A recent wave of publications indicates a lively interest, within scholarly communities and public discourses alike, in pairing China and India together. The breadth and volume of academic scholarship suggests that the China-India pairing offers a powerful opportunity to rethink a range of entrenched disciplinary limitations, from strains of Eurocentrism and the regionalism of area studies to the narrowness of nation-centric paradigms and the dominance of capitalist circulation. Yet, much of this scholarship lacks a self-reflexive contemplation on its own relevance, approach, and stakes: why pair China and India together, how to do so, and to what ends? This special issue aims to open up a conversation on these questions of method. The issue collects interventions from across the humanities and social sciences – namely art history, religion, history, literary studies, cinema studies, and urban studies – that showcase innovative research on Chinese and Indian texts, materials, and ideas alongside a sustained reflection on the reasons for and approaches to studying China and India together.

In line with recent methodological reflections, this issue harnesses a practice-oriented approach to method, wherein knowledge produced from analyses of specific objects or phenomena can be productively delinked, if only momentarily, from the particularities of specific examples to address a wider range of concerns (Chen Reference Chen2022; Rojas Reference Rojas2019). One argument all the articles in this issue jointly extend is that the China-India pairing can serve as a crucial tool through which to expose and unsettle disciplinary assumptions that far exceed the materials or contexts immediately at issue. By articulating these larger interventions on the scale of method, we aim to sketch a shared critical idiom for China-India research across differences in orientation and focus, while at the same time delineating some of the contributions of China-India studies in a variety of disciplinary contexts.

This issue therefore addresses two main communities of readers. Firstly, we endeavor to reach those scholars whose research engages with the conceptual pairing of China and India or cuts across the borders, archives, and languages of the Chinese and Indian spheres. We hope that our explicit reflections on the unique challenges and opportunities of conducting such research will help launch a discursive space for reflexivity at the intersection of multiple disciplines, thereby combatting the tendency for China-India research to remain confined to discipline-specific silos. Secondly, this issue seeks to articulate the significance and richness of the China-India pairing for those whose research may not fall within China-India studies, but who are similarly committed to intellectual practices of decentering and rethinking the frames of transnationalism, regionalism, and global capitalist integration.

In this introduction, we first tackle the “why” by sketching the intellectual stakes that shape the practice of studying China and India together. The first section discusses rationales commonly offered as justification for pairing China and India together. Moving away from recent framings of China and India as “Asian superpowers,” this section offers an alternative articulation of the importance of China-India thought, one that is better-suited to our current political and academic climates. The China-India pairing, we suggest, could provide a crucial methodological tool for confronting the inequities and power imbalances that persist across disciplines and transnational fields of study today. We then turn to the “how”: the second section outlines a history of the China-India pairing from the first century CE to the end of the twentieth century. We explore how a range of historical actors, including monks, state leaders, and members of civil society, paired China and India under shifting political circumstances and with differing objectives. We focus on periods of particular China-India significance, from the premodern spread of Buddhism into the late-twentieth century era of economic reforms and offer an assessment of the methodological approaches recent scholarship has extended to studying each of these periods. Finally, we highlight some of this issue's contributions to and innovations upon this prior work and introduce each of the articles that follows.

Intellectual Stakes

Why pair China and India together in our current academic work? One common rationale stems from the ethos of the “transnational turn” of the 1990s and early 2000s, which was marked by an increased engagement across the humanities and social sciences with the connective affordances and asymmetries of globalization. Proponents of what may heuristically be called the “Asian superpowers rationale” have suggested that the China-India pairing proves crucial to understanding a globalized world, given the two nations’ status among the world's largest economies, as central hubs for transnational flows of peoples and goods, and consequently, as key determinants of the global future in everything from world politics to climate change. As the editors of the recent Routledge Handbook of China-India Relations write,

The relationship between China and India is widely regarded as one of the central pivots of world politics. While China-US relations will be determinative of global security, global governance, and even global prosperity, the interactions between the two Asian giants could well become the second most consequential bilateral relationship in international politics (Bajpai et al. Reference Bajpai, Ho and Miller2020, p. 1).

Beyond the disciplinary grounds of International Relations, recourse to the Asian superpowers rationale also informs how scholars have justified studying China and India together in the humanities and social sciences. The editors of a 2018 volume, What China and India Once Were: The Pasts that May Shape the Global Future, address the question they pose of “why China and India?” as follows:

The 2015 United Nations Climate Change Summit offered compelling evidence of what so many other global indicators, from stock market shifts to security threats to trends in popular culture, have long suggested to attentive observers: China and India have become decisive players in determining the world's future. […] That the influence of China and India is on the rise is not news, of course. Their entry onto the world stage has been on the radar of politicians, business leaders, scholars, journalists, and others for several decades (Pollock and Elman Reference Pollock and Elman2018, pp. 2-3).

Despite its varying iterations, the Asian superpowers rationale gains coherence from a widespread sense that China and India are now exerting new levels of economic and geopolitical influence on the world stage. Scholars have argued that China and India's current centrality in discourses of international relations, global economics, climate change, and so on necessitates commensurate academic attention devoted to studying their histories, cultures, and societies together.

While the Asian superpowers rationale certainly continues to hold sway in several respects, recent developments have arguably altered its tenor and some of its founding assumptions. In 2022, amid waning globalization and the rise of insularity worldwide – a breeding ground for authoritarian politics, racial and ethnic violence, and widening social, economic, and information inequalities – narratives of China and India “on the rise” seem increasingly out of joint. How, then, in this changed world, can we articulate the persistent need for and importance of China-India research? How, in this process of China-India research, can the neglect of other pertinent countries and regions be explained and rationalized? And, importantly, how can we do so while remaining cognizant of, but without uncritically acquiescing to, the market-based pressures on academic publishing, the political agendas of funding bodies, and the increasing corporatization of university spaces that all inevitably mark how we articulate the significance of academic work in the humanities and social sciences?

A deeper reckoning with the long intellectual history of studying China and India together could offer one trajectory toward articulating the contemporary relevance of the pairing. Far predating the transnational turn, China-India academic research finds its intellectual roots in mid-nineteenth-century colonial epistemologies, and subsequently in early-twentieth-century anticolonial discourses (Sen Reference Sen2021). Over the course of the twentieth century, intellectual engagements with the practice of thinking about China and India together have shared a desire to decenter political and conceptual frames of dominance and to disrupt hierarchical structures of power. Pan-Asianist imaginaries of the colonial period, for instance, envisaged China-India oneness as a site of resistance and as an emancipatory stance against European and Japanese colonial and imperial subjugation. Decades on, during the mid-century years of decolonization and nation-building, a host of intellectual, cultural, and civic collaborations conducted under the banner of China-India diplomacy proved an essential tool in forging a Third World against the growing polarization of a bloc-led world stage. We return to discussing this rich history of China-India thought in the following section, but these brief snapshots suffice for now in suggesting that efforts to subvert and reimagine dominant, restrictive world orders have often involved practices of thinking China and India together and of apprehending their intertwined pasts, parallel presents, and shared visions for the future.

Positioning current China-India research as the latest instantiation of this historical intellectual practice can bring the enduring stakes of this work into view. Through the twentieth-century, China-India studies has witnessed intellectuals harnessing this conceptual pairing as a strategic tool for challenging unequal structures of power and opening up alternative horizons of thought. In a way, the unfinished projects and unfulfilled desires of its anticolonial, anti-imperial, and anti-nationalist forebears bestow the China-India pairing with an ethical drive to disrupt entrenched hierarchies, expose inequalities, and forge new contours of academic work. While the Asian superpowers rationale emphasizes the position of centrality that China and India occupy on the global stage, perhaps the current significance of China-India research lies more in its long-standing commitment to decentering and opposing dominance. We may conceive of present-day China-India studies, therefore, less as a self-contained field in its own right and more as a portable conceptual pairing, capable of being activated in various academic contexts to expose blind-spots, productively unsettle assumptions, attend to difference and inequity, and push fields of study in uncharted critical directions. Rather than consolidating China-India research under a unified rubric of methods, then, this issue expresses a shared intellectual commitment to decentering, jointly articulated by China-India scholars across disciplinary boundaries.

Drawing from its anticolonial roots, an important aspect of the China-India pairing's decentering potential is its capacity to dethrone the West from its long-held position at the epistemological center of academic work. Several articles in this issue explore this potential by, for instance, grounding the production of knowledge – and not simply its reception, as in earlier colonial models – in China-India practices of cultural expression (Zu) and scientific exchange (Ghosh). Beyond provincializing the West, the work of decentering can also interrogate problematic paradigms and trends dominant in specific disciplinary contexts, such as the diffusionist “center-periphery” model still common in studies of Buddhism (Kim), the valorization of historicist connection in transnational literary and cultural studies (Grewal), and methodological nationalism in urban studies (Frazier). The articles also extend a decentering lens to the nation-states in question, by examining practices of China-India thought located outside the geopolitical borders of China and India (Nasser) and by embedding the China-India pairing within larger circuits of transnational exchange (Van Fleit). In these ways, the issue suggests that China-India work may begin from the common ground of shared intellectual commitments, which nonetheless open multiple ways in which the conceptual pairing can meaningfully intervene in diverse academic spheres.

One success of the transnational turn has been the emergence of a host of newer fields – Global Asias, Global South Studies, world/global literary and cultural studies, migration studies, and so on – that seek to dismantle the nationalized and siloed structures of the more traditional disciplines. Many of these fields have only recently found sources of institutional support and recognition, but their continued vitality may ultimately rest upon their ability to reconcile the globalized habits of thought that arguably led to their formation with the current narrowing and reshaping of earlier conditions of mobility, circulation, and interconnection. China-India research, which thrives in these transnational, multidisciplinary, and collaborative spaces, holds the potential to spark precisely such debates. The last two years have witnessed a dramatic ossification of the national borders between China and India: pandemic-related travel restrictions, armed conflict in and increased militarization of the contested borderlands, state-sponsored Islamophobia, religious and ethnic violence, a violent tightening of state control over Xinjiang and Kashmir, and a sharp negative turn in mutual public perceptions. As China-India scholarship grows in the shadow of these realities, the conceptual pairing could offer transnational fields a renewed critical engagement with foundational tenets such as interconnectivity and solidarity, as well as reconceptualized methodological strategies for transcending the hold of the nation.

Having articulated the shared intellectual commitments that lend current China-India work a coherence across disciplinary boundaries and form a common point of departure, we now turn to considering the history of the conceptual pairing alongside a discussion of relevant recent scholarship.Footnote 1

The Pairing of China and India

The First Millennium

The pairing of China and India is not new. The spread of Buddhism from various parts of South Asia to sites in the present-day People's Republic of China (PRC) around the first century CE necessitated thinking of China and India together. The spread of Buddhism, which led to the transmission of several aspects of Indic traditions to China – including languages, ideas of renunciation and reincarnation, and literary genres – triggered multifaceted discourses, debates, and the comparative examination of these two culturally, socially, and politically distinct and diverse regions. This early pairing of China and India was sometimes part of polemical and sectarian debates and at other times the result of inquisitiveness about a foreign land that the followers of Buddhism in China considered sacred. Already in the second century, in a work credited to a person known as Mouzi 眸子, the sophistication of Indian society was being articulated and compared to that of China (Keenan Reference Keenan1994). Similarly, a sixth-century compilation of debates between Daoists and Buddhists, known as Xiaodao lun 笑道論 (Laughing at the Dao), highlighted the cultural sophistication of India with reference to its aim to legitimize and establish the practice of Buddhism in China. The Daoists put forward a counter argument stating that Laozi, the founder of their tradition, had in fact traveled to India and taught the Buddha (Kohn Reference Kohn1995). Such comparisons and associated imaginary connections to the land of the Buddha were common in China throughout most of the first millennium CE. Within this context, the writings of the Chinese monk Yijing 義淨 (636-713), who traveled to India in the seventh century, stand out.

Yijing was one of three famous Chinese Buddhist monks who visited India and returned to write accounts of what they had witnessed there.Footnote 2 Compared to the earlier writings of Faxian 法顯 (337-c. 422) and Xuanzang 玄奘 (600?-664),Footnote 3 Yijing's two works, Nanhai jigui neifa zhuan 南海寄歸內法傳 (A Record of the Inner Law Sent Home from the Southern Seas) and Da Tang Xiyu qiufa gaoseng zhuan 大唐西域求法高僧傳 (Biographies of Eminent Monks who went to the Western Regions in Search of the Law), portray the diversity of Buddhist practices in China and India from a comparative perspective and reveal the complex connections between the two regions that included sites, polities, and Buddhist communities in Southeast Asia and Korea (Sen Reference Sen and Saussy2018). Yijing provides a comparative analysis of Buddhist practices in China and India to explain the reasons for the differences in the application of monastic rules in China. Sometimes he advocates reforming the practices in China in order to follow the Indian tradition, but at other times he acknowledges that the Indian precedents cannot be applied in China and recommends modifications. For instance, Yijing observed that, when having meals, monks in India sat on chairs with their feet on the ground. In China, however, he notes that initially the monks sat squatting on their heels when eating. Later, they started sitting cross-legged at mealtimes. Based on this comparative observation, Yijing suggested that, since the Buddha sat with his feet on the ground, the correct way for the Chinese clergy was also to adopt this Indian practice (Li Reference Li2000, p. 23; Sen Reference Sen and Saussy2018, p. 361). However, when discussing the example of cleansing one's body or robes before offering salutations, Yijing makes an exception for the Chinese monks and says that, since they lived “in a cold country, it is rather difficult for them to behave in accordance with the teachings, even though they wish to do so” (Li Reference Li2000, p. 87; Sen Reference Sen and Saussy2018, p. 362). Yijing's works also point out the complexities of intra-regional connections by highlighting the importance of Southeast Asia as a place for learning Sanskrit and the travels of Korean monks to India through China. Indeed, Yijing may have been one of the first persons to pair China and India employing a framework that offered both comparative and connective perspectives.

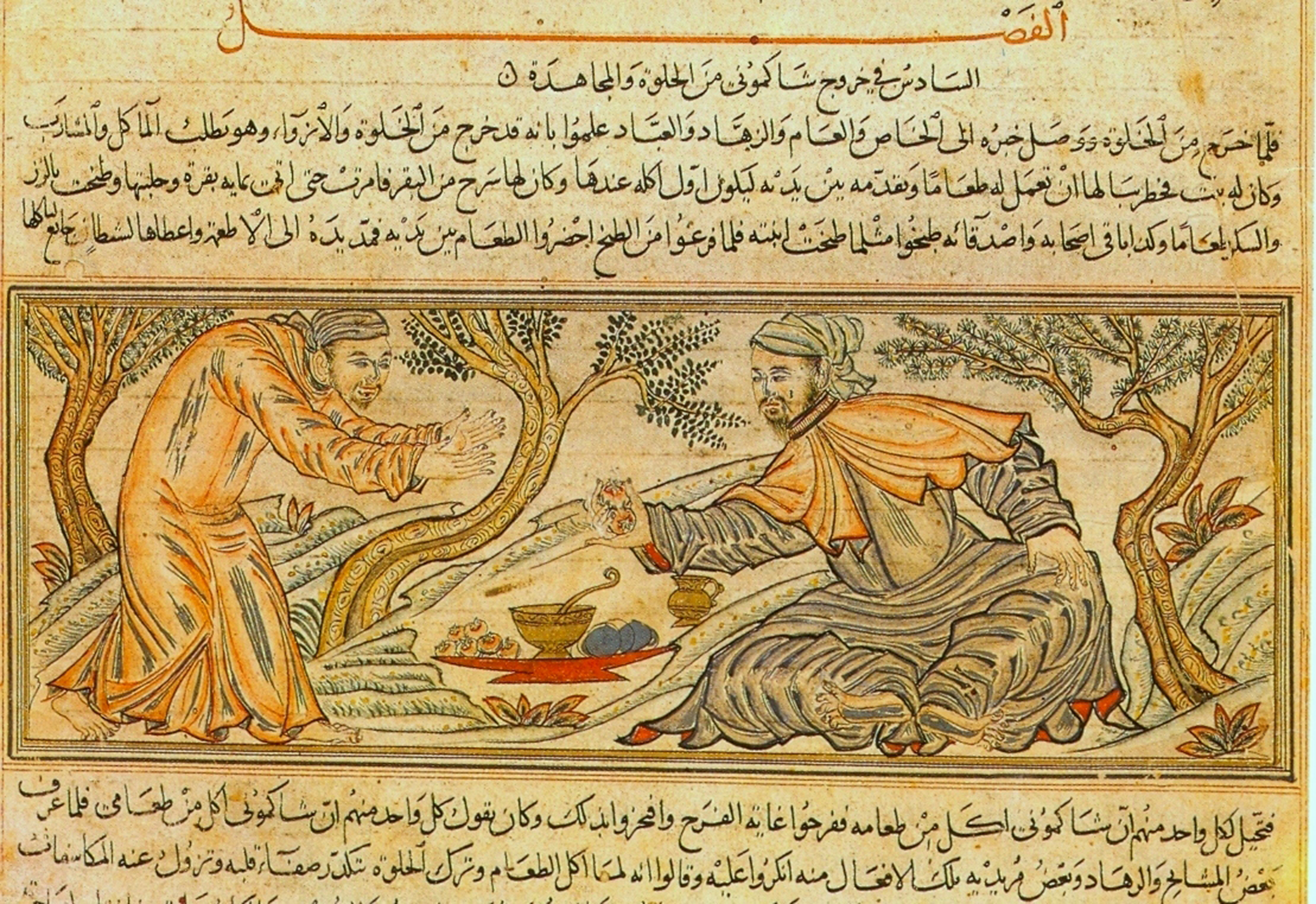

The pairing of China and India during this Buddhist phase manifested itself in several other ways: in artistic representations, translation activities, astral science, fiction writing, etc. Such pairings differed from Yijing's more focused and limited discussion of monastic practices. Moreover, the efforts to understand and pair the two regions were not limited to people from India and China. The followers of Buddhism in Japan, for instance, were not able to visit the sacred land in India before the seventeenth century. Instead, their knowledge about the region primarily came from Buddhist texts written or translated in China. Records of Xuanzang's visit to India played a significant part in enhancing knowledge about the region and also triggered imaginations of the sacred place. This resulted in the emergence of pictorial representations of India and Xuanzang's travels in a fourteenth-century scroll known as Genjō Sanzō-e 玄奘三蔵絵 (Illustrated Life of Xuanzang). The scroll includes several illustrations of episodes associated with Xuanzang's stay in India (Saunders Reference Saunders2012). Maps of the “Five Regions of India” (Gotenjiku zu 五天竺図, Figure 1), also appeared during this period, with the earliest one preserved in Hōryū-ji temple in Nara, Japan. At the other end of the Buddhist world, almost at the same time, in Illkanate Iran, paintings depicting the life of the Buddha (Figure 2) appeared in an illustrated edition of Rashīd al-Dīn's Jami al-Tavarihk (World History) and in the sixteenth-century work Majma al-tavarikh (Chronicles) by Hagiz-i Abru. The images are based on the biography of the Buddha that Rashīd al-Dīn composed from the information provided by a Kashmiri and two Chinese informants (Jahn Reference Jahn1965; Canby Reference Canby1993). These examples from Japan and Iran illustrate how the pairing of China and India in the larger context of the spread of Buddhism was undertaken by people from outside these two regions using distinct sources and for varied purposes.

Figure 1. Gotenjiku zu 五天竺図, Map of the Five Regions of India, Horyu-ji temple, Nara.

Figure 2. Persian rendition of the assault of Mara from the biography of the Buddha (fourteenth century). Wikimedia, Creative Commons. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Buddha_offers_fruit_to_the_devil_-_from_Jami_al-Tawarikh.jpg

The millennium-long interactions between China and India fostered through Buddhism therefore indicate complex circulations of people, ideas, and objects, as well as the contributions and involvement of people from several different regions. Indeed, there were multiple overlapping factors in the spread and establishment of Buddhism in China, which involved intricate processes of understanding, misunderstanding, adaptation, reinterpretation, imagination, connection, disconnection, propagation, prosecution, patronage, and rivalries. The diversities of China and India and the manifold overlapping factors that fostered connections and provoked comparisons during the first millennium CE suggest the employment of a multidisciplinary approach, which could adequately address the issue of the agency of objects (Latour Reference Latour2005), the subtleties of mobility (Adey et al. Reference Adey, Bissell, Hannam, Merriman and Sheller2013), the intricacies of connected histories (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam1997), the “art of convergent comparison” (Duara Reference Duara2015), and so forth. In other words, the study of Buddhist connections between China and India cannot be constrained by geographical and disciplinary boundaries or nation-state framings, nor by neglecting several other parallel and connected processes, such as economic, political, and social conditions and transformations.

Two books have attempted to address these intertwined issues and made methodological interventions in their examinations of the Buddhist connections between China and India. Liu Xinru's (Reference Liu1988) Ancient India and Ancient China covers these connections from the initial spread of Buddhism in the first century to the seventh century. This work established a new paradigm for analyzing such connections by placing the spread of Buddhist ideas and objects in the broader contexts of commercial interactions and urbanization. Additionally, Liu used theories and concepts from the fields of economic anthropology and urban studies to frame her study. Tansen Sen's ([2003] Reference Sen2016) Buddhism, Diplomacy, Trade examined subsequent China-India connections from the seventh to the fourteenth centuries. Like Liu, he also emphasized the entwined nature of religious and commercial exchanges between the two regions. Furthermore, he explained the disconnections in Buddhist contacts that, according to Sen, took place in the ninth-tenth centuries, when China emerged as one of the “central realms” of the Buddhist world and no longer depended on the transmission of doctrines nor yearned after sacred sites located in India. After the tenth century, China-India interactions were dominated by commercial exchanges. Sen used the world system framework devised by scholars such as Janet Abu-Lughod (Reference Abu-Lughod1989) to study this post-Buddhist phase, and demonstrated the importance of analyzing China-India interactions within the larger Afroeurasian context.Footnote 4

Beyond these studies, which focused on the connective aspect, scholars have also conducted comparison on various issues related to the practice and teaching of Buddhism in China and India.Footnote 5 Comparative studies on non-Buddhist issues are rare and often methodologically challenging. One such example is the edited volume by Kaushik Roy and Peter Lorge (Reference Roy and Peter2015) entitled Chinese and Indian Warfare, which attempts to explain several military episodes and strategies in pre-twentieth-century China and India by juxtaposing chosen examples. The method of juxtaposition here entails one contributor writing on one region and another on the other. This is a convenient but potentially problematic academic exercise, especially when authors do not read each other's contributions before offering their analyses of the rationale for or outcome of the pairing.

The Second Millennium

The pairing of China and India during the second half of the second millennium, when connections between Asia, Africa, and Europe became more intensive and the actors, circumstances, and sites involved diversified immensely, also requires crossing geographical and disciplinary boundaries. The writings of Marco Polo (1254-1324) and Ibn Battuta (1304-1369), the voyages of Zheng He 鄭和 (taking place between 1405 and 1433), the European colonial expansion, and the circulation of multiple commodities ranging from opium to silver are indicative of the vast geographical span and the diversity of issues that anyone attempting to pair China and India must consider. Indeed, the connections between China and India during this “imperial phase” (Sen Reference Sen2017) were part of multiregional trade and smuggling, local and global conflicts over access to production sites, and the circulation of indentured labor to plantation sites across several regions of the world. Issues of territorial expansion, explorations of and disputes over border-making, independence movements, and anti-colonial alliances entangled China and India in many ways. Some of these connections and entanglements resulted in comparative musings, provoked interest in obtaining new information and knowledge about each other, and led to negotiations about commercial exchanges and territorial concerns often involving multiple parties.

All these aspects make this period extremely complex to study and the pairing of China and India within an effective framework challenging to accomplish. The pairing often cannot be constrained within any single academic discipline, whether economic and colonial history, international relations, or migration studies. Moreover, the plethora of relevant sources written in many different languages now dispersed in archives and libraries in multiple countries makes research into this all the more difficult. Given the diversity of topics and sources, some scholars have considered the China-India pairing through a single issue but within a broader conceptual and/or geographical framework. Mathew Mosca's (Reference Mosca2013) From Frontier Policy to Foreign Policy is an excellent example of such a study. Mosca offers an in-depth analysis of Chinese sources to explain how Qing China's perception, engagement, and policy regarding British India changed between 1644 and 1860. Focusing on the frontier regions of Tibet and Xinjiang, Mosca outlines various cartographic projects, discourses on geographical knowledge, and the development of “strategic thought” about India in Qing China. Despite focusing on a specific topic and region, the issues discussed in the book pertain to the wider facets of British colonial expansion, the circulation of knowledge, and the later process of border-making between the PRC and the Republic of India (ROI). Another outstanding work on this period is Andrew B. Liu's (Reference Liu2020) Tea War. Liu's is a comparative study of the complicated ecosystems of the tea industry in China and India that integrates the topics of connections and competitions within a broader analytical framework of capitalist political economy. The use of local sources written in multiple languages, Liu's archival research, and the analysis presented in his book constitute a significant contribution to the method of pairing of China and India that could be applicable to any period of study.

The aforementioned volume, What China and India Once Were (2018), focuses on a similar period (termed here the “early modern period” i.e. roughly between 1500 and 1800), but attempts a different methodological experiment. Rather than the combined approach of the studies discussed above, the editors Sheldon Pollock and Benjamin A. Elman frame their volume as an exploration of how to conduct comparison while temporarily bracketing away the “densely woven fabric” of China and India's “connected history” (Pollock and Elman Reference Pollock and Elman2018, p. 11). The editors begin from the widely-accepted premise that the method of comparison is problematic given its imbrication with colonial epistemology, which treats non-Western objects of study as “deviant and even deficient” from the imposed “European ‘standard’” (p. 12). But instead of turning to “connected history” as “a corrective or even replacement for comparative study,” the editors propose the method of “cosmopolitan comparison,” defined as “the direct comparison of non-Western entities” without the mediating presence of a European norm (p. 12). “Cosmopolitan comparison,” the editors write, “requires that we actively try to bracket the Western objects – painting, poems, power formations, whatever – that have functioned as the standards, in order to gain as undistorted a view as possible of the non-Western objects of comparison” (p. 14). The volume therefore takes China and India as “comparative partners,” the pairing of which makes visible each as “radically” and “equally” different from the other (p. 17). Such an understanding of the past, the editors argue, can help academic and mainstream readers alike make better sense of China and India's present positions on the global stage.

While the methodological formulation of “cosmopolitan comparison” recovers comparison to some extent from its disrepute, particularly in historiographical scholarship, the volume as a whole nonetheless remains mired in the challenges of practically implementing such comparison. In terms of its organization, the volume includes essays that also employ the above-mentioned method of juxtaposition, but instead of having separate chapters on China and India, each chapter features two scholars as co-authors working collaboratively. This approach is certainly an improvement to the alternative model of juxtaposing two separate chapters on one specific issue that make no attempt to relate to each other. But the volume's underlying assumption that comparison and connection can be delinked ultimately proves problematic for studying China and India, given how fundamentally both ways of knowing contributed to the very formation of all aspects of society discussed here, from art and literature to religion and science. The volume's orientation toward both scholarly audiences and “the general educated reader” further weakens its potential to intervene in public discourse on China and India, for the absence of footnoting and a comprehensive bibliography erases the possibility of pointing interested readers toward more fuller accounts of China and India's pasts.

The Late Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

The period after the Opium Wars (1839-1842; 1856-1860) witnessed a rapid expansion of China-India interactions, leading to an increased movement of people, goods, discourses on border-making, and diplomatic exchanges. Many of these aspects continued to feature in the contacts between an independent India and a communist China during the 1950s and even later. The first half of the twentieth century was particularly important for the pairing of China and India for multiple reasons. First, the period saw the emergence of a formal field of study that paired China and India. In 1927, Alexander von Staël-Holstein (1877-1937) set up a “Sino-Indian Institute” at the former Austrian embassy in the Legation Quarter in present-day Beijing. Staël-Holtein also established a “Sino-Indian” research cluster and a publication series with funding from the Harvard-Yenching Institute. The scholars involved with this cluster were mostly interested in the linguistic analysis and translation of Chinese Buddhist texts. Some, such as Sylvain Lévi (1863-1935), went on to train the next generation of scholars who similarly pursued research on the Buddhist connections between China and India (Sen Reference Sen2021).

Second, the idea of pan-Asianism, originally developed by the Japanese scholar Okakura Kakuzō (1863-1913), led to the pairing of China and India in several ways. In Japan, the pairing seems to have resulted in efforts to combine the histories of China and India to promote the idea of “Asian” or “Eastern” history. The “basis of this plan,” as has been noted (Matsuda Reference Matsuda1957, p. 2), was the “reconsideration of Japanese culture” itself. Additionally, in Okakura's “Asia as one” formulation, the pre-colonial cultural linkages between Japan, China, and India, fostered primarily through Buddhism, could be rejuvenated to create a pan-Asian identity and counter the dominance of Europe and the European conceptualization of the world. While several Chinese and Indian intellectuals initially supported this idea, its appropriation by the Japanese military, in the form of the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” propaganda scheme, resulted in a modification of pan-Asian discourse with the emphasis now placed squarely on China and India. A key figure in this modified conceptualization was the Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), whose visit to China in 1924 not only triggered various cultural exchanges between China and India but also writings on each other by scholars, novelists, and poets, as well as artistic productions showing the mutual influences of those based in the two countries.

In a third development, the two strands of pairing China and India mentioned above merged in the efforts of Indian intellectuals belonging to the Greater India Society, established in Calcutta in 1926. Inspired by Lévi, the members of the Society promoted the nationalist idea of an expansive Indian civilization across Asia attained through what they considered to be the “spiritual conquest” of East and Southeast Asia. Within this context of the “pan-Asiatic expansion” of Indian culture, scholars such as Kalidas Nag (Reference Nag1926) and P.C. Bagchi promoted the idea of a thousand years of cultural contacts between China and India, with the latter exerting a profound influence on the former. Bagchi's (Reference Bagchi1927) initial essay on the topic, published as part of the Greater India Society Bulletin series in 1927, was subsequently expanded in book form in 1944 and reprinted several times starting in 1950. Titled India and China: A Thousand Years of Sino-Indian Cultural Contact, Bagchi's (Reference Bagchi1944; Reference Bagchi1950) book became one of the first and most widely read narratives of the longue-durée interactions between the two regions.

Such pairings of China and India invoking longue-durée cultural interactions also took place in China (see, for example, Jin Reference Kemu1957), often in the context of a renewed call for Asianism, the idealization of a forthcoming “Asian century,” and the promotion of “Afro-Asian solidarity” that emerged after decolonization in the late 1940s. Such pairings of China and India in a superficially constructed narrative of a thousand years of Buddhism-inspired “friendly” interactions and in the hope of continued affable relations in the contemporary period became a common trope in civil-society discourses, government propaganda publications, and academic writings. At the same time, however, analytical studies comparing models of political and economic development in the ROI and the PRC, as well as critical examinations of the interactions between these two new states, also started appearing in the 1950s. A major watershed in the paring of China and India came in the late 1950s, with an initial establishment of diplomatic relations between the newly-established nation-states followed by a rapid deterioration of bilateral relations and the 1962 war. From then on, writings pertaining to the border dispute, international relations, and speculations about future armed conflicts have dominated studies that pair China and India.

In recent years, several studies have started to reexamine the post-Opium War period. Peter van der Veer's (Reference Van der Veer2014) The Modern Spirit of Asia uses comparative analysis to examine the issues of modernity, spirituality, and secularity in China and India during the early twentieth century. In a second book, The Value of Comparison (2016), van der Veer makes the following case for comparison from the disciplinary perspective of anthropology:

The marginalization of comparative analysis is particularly glaring in history, the national discipline par excellence. However, it has also become glaring in anthropology, which was supposed to be comparative from its beginning. […] There is no escape from comparison when we deal with “other societies” as historical sociologists or anthropologists, since we are always already translating into Western languages what we find elsewhere, using concepts that are derived from Western historical experience to interpret other societies and other histories. It is therefore necessary to engage one's implicit comparison and make it more explicit (van der Veer Reference Van der Veer2016, p. 8).

Van der Veer's call for recovering comparison and making it explicit resonates with the volume Pollock and Elman would later publish, but van der Veer's approach to grappling with the centrality of the West in comparative methods differs from that of the edited volume. He writes,

One of the greatest flaws in the development of comparative sociology seems to be the almost universal comparison of any society with an ideal-typical Euro-American modernity. It would be a step forward to compare developments in modern India and modern China with each other. That does not imply a straightforward “provincializing” of Europe, since Europe and the United States are crucial in the formation of Indian and Chinese modernity, but an understanding of the ways in which similar challenges and influences have produced very different societies in India and China (van der Veer Reference Van der Veer2014, pp. 12-13).

Unlike Pollock and Elman, whose “cosmopolitan comparison” strives for “direct comparison of non-Western entities,” van der Veer's approach allows for a more flexible treatment of the West given its formative role in China and India in the modern period, an issue “cosmopolitan comparison” sidesteps since the volume focuses on the period prior to “the coming of Western modernity” (Pollock and Elman Reference Pollock and Elman2018, p. 8). Temporal focus aside, the differing treatments of the problem of Eurocentrism also points to the divergent approaches to comparison taken up in both books. For van der Veer, comparison is “in the first place a question not of the right research design […] the ‘what’ and ‘how’ to compare” (as it is for Pollock and Elman), but rather “of an awareness of the conceptual difficulties in entering ‘other’ life worlds” (van der Veer Reference Van der Veer2016, p. 11). Van der Veer's comparative method pursues a “fragmentary approach,” in which “intensive study of a fragment is used to gain perspective on a larger whole,” and “allows us to ask questions about [that] larger whole” (pp. 9-11). Although most closely aligned with the priorities of anthropology, this “fragmentary approach” may hold insights for how to conduct comparison in other disciplinary contexts.

Similarly focused on the post-Opium Wars decades and extending into the mid-twentieth century, an edited volume entitled Beyond Pan-Asianism (2021) discusses the issue of pan-Asianism and the problems of using it as a framework to study this “period of vicissitudes.” By employing a variety of archival sources and “examining a wider cast of characters beyond the usual categories of political leaders and intellectual elites” (Sen and Tsui Reference Sen and Tsui2021, p. 9), the volume attempts to reconceptualize China-India connections and proposes alternative methods of pairing China and India by decentering the nation state, transcending the frameworks of pan-Asianism and of the so-called “Asia as method” (Chen Reference Chen2010), and questioning accepted norms of periodization based on political changes. The collection also demonstrates the ways in which some of the shortcomings of edited volumes could be addressed through prolonged collaborative research and interdisciplinary analysis.

Recent scholarship has focused on the late 1940s and 1950s period of exchange and collaboration between China and India conducted under the banner of cultural diplomacy. Research on the travels of cultural delegates, texts, materials, and knowledge across the Himalayas and against the backdrop of the early Cold War world has grown in part alongside the rise of Global South studies and its interest in discourses of the Third World, and in part from a desire to decenter the 1962 war, which often occupies center-stage in narratives of twentieth-century China-India relations (Ghosh Reference Ghosh2017). Particularly in the context of literary studies, attention to the lively interactions between writers, the new routes of publication and circulation, and the vibrant translation projects of the 1950s has proved vital for deepening our understanding of China-India literary connections beyond the sphere of Buddhism and that of Tagore's influence, two topics that previously dominated the field (Jia Reference Jia2019). As attention to discourses of solidarity grows, Adhira Mangalagiri has cautioned against too easy a valorization of state-sanctioned forms of “brotherhood” or “friendship” readily visible in records of China-India cultural diplomacy and, more broadly, in instances of South-South cultural exchange (Mangalagiri Reference Mangalagiri2019; Reference Mangalagiri2021a). China and India's engagements with ideas of the Third World (including China's more recent cultural engagements in Africa) may suggest at first glance a certain relation of horizontality, given the desire of South-South literary exchange to decenter the earlier mediating presence of colonial powers. However, Mangalagiri's scholarship calls for methodological vigilance to the frames of dominance that continue to organize such South-South exchange, including to the nation-states’ (often invisible) interventions in and packaging of those forms of “culture” deemed suitable for diplomacy (Mangalagiri Reference Mangalagiri2021b). This critical turn in 1950s China-India research mirrors a resonant development in Global South studies, in which an initial wave of scholarship “focused on discourses of solidarity made possible by the ‘mutual recognition’ of peoples’ shared conditions at the margins of global capital” while a newer “second wave […] works to complicate these dynamics of recognition” (Armillas-Tiseyra and Mahler Reference Armillas-Tiseyra and Mahler2021, p. 477). Attending to the unequal structures of power that made 1950s China-India cultural exchange possible can therefore compellingly extend this new direction in Global South studies.

The war of 1962 transformed the pairing of China and India in several ways. During the initial decades following the war, the armed conflict, territorial disputes, status of Tibet, and political relations between the two countries dominated academic and media discourse. Much of this writing has been one-sided and often influenced by the positions taken by the two states. In the late 1980s and 1990s, seemingly in response to the tense political relationship between China and India, scholars in the two countries revived some of the pan-Asian-style musings of the Buddhist connections with the aim of reestablishing cultural interactions mainly out of a nostalgia for the past. The framework of “civilizational” dialogue employed in these works adds little to understanding the complexities of earlier interactions but consists rather of reflections on how nostalgia also plays a role in the pairing of China and India. After about seven decades following the war of 1962, studies of the China-India border conflict have now become repetitive and speculative.Footnote 6 With each military flare-up on the border during the past few years, these ineffective analyses are rehashed and published in different forums. Such discourse remains popular primarily because of the commercial value that non-university presses, news outlets, and social media platforms attach to the topic. Identifying and analyzing new sources, investigating the impact of the war and border dispute on non-state actors, and examining the contacts that have continued among members of civil-society, despite the tensions between the two nations, rarely feature in publications.

The lack of access to new archival sources in China and India is usually cited as one of the reasons studies of the 1962 war and the border dispute have become repetitive. However, the fact that this hurdle can be overcome is evident from Bérénice Guyot-Réchard's (Reference Guyot-Réchard2017) Shadow States, which, using local archival sources, examines the anxieties and responses of various tribal groups living in the disputed border regions of northeast India to the conflict between the two nation states. Similarly, Sulmaan Wasif Khan's (Reference Khan2015) Muslim, Trader, Nomad, Spy, which focuses on the Tibetan frontier, employs documents from the now-restricted archives of the Foreign Ministry of the People's Republic of China. Also noteworthy is David G. Atwill's (Reference Atwill2018) Islamic Shangri-La, which describes the experiences of a group of Tibetan Muslims known as Khache and their search for an identity and homeland as relations between China and India deteriorated. A forthcoming study on Hindi literary engagements with ideas of China in the wake of war further demonstrates how 1962 may be better understood less as an abrupt end to China-India relations and more as a historical moment that generated new forms of imaginative engagement and transnational political being in the shadow of antagonistic bilateral relations (Mangalagiri Reference Mangalagiri2022).

The economic reforms instituted in China and India during the last quarter of the twentieth century brought some reprieve from the excessive focus on the border issue. Comparative studies of economic policies, developmental strategies, urban growth and disparities, and environmental concerns rapidly emerged as new arenas of research in the 2000s. However, some of these studies also illustrate the shortcoming of identifying proper variables for comparison and an absence of discussion on appropriate methodological tools pertaining to the pairing of China and India. This includes explaining, in the first place, the rationale for comparing China and India. Here, recent works by Selina Ho (Reference Ho2019), Mark Frazier (Reference Frazier2019), and Xuefei Ren (Reference Ren2020) have made significant contributions to methods of pairing China and India in a comparative perspective. All three have pointed out that comparisons of contemporary China and India cannot be framed within or explained through distinct types of regime, as in an authoritarian China and a democratic India. Perhaps the most important contribution to expand on this issue is Prasenjit Duara and Elizabeth J. Perry's (Reference Duara and Perry2018) edited volume Beyond Regimes. The editors propose the idea of “convergent comparison,” which, according to them, could investigate the parallels, both temporal and spatial, of China and India “at various critical junctures and at various levels of the political system, outside as well as inside the territorial confines of the nation-state” (Duara and Perry Reference Duara and Perry2018, p. 23). Duara and Perry also propose a new way of periodizing the pairing of China and India after the Second World War into three “temporalities”: “struggles of state- and nation-building,” “logic of citizenship and rights,” and “responses to globalization and neoliberalism.”

Two forthcoming books on twentieth-century literature continue this attempt to conceptualize the comparative and connective pairings of China-India. These two studies propose a rethinking of the pairing within wider frames of south-south relations and transnationalism, respectively. Imagining India in Modern China: Literary Decolonization and the Imperial Unconscious, 1895-1962 (Gvili Reference Gvili2022) examines the contours of a Chinese Global South imaginary, particularly a vision of a China-India solidarity that formed in the late Qing, reached a climax in the 1950s, and declined in the aftermath of the 1962 Sino-Indian war. Gal Gvili explores the Chinese turn to Indian literature, philosophy, and religions to envisage modern literature as an anticolonial project that often entailed a rejection of the West and the promotion of various ideals of the “East,” with China and India as its central axes. Given that most Chinese intellectuals access Indian ideas and texts via English-language translations and Orientalist scholarship, Gvili interrogates the promise of a south-south camaraderie and a decolonizing literary imagination that nevertheless remains intimately tied to colonial epistemologies and biases. The book studies the hopes, possibilities, and limitations of the “south-south” paradigm, which Gvili reframes as “south-north-south” in light of the shadow of English that loomed so substantially over the relationship. Attention to the mediation of relay or indirect translation, Gvili suggests, can open a window through which to interrogate the framework of the Global South and its tropes of friendship and solidarity.

While writers have often paired China and India together in expressions of solidarity, Adhira Mangalagiri's book approaches the China-India pairing from the opposite perspective. States of Disconnect: The China-India Literary Relation in the Twentieth Century (Mangalagiri Reference Mangalagiri2022) discusses Chinese and Hindi literatures (1900s-1960s) that engage in China-India thought, but that do so while calling into question the desirability or stability of the pairing. The book focuses on literary expressions of violence, silence, and distance between China and India, articulated against proclamations of China-India unity. Such texts index what Mangalagiri terms “disconnect,” defined not as simply the antonym of connection, but rather as a specific crisis of transnationalism perceptible in moments when one's ability to apprehend the transnational becomes severed or interrupted, or is rendered absent. The book develops critical strategies for apprehending disconnect, which have so far remained beyond the methodological frames of connectivity, mobility, and affinity that conventionally shape comparative literature. Texts of disconnect may appear antithetical to the forging of transnational relation, but when read as meditations on distinctly literary concerns, Mangalagiri shows how these literatures can in fact offer possibilities for building ethical relationships with national others when none seem readily at hand. Dwelling in the seeming ends of the China-India comparative unit, the book conceptualizes three reading practices – friction, ellipsis, and contingency – for an ethics of comparison that opposes both the hyper-connectivity of globalized paradigms and the insularity of the narrow nationalisms that are currently on the rise.

As the above discussion demonstrates, ways of pairing China and India varied with time, need, and circumstances. Sometimes such pairings were part of a polemical discourse, while at other times they stemmed from curiosity or even informed the self-reflection of those living in a third region. Academic scholarship on the pairing began in the first quarter of the twentieth century, and now this field of China-India studies has become a veritable publication industry unto itself. However, the question of how to pair China and India – and the interrogation of earlier framings, themes, and alternative periodizations – has only begun to be addressed recently. The essays in this issue are part of this undertaking, which attempts to reconceptualize and reformulate the pairing of China and India. They contribute to ongoing discussions of the methodologies needed to examine China and India through interconnected histories, differences and disentanglements, as well as shared challenges and diverse responses from multiple disciplinary perspectives.

In this Issue

The issue opens with two articles that re-examine a topic of enduring interest in China-India studies – the history and legacies of Buddhism – from the perspective of both new materials and original approaches. Jinah Kim's article, “China in Medieval Indian Imagination: ‘China’-inspired Images in Medieval South Asia,” challenges the diffusionist model that is prevalent in studies of Buddhism's spread across Asia. Such a model tends to foreground a unidirectional movement of materials and knowledge from Indian Buddhist centers to those in China, resulting in the treatment of India as a “remote, idealized, and ‘hollow’ center.” Kim undoes this center-periphery arrangement by examining instead instances of “multi-directionality” and “reverse travel back to the center.” The article focuses on Indian responses to Chinese Buddhists’ activities in India, and uncovers new evidence for iconography that may have been introduced to India through Chinese visitors. Kim suggests that, contrary to the prevalent conception of India as the quintessential Buddhist center, studying China in the medieval Indian imagination reveals how, after the demise of Buddhism in India, China itself came to be understood as “the ultimate Buddha land.” The article thus demonstrates the conceptual richness of treating “center” and “periphery” not as static sites but rather as dynamic conceptualizations of power that are constantly in a process of negotiation and remaking.

Similarly concerned with interrogating conventional centers of productive power, Jessica Zu examines twentieth-century Chinese and Indian Buddhist revivals that challenge colonial forms of universalism. The article “Three Plays and a Shared Socio-spiritual Horizon in Modern Buddhist Revivals in India and China” studies the retellings of a Buddhist story written and staged against Western formulations of equality and freedom, concepts that ironically underpinned colonial exploitation and yet often continue to be treated as universal values. In contrast, Zu shows how the Chinese and Indian revivalists explored “different forms of Buddhist social consciousness so as to stake out their own claims to universalism.” As such, they “subverted Europe's self-presentation as the modernizer by presenting ancient Indian and Chinese cultures as already modern.” The article reads the 1927 Peking opera Modengjia nü 摩登伽女 and Rabindranath Tagore's Chandalika (1933) in dialogue with each other and against Richard Wagner's unfinished “Buddhist” opera, Die Sieger. Zu's comparisons chart what she terms a “shared socio-spiritual horizon” as a creative China-India space in which alternative visions of an equitable society emerge through resonant engagements with Buddhist thought.

The issue then moves on to a pair of articles that discuss the China-India pairing vis-à-vis conceptualizations of Asia. In his article “Trans-Himalayan Science in Mid-twentieth Century China and India: Birbal Sahni, Hsü Jen, and a Pan-Asian Paleobotany,” Arunabh Ghosh discusses scientific collaboration between two paleobotanists who, through their research into fossilized plant life in the Himalayas, studied the very making of continental Asia geologically. In turn, Ghosh argues, Birbal Sahni and Hsü Jen (Xu Ren 徐仁) “offer new ways to think about Pan-Asianism” through their scientific activities: the circulation of their paleobotanic specimens, their joint evaluation of Continental Drift theory, and their pioneering work in forging scientific networks and institutions. Extending the early-twentieth century notion of Pan-Asianism, Ghosh suggests that, by posing challenges to nationalism and human-scale history, Hsü and Sahni's scientific work expands “how we might think about a practice of Pan-Asianism that was driven by research questions and centered on the circulation and exchange of knowledge, expertise, and scientific specimens.” Ghosh positions this history of China-India scientific knowledge production as an inter-Asian decentering of the West and of nationally bound frames in global histories of science.

Yasser Nasser's “Returning to ‘Asia’: Japanese Embraces of Sino-Indian Friendship, 1953–1962,” similarly explores the (re)making of “Asia,” but from the lens of political discourse in the wake of Japan's defeat in World War II. Through a multi-lingual and multi-archival approach, the article studies Japanese invocations of and reactions to ideas of China-India solidarity in the 1950s, following China and India's signing of the Panchsheel Treaty that declared the two states’ commitment to mutual friendship and learning. Nasser shows how a variety of Japanese actors, from the historian Uehara Senroku to the burakumin activist Jiichirō Matsumoto, looked to this Sino-Indian friendship as providing a new “vision of ‘Asian’ politics” that “prioritized cooperation and coexistence.” As such, it offered a pathway for Japan to break with its imperialist past while positioning itself in the emergent Cold War order. By examining China-India friendship from beyond their own borders, Nassar opens up a new line of inquiry that takes ‘“China-India’ as an analytic” and explores the various meanings and political ideals this discursive pairing held out for actors across Asia in the Cold War period.

The next set of articles experiments with new ways to track aesthetic circulations that open up spaces of convergence between China and India through entangled imaginaries, as well as shared narratives and adaptations. In her article “From The Good Earth to Mother India: Esthetic Circulations of Peasant Womanhood between India and China,” Anup Grewal offers what she terms the “rural/peasant/woman nexus” as a space of contested yet mirrored leftist political-aesthetic imaginations that link together a corpus of Chinese and Indian literary and cinematic texts. The article reads the figure of the peasant woman in Pearl Buck's The Good Earth, Katherine Mayo's Mother India, and Mehboob Khan's filmic re-stagings of these texts, alongside a collection of framing and formative “co-texts” by Lu Xun, Xiao Hong, and K.A. Abbas. Grewal argues that portraying the peasant woman proved key to imaginations of the nation in both China and India. Yet “the suturing of the rural, the peasant, and the woman into the space of the national narrative [remained] incomplete, even as different authoring discourses and imperatives attempt their smooth consolidation.” The article models a critical practice of apprehending politically resonant aesthetic vocabularies by attending to the ways in which texts can speak to each other through their intersecting movements within a shared temporality of socialist and anticolonial nationalisms.

Krista Van Fleit's article shifts to tracking the circulation of narratives between contemporary Chinese and Indian films in the increasingly intertwined Asian and global film markets. Her article, “Suspect Narratives: ‘Sinifying’ an ‘Indianized’ Japanese Story,” reveals a “cross-pollination” of repurposed, copied, and amended narratives in the Bollywood film Drishyam (2015) – arguably based upon a Japanese novel – and its Chinese adaptation, Sheep Without a Shepherd (wusha 误杀; 2019). Departing in its approach from both a “national cinemas” model and a fidelity-centered study of adaptation, the article unravels the complex entanglements of a crime story that is at once marked by transformative travels across Asia, and that uses intertextual filmic references to thematize its own global enmeshment. Van Fleit studies the “polylocality of cinematic space in Asia” by analyzing the changes in cultural referents and plot the films underwent in their quest to reach audiences in the Indian and Chinese film markets. By situating film production, technique, and tastes within the contexts of both national demands and global film culture, the article “complicate[s] understandings of what it means to make a film ‘Indian’ or ‘Chinese’.”

The issue concludes with a reflection upon the strategies of comparison that have emerged from a recent wave of publications in the field of China-India urban studies. Given the large urban populations and rapid urbanization underway in twenty-first century China and India, China-India urban studies has arisen as a field of increasing importance and interest. Mark Frazier's “The Challenges of China-India Comparative Urban Studies” surveys this new corpus of scholarship to discern four strategies of comparison: variation-seeking comparisons, encompassing comparisons, convergent comparisons, and temporal comparisons. Each marks an attempt to study urbanization in China and India on its own terms, without applying concepts rooted in the experience of Western cities, and also while avoiding the pitfalls of “methodological nationalism”. Frazier discusses the strengths and weaknesses of each strategy through an analysis of the “styles and scales of comparison” while also evaluating the ability of each strategy to capture national and local axes of analysis. The article's identification and assessment of comparative methods contains important interdisciplinary insights beyond its immediate focus on urban studies, and indeed beyond the cases of China and India.

Read as a whole, this issue showcases the conceptual vibrancy of China-India studies at the same time as it inaugurates a self-reflexive gesture. Each article actively contemplates the stakes and significance of China-India work by returning to the foundational questions of how to study China and India together responsibly, and why it is important to do so now. The issue opens up new lines of inquiry within China-India studies at the same time as it offers new conceptual pathways to other fields of research that seek similarly to surpass national borders, be it on the scales of the transnational, the global, the world, or the planet. As the work of decentering our disciplinary fields and methods continues, China-India studies can offer an exciting intellectual space in which to disrupt long-standing intellectual frames of dominance and to expose and grapple with the new forms of inequality currently on the rise.