In August 1966, President al-Habib Bourguiba addressed the nation to celebrate Women's Day and commemorate the tenth anniversary of the promulgation of Tunisia's personal status code. Positioning himself as a wise, experienced, and valued counselor, he emphasized the code's pivotal role in facilitating women's contribution to national development and detailed the improvements to women's condition over the previous decade. Emphasizing the importance of marriage and childbearing for the rejuvenation of the nation and its progress, he cautioned his audience to exercise discipline and moral restraint lest women's excessive liberties lead to moral crisis and disintegration of the family. The country's dignity and evolution were maintained and threatened by both male and female behaviors, with familial collapse associated with particular types and styles: seducers, libertines, disheveled bachelors at dance clubs who wore “their hair long, like beatniks,” and women who dressed provocatively in “slavish imitation of certain foreign customs.” Bourguiba particularly singled out the miniskirt as dangerous and ridiculous because it revealed women's thighs and “allow[ed] the female body to disclose its secrets,” whereas “a full dress or pleated skirt” would earn “the confidence of the man who wants to found a family with her and lead a harmonious life.”Footnote 1 In these terms, Bourguiba juxtaposed local values and sanctity of the family with “lascivious” short skirts and “debased” nightlife associated with “beatnik” styles and pernicious American or Western counterculture influences. “Proper” dress came to signify respectability, national identity, generational difference, acceptable gender roles, and a desire to preserve social norms in a changing world.

The idiom of dress concretized the abstract concepts of ethical conduct and concern for the nuclear family common to presidential speeches, but in a way that spoke to the gendered and generational anxieties about youth notable in the 1960s. In Tunisia's urban areas in particular, an expanding education system contributed to the rise in the average age of marriage, which was often considered an entry point to adulthood.Footnote 2 Although university students were a dynamic force cherished by the regime as representing the newly independent nation, dissent on campus raised concerns about the autonomy of young men. These contradictions were part of the widespread recognition of adolescence as a distinct phase in life, and its association with rebellion thanks to more recent youthful involvement in anticolonial nationalism, pan-Arabism, and Third World radicalism. Concerns about whether to educate or discipline the younger generation reflected the popularization of psychology and beliefs about delinquency that Omnia El Shakry and Sara Pursley have identified in Egypt and Iraq.Footnote 3 In the context of transnational political movements of the 1960s, certain styles became symbolic of unruly youthful subjectivities and a questionable devotion to the nation. Blending its patriarchal and liberal dispositions, the Tunisian state depicted youth as a preadult phase that excluded those passing through it from participation in politics.Footnote 4

By determining the boundaries of proper appearance, Tunisia's ruling party strove to control both women and men. Not entirely distinct from the veil, and the well-documented preoccupation with its meaning among colonizers, feminists, nationalists, and reformers across the Middle East, the hats, suits, and skirts that constituted modern dress were visible markers of identity with malleable political symbolism. An oft-recited story holds that Bourguiba criticized women's unveiling in the 1930s as acquiescence to French colonial policy and a betrayal of national identity. After independence, he encouraged the removal of the safsārī (a long piece of fabric covering the woman's body and hair and often pulled across the face), which he derided as a relic of tradition. Both positions index Bourguiba's desire to subordinate the nascent women's movement and harness it to his personal political program.Footnote 5 Relegating certain styles to the national past, and delegitimizing others as foreign, his postcolonial rhetoric about dress sought to regulate interactions between men and women in an increasingly heterosocial, middle-class, and urban public sphere. The visual homogeneity of men in sober suits, and women in sweaters, skirts, and heels, demonstrated the bourgeois nature of Tunisian modernity and its silencing of class struggle. Falling anywhere from slightly above the top of the knee to part way up the thigh, the miniskirt was an erotic commodity that revealed extended portions of the female body, transcending the boundaries of propriety by suggesting women's autonomy and sexual liberation. As such, it was a catalyst for fears about gender roles, youth culture, the nuclear family, women's employment, and public space.

This article draws on conversations about fashion from Tunisian periodicals that I see as illustrative of public opinion amongst middle-class readers, including the international weekly Jeune Afrique (Young Africa), the women's magazine Faiza, and to a lesser extent the nationalist al-Marʾa and Femme (Woman).Footnote 6 Both Jeune Afrique and Faiza created a space for interacting with readers by printing their letters, conducting surveys, and soliciting input. The publications had limited circulation given low literacy rates. Predominantly in French, they reflected the educational proclivities of an older generation and its approach to national culture. This audience was emblematic of the nation's modern image and disproportionately influential in political matters. Under the protective cover of the relatively inoffensive matter of dress, the press provided a forum for middle-class women and men—many of whom embraced secular feminism—to scrutinize the hegemonic construction of womanhood, national identity, and masculinity.

The first section of this article offers historical context on how a young generation was brought into the orbit of the single-party state through public sector employment and affiliation with the ruling party and its satellite organizations. The bourgeois elements of national culture stemmed from such courting of an urban middle class to fortify the party's base and further distance it from economically and politically marginalized rural communities and the working class. The second section examines presidential speeches and ministerial publications as representative of hegemonic state feminism. I argue that official ideology depicted clothing as a visual signifier of the nation's modernity that could be measured through its progressive distance from rural traditions, belying the tendency towards control characteristic of the ruling party's conservative patriarchy. Relying largely on women's magazines, the third section explores how the ostensibly frivolous topic of dress allowed women to articulate understandings of modesty in both moral and economic terms, proposing that shopping was an act of patriotic devotion. Turning to men, the final section builds upon the insight of Aziz Krichen, Nouri Gana, and Robert Lang that Bourguiba's patriarchal impulses perverted the options for manhood and masculinity among urban educated sectors of the population as he became the focal point in political life and nationalist genealogies.Footnote 7 Despite the widespread adoption of suits among nationalist cadres, Bourguiba's attempt to render men's clothing choices threats to national sovereignty did not resonate. Instead, I suggest that his scrutiny of men's behavior opened the door for a conversation about masculinity and gender roles. Young women urged their male peers to acknowledge how male privilege impeded the full realization of women's liberation. The single-party state's disavowal of trendy miniskirts and long hairstyles did more than promote an aesthetic of national unity; it revealed the tenuous nature of its bourgeois consensus. Though lacking the ability to challenge state patriarchy and operating within the constraints of an authoritarian political context, including the press, debates about fashion reveal an intraelite struggle against the ideological and practical limits of secular feminism.

DECOLONIZATION, NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT, AND TUNISIA'S SECULAR MODERNITY

One of the most conspicuous trends in postindependence Tunisia's nation building was the commitment to state feminism inaugurated by the 1956 personal status code. Raising the minimum age of marriage, abolishing polygamy, converting divorce into a civil procedure, and placing matters of custody and inheritance within the purview of a centralized legal system, this law was the hallmark of Tunisia's secular image; justified in terms of Islamic jurisprudence, it weakened religious authority in favor of the president. This project of legal and social reform dovetailed with the nominally socialist turn signaled by the renaming of the ruling party as the Dustur Socialist Party (Hizb al-Ishtiraki al-Dusturi), a stage that lasted until 1969, leading one scholar to characterize the 1960s as an era when the “political elite's will to transform society was at its height.”Footnote 8 However, the state's official embrace of certain feminist policies facilitated authoritarian centralization and the exigencies of postindependence economic development. New labor legislation brought women into a workforce full of gaps left by departing colonists, though mainly as low-paid factory workers and secretaries. Bourguiba's authority was neither unchallenged nor secure, as demonstrated by the tenacity with which he repressed political opponents, dismissed the “cultural traditions” of the rural interior, and exaggerated a communist threat. Women proved to be an important resource for bolstering the fragile middle-class base of the young nation.

Women who were close relatives of Bourguiba or the wives of high-ranking male party figures were granted prominent positions in the National Union of Tunisian Women (Union Nationale de la Femme Tunisienne; UNFT).Footnote 9 Founded in 1956 by Bourguiba's Dustur party, it was the primary vehicle for translating official policy related to women into local practices such as holding public forums to explain the personal status code. Under the UNFT, women performed the work of numerous state ministries: they provided vocational training for the artisanal sector and rural social workers and sponsored literacy classes, children's clubs, after-school programs, and a women's dormitory at the university. Many women active before independence joined the union because alternate political platforms were discouraged and later banned. During the 1960s, the UNFT remained closely tied to the ruling party. Bourguiba presided over its annual congresses, and UNFT leaders were incorporated into party structures, with access to ministerial meetings and diplomatic visitors, though they were not granted decision-making authority.

Opportunities in education increased for men and women coming of age in the 1960s. The first ten-year plan in 1958 set universal education as its goal, standardized and centralized education, and shifted the language of instruction to Arabic, though French continued to dominate the classroom at the secondary level. The numbers and rate of school enrollment increased for both sexes, with 3,725 students enrolled at the university by 1961, or three times the figure prior to independence. Slightly more students attended the recently opened University of Tunis than universities in France. Numbering approximately 600, female students remained a minority of the university student body. Although the law initiated major strides in ameliorating the abysmal state of women's education under French colonial rule, women's literacy rates only increased from 4 percent in 1956 to 17.6 percent in 1966.Footnote 10

Women gained new opportunities for formal employment but also faced limitations. Women's entry into the salaried workforce was instrumental to meeting postindependence production and consumption demands. The state explicitly encouraged women's professionalization. For example, it built an elite class of salaried women teachers numbering in the thousands by the mid-1960s and employed smaller numbers of women in ministries, primarily as secretaries. Still, the overwhelming majority of working women were agricultural laborers (over 90 percent by some estimates), with additional concentrations in the artisanal sector and domestic service; though women participated in labor unions, they were underrepresented and distanced from positions of authority.Footnote 11 Women with disposable income and access to consumer goods were critical to sustaining nascent state industries as evidenced by advertisements. From luxury goods such as jewelry and lingerie, to mundane commodities such as biscuits and insecticide, advertisements catered to female consumers by depicting modern femininity in relation to material goods and a consumerist domesticity.

A decade of economic growth in Tunisia expanded the ruling class, leaving in place structural inequalities. Investment in building and the tourist sector along the Mediterranean coastline increasingly marginalized the rural interior while the mechanization of agriculture weakened rural subsistence. All of this contributed to unemployment and rural-to-urban migration, and did not mitigate the colonial legacy of concentrated land ownership—approximately 83 percent of farmers owned only 34 percent of the land.Footnote 12 The single-party state sidelined the working class and peasants as it consolidated its power in ways that benefited large landowners and the urban middle classes.Footnote 13 These socio-economic fractures were the basis of the president's rivalry with nationalist Salih bin Yusuf from 1955 onwards. Supported by the commercial class, Bin Yusuf advocated socialist planning, political pluralism, and an autonomous civil society. Bourguiba often reduced these demands to Communism or Arab nationalism, or portrayed them as a conservative resistance to modernization, calling for national unity to weaken and discredit opponents who spoke of inequality in Marxist terms.Footnote 14 After Bin Yusuf's assassination in exile in 1961, many of his partisans remained opposed to Bourguiba's policies and some participated in the heterogeneous and disorganized groups that plotted against the regime and were eventually uncovered in December 1962. With the small Tunisian Communist Party outlawed and the trade union confederation subordinated, the student union provided a rare, but modest, avenue for resistance.

Young men were crucial to the single-party state's national projects. The state actively courted university students, whom Bourguiba addressed as the “hope of the nation,” supporting them through scholarships.Footnote 15 Their incorporation into the ruling party often began with membership in the national student union, which became more concerned with executing Dustur policy than deliberation. Rejecting this subordination, leftist coalitions on university campuses defected from the union and contributed to protests between 1966 and 1968. Organizing in Tunis, Paris, and Cairo, students voiced their demands for economic and political change using anti-imperialist socialist rhetoric.Footnote 16 Instead of solidifying the party's middle-class base, their references to class struggle threatened the notion of national unity. The regime read students’ fluency in worldwide cultural currents as synonymous with antiestablishment ideologies that it derided as evidence of a foreign conspiracy. Considering the incomplete nature of Bourguiba's control over national politics, recently enfranchised women formed an important component of the Dustur party's middle-class base. Yet indications of women's sexual liberation and student autonomy violated expectations of filial obedience to presidential authority. The fashion trends adopted by young men and women came to be associated with threats to the ruling establishment's class base and to serve as a reminder of its fragile hold on power.

STATE FEMINISM AND THE VISIBILITY OF THE MODERN WOMAN

Turkey and Iran in the 1920s and 1930s, and Egypt and Tunisia in the 1950s, adopted secular feminist platforms to signal modernity and independence. By regulating marriage, divorce, and employment, they extended state power over their citizens with particular bodily ramifications for how individuals operated and interacted in public spaces and at home. State-led legal and policy changes were often accompanied by at least modest investments in national education, disproportionately benefitting middle-class and urban women. Mervat Hatem points out that such opportunities were not without ramifications as women now relied on the state, which replaced intimate familial forms of male control with public patriarchy.Footnote 17 These regimes shared the perception that veiling was anathema to the imagery of modern womanhood, and the secular state's prerogative to liberate them.Footnote 18 As Camron Amin has noted, under Iran's Pahlavi monarchy, “Women's bodies needed to be unveiled so that the regime could display and celebrate the progress of women . . . progress it initiated, progress it co-opted, and . . . progress it controlled.”Footnote 19 Minoo Moallem elaborates that clothing became part of nationalist discursive practices to “commemorate specific bodies—through gendered and heterosexist practices, gestures, and postures—serving not only to facilitate modern disciplinary control of the body but also to create gendered citizenship.”Footnote 20

Despite the Tunisian regime's unique combination of secularism, nominal democracy, and a liberal anti-Communist orientation, it shared many commonalities with other states in the region in terms of state feminism, as observed by scholars attentive to distinguishing Tunisian state feminism from gender equality. For instance, Laurie Brand has shown how Bourguiba did not seek to “undermine traditional family relations,” and neither did the UNFT, making the women's organization complicit in a statist agenda to preserve male privilege.Footnote 21 Tunisian feminist sociologist Ilhem Marzouki has further argued that the instrumentalization of women's rights and the subordination of the UNFT left women powerless and trapped “between public declarations and favorable legislative measures and the effective absence from decision-making.”Footnote 22 Others have used discursive analysis to deconstruct the idea of the “Tunisian woman” and how such rhetoric contributed to women's subordination, and have insisted that authoritarianism is as much to blame as patriarchy for women's (and men's) lack of autonomy.Footnote 23 This section considers modern dress as an important site for the articulation of feminist mantras, but one that the state failed to control. On the one hand, as a visual testament of progress clothing provided the means to solidify the ruling party's regional and class base around a modernizing project. On the other hand, the tone of moral panic in presidential speeches of the 1960s, as the regime latched on to women's dress, exposed the state's inability to define the meaning of liberation—and delineate gender roles.

Celebrated as a hero of the anticolonial nationalist movement, Bourguiba played an outsized role in national politics and associational life.Footnote 24 He communicated policy stances through public oration on nation-wide tours, at regional party meetings, and during congresses of state-sanctified associations—speeches that were broadcast on the radio and detailed in the press. Individual speeches were reproduced in booklets and collected into annual volumes, and many were translated into English and French. Given frequent ministerial rearrangements and the increasing monopoly of the Dustur party on state and civil society, presidential discourse powerfully shaped the international image of the Tunisian state. References to women in these texts suggest an overlap between domestic and international interests. On the one hand stood the imperative of the party–state alliance with middle-class women, and on the other hand an awareness of how women's visibility in urban public spaces continued to attest to a nation's progress. The speeches idealized urban middle-class practices as models of acceptable modern womanhood, women's emancipation, and gender roles.

The circumscribed nature of women's liberation and its sartorial codes were present from the announcement of the personal status code in 1956; discourses sanctifying this event as “the lifting of the veil, and the emancipation of women,” merged the visibility of women with the personal status laws.Footnote 25 This connection was popularized by the UNFT as the official mechanism for communicating the message about women's rights, as it encouraged women to unveil and projected urban values into the rural interior.Footnote 26 In fact, Bourguiba even gauged the contributions of the union towards national progress through “the delegates’ apparel,” which over the years since independence had become “much more modern.”Footnote 27

Women's public presence established a set of morals and the temporal terms of the young nation's distance from an oppressive past of ignorance and gender segregation; polygamy was an “old tradition” that Bourguiba abolished in favor of a law with a more “modern character.”Footnote 28 State publications noted how “the streets are enlivened by pretty little faces,” equating women's unveiled public presence with their recently acquired freedom.Footnote 29 Women's unveiled bodies also signaled national prosperity, with one text prophesizing: “Once the living standard has risen . . . there will no longer be any economic reason for the veil [sefseri], which will die a natural death and with it the seclusion of women will come to an end.”Footnote 30 The story of women's transformation—“Yesterday a slave, today a citizen”—was told in numerous official publications through images of women wearing long, draping mālāya (sing. maliya; a common article of clothing that extended past the knees and was often cinched with a belt), their heads covered and their feet bare, juxtaposed with schoolgirls wearing bright white uniforms and sitting in evenly spaced rows. In reality, Tunisian women's sartorial choices could not be neatly separated into modern-urban versus traditional-rural as attested by photographs of women in safāsir (sing. safsārī) at a polling station. Yet by contrasting cleanliness and trim lines with loose-fitting and colorful rural attire, images of women in lab coats and tailored blazers indexed the nation's rational progress and collective modernity.

Patriarchal fears of women's autonomy were informed by its sexual implications. The UNFT conveyed to women their responsibility to practice “self-control during this dangerous transition from a passive state to a free, active life,” and to assuage fears that “sudden emancipation would lead to moral license and debauchery.”Footnote 31 The fragile balance between granting rights and imposing control was further destabilized by the 1961 legalization of contraceptives and, in the following years, the nationwide provision of family planning services.Footnote 32 In line with the civilizing and developmentalist perspective of the international population control movement, the Tunisian state presented family size and contraceptive practices along modernity–tradition and urban–rural continuums, locating large families and “disorderly” population growth among bedouin communities in the rural interior. The official logo for family planning included a silhouette of a modern couple with two children, identifiable as a nuclear family, that was detailed enough to reveal the wife's knee-length, A-line skirt (though many of the recipients of family-planning services shown in brochures were women in colorful mālāya or safāsir seated on the ground and surrounded by children). The president worried that emancipated women who displayed “excessive independence towards their husbands” could potentially “drive the country . . . towards licentiousness and the dissolution of morals.”Footnote 33 Though rational and modern, increased access to reproductive technologies and the ability to exercise bodily control made individual women potential sources of national threat.

Bourguiba's was not the only voice navigating the meaning of emancipation, its impact on gender roles, and the morality of birth control. The question of whether the purported economic imperative of small families outweighed ethical concerns about women's sexuality and family life attributed to contraception was raised by the weekly news magazine Jeune Afrique, whose director Béchir Ben Yahmed (al-Bashir bin Yahmad) briefly served as secretary of state in Bourguiba's cabinet and after stepping down continued to closely observe Tunisian politics.Footnote 34 A cover story highlighting concerns about contraceptives asked: “Is birth-control an antidote to underdevelopment? Is it morally reprehensible? Whose morals?” The issue featured the views of two middle-aged male deputies, Othmane ben Aleya (ʿUthman bin ʿAliya), a single lawyer, and Lamine Chabbi (al-Amin al-Shabi), a father of six. Ben Aleya argued for the necessity of contraception given the costs of state welfare programs, education, and healthcare. He dismissed claims that contraception would lead to loose morals. Chabbi, in contrast, was against permitting the sale of contraceptives because he feared that women would abuse the “antichildren” pills, instead of making the noble sacrifice for the cause of motherhood.Footnote 35 Readers were divided between accepting birth control as the “lesser evil” and worrying about imminent moral disasters produced by its availability: “Does the use of contraception risk leading to the abandoning of morals by our youth? I firmly believe it does,” stated Mrs. Belaya.Footnote 36

In its publications, the UNFT brought the cautionary tone about liberation (and morals) back to the question of appearance, where women's honor could be sullied by supposedly foreign icons of false liberation.Footnote 37 An editorial in Femme scoffed at the notion that “the miniskirt and outrageous makeup are really essential for women to be considered liberated and emancipated,” deriding such fashions as a form of cultural alienation.Footnote 38 UNFT president Radhia Haddad (Radiya al-Haddad) clarified that the critique of makeup and anti-mini stance in Bourguiba's August 1966 speech did not contradict women's evolution but “were only intended to preserve morals.”Footnote 39 Reflecting on these experiences in her memoirs, Haddad noted, “the women's union led a permanent campaign to contain women's thirst for freedom within reasonable limits.” Though she found veiling an obstacle to public engagement, she wavered between practical and symbolic assessments of clothing:

I was no less shocked by how certain women blindly followed certain western clothing styles. The miniskirt for instance caused many negative reactions and the rejection of women's emancipation. Like other women, I like fashion and its caprices, but I never hesitated when it was a question of choosing between decency and fashion.Footnote 40

Haddad's feminism incorporated the liberal critique of the veil as a physical barrier to women's activities while connecting outward appearance to inner morals. The miniskirt marked the threshold between proper women's emancipation and “indecency.”

Presidential statements and official publications targeted different audiences but indicate domestic attention to the international context and shared perceptions about modernity. As they reverberated across the public domain, these texts insisted that as representatives of the nation, women should preserve a cultural specificity defined less by romanticizing a folkloric tradition than by modern urban practices that evidenced its moral standards. Without physical veils, liberated women required a “veiling of conduct,” similar to the behavioral norms expected of Egyptian women in coed workplaces in the same era.Footnote 41 The nuclear household and the reproduction of small families were nationalist ideals, sartorially represented, or transgressed, by skirt lengths.

“GOOD SENSE, MORALS, OR SNOBBISHNESS”: DEBATING FASHION AND WOMANHOOD

As Jeune Afrique playfully pointed out, miniskirts were banned in Greece and Senegal. If Brazzaville was the sole African capital allowing the mini by 1968, the journal quipped, it was only authorized for women under age six.Footnote 42 Similar controversies swirled around multiple facets of youthful fashions from clothing and makeup to hair. In Argentina the blue jeans trend sparked discussions about masculinity, desire, and the eroticization of public life, which intersected with class and ideological conflicts.Footnote 43 The Tanzanian regime outlawed miniskirts, wigs, and skin-lightening products in 1969 as antithetical to the national culture of its modern socialist state. But press coverage of fashion in Dar es Salaam reflected concern with rural-to-urban migration and generational differences rather than a consensus distinguishing modern dress from “foreign” fashion.Footnote 44 Even in the US, boys who grew their hair past their ears violated dress codes and provoked heated disputes that led to a series of high-level court cases transforming public schools into “battlegrounds for hotly contested political and cultural issues.”Footnote 45 Across the globe, experimentation in style catalyzed public debates about national identity, foreign cultures, and social disorder, in a politicization of daily life that contributed to the worldwide protests of 1968.Footnote 46 Questions about propriety, perceptions of generational differences, and concerns about national identity, resonated across disparate geographical contexts, enshrining clothing as a recognizable facet of 1960s youth culture. While we know that the Middle East (and the Algerian revolution in particular) served as an inspiration for 1960s political mobilization, we know less about quotidian intellectual and cultural exchanges in the region during this period. Examining Tunisia's francophone press of the era fills this lacuna by providing insight on how middle-class polemics about skirts evoked a cultural repertoire of Beatles music, Italian fashion, and Egyptian films, while remaining deeply mired in local concerns about economic development and postindependence gender roles. The miniskirt was a device for nationalist women to reject foreign cultural influences, immoral behavior, and youthful insurrection, indicative of their adherence to bourgeois norms, while avoiding complete subordination to the hegemonic contours of state feminism.

The 1956 family law and the establishment of the women's union undermined the potential independence of the Tunisian women's movement and sapped its momentum by yoking women's interest to the president. Yet, on the women's pages of newspapers and in literary magazines, deliberations continued about the meaning of women's place in the nation. Short stories by women writers such as Hind ʿAzuz, and Najiyya Thamir were serialized in the Arabic press, with narratives addressing companionate marriage, urban migration, and education that featured female protagonists as agents of modernization.Footnote 47 Seeking to address women readers, the UNFT published its Arabic and French periodicals al-Marʾa and Femme, in 1961 and 1964 respectively. Al-Marʾa was primarily a monthly newsletter focused on the activities of the women's union. Its content encouraged women to preserve their Arab and Islamic identity, maintain moral values, and resist the temptations of “false liberation.” The French edition, which appeared about three times per year, published explanations of state policy emphasizing women's responsibility to the nation supplemented by brief articles on clothing, recipes, and housekeeping.Footnote 48 The colorful and predominantly francophone Faiza (1959–67), alternately a monthly and a bimonthly, addressed Tunisian women through the lens of global sisterhood, reaching a respectable circulation of 15,000 at its peak.Footnote 49 Initially focused on decorative arts and culture under Safia Farhat (Safiyya Farhat), the first woman faculty member at Tunisia's Institute of Fine Arts, it strengthened its nationalist orientation and journalistic quality when Dorra Bouzid (Dura Buzid) joined the editorial committee in 1960, becoming editor-in-chief in 1963 and director in 1965. Its reports addressed political and social matters related to women such as Tunisian legislation, children's health, and education reform. Faiza also followed the development of national theater and cinema, commemorated national holidays, and offered regular updates on Bourguiba's activities. In fact, the educational background, professional success, and francophone cultural orientation of the magazine's editors resonated with Bourguiba's middle-class secular configuration of womanhood.Footnote 50 Though it is possible that Faiza’s editors fabricated letters, they advertised an editorial policy of publishing all correspondence as well as poetry submitted by readers.Footnote 51 Femme, in contrast, printed only a selection of letters where their response allowed for an elaboration of the editors’ pedagogical goals, and replied individually to more personal questions.Footnote 52 Its more sober covers with portraits of the first lady, a provincial girl harvesting oranges, or jewelry donated to the national treasury, reflected its position of responsible citizenship but offered less room for deliberation. This section relies on Faiza to examine middle-class women's engagement with official rhetoric on dress and the relationship between fashion and national identity. While the magazine did not transcend the patriarchal limits of state feminism, it diverged from its moralism by politicizing fashion as a form of economic development and celebration of Tunisian traditions on the runway.

The pages of Faiza employed catchy and attractive images of modern womanhood as attested by cover photos of young carefree women running along the beach, waterskiing, or at the university wearing matching tailored ensembles. Marketing to a readership with disposable income, advertisements helped “define the boundaries of national community,” encouraging readers to recognize sartorial and consumer signs of a bourgeois modernity from well-coiffed women in pleated skirts to electric fans and vacuum cleaners.Footnote 53 For instance, ads for fresh fish and Byrsa tomato paste depicted smiling women with trendy hairstyles, short-sleeved dresses, and clean aprons serving guests or feeding their families. Another ad featured a manicured and seductive woman wearing pearl earrings and a draping blouse enticing readers to smoke El Khadra cigarettes (Figure 1). Although more aspirational than a reflection of Tunisian society, advertising contributed to the magazine's presentation of a visual regime of progress that associated a modern lifestyle with fashionable dress and conspicuous consumption, replicating the basic parameters of official presentations of Tunisian womanhood.

FIGURE 1. An advertisement for Al Khadra cigarettes from Faiza, April 1961.

The association between appearance and a modern persona was described in an exposé on student life that demarcated two student types based on their styles. Girls who were constrained were identifiable through “an empty stare . . . a smile void of charm . . . [and] a particular hairstyle. They generally dress in a manner that lacks taste. They wear colors that do not match. Even their purses are the wrong size for them. As for shoes, they never wear heels.” In contrast, modern liberated girls “dress with discretion and taste,” from their makeup to their “A-line skirts with a sweater and flats.” The first kind of girl was ignorant and the second independent. Constrained girls “do not know how to take advantage of their freedom, the unheard of and unexpected opportunity that their President has given them.” Instead of evolving with the nation, they were restrained by ancestral traditions.Footnote 54 It followed from these categorizations that education did not make a young woman modern. Rather, she needed a middle-class location and the disposable income permitting her to display her awareness of fashion trends in the urban public space of the university.

After Bourguiba's August 1966 declaration that the miniskirt was decadent, or degrading to women in the view of Femme, the state reportedly banned women from wearing short skirts and forced men to cut long hair.Footnote 55 Faiza contributed to public discussions about clothing, as the mini disappeared neither from vitrines nor from public consciousness. Expanding the space in which people could deliberate the meanings of fashion, reporters took to the streets asking Tunisians whether dress choices were “a question of good sense, morals, or snobbishness.” Suʿad, a young trendy woman who appreciated miniskirts, quipped: “If I dress ‘short’ it's not only because that's in style, it's also to keep my youthful freshness. Because wearing short skirts gives you the impression of being a kid.”Footnote 56 Readers disagreed. A letter from three men linked clothing to premarital sex, inappropriate for Tunisian women, and questioned whether they were witnessing “the first signs of decadence in miniskirts and boys with long hair.” They warned youth of both sexes to avoid the vacuity of a “certain European lifestyle,” exhorting their compatriots: “We must remain Tunisians!”Footnote 57 Another reader, Nadiya Kilani, pleaded, “You must guide us, Faiza. On the one hand, there are critiques of the miniskirt, and on the other, you feature them in your fashion pages and continuously promote this style . . . Faiza, you yourself must fight against this crazy trend.”Footnote 58 Such anecdotes suggest the range of values pinned upon a skirt from youthful fun to an immoral and licentious act that threatened the nation.

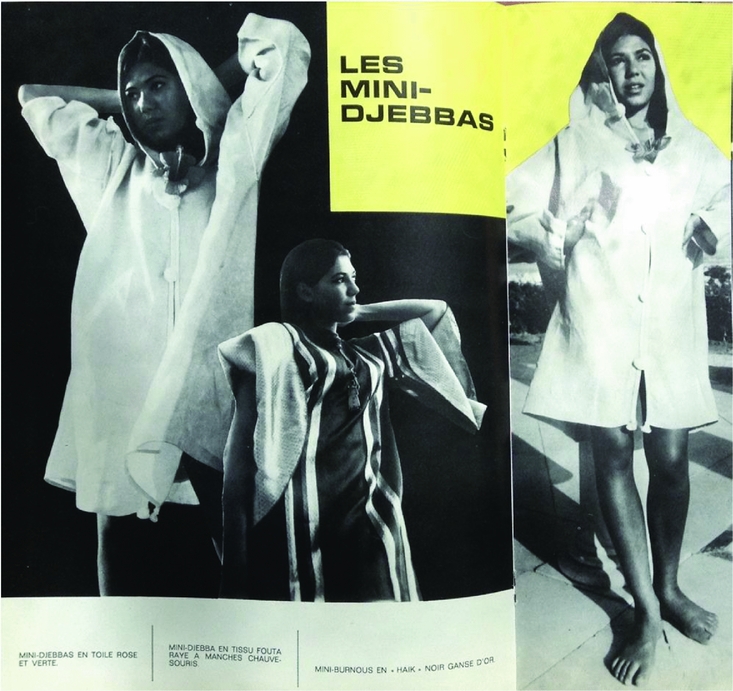

Despite the taboo surrounding the miniskirt, shorter hemlines continued to appear throughout 1966 and 1967 in a number of Faiza’s fashion spreads and covers. Models repeatedly showed their knees and parts of their thighs in an expanding array of minis including the mini-dress and the mini-jubba (Figure 2). Responding to the reader Kilani, the editors justified their position:

The miniskirt! Let's talk about it. We are neither for, nor against it. The mini is perfectly acceptable for the very young (that's what we demonstrated in issue number 60) on whom it is not at all provocative. But of course, it is not recommended for mothers and especially not for those who are overweight. Regardless, this fashion already exists on the streets of Tunis. Why should we bury our heads in the sand and act as if nothing is happening? Even if you cover your eyes and ears, the mini has invaded Tunis. In which case, why not talk about it? That would be a breach of objectivity. That does not mean that we are encouraging it since once again, we only recommend it for the very young.Footnote 59

FIGURE 2. “The mini-jubba and a mini-burnus,” Faiza, August 1967.

Here the editors avoided the issue of morality by depicting the miniskirt as a fait accompli. Their explanation focused on youth and style. Firmly grounded in a position of offering advice on women's matters, the editors presented fashion as a women's domain. Framing the miniskirt as a matter of taste determined by age and body size and “not at all provocative,” they subtly contradicted the garment's association with sexual availability.

Despite efforts to avoid the negative stigma attached to certain fashions, the magazine offered an alternate politicization of clothing by promoting Tunisian goods within the global fashion industry. As early as 1959, the magazine breathlessly depicted developments in local manufacturing, as illustrated by the following presentation of a clothing workshop:

Will we soon see all Tunisian women dressed in knits? Mohair sweaters, knit outfits, all the jersey [fabrics] that are so fashionable this year are as of now made by the UNFT's new workshop. With new cuts and colors, Tunisian knits can compete with any import, but . . . they will be less expensive, we hope!Footnote 60

Photographs of models in Italian style knits visiting the first Tunisian jersey cloth workshop appeared in one issue, a center-page spread extolling beachwear “entirely made in Tunisia” was included in another, and in yet another issue a National Office of Textiles gala was the subject of an eight-page feature on evening gowns and wedding dresses “made entirely in Tunisia with Tunisian fabrics.”Footnote 61 Depicting the latest styles from the runways of Paris and Milan, notes and captions adjacent to such images directed readers towards local retailers offering Tunisian-made replicas. The excitement about Tunisian couture accentuated the importance of clothing to defining women's identity as modern in terms of its implicit ability to sustain the cutting-edge development of national production.

Over the years, the editors waxed about local products and cheered the revival of the artisanal sector and its specifically Tunisian style. Covers featured young Tunisian models in outfits that combined the modern and the traditional, such as a fuchsia-trimmed burnūs, a Tunisian-inspired jubba from Florence, and a tailored suit trimmed with Tunisian embroidery, whereas articles offered instructions on how to turn a “bedouin blouse” into a beach cover-up.Footnote 62 Despite the fanfare for local production, the editorial proclamation that “the only dress is a Tunisian dress” was not convincing. In impromptu interviews with pedestrians and students, respondents dismissed the poor quality of locally manufactured clothes that most only bought “for lack of choice.”Footnote 63 As one reader elaborated, “I am the first to think that we must buy Tunisian products, to encourage and develop the economy of our country,” but she had thrown away three dresses that shrank in the wash.Footnote 64 While the editors reluctantly agreed on the imperfections of Tunisian clothing, they implored readers to take actions to improve local production and “help us to build a better nation.” Perhaps similarly inspired by the importance of the domestic market for the national textile industry, Femme included reports on production, salaries, revenues, and professional training.Footnote 65 Yet Faiza’s editors struggled to transform fashion into a matter of national priority, placing conscientious consumerism over questions of quality, trendiness, and morality.

In July 1967, the National Clothing Council (al-Majlis al-Qawmi li-l-Aksaʾ) was founded to promote and distribute low-cost packages of locally manufactured “modern, European style clothing” to “encourage the acquisition of decent clothing,” primarily by the working class and peasants.Footnote 66 Advertisements, illustrations, and posters announced these packages in collaboration with local party cells hoping to educate citizens about proper dress and hygiene. “Convinced that traditional clothing is not made for modern work conditions, the Tunisian authorities also believe it is not dignified,” a piece in Faiza reported.Footnote 67 It is not clear whether these efforts bore fruit, as even the reduced costs were likely prohibitive to the target population. In addition, domestic production faced competition from second-hand imports, a profitable market also organized by a state agency.Footnote 68

Tunisian women were far from homogenous; coverage of local traditions, factory workers, and domestic servants in Faiza and Femme attempted to familiarize urban readers with their compatriots of different class and regional backgrounds. Faiza’s staff and audience were composed of middle-class urbanites many of whom benefitted from education, employment, and upward social mobility. While they were committed to national development, operated in close proximity to the regime's inner circle, and shared its class perspective and cultural orientation, they did not mechanically reproduce the party line or share presidential concerns that women's emancipation amounted to debauchery. In fact, readers rarely took note of hemlines prior to presidential statements rendering fashion a foreign threat despite the ubiquity of models in sleeveless and off-the-shoulder tops, bikinis, and backless dresses, and ads for lingerie. Once Bourguiba's attention turned towards women's public appearance, the magazine's editorial team understated moralistic rhetoric while turning purchasing power into an act of patriotism essential to economic development, productivity, and even women's employment. As readers took to the pages of Faiza to debate gender politics, family life, and women's presence in city spaces, they reinforced the association of women with national modernity and the continued fixation on women's bodies and clothing.

FOR “MEN TO REMAIN MEN”

Tunisia's personal status code did not alter patriarchal family structures, for it enshrined the husband as head of the household and its finances (Article 23). Still, Bourguiba often reiterated that the code did not permit women to “reject a father's or a husband's authority,” and that clearly delineated gender roles required “women to remain women and men to remain men.”Footnote 69 The miniskirt owed part of its controversy to its purported threat to male control over the family, as indicated by Bourguiba's comment that such exhibitionism would “make their husbands a laughing-stock.” Neatly linking state feminism (or its limits) to understandings of masculinity and men's behavior revealed that the “woman question” was as much about men as were previous colonial-era deliberations.Footnote 70 Official consternation with the lifestyle of bachelors, habits of youth, and comportment of civil servants indicated a desire to control men as men for at least two reasons. First, chastising wealthy bachelors stemmed from anxiety that uneducated and poor Tunisians were reproducing at a faster rate than other demographics, revealing the middle-class bias of constructions of masculinity.Footnote 71 Second, by delaying their transition towards adult responsibilities, single men challenged the association between marriage and manhood. This section explores how modern womanhood ideology informed gender roles and thus masculinity, as questions of appearance extended to men's bodies. It considers assumptions about masculinity and the boundaries of the nation implicit in what the president, press, and urban reading public had to say about young men during a period of intensified political activism in the 1960s.

Men's dress and manners were “politically charged sites of cultural contestation,” as Wilson Jacob has so insightfully illustrated in the case of interwar Egypt, where masculinity and sovereignty cannot be completely intelligible without reference to the international.Footnote 72 By marketing its Mediterranean beaches to Europeans, the Tunisian state iterated a conception of postcolonial modernity that involved a constant international presence, granting economic weight to the Western gaze. The presence of the West in articulating national culture, understandings of Tunisian manhood, and masculine appearance was evidenced by a scandal about lewd behavior at the Bay's Palladium, an upscale nightclub known for popularizing the jerk, and frequented by the elite, including the son of the president, al-Habib Bourguiba Jr., and Madeleine Malraux, wife of the French minister of culture. This nightclub was closed by administrative order shortly after opening in 1966. The president singled out the club's “corrupt youth, untidily and sometimes very briefly dressed, with their hair long, like that of beatniks,” as the antithesis of their patriotic compatriots, who were then participating in a midsummer youth congress and hence devoted to solving the nation's problems. Dwelling on their appearance, Bourguiba worried that such “barefoot, long-haired imitators of the Beatles” would make a poor impression upon tourists.Footnote 73 National commitment was thus yoked to the gaze of foreigners in defining Tunisian identity along the lines of a sartorially demarcated middle-class respectability.

Men were offered presidential guidance about the contours of proper appearance; in addition to wearing suits, they were instructed to completely button their shirts and to shave daily.Footnote 74 For men reading fashion magazines over the shoulders of their wives, Faiza offered a set of basic “dos” and “don'ts,” extolling button-down shirts but not long hair.Footnote 75 According to La Presse, men's packages distributed through the national clothing initiative included suits because “men's dress is not merely an individual question, it concerns the entire nation.” Ahmad bin Salah, as minister of economic planning, suggested punitive measures against those who appeared in public without proper dress.Footnote 76 Reassuring the public that items distributed through the national clothing initiative would vary, the homogenizing image of the nation-state denied class and regional differences, and rejected individual style. Of uncertain effectiveness, the 1966 imposition of a fine against men who wore long hair penalized bodily comportment and defined transgression through references to European and American popular culture and foreign words in an amalgam of youthful pastimes (dancing, surprise parties) and countercultural trends (the Beatles, the twist, the jerk). In the context of Tunisia's single-party state, these transgressions correlated with political opposition.

In 1961, an increasingly active student movement in Tunisia and abroad began to express dissent from state authority. Leftist students were excluded from leadership positions within the regime-dominated student union, and during the 1962–63 academic year a progressive block defected from the union.Footnote 77 Chafing at an overbearing ruling party, a group of Tunisian Marxists studying in Paris used their clandestine publication, Perspectives, to articulate an approach that diverged from Bourguiba's foreign policy and Cold War stance by stressing social justice.Footnote 78 With ideal manhood closely associated with norms that were unattainable for the majority of state-funded university students, especially marriage and fatherhood, they were swiftly depicted by the regime as spoiled children undeserving of government scholarships. Bourguiba entreated students to study, consider their duty to the nation, ignore material concerns, avoid youthful entertainment, and refrain from wasting their time with political discussions.Footnote 79 Reporting on youth perpetuated this generational divide by painting youth culture in general (also referred to as “yé-yé” as in the “yeah, yeah, yeah” of the Beatles’ “She Loves You” refrain) as producing a false modernity, portraying beatniks and Beatles fans in particular as drug users and petty criminals.Footnote 80 The state trivialized legitimate student concerns about economic development and foreign policy by blurring the distinctions between youth, college students, and superficial cultural movements.

If such press accounts echoed presidential warnings about defending national culture from foreign subversion, there was little consensus on the symbolism of shaggy hair and men's clothing styles. One self-identified nationalist who favored closing the Bey's Palladium made no mention of its dress code but expressed vexation at its exclusive nature.Footnote 81 Another letter addressed to Jeune Afrique expressing disdain for pampered students, focused on their failures as model citizens, wild behavior, and neglect of moral values, but again paid no attention to clothing.Footnote 82 A series of interviews in Faiza are indicative of diverging opinions about men's appearance. ʿAzuz, a thirty-year-old civil servant who always wore a tie and shaved, criticized his roommate ʿAziz for his “pants that were never ironed and Beatles-style hair,” but the twenty-four-year-old artist retorted that dress should be practical and not merely about appearances: “You have to change people's mentality, not their clothes.”Footnote 83 A merchant in the madīna identified as Si Bashir owned a suit that he wore on occasion, but when asked why he mainly dressed “Tunisian,” the fifty-seven-year-old replied, “My goodness, I've never thought about it.” He stated, “young people should dress the way they want to,” as did his eight children who “dress European style.” When goaded by a question about indecent dress, he scorned shameful styles and young men who dress like women. Toward the end of the interview, he distinguished between hygiene and imposing a dress code, and concluded by admiring the variety of bedouin dress: “We are free, right? Let each one dress as he sees fit.”Footnote 84 These comments are revealing for how they refuse the middle-class basis of respectability and reject the association between traditional Tunisian clothing (whether his own or that of bedouin) and backwardness. Whereas ʿAziz dismissed standardized appearance as superfluous, Si Bashir identified diversity and autonomy in dress as a mark of the self-determined postcolonial citizen.

Where Bourguiba succeeded was in drawing attention to men's behaviors, unintentionally opening the door for further scrutiny of masculinity. In a series about love that extended from the spring of 1966 into late 1967, Faiza and its readers dissected the implications of men's actions and attitudes for women's emancipation and national progress. The series began with eight anonymous young women discussing how courtship privileged young men. M., a college student, exposed a sensitive paradox: girls could only express love within marriage, but boyfriends dumped them if they mentioned marriage. Similarly, Tunisian men in Europe who acted very “liberated” toward their girlfriends returned to Tunisia to insist on marrying a young virgin, illustrating a sexual double standard. Two other students, J. and E., concurred, “If she's not a virgin, it's over,” whether the young man had gone out with thousands of girls, or only two or three.Footnote 85 By highlighting such discrepancies, these young women challenged self-serving male gender politics in relation to dating, premarital intimacy, and virginity.

Love, sex, and marriage were hot topics, and a similar conversation with twelve young men aged twenty to thirty soon appeared. Ahmad, a married thirty-year-old, chided the idea of male dominance: “Tunisians live the ‘myth’ of the man as a protector who has to be in charge of everything.”Footnote 86 Yet other participants in the conversation upheld male prerogative. Khalid, also married, scorned women's premarital sexual relations: “I will only marry her if she is a virgin, and I will only love her if she is a virgin. It's a very selfish position.” Al-Munsif, a twenty-one-year-old student, admitted: “Every time I get to know a girl, I love her, and every time that I sleep with her, I don't love her anymore.” They believed their generation was ahead of “society,” and recognized that courtship practices were unjust towards women, yet succumbed to the restrictions of the Tunisian environment. They epitomized how men who came of age after independence were caught between social and familial pressures that reinforced male privilege, a filial attachment to Bourguiba, and commitment to women's rights.Footnote 87 By refusing to recognize their own complicity in perpetuating patriarchal social norms and family structures, they not only reinforced sexual double standards, but also placed men's intimate lives beyond public scrutiny.

Female readers responded to the arrogance of these young men with wit and biting condemnation.Footnote 88 Summarizing a conversation with twenty of her friends, one wrote: “The young Tunisian man [garçon], whether he is at the university, in high school, in the administration, or in a factory, is always selfish.” She argued that male domination produced gender discrimination in the workplace and nefarious practices at home: “Whether in the office or at home, he acts as if he is in charge . . . in the life of a couple, there is neither master nor slave.”Footnote 89 Outraged by the pretense that sexual intimacy was a masculine prerogative, another wrote:

Khalid demands that a woman be a virgin. I would like to ask him why he allows himself to have numerous adventures without conceding that women can have them as well? Isn't that unjust? . . . When our country was colonized, it was up to the French to define our freedoms. Now that we are independent, is it your turn, the men, to act towards women as colonizers?

Rejecting al-Hadi's claim that a man's domination was a universal sign of affection, she concluded: patriarchal attitudes are “not universal as you seem to be convinced, but only applicable to underdeveloped countries. Let's figure out how to end our underdevelopment, come on!”Footnote 90 Her condemnation of patriarchal privileges reframed debates about masculinity, encouraging reform within the nationalist idioms of progress and anticolonial liberation.

Student mobilization surged in December 1966, June 1967, and January and March 1968, partially coordinated by the Perspectives group. The state swiftly arrested, expelled, or imprisoned protestors, often allowing only farcical political trials.Footnote 91 Considering popular perception of students as immature, youth culture as degenerate, and their criticism attributed to misguided foreign ideologies; resistance to the one-party state was configured as the disobedience of spoiled and ungrateful children.Footnote 92 These harsh reactions to student grievances were akin to ruling-class responses to youth resistance in West Germany, the US, France, the Soviet Union, and China in 1968; though by then parts of the Tunisian press were beginning to change their tone.Footnote 93 In chastising youthful bachelors, Bourguiba hoped to reassert the state's patriarchal authority over male citizens it considered juvenile. While a common critique of youthful fads was their superficiality, presidential attempts to define manhood and male respectability through clothing choices failed to resonate. Rather, the conversation about appropriate behavior provided an opportunity for middle-class Tunisian women to argue in the protected space of a magazine for deeper transformations, challenging the patriarchal privileges of heteronormative masculinity while still abiding by a national telos of progress.

CONCLUSION

Tunisian independence coincided with a demographic boom, allowing the government to celebrate the younger generation as an embodiment of the nation's promising future. Nationalist commitment in this new society, however, required public performance of obedience to the single-party state in particularly gendered forms. For men, nationalist calls to wear a suit were intended to create the homogenous appearance of a politically unified modern nation that subsumed regional differences and erased class struggles under a middle-class veneer of adult masculine responsibility. Women's smiling faces, tailored skirts, and trim sweaters suggested the vibrancy of a new generation of students and public sector employees liberated by the postcolonial state's legislation. Just as student activism challenged single-party rule, women's stylistic improvisations threatened the state-envisioned patriarchal order even as it was encouraged by a consumerist developmental logic.

Bourguiba instrumentalized his legal training to intervene in family matters, weakening the power of individual men without altering the patriarchal core of Tunisian masculinity. For all its secularism, the authoritarian context confined the possibilities of Tunisian state feminism, marginalizing women outside circles of power and silencing their voices. Government concern with declining morals zeroed in on practices delegitimized as foreign, signaling spaces beyond its authoritarian control. Even modern secular women reframed consumption and trendiness as a commitment to the nation's traditional roots and its purported socialist development. Middle-class urban women readers, in turn, mocked the sexual double standards of Tunisian men. As such, they pushed for greater transformations and proposed alternative futures, even if the ruling elite and coastal middle class accepted the basic parameters of the limited reform agenda.