INTRODUCTION

Prison reform efforts in developing countries are drawing attention to the improvement of offender treatment.Footnote 1 The topics related to prison reform have been often discussed in terms of offenders’ human rights, the environment of penal institutions and effective treatment of offenders. However, in addition to prison reform, it is important to consider the development and promotion of effective community corrections in the context of sustainable development of offender treatment. Building new penal institutions is not appropriate for sustainable development due to the negative influence and stigmatization of incarceration, including the negative impact on offenders’ life circumstances, its costs, the human rights of offenders and effectiveness for the prevention of recidivism (Someda Reference Someda2006:16–27). To some extent, building new penal institutions could, of course, be a solution to the overcrowding of penal institutions. However, when the prevention of recidivism is taken into account, recent research demonstrates the effectiveness of systematic cooperation between institutional and community corrections (Someda Reference Someda2006:10; Yoshida Reference Yoshida2014:118–19). In this context, the advantages of community corrections are emphasized.

Community corrections are the treatment of offenders outside jail or prison using various non-custodial measures in the community, and aim to reintegrate offenders into the community through various community resources and multi-agency cooperation. These offenders are serving court-imposed sentences either as an alternative to imprisonment (probation) or as conditional release from prison (parole). Some countries have parole authorities, such as the regional parole board in Japan, instead of the courts for the determination of conditional release from prison. The offenders must report regularly to their probation/parole officer and may have to participate in unpaid community work and rehabilitation programmes according to their probation/parole conditions. Consequently, the role of community corrections is to protect the safety of citizens in communities by providing viable alternatives to imprisonment and meaningful community supervision to offenders on probation, parole, or other forms of non-custodial supervision. For the sustainable development of society, it is important to focus on the positive impact that community corrections have on offenders by maintaining their connections to society.

Thus, it is important to add the concept of the development and promotion of community corrections to prison reform, and this concept will largely contribute to the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for Non-Custodial Measures (The Tokyo Rules), the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and other United Nations resolutions related to offender treatment policy.

The United Nations Asia and Far East Institute for the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders (UNAFEI)Footnote 2 has been supporting the development of criminal justice systems in developing countries for more than 50 years. In the field of community corrections, in particular, since February 2015, UNAFEI, in conjunction with the Department of Probation of the Ministry of Justice of Thailand and the Thailand Institute of Justice, has held the Seminar on Promoting Community-based Treatment in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Region for the 10 ASEAN member countries. These efforts continued through the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA)’s Third Country Training Programme for the Development of Effective Community-Based Treatment of Offenders in the CLMV Countries Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar and Vietnam (the CLMV countries), which was held in Thailand in February 2017.Footnote 3

The present article discusses the development of community corrections in the ASEAN countries from the perspective of UNAFEI’s technical assistance and analyses the status of imprisonment and community corrections in the region, particularly in terms of the sustainable development of offender treatment in this region.

CURRENT STATUS AND CHALLENGES OF OFFENDER TREATMENT IN THE ASEAN REGION AS AN EXAMPLE OF IMPLEMENTATION OF THE 2030 AGENDA FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

Overview of ASEAN

ASEAN, a regional organization established in 1976, consists of 10 countries in Southeast Asia: Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. As of 2015, ASEAN’s population is the third largest in the world, and its average annual economic growth rate of 5.2% between 2007 and 2015 is the sixth largest in the world (ASEAN 2016).

Mobility of persons has been quite active based on the formal establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community in December 2015. Although its economic growth is astonishing, the region faces challenges resulting from globalization, urbanization and development. Almost all problems indicated in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development are applicable in ASEAN, and problems in criminal justice systems, such as high prison population rates, drug crime, and so on, are inseparable from the sustainable development of ASEAN.

Current Status and Challenges of Offender Treatment in the ASEAN Region

Prisons have been widely used as the traditional form of punishment all over the world. Prison populations around the world are increasing,Footnote 4 which has led to prison overcrowding. This is a common problem in many countries (Institute for Criminal Policy Research 2016a). While Japan, for the time, has overcome the problem of prison overcrowding, most ASEAN countries still suffer from prison overcrowding and a high prison population rate. On the other hand, community corrections and non-custodial measures are widely implemented as effective measures for offender rehabilitation in developed countries. They have long been recognized as more advantageous than imprisonment in terms of cost-effectiveness, humanitarianism and effective reintegration of offenders into society. In the ASEAN region, some countries such as Thailand, the Philippines and Singapore have already utilized community corrections as a part of measures for offender treatment, although the Philippines and Thailand are still suffering from high prison population rates and prison overcrowding. However, other countries, namely Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar and Vietnam (the CLMV countries), are still attempting to establish community corrections as a part of their criminal justice systems. Although these countries have legislation on community corrections, they have not yet implemented efficient community corrections and non-custodial measures, and some may lack a national organization to implement the system.

Lack of implementation of community corrections implies that states heavily rely on imprisonment as the principal punishment, which is costly and causes stigma and other negative impacts on offenders. Meanwhile, community corrections offer a more humanitarian approach and individual treatment for offenders, especially for those who have not committed serious crimes. Offenders under community corrections can be rehabilitated while they are in the community with their families and are able to work to earn their own livings. When community corrections are applied, states can gain greater benefits from their own people and spend less than they would confining people in prisons.

Since UNAFEI and the Thai government jointly implemented the ASEAN Seminars for the Promotion of Community-Based Treatment of Offenders in 2015, the member countries have discussed how to promote and develop community corrections and have identified the issues that are preventing the implementation of community-based treatment of offenders. The member countries confirmed at the ASEAN seminars that some countries such as the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand have established and are implementing community corrections while the CLMV countries have not yet implemented it effectively. This situation is in line with the Roadmap for ASEAN Plus Three Probation and Non-Custodial Measures Cooperation (Table 1), which was agreed during the Second ASEAN Plus Three Conference on Probation and Non-Custodial Measures held in Thailand in August 2014. The Roadmap aims to accelerate the promotion of community corrections and to help member countries to reduce the disparity in the application of community corrections in the region.

Table 1 Roadmap for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Plus Three Probation and Non-Custodial Measures Cooperation

Hence, the development of community corrections is needed in the CLMV countries. This will enhance the economic and social growth of the ASEAN community and promote regional sustainable development through fair and just systems of offender treatment.

Status of Imprisonment and Community Corrections in the ASEAN Region

UNAFEI’s mission is to provide technical assistance based on studies and research in targeting countries and regions. UNAFEI faculty members have collected information to enhance the effectiveness of technical assistance through country presentations at UNAFEI’s international training courses, seminars, international conferences, and so on. At the same time, they use open resources such as criminal justice statistics. For example, crime trends, data on prison overcrowding, prison population rates, etc. are very useful sources for understanding the status of targeted countries and regions.

When UNAFEI considered offering technical assistance for the promotion of community corrections in the ASEAN countries, it was important to analyse the status of offender treatment in the region. Many ASEAN countries are suffering from prison overcrowdingFootnote 5 and high prison population rates. Table 2 shows those data on the status of incarceration and social conditions in the ASEAN Plus Three countries.Footnote 6 Regarding prison occupancy, all countries except Malaysia exceed 100% capacity. Lao PDR and Vietnam do not have sufficient data on this issue. Many ASEAN countries record relatively high prison population rates.

Table 2 Status of Incarceration and Social Conditions in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Plus Three Countries

When the status of community corrections is considered at the same time as the status of incarceration, the situation in the region is clearer. Figure 1 shows the status of the implementation of non-custodial measures and community corrections in ASEAN. In Figure 1, it seems that many ASEAN countries widely implement the non-custodial measures. However, the CLMV countries and some others reported that they do not actually implement those measures in practice despite having legislation on non-custodial measures. In addition, multi-agency and inter-agency approaches among criminal justice agencies, social welfare services, medical institutions, and so on do not function in those countries because there are few practical opportunities to cooperate in the field of offender treatment.

Figure 1 Status of the implementation of non-custodial measures and community corrections in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Plus Three countries. For a colour figure, see the online version of the article Source: Based on the research for the Second Seminar on Promoting Community-Based Treatment in the ASEAN Region, which was held by the United Nations Asia and Far East Institute for the Prevention and Crime and the Treatment of Offenders (UNAFEI), the Department of Probation of the Ministry of Justice of Thailand, and the Thailand Institute of Justice from 2 to 4 March 2016 in Thailand.

The main reasons why many of the ASEAN countries suffer from high prison population rates and high prison occupancy levels are not only lack of implementation of community corrections but also lack of appropriate assessment of offenders, particularly for vulnerable offenders who need to rely on welfare services instead of incarceration. In addition, the capacity of social welfare services is probably insufficient compared with the number of offenders. This problem is illustrated by the high prison population rate of drug-dependent offenders, who should be treated in community-based settings but cannot be treated there because of lack of resources in the community. It is a serious issue among several Southeast Asian countries where drug-related offences continue to rise and account for about 60% of the prison population, resulting in prison overcrowding and burdens on the criminal justice system. For example, this is the case in Lao PDR (Thailand Institute of Justice 2016:47–51). Those who suffer from drug dependence are often treated in the criminal justice system, but it should be a health issue rather than a criminal justice issue. Scientific research has also shown that effective treatment for drug use has helped drug-dependent individuals to halt their consumption, prevent relapse, reduce their involvement in crime and make a positive contribution to their family and community, thus reducing recidivism for drug-related offences and the burden on overcrowded prisons (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2015:33). In terms of reducing the number of incarcerated drug offenders, it is necessary to focus on their community-based treatment in cooperation with medical and welfare services. Of course, it should not be ignored that one of the causes of the high population of drug offenders in prisons in Southeast Asia is that they often commit other crimes, such as murder, violence, burglary, theft, and so on, when under the influence of drugs (Penal Reform International 2015:14). Since the recidivism rate for drug-related offences is high and drug use and dependence affect offenders’ mental and physical health, long-term and sustained medical care and other necessary interventions by multiple agencies are required (National Institute of Drug Abuse 2014). Therefore, the ASEAN countries require technical assistance which focuses on effective community corrections.

As a result of the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community at the end of 2015, the movement of persons and economic activity in the region have been facilitated. At the same time, it must be noted that the movement of persons also includes offenders involved in community corrections (Burdeos Reference Burdeos2015; Ong Reference Ong2015). While the European Union (EU) countries have already established a system to supervise offenders in the community wherever they come from in the region, each country in the ASEAN region implements neither the common concepts of community corrections nor the same or similar legislation on community corrections. The Philippines, which sees many of its workers emigrate to other countries, pays particular attention to effective international cooperation in community corrections (Burdeos Reference Burdeos2015). Therefore, the Philippines, at the Third ASEAN Plus Three Forum on Probation and Community-Based Rehabilitation, proposed the establishment of the ASEAN Plus Three Probation Association. Based on the discussion above mentioned, UNAFEI has continued to provide technical assistance in the field of community corrections to developing countries.

Imprisonment and Social Condition in the ASEAN Region

In the process of considering the contents of technical assistance for the ASEAN countries, UNAFEI and participating ASEAN countries shared good practices and statistical information, and analysed existing criminological and penological studies. For example, the study considering the relationship between social conditions and incarceration conducted by Tapio Lappi-Seppälä of the National Research Institute of Legal Policy in FinlandFootnote 7 provides important perspectives which apply to the ASEAN countries’ consideration of effective offender treatment systems (Lappi-Seppälä 2008:93–120). According to his study in Europe, there is a correlation between incarceration and social fairness and between incarceration and social welfare services. Those correlations are analysed by the relationship between a country’s prison population rate and its Gini index, which indicates an aspect of social fairness in a country, and the relationship between the prison population rate and the proportion of the health and medical expenditure to the total government expenditure. Social fairness is significantly related to the level of social welfare services in each country. In addition, if such services are substantial, the risk of crime will be reduced by social welfare policies. For example, it may be better to connect offenders who are disabled or elderly with welfare services instead of forcing them to go to prisons for their treatment.

Those views are significantly related to the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its Goals. For example, Goal 10 requires reducing inequality within and among countries while Goal 16 aims to promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels. It is important and helpful for understanding social conditions and incarceration to consider the relationship between social fairness and offender treatment in terms of the sustainable development of the region.

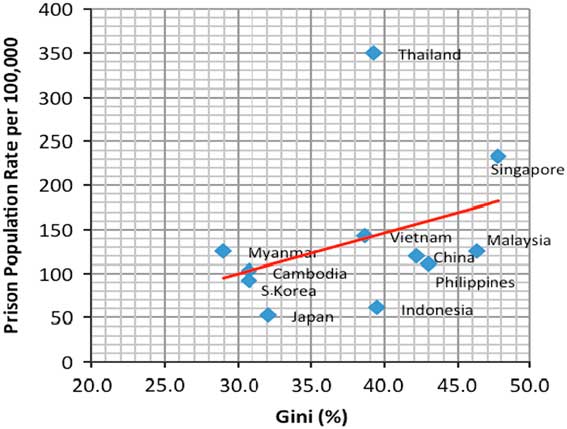

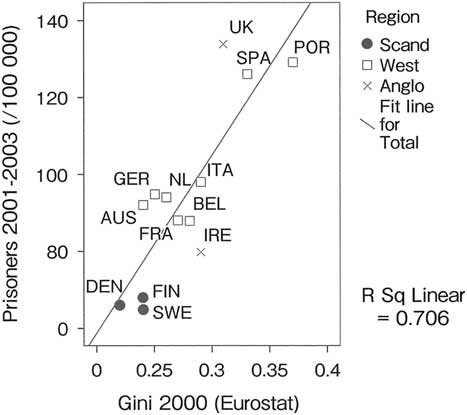

Figure 2 shows the correlation between Gini index rates and prison population rates in the ASEAN Plus Three countries. As seen in Figure 3 for Europe, which was created by Lappi-Seppälä (2008:102), the regression line in this graph indicates that the countries with less social fairness tend to have higher prison population rates in Asian countries.

Figure 2 Correlation between incarceration and social fairness in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Plus Three countries. For a colour figure, see the online version of the article Source: Based on the World Prison Brief (Institute for Criminal Policy Research 2016a), the World Bank (2016b) and the CIA (2016).

Figure 3 Gini index and prisoner rates 2000 in Europe. This figure refers to the Scandinavian (Scand) countries (three countries; Denmark, Finland and Sweden), the Western European (West) countries (eight countries; Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain) and the Anglo-Saxon (Anglo) countries (two countries; the UK and Republic of Ireland) Source: Lappi-Seppälä (2008:102).

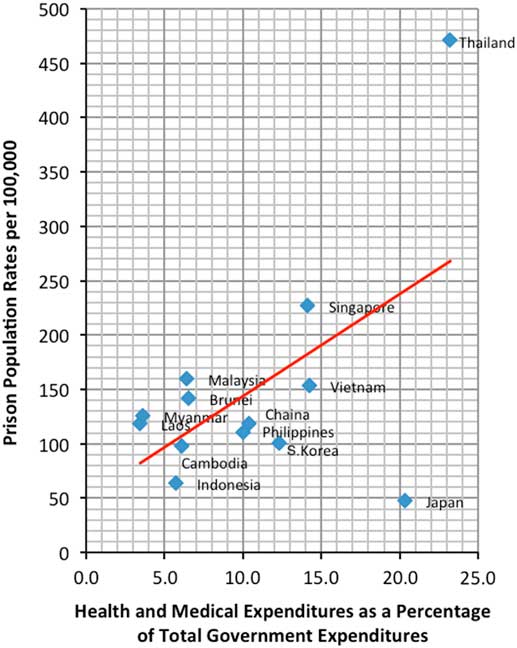

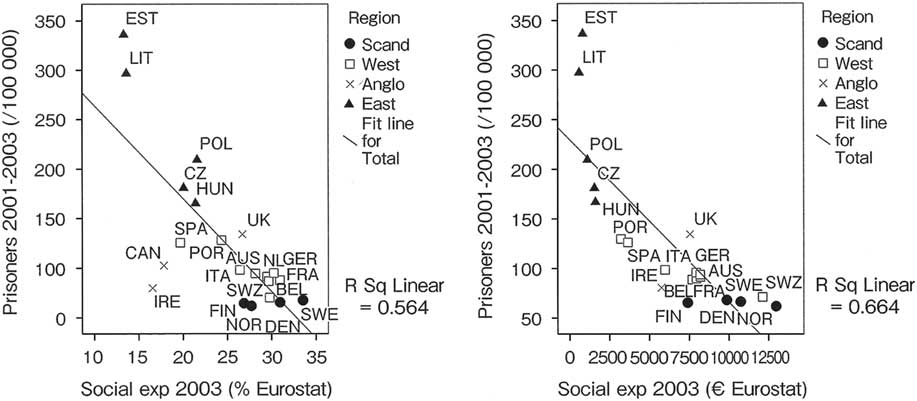

On the other hand, Figure 4 shows the relationship between the prison population rate and social welfare services in the ASEAN Plus Three countries. In this graph, the trend line is upward sloping, which suggests a counterintuitive result from the study in Europe and Canada as seen in Figure 5; that is, spending more money on social welfare services will actually increase the prison population rate. In order to understand this result, we must draw attention to the differences of proportion of health and medical expenditures to the total government expenditures between EU and ASEAN countries. While the proportion in the EU is about 16% in 2014, the proportion in ASEAN countries is lower: Brunei Darussalam 6.5%, Indonesia 5.7%, Cambodia 6.1%, Lao PDR 3.4%, Myanmar 3.5%, Malaysia 6.4%, Philippines 10%, Singapore 14%, and Vietnam 14.2%. Only Thailand had a higher proportion at 23.2% (World Bank 2016a). It seems that the social welfare services in many ASEAN countries are not yet prepared to provide treatment to offenders in cooperation with criminal justice agencies.

Figure 4 Correlation between incarceration and social welfare services in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Plus Three countries. For a colour figure, see the online version of the article Source: Based on the World Prison Brief (Institute for Criminal Policy Research 2016a), the World Bank (2016a) and the CIA (2016).

Figure 5 Social expenditures and prisoner rates in Europe and Canada. These figures refer to the Scandinavian (Scand) countries (four countries; Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden), the Western European (West) countries (nine countries; Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Switzerland), the Anglo-Saxon (Anglo) countries (three countries; Canada, the UK and Republic of Ireland) and the East European (East) Countries (five countries; Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania and Poland) Source: Lappi-Seppälä (2008:102).

Implications from Japanese Experience

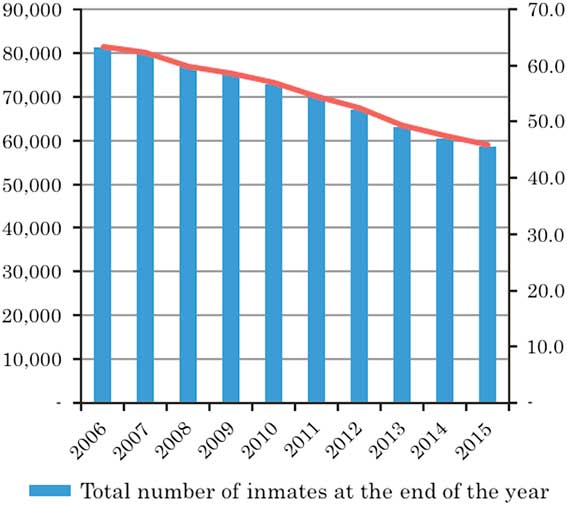

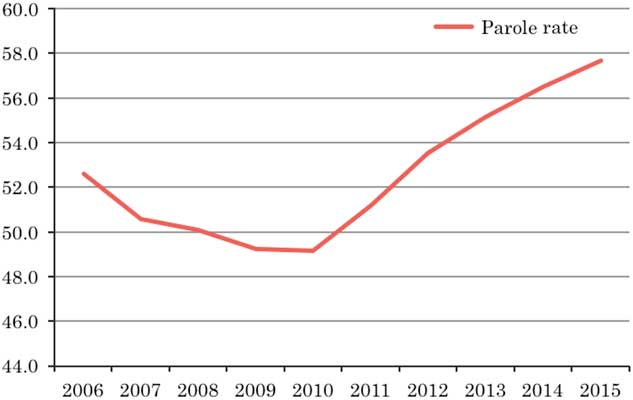

Japan, for the time being, has overcome the problem of prison overcrowding by implementing various non-custodial measures as well as effective crime prevention efforts. Although it is difficult to determine that non-custodial measures are a single solution to reduce the prison population, much research has cited the benefits of non-custodial measures (Someda Reference Someda2006:16–27; Lappi-Seppälä 2008:101–4). In fact, Japan has been reducing the prison population rate for 10 years since 2006 (Figure 6). Although this reduction is significant because of the reduction in the number of crimes reported to the police, it seems that implementing non-custodial measures has also contributed to the reduction of the prison population. For example, the parole rate has increased gradually since 2010 (Figure 7), and it correlates with the reduction of the prison population rate.

Figure 6 Year-end inmate population of penal institutions and rate per 100,000 population. For a colour figure, see the online version of the article Source: Research and Training Institute, Ministry of Justice, Japan (2016:48).

Figure 7 Parole rate. For a colour figure, see the online version of the article Source: Research and Training Institute, Ministry of Justice, Japan (2016:65).

One of the reasons why it is possible for Japan to implement non-custodial measures such as parole supervision is that a networking system between criminal justice agencies and social welfare agencies is working effectively at the community level. In addition, Japan spends more money on social welfare compared with the ASEAN countries.Footnote 8

In fact, various measures to promote vulnerable offenders’ reintegration into society have been implemented in Japan. One of the significant measures to reduce imprisonment of low-risk vulnerable offenders is the Japanese practice of “special coordination of social circumstances” for elderly and disabled offenders (hereinafter referred to as “Special Coordination”), which was established in 2009.Footnote 9 Coordination of social circumstances for inmates usually is conducted by volunteer probation officers in the community under the direction of probation officers. This practice, which is a part of the coordination of social circumstances for inmates, aims to encourage released inmates who suffer difficulties in self-reliance due to old age or disability to achieve smoother reintegration into society. This is an example of the effective implementation of parole as a non-custodial measure within the framework of urgent aftercare of discharged offenders. Under this system, probation officers and volunteer probation officers work with correctional institutions or prefectural Community Settlement Support Centres established by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare to provide inmates with the necessary coordination services so that they will be able to make use of welfare services available from local governments or social welfare corporations immediately after release from a correctional institution. In this process, multi-agency coordination often utilizes the official networks of public agencies and information and networks brought by volunteer probation officers.

Since the Community Settlement Support Centres are familiar with welfare assistance and its procedure, they can make arrangements to solve the inmates’ problems and maintain the necessary assistance. Actually, before Special Coordination was established, the inmates had been released from correctional institutions without welfare assistance after the termination of sentence, even if they were elderly or disabled and without housing. However, after Special Coordination was established, housing and welfare services – which are important factors for the prevention of recidivism – have been provided for these offenders after release.

This new policy is a typical example of multi-agency cooperation, which significantly contributes to the reduction of the prison population and effectively functions as a measure for the prevention of recidivism in Japan.Footnote 10 By encouraging multi-agency cooperation at the community level, the government of Japan provides volunteer probation officers with the tools they need to successfully coordinate offenders’ return to the community.

A Model of Offender Treatment Considering Social and Cultural Context

Most ASEAN countries have relatively higher prison population rates than in the ASEAN Plus Three countries and lack the necessary social welfare policies for vulnerable offenders. The exception is Thailand, which has higher social welfare expenditures. However, it also has a high prison population rate due to drug-related offenders that exceed the capacity of the social welfare system. This is despite the fact that Thailand spends more than 20% of its total government expenditure on health and medical care. Thus, the situation in Thailand indicates that its health and medical care policies still have not caught up with the growth in the number of drug offenders generated by the “war on drugs” conducted by the former Prime Minister Thaksin’s administration since 2003 (Fernquest Reference Fernquest2016).Footnote 11

ASEAN countries are relatively similar to JapanFootnote 12 in terms of culture, and therefore, the local communities in the region might have the potential to prevent recidivism by community cohesion, which is represented by community volunteers or other organizations rooted in the community, through multi-agency cooperation supported by local authorities.Footnote 13 Although these societies confront conditions of rapid modernization, it seems that community empowerment remains an effective offender treatment measure in those countries, if the government assists and encourages multi-agency cooperation. This assumption seems to be proven by the Japanese experience, which underwent rapid modernization decades earlier than the ASEAN region. In fact, this cultural similarity has contributed to the development of the Volunteer Probation Officers systems in the Philippines and Thailand, which were supported by UNAFEI.Footnote 14 The consideration of the cultural background of each country is always an important factor for the successful development and implementation of new policies.

PROMOTION OF SUSTAINABLE OFFENDER TREATMENT THROUGH COMMUNITY CORRECTIONS

Although the figures shown in the previous section imply that a certain relationship was found between social fairness, social welfare services and incarceration, income inequality and social disparity in Asian countries are still larger than those of European countries and social conditions are still being developed. However, as the European study indicates, the welfare approach towards offenders who need assistance increases the effectiveness of non-custodial measures. Thus, the welfare model is necessary for the treatment of offenders in the ASEAN countries.

When discussing alternatives to imprisonment, there is always a question of the net-widening effect, that is, whether the role of non-custodial measures can replace imprisonment or whether non-custodial measures just function as a penalty for new groups of offenders (Albrecht Reference Albrecht2010:44; Doi Reference Doi2012:15). Indeed, the Commentary on the Tokyo Rules, which is one of the most significant references for policy makers and practitioners of offender treatment, points out that:

Despite the obvious advantage of non-custodial measures, reforms intended to promote the use of such measures contain potential dangers and may lead to unintended consequences. For example, the use of non-custodial measures may be increased, not at the expense of imprisonment but at the expense of other less onerous penalties. This may lead to an increase in the total use of penal measures in society, an increase that cannot be justified by a reference to a worsened crime situation. At the same time, there may be no reduction in the use of imprisonment. This has been termed the net-widening effect.

Another possible danger is that new non-custodial measures may be introduced that impose more intensive forms of control. Instead of replacing imprisonment, they may replace non-custodial penalties that involve less control. More intrusive control than the circumstances warrant may thus be introduced. Ways of identifying and avoiding these disadvantages can be found in the Tokyo Rules.

(United Nations 1993:7)

In Japan, the implementation of certain non-custodial measures, as well as the decline of reported cases, has contributed to the reduction of the prison population since 2006. However, a tougher approach to crime is still discussed whenever serious crimes are committed. The policies based on the tough-on-crime approach, often called “penal populism”, have overemphasized criminal punishment without considering offender rehabilitation. For example, in Japanese society, it is often difficult to benefit from the social welfare service once someone becomes involved with the criminal justice system as a criminal. Once labelled as criminals, these persons tend to be isolated from society. Consequently, “penal populism” gives rise to social exclusion. In order to remedy this situation, Japan has implemented various measures to promote vulnerable offenders’ reintegration into society, as mentioned above, although their effect is still limited. Thus, in Japan, offender treatment is about to shift toward the social inclusion approach according to the policy adopted by the government (Cabinet Office 2012, 2014).Footnote 15

Considering the development of community corrections in the ASEAN region, the discussion of the net-widening effect in offender treatment is important. While important in all ASEAN countries, which lack sufficient statistical data, this is particularly true in the CLMV countries, which are all attempting to establish community corrections systems. Although not a CLMV country, the situation in Thailand from 2003 to 2014 demonstrates the net-widening effect and “penal populism”, which resulted from the government’s tough-on-crime approach. The increase in the number of crimes and the number of offenders treated in the Thai criminal justice system until 2014 resulted from the government’s policies, which were represented characterized as the “war on drugs” policy (Fernquest Reference Fernquest2016). Since that policy was imposed, the prison population in Thailand had increased year by year until 2014, but it has decreased slightly since then.Footnote 16 Nevertheless, the prison population remains high. Following the same trend, the number of probation casesFootnote 17 and the identification of drug users and the drug rehabilitation cases based on the Narcotic Addiction Rehabilitation Act 2002Footnote 18 all peaked around 2013 or 2014 and have subsequently declined. Those data, which show the trend of the treatment of offenders, follow the same trend as the number of persons arrested,Footnote 19 as well as the recidivism rate, which is defined as reoffending within three years after termination of probation.Footnote 20 Those trends show that the government crime control policies significantly affected the scale of offender treatment, although the reasons those numbers began to decline around 2014 are unclear.

Comparing the trends between imprisonment and community corrections from 2002 to 2016 in Thailand – when the government pursued a tough-on-crime approach – it seems that the implementation of non-custodial measures contributed to neither the reduction of the prison population nor the recidivism rate.

After comparison between Japan’s social inclusion approach and Thailand’s tough-on-crime approach, it seems likely that the social inclusion approach can be effective through the implementation of community corrections; however, policies based on the “penal populism” would undermine this crime control strategy. Although further statistical analysis still needs to be done, based on the discussion of cultural background in community corrections through the Japanese experience mentioned above, the combination of criminal justice policies and social welfare measures might be effective particularly for vulnerable offenders, and might significantly contribute to the reduction of prison populations in the ASEAN region.

Thus, it is important to consider how many prisoners need welfare services instead of imprisonment. To determine this number, the assessment of the offender and social investigations such as pre-trial investigation and parole examination are very important. At the same time, criminal justice practitioners are responsible for public safety. Therefore, it is important that offenders are appropriately placed either in prisons or in society based on their needs and the risks of recidivism.

CONCLUSION

The present article has discussed the development of community corrections in the ASEAN region by analysing the socio-economic status of the region and referring to the technical assistance provided by the Japanese government and UNAFEI. One of the problems of the net-widening effect in offender treatment is often related to “penal populism”, which leads to tougher penalties for offenders, and it increases the prison population in some countries. However, criminal justice practitioners know that imprisonment is not a single solution to preventing recidivism and creating safer societies. In terms of sustainable and effective offender treatment, it is necessary to promote public understanding of the fact that community corrections play a key role in offender treatment as a result of the statistical analysis of imprisonment and socio-economic status. Consequently, it is important that the general public in the ASEAN region, as well as all stakeholders such as policy makers, practitioners, academics and practitioners, share the concept of community corrections as a new effective policy to protect society.

Satoshi Minoura is a professor at the United Nations Asia and Far East Institute for the Prevention and Crime and the Treatment of Offenders (UNAFEI). He was assigned to UNAFEI in April 2015, prior to which he had been working as a probation officer in the Tokyo Probation Office and as the chief of the legal and general affairs sections of the Rehabilitation Bureau in the Ministry of Justice, Japan.