mounted on a winged horse called Buraq; and finally that of the actual ascension from one heaven to the next until the seventh heaven (the Lotus of the limits, sidrat al-muntahā). In the course of this journey Muhammad visited paradise and hell, appeared before God, and returned to Mecca. The Turco-Ottoman world was quite infatuated with this particular episode in the Prophet's life, and the genre inspired many poets, calligraphers, and painters.Footnote 54

Using examples from the Dala'il, I will now examine the themes of this important literature, which aimed both to elicit love and devotion for the Prophet and inform readers of his standing with God. This genre spreads teachings about the Prophet as a perfect being, who realized the divine attributes and through whom divine mercy might be channeled by an intercessor through his (the Prophet) rank (jah, maqām) with God, and as the one who offered the possibility of being heard to those who prayed to him. Produced by Sufis, this literature was addressed to the commoners (‘āmma) as much as to a spiritual elite that was uniquely placed to grasp its initiatic significance.

A Breviary on Muhammad's Prophethood

Why did the Dala'il al-Khayrat collection of prayers acquire such immense popularity throughout the Sunni world, and how is this book important for those who seek to understand the history of religious piety during this period? The collection's success was due to its literary style, structure, and ritualistic function. Unlike the doctrinally dense sufi prayers of the medieval period, with their allusive and symbolic style that was accessible only to initiates, al-Jazuli's prayers were easy to grasp, even for the less literate classes, and their simple style was intended to make them easy to memorize. In the introduction (muqaddima) to his collection, al-Jazuli clearly expresses his objective: he wants to bring together in dhikr form all earlier devotional works and invocations drawn from hadith collections to facilitate their memorization. Therefore, he produces “a readable text, unburdened by chains of transmission” (maḥdhufa al-asānid li-yashula ḥifdhuhā ‘alā al-qārī).Footnote 55 The organization of the collection differs from one copy to the next, and in different editions, but it generally follows a clear sequence, starting with an overture (iftitāḥ) that invokes God by His ninety-nine beautiful names; this is followed by an introductory prayer (du’ā’ al-iftitāḥ; translated later) and then by a chapter listing more than thirty hadiths that are claimed to be authentic (ṣaḥīḥ) and relate to the virtues, benefits, and rewards in this world and the next of prayers of blessing for the Prophet (faṣl fi faḍl al-ṣalāt ‘alā al-nabī).

Then comes a list of 201 of Muhammad's names (asmā’ sayyidinā wa mawlānā Muḥammad), to allow the reader to know the Prophet better, understand his unique attributes and qualities, and picture them.Footnote 56 This list sums up the theological and mystical doctrines concerning the person of Muhammad: it underlines the Prophet's elevated rank (al-maqām al-maḥmūd/al-daraja al-rafī‘a), his mercy (nabī al-raḥma, mu‘tī al-raḥma), his assistance (gawth/ghiyāth), and, finally, his intercession on the day of judgment (shafī‘ al-umma) as a function of his divine election (al-mukhtār). In the subsequent passages, at the beginning of which the author specifies his underlying intentions in composing this collection, more than four hundred prayers are divided into eight sections (ḥizb, pl. aḥzāb, an appellation generally associated with the Qur'an, which is divided into sixty aḥzāb), each of which itself is divided into quarters (arbā’) and thirds (athlāth). Each ḥizb corresponds to one day of the week, and their weekly recitation, from one Monday to the next, is perfectly regulated. Hiba Abid explains that the abundance of illuminations throughout the pages of the manuscripts served as aids to memory, and that the layout helped the reciter arrange and understand the prayers visually.Footnote 57 As described by Amine Hamidoune, almost a hundred of these prayers speak of the names and attributes of the Prophet, recalling his physical beauty and moral qualities, the proofs of prophethood, and his miraculous abilities. The prayers are repetitive and share a similar structure; in addition to variations on the Abrahamic prayer (al-ṣalāt al-Ibrāhimiyya: Oh God, bless Muhammad and the family of Muhammad as You blessed Abraham and the family of Abraham) and repetition of the taṣliya (ṣallā Allāhu ‘alayhi wa salam, God Bless him and lend him salvation), the principle corpus is composed of relatively short and simple prayers beginning with the formula Allāhumma ṣallī ‘alā (O God, send blessings upon), to which are added variants relating to a name or attribute of the Prophet:

The use of rhyming prose and alliteration creates a musical feel that makes the prayers easy to memorize, and so encourages their ritualization and quasi-liturgical use. The collection borrows its poeticism, lyricism, and emotional power from the praise poetry addressed to the Prophet, and it is organized around an individual and privileged relationship with the Prophet, whom the believer addresses directly, humbly, and submissively, seeking the Prophet's mediation and expressing yearning and desire to see him. The supplication (du’ā’) attributed to al-Jazuli that ends the recitation of the names of Muhammad (khitām al-asmā’) is worth examining, for it is written in a style that evokes the ḥijāziyyāt poems that were particularly prevalent in the Maghreb; these poems dealt with the yearning due to separation and the desire to pay a visit to the beloved Prophet in his rawḍa in Medina:

Salāmun ‘alā qabrin yuzāru min al-bu‘di / Salāmun ‘alā al-rawḍati wa fīhā Muḥammadi / Salāmun ‘alā man zāra fil-layli rabbahu / Fa-ballaghahu al-marghūba fī kulli maqsadi / Salāmun ‘alā man qāla lil-ḍabbi man anā / Fa-qāla rasūlu Allāhi anta Muḥammadi / Salāmun ‘alā al-madfūni fī arḍ Ṭaybata / Wa man khassahu al-Raḥmanu bil-faḍli wal-majdi / Nabiyyun ḥabāhu Allāhu bil-ḥusni wal-bahā / Fa-ṭūbā li-‘abdin zāra qabra Muḥammadi / Āyā rākiban naḥwa al-madīnati qāṣidan / Fa-balligh salāmī lil-ḥabībi Muḥammadi / Fī rawḍatihi al-ḥusnā munāya wa bughyatī / Wa fīhā shifā qalbī wa rūḥī wa rāḥatī / Fa-in ba‘udat ‘annī wa ‘azza mazāruha / Fa-timthāluhā ladayya aḥsanu ṣūrati / Unazzihu ṭarfa al-‘ayni fī ḥusni rawḍihā / Fa-yaslū bihā lubbī wa sirrī wa muhjatī / Fa-hā anā yā quṭba al-‘awālimi kullihā / Uqabbiluhā shawqan li-ishfā’i ‘illatī / Wa ṣalli ‘alā quṭb al-wujūdi Muḥammadin / Ṣalātan bihā tamḥū ‘annā kulla zallati Footnote 58.

I greet the grave that one may visit from afar / I greet the rawḍa; it is there Muhammad has his resting-place / I greet the one who was carried in the night to be near his Lord / Who fulfilled expectations with all his aspirations / I greet the one who asked the lizard, “Who am I?” / And to whom [the lizard] replied, “Thou art Muhammad, God's messenger” / I greet the one who is entombed in the scented soil of TaybaFootnote 59 / And the one among us all whom the All-Merciful has heaped with graces and glory / Prophet gratified by God with excellence and splendor / Happy is the servant of God who has visited the grave of Muhammad / O thou, saddling thy mount to travel to Medina / Transmit my greetings to Muhammad the well-beloved / In his sublime rawḍa lie my hope and my aspiration / There lies the healing of my heart and my soul; there lies my repose / If distance keeps me from it, and it is difficult to visit / I picture it for myself in the most perfect of images / My gaze wanders through the excellence of its garden / Straightaway this comforts my heart, my innermost being, and my soul / Here I am, O pole of all the universes / Out of desire I kiss [the earth that shelters his remains] that my pain might be healed / O God, bring down upon Muhammad, the pole of the Being / Grace through which you erase all our sins.

The supplication culminates and ends with a prayer in which the believer begs for the Prophet's intercession:

Allāhumma innī as'aluka wa atawajjahu ilayka bi-ḥabībika al-muṣṭafā ‘indaka, yā ḥabībanā yā sayyidanā Muḥammadu innā natawassalu bika ilā rabbika, fa-ashfa‘ lanā ‘inda al-Mawlā al-‘Aẓīm, yā ni‘ma al-rasūl al-ṭāhir, Allāhumma shaffi‘hu fīnā bi-jāhihi ‘indaka (three times).

My God I call upon Thee and turn to Thee through the mediation of Thy well-beloved, whom Thou hast elected; O Muhammad, our well-beloved, our master, through thee we implore thy Lord, intercede in our favor with the August Master, O purest messenger. My God, accept his intercession by virtue of his rank with Thee.

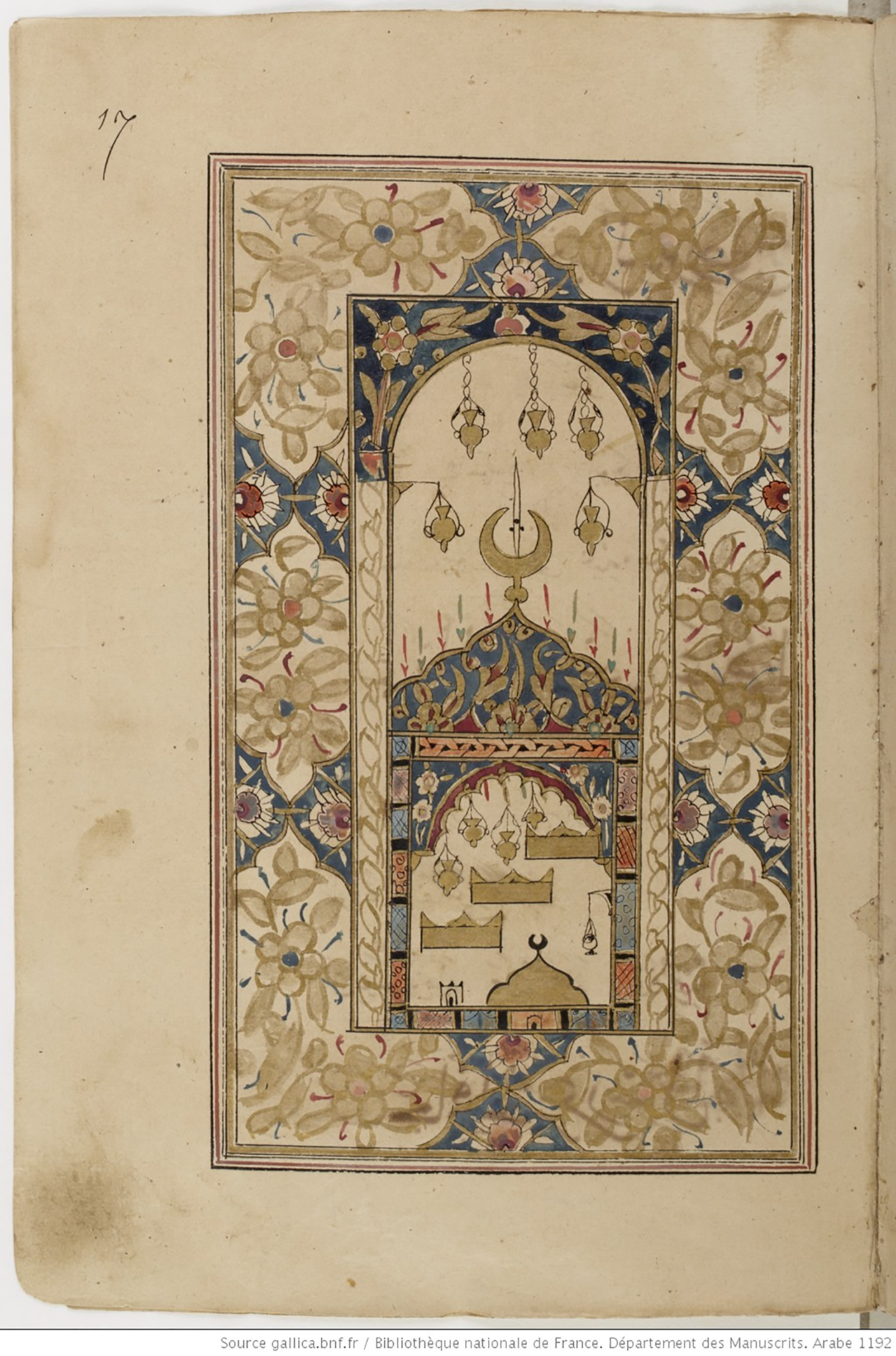

This supplication describes a practice that was widespread in the medieval Maghreb and Andalusia, and that spread from there in the 15th century: letters to the Prophet, sometimes containing poems, were consigned to pilgrims by people in their homelands who could not make the pilgrimage that they might be read aloud before his grave.Footnote 60 To represent the rawḍa “in the most beautiful of images” to those for whom it was impossible to travel to Medina, al-Jazuli followed the recitation of the names of the Prophet with a chapter describing his tomb, within which is inserted a schematic drawing of the funerary chamber in which the bodies of the Prophet, and his Companions the Caliphs Abu Bakr and ‘Umar, are buried: “This is the description of the blessed rawḍa (al-rawḍa al-mubāraka) in which the Prophet Muhammad is buried, together with his two Companions Abu Bakr and ‘Umar.” This drawing is said to have been introduced by al-Jazuli into the autograph copy that he dictated to his disciple, al-Sahli. It indicates the placement of the three tombs, above which is suspended a lamp (qandīl), in reference to the al-Nur sura that describes the Prophet as a bright light (sirāj munīr, Qurʾan 33:46) and to the doctrine of the Muhammadan light (nūr Muḥammadī) (Fig. 1)Footnote 61 The prayer on the Prophet is the best possible method for experiencing the presence of the Prophet, in the hope of being blessed by a vision of him. If all believers may see the Prophet in dreams, only a category of God's elect can see him while in a wakeful state, and speak to him.

Figure 1. Image of the Prophet's burial chamber (rawḍa), Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) MS Arabe 1192 (Turkey, Raǧab 1132)

The Means to the Presence of the Prophet and Union with Him

The contents of the Dala'il are both didactic and experiential. It teaches about the attributes of Muhammad, the proofs of his prophetic status, and his preeminence over all other prophets. Its prayers also provide the best means for the person reciting them or listening to their recitation to experience the presence of the Prophet. Remembering the Prophet helps one imagine him as an almost tangible presence, and may even spark hope of a sleeping or waking vision of him. In the Tuesday section, God is asked to pray for “Muhammad and his family, and for the people of his house, the magnanimous ones” (Allāhumma ṣalli ‘alā sayyidinā Muḥammad wa ‘alā āl sayyidinā Muḥammad wa ‘alā ahl baytihi al-abrār ajma‘īn).Footnote 62 In the chapter on the benefits of the prayer for the Prophet, al-Jazuli clarifies the distinction between ahl and āl, quoting a hadith in which the Prophet is asked: “Who are the people of our master Muhammad's house, whom we have been commanded to love, honor, and treat piously?” (Man āl sayyidinā Muḥammad alladhīnā umirnā bi-hubbihim, ikrāmihim wa-l-burūri bihim?). He [the Prophet] replies: “The people of purity and loyalty, those who believe in me with a sincere faith” (Faqāla: ‘Ahl al-ṣafā’ wa al-wafā’ man āmana biyy wa akhlaṣa). He was once more asked by what signs they were recognized, and he said: “They put love for me above all other love and their spirits are occupied by invoking me, after invoking God.” (Faqīl lahu: ‘wa mā ‘alāmatuhum? Faqāla: īthāru maḥabbatī ‘alā kulli mahbūb wa ishtighālu al-bāṭini bi-dhikriyy ba‘d dhikr Allāh).Footnote 63 When speaking of this hadith, al-Jazuli expresses an idea that al-Tirmidhi had introduced and Ibn ‘Arabi had elaborated, according to which the ahl al-bayt designates the spiritual descendants of Muhammad, saints whom al-Tirmidhi called the “truthful ones” (siddiqūn) or the pillars (awtād) of the Prophet's community (umma).Footnote 64 However, it is in the work of Ibn ‘Arabi that we find this distinction between āl and ahl. As Claude Addas explains, if ahl al-bayt refers to the Prophet's descendants in the flesh, for Ibn ‘Arabi the āl Muhammad designates those who are most intimate with him and closest to him in faith.Footnote 65 In the opening supplication, al-Jazuli calls them the people of “the supreme station of sincerity and election,” which is that of the Muhammadan inheritance (wirātha Muḥammadiyya):

Allāhummā bi-jāhi nabiyyika sayyidinā Muḥammad ‘indaka / Wa makānatihi ladayka wa maḥabbatika lahu wa maḥabbatihi laka / Wa bi-l-sirri al-ladhī baynaka wa baynahu / As'aluka an tuṣallī wa tusallim ‘alayhi / Wa ‘alā ālihi wa aṣḥābihi / Wa ḍā‘if Allāhummā maḥabbatī fīhi / wa ‘arrifnī bi-ḥaqqihi wa rutabihi / Wa waffiqnī li-ittibā‘ihi / Wa al-qiyām bi-adabihi wa sunnatihi / Wa ijma‘nī ‘alayhi wa matti‘nī bi-ru'yatihi / Wa as‘idnī bi-mukālamatihi / Wa irfa‘ ‘annī al-‘awā’iq wa-l-‘alā’iq wa-l-wasā’iṭ wa-l-ḥijāb / Wa shannif sam‘ī ma‘ahu bi-ladhīdh al-khiṭāb / Wa hayyi'nī li-l-talaqqī minhu wa ahhilnī li-khidmatihi / Wa aj‘al ṣalātī ‘alayhi / Nūran nayiran kāmilan mukammalan ṭāhiran muṭahharan / Māḥiyan kulla ẓulmin wa ẓulmatin / Wa shakkin wa shirkin wa kufrin wa zūrin wa wizrin / Wa aj‘alhā sababan li-l-tamḥīṣi / Wa marqan li-anāla bihā a‘lā maqām al-ikhlāṣ wa-l-takhṣīṣ ḥattā lā yabqā fīyya rabbāniyyatun li-ghayrika / Wa ḥattā aṣluḥa li-ḥaḍratika / Wa akūn min ahl khuṣūṣiyyatika / Mustamsikan bi-adabihi wa sunnatihi / yā Allāh, yā Nūr, yā Ḥaqq, yā Amīn / Ṣallā-lāh ‘alayhi wa ālihi wa aṣḥābihi wa ahl baytihi ajma’īn.

My God, by virtue of the rank and dignity of Thy Prophet, closest to Thee, our master Muhammad / And of Thy love for him and his love for Thee / And by virtue of the secret that subsists between Thee and him / I ask Thee to send blessings and peace upon him / As well as to his family and his Companions / (And I ask Thee) My God, to increase / My love for him, and to make me know / His reality and his rank / That Thou might grant it to me to imitate him / And follow his conduct and his sunna / Reunite me with him and grant me the joy of a vision of him / Overwhelm me with the happiness of speaking with him / Remove from me the obstacles, the attachments, the intermediaries and the veil / And charm my ear with the pleasure of hearing his words / Prepare me to learn from him, make me worthy to serve him / Let my prayer upon him / Be a brilliant light, perfect and perfecting, pure and purifying / Erasing all injustice and darkness / All doubt, associationism and impiety, falseness and sin / And let it be the cause of purification / And of elevation, that I might thus attain the supreme station of sincerity and election / Such that no other dominion remains in me but Thine / That I might be made ready for Thy presence / And that I might be among Thine elite / Attached to the [Prophet's] conduct and Thy sunna / O my God, O light, O Evident One / And may divine grace and salvation / Be upon our master Muhammad, his spiritual heirs, his companions, and his family.

In this way the prayers for the Prophet encourage believers to ask for divine blessings for these “men of God,” and not exclusively for his biological descendants. Here, as I described earlier, we can see clearly what is at stake for Sufis in the devotional literature and rituals relating to the cult of the Prophet: Muhammad's heritage, its transmission, and the authority it confers. Sufis are the people whom the Prophet teaches as a master teaches his disciple, and the recitation of the taṣliya becomes a way of attaching oneself to the Prophet as a disciple is attached to his master (“Prepare me to learn from him, make me worthy to serve him”). It is a way of transmitting an esoteric knowledge of the Prophet directly to the disciple during visions of the Prophet, whether sleeping, wakeful, or in an in-between state (“grant me the joy of a vision of him / Overwhelm me with the happiness of speaking with him”).Footnote 66

The Perfect Followers of the Prophet

In Muslim hagiology the vision of the Prophet has gained importance gradually over a long period; shifts of this concept are observable in hagiographical literature and in treatises on sufi doctrine.Footnote 67 One of these pivotal times is the 15th century, when the waking vision of the Prophet becomes an accepted reality in the circles of Egyptian sufi scholars, the specific implications of this being that there are degrees in the perception of the Prophet's presence, the highest of which, reserved for the category of the elect, is that of actually seeing him in the world of the senses, and being guided and inspired by him there. The writings of the Egyptian sufi ‘Abd al-Wahhab al-Shaʿrani (d. 1565) show this shift from the vision as a sign of Prophetic heritage to the vision as a mode of initiation and spiritual transmission directly from the Prophet. In his Kitab Lawaqih al-Anwar al-Qudsiyya (The Fecundating Sacred Illuminations), a textbook on sufi ethics, Shaʿrani writes, “Know that the true master (al-shaykh al-ḥaqīqī) is the Prophet.” He informs us that his masters Nur al-din al-Shuni, Ahmad al-Zawawi, ‘Ali al-Khawwas, and Muhammad al-Manzalawi all practiced the prayer on the Prophet to the point that they were initiated by the Prophet himself (yākhudhuna ‘anhu), and that he educated them directly, without intermediary (wasīṭa). Shaʿrani was given the following account by his master Ahmad al-Zawawi:

Our path consists of the assiduous recitation of the taṣliya until the Prophet is by our side even when we are awake, and we become companions just like the Companions, and we are able to ask him about religious questions and about the hadith that our scholars have declared to be weak, this so that we may work according to his word; for as long as this does not come about, it will be because we are not among those who practise the taṣliya assiduously.Footnote 68

I mentioned earlier that, beginning in 1491, Nur al-din al-Shuni instituted the majlis ṣalat ‘alā al-nabī at al-Azhar, a whole night of prayers devoted to the Prophet, a practice that was attacked by certain fuqahā’. For Shaʿrani, who is probably the most widely disseminated sufi writer from the 16th to the 19th century, the waking vision of the prophet gives the saint the rank of jurist (mujtahid). Relying on a metaphysical principle derived from Ibn ‘Arabi, he underlined the superiority of the mystical inspiration of the sufi, who receives knowledge of legal judgments in its fullness by means of unveiling (kashf), while in a waking vision, directly from the Prophet. His idea that the mystic should have direct access to the source of the law (‘ayn al-sharī‘a) is theorized in his textbook, al-Mizan al-Kubra (The Universal Balance).Footnote 69 Shaʿrani confirms, in the biographical note dedicated to his teacher al-Suyuti that appears in his Tabaqat al-Sughra (The Minor Book of the Generations), that al-Suyuti did lay some claim to the status of absolute mujtahid (mujtahid muṭlaq); he follows this information with a discussion of al-Suyuti's miraculous waking visions of the Prophet.Footnote 70 Al-Suyuti also claimed another title closely linked with mujtahid status, that of mujaddid (renewer of religion) of the 15th century (in accordance with the hadith “Indeed God will send to this community (umma) at the beginning/end (ra's) of every hundred years one who will renew (yujaddid) for it its religion.” But the concept of tajdīd is defined in the doctrine of sufi jurists as “the uninterrupted process of revelation through infinite spiritual interpretation of the scriptures.”Footnote 71 It relates closely to the doctrine of sainthood (walāya) and to the messianic figure of the renewer, which can be identical with the Qutb, the supreme pole and head of the hierarchy of saints.

The method of spiritual realization through direct encounter with the Prophet would become formalized in the scholarly circles of Medina during the 17th century and take the name of “Muhammadan path” (ṭarīqa Muḥammadiyya). Hasan al-‘Ujaymi (d. 1702), who received this path from his master Ahmad al-Qushshashi (d. 1661) through a chain of transmission (isnad) that connects to Ahmad al-Shinnawi (d. 1619), Sha‘rani, ‘Ali al-Khawwas, and the Prophet, wrote down a definition passed on by the Moroccan sufi Abu Salim al-‘Ayyashi (d. 1679), who was part of the intellectual circles of Medina during his stay in the Holy City:

Be with the Prophet like the disciple with his shaykh, you must fill your heart with an absolute love for him until you can see him present before you with the eyes of your interior vision (timthālihi bayna ‘aynay baṣīratika). . . . And if you persevere in the reciting of the prayer on the Prophet, God will cover you with graces and the pupil of your inner vision (sawād baṣīratika) will become the throne of divine manifestations and the receptacle of his agency on earth (khilāfa).Footnote 72

The reason for the return of this theme of the tajdīd in the modern period is that the Prophet became the master of numerous sufis who were renewing old paths or founding new ones: the Indian Ahmad Sirhindi (d. 1624), the Damascene Mustafa al-Bakri (d. 1749), the Medinese Muhammad al-Samman (d. 1775), the Maghrebi Ahmad al-Tijani (d. 1815). All of these masters claimed the same status in the order of sainthood as that of the Prophet within his community. Their brotherhoods played major religious, social, and political roles from the 18th to the 20th centuries amid European colonialism.

Prophetic Piety, Mysticism, and Politics in the Early Modern Period

This shift in the concept of sainthood underlines the temporal authority and probably unprecedented public role of sufis at the dawn of the modern era.Footnote 73 This authority rested on their reputation for sanctity, their exoteric knowledge, the economic and social functions of their institutions (tekkes, zawiyas), and their position as intermediary between political leaders and those they governed. From Morocco to central Asia, sufi brotherhoods underwent a new expansion because of the waves of immigration and the mobility brought about by military conquest. Their wider presence geographically was accompanied by an increased influence at all levels of society, starting with the sultans themselves, for whom they were political counselors.Footnote 74 Sufis who made predictions (firāsa) and provided spiritual support (madad) for rulers were the most significant authors of mirror for princes (naṣīḥatnāme) texts. Derin Terzioğlu observes that although theories of “the esoteric government” (dawla bāṭiniyya, dīwān al-awliyāʾ) derived from the concept of sainthood (walāya) as governorship (wilāya) developed across the Muslim world starting in the 14th century, they appeared in Ottoman political literature from the beginning of the 16th century.Footnote 75 The mystical doctrine of the presence of the Prophet, the possibility of seeing him and uniting with him to become oneself a manifestation of the tangible presence of the Prophet's mystical body, resonated strongly with the sultans who appropriated it for reasons of political legitimization and religious conviction. The sufi-prince pairing was an incontestable fact at the beginning of the modern era; there was a mirroring effect, a correspondence in operation between sufis and sultans that has been well-demonstrated by Alexandre Papas in the master-disciple relations between Shaybanid sultans and Naqshbandi masters in 16th-century central Asia.Footnote 76 In Morocco during the same period, the birth of the Sharifian state, in the context of the reconquest of Christian-occupied territories, gave a new social, political, and cultural importance to the Prophet and his descendants, among whom the sacred lineages of the great zawiyas, as well as the sultan, counted themselves. The Saʿadi sultans (r. 1549–1659) provided themselves with a descent from the Prophet, and Ahmad al-Mansur (r. 1578–1603) used this legitimacy to justify giving himself the title of universal caliph.Footnote 77 The rise of the Saʿadis was closely linked with that of Jazulism, the most important mystical movement in Morocco in the 15th and 16th centuries.Footnote 78 The writings of Muhammad al-Jazuli, the author of the Dala'il al-Khayrat, with their eschatological bent based on the notion of saʿda (the promise of happiness here below and in the afterlife), provided the ideological foundation for the legitimization of the Saʿadis and were exploited to this end by the sultans. In Iran a sufi brotherhood, the Safawiyya, took power and created an empire, that of the Safavids, on the basis of the millenarian predication of its mystical and charismatic sovereign, Ismaʿil Shah (r. 1501–24). He claimed a doubly sacred descent from the Prophet and from his cousin and son-in-law, ‘Ali, and a quasi-divine status as well-guided imam and Mahdi.Footnote 79 His charisma was reinforced by a series of victories against the Ottomans, which the latter brought to a definitive end at Chaldiran in 1514. This victory and that over the Mamluk empire that followed it in 1516 were events that would leave a profound and lasting impression on the religious policies of the Ottomans. Not being Arabs or descendants of the Prophet's Qurayshi tribe, the Ottoman sultans had little or no grounds on which to claim the caliphate through heritage. They therefore had to base their claim to it on the superiority of their ties with the Prophet, as his servants and protégés. They likened their own epic to that of the Prophet of Islam, seeing themselves as renewers of his community and appropriating his spiritual and temporal heritage. To reinforce their connection to the Prophet they encouraged the cult of his person by organizing important festivities to commemorate his birth: official celebration of the Prophet's birthday was introduced at the Ottoman court in 1588 by Murad III (r. 1574–95).Footnote 80 The same sultan commissioned a vast Prophetic epic, Siyar-i Nabi, “the most complete visual portrayal of the life of the Prophet Muhammad,” containing a corpus of over eight hundred miniatures.Footnote 81 It is not surprising that Murad III was so closely attentive to the veneration of the Prophet. Özgen Felek offers a fine analysis of this sultan's personality and of the way he fashioned his image and represented himself among his contemporaries and for posterity through Kitabu'l Menamat (The Book of Dreams), a collection of the poems and dreams he regularly communicated to his spiritual master, the Kalwati sufi Suca’ Dede (d. 1587/88). The letters were compiled in 1591, just after the end of the first Muslim millennium. Murad III dispensed with the image of the conquering warrior (ghāzī), so appropriate for a sultan, to put on the habit of a mystic; the Kitabu'l Menamat describes his spiritual progression as far as his ascension to the most elevated degree of the quṭbiyya, that of pole of poles (kuṭbul-akṭāb); he is enthroned in a dream by an assembly of all the saints.Footnote 82

Like their subjects, the sultans pledged allegiance to the Prophet and put themselves under his protection. Gottfried Hagen argues that this cult of the Prophet under the auspices of the House of Osman was part of a specific configuration of Islamic religiosity centered on the persona of the Prophet, one that was informed by narratives (sīra nabawiyya, praise poetry, ḥilye, mawlid) and rituals (carrying, displaying, and visiting the Prophet's relics, such as his mantle and his banner) rather than being theorized in theological writing. This configuration emphasized charisma, performance, and emotional expressivity. It invoked the presence of the Prophet rather than his historical figure, and promised to lead believers to salvation by means of spiritual immersion rather than by imitative orthopraxy.Footnote 83

Conclusion

As with the hagiographies of the saints, another genre that has been neglected in academic research, devotional literature provides essential insights into piety and religious expression among Muslims in the premodern era. Here the hope for salvation is expressed less through strict application of the shariʿa, which is an ideal sought but hard to accomplish, than through the exclusive relationship with the Prophet and his heirs that this literature nourishes. In addition to fulfilling a ritual function, devotional literature diffuses theological and metaphysical teachings on the Prophet's status that were elaborated by sufis and became part of popular belief: he is the perfect man (insān kāmil) made in God's image, and the cause of all creation. After Muhammad's death, this perfection is transmitted to his heirs, the saints (awliyā’ Allah, friends of God), via the path that is eventually formalized under the name of Muhammadan path. Indeed, sufis consider the saints to be the true heirs of the Prophet, the religious scholars and spiritual guides of Muhammad's own community, as in the hadith: “The ʿulama’ are the heirs of the prophets” (al-‘ulamā’ warathatu al-anbiyā’).

Devotional beliefs and practices around the figure of the Prophet do not necessarily change in parallel with the rapidly shifting events of political history. The cult of the Prophet was built over time, and it obeys a complex dynamic of its own, although it does increase in importance during political crises, a sort of compensatory effect, reflecting a need for legitimization of the spiritual heirs of the Prophet, as well as his descendants (ashrāf/shurafā’). Starting in the 12th century the production of devotional texts increased continuously. The religious policies of the Ottomans were based on a medieval heritage that reached its apogee in the 15th century, when Maghrebi and Egyptian Sufi scholars had a marked influence. Conquest and the subsequent development of commercial routes made the circulation of goods and people easier, and allowed the diffusion of a large number of devotional texts, some of which, such as al-Jazuli's Dala'il al-Khayrat, acquired quasi-international fame.

Collections of prayers on the Prophet all share a similar structure, with introductory chapters on the benefits and merits of prayer on the Prophet (drawing on the Qur'an and hadiths), and a section dedicated to the description of the Prophet's physical and spiritual qualities (shamā’il), his special attributes (ṣifāt, khaṣā’iṣ), his miracles (mu‘jizāt; for example, the miracle of the mi‘rāj), and an assemblage of prayers taking up themes from the Sira, the hadiths, and the mawlidiyyāt. What differentiates collections appearing from the 15th century onward, and makes them novel, is the organization of the prayers according to a Qur'anic model; as with Qur'anic recitation, such prayers were intended to be read aloud on a regular basis, and, like the Qur'an, they inspired the development of professional reciters (qurrā’) paid by the charitable endowments of the mosques in which they were employed. In this respect the Wahhabis were not mistaken: collections such as the Dala'il did acquire a sacred status.

This article began with a reference to Ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab's destruction by auto da fé of the Dala'il during the 18th century. The event was certainly noticed at the time, but it was the beginning of the 20th century that saw the gradual diffusion and circulation of Wahhabi ideas inspired by Ibn Taymiyya (d. 1328), who believed that the Prophet was definitely dead and thus incapable of offering aid or even intercession at any point during the interlude preceding the end of the world. The devotional texts that circulated during the Ottoman period would be among the first lithographically printed books to be distributed in the 19th century. Detailed studies undertaken in the libraries of Morocco and Egypt have demonstrated that traditional mawlid narratives took pride of place throughout the 19th century, along with an extensive literature exalting devotion to the Prophet, his family, and the saints, often in the form of small inexpensive volumes or pamphlets.Footnote 84 The Ottoman Turkish translation of the Sira Halabiyya was printed in Bulaq in Egypt as early as 1833 (whereas the Arabic text was not produced in print, in three volumes, until 1875). In its margins the 1833 edition contains a Sira by Ahmad Zayni Dahlan (d. 1886), the Shafi‘i mufti of Mecca, al-Sira al-Nabawiyya wa al-Athar al-Muhammadiyya (The Life and the Noble Traces of the Prophet).Footnote 85 The Burda was printed in Bulaq in 1844 and in a Cairene private printing house in 1863. The Dalaʾil al-Khayrat was published in lithographic form in 1840, and the commentary by Muhammad al-Mahdi al-Fasi as early as 1865. Finally, we must not forget the monumental devotional work on the Prophet that was printed between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th: Jawahir al-Bihar fi Fada'il al-Nabi al-Mukhtar (Pearls from the Oceans of Virtues of the Chosen Prophet), and al-Majmu'a al-Nabhaniyya fi'l-Mada'ih al-Nabawiyya (Nabhani's Compilation of Praise Poetry Dedicated to the Prophet) by the Syrian Yusuf al-Nabhani (d. 1932), two anthologies of prose and verse honoring the Prophet, mostly dating from the Mamluk or Ottoman periods. The collected authors write in Arabic but are not necessarily Arabs.Footnote 86 The writings of Yusuf Nabhani himself also are representative of this period: he was a panegyrist who had trained at al-Azhar, deeply influenced by al-Qastallani's Al-Mawahib al-Laduniyya, and who wanted, in times that were marked by the beginnings of Islamic reformism, to preserve a centuries-long literary tradition (which he probably felt was threatened) by bringing it together and rewriting it for a broad audience.