INTRODUCTION

Child homicide, the most serious form of violence against children, is widespread in contemporary societies. A study released by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in 2019 suggests that, between 2008 and 2017, an estimated total of 205,153 children aged 0 to 14 years were intentionally killed worldwide; and over the same period, an estimated total of 1.7 million adolescents and young adults between the ages of 15 and 29 were murdered. The study further indicates that in 2017 alone, about 21,540 children aged 0 to 14 years and 182,778 adolescents and young adults aged 15 to 29 years fell victim to homicidal violence (UNODC 2019). A report released by the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) in 2014 also discloses that approximately 95,000 young people below 20 years are murdered each year globally (UNICEF 2014).

It has been suggested by various studies and reports that the majority of child homicide victims (about 90%) live in low-income and middle-income countries such as those in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America (Krug et al. Reference Krug, Dahlberg, Mercy, Zwi and Lozano2002; Pinheiro Reference Pinheiro2006; Stöckl et al. Reference Stöckl, Dekel, Morris-Gehring, Watts and Abrahams2017; UNICEF 2014). According to Shanaaz Mathews et al. (Reference Mathews, Abrahams, Jewkes, Martin and Lombard2013) and Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro (Reference Pinheiro2006), the estimated rate of child homicide in Africa is 5.6 per 100,000 children under the age of 18 years; and this figure is double the estimated global rate of 2.4 per 100,000 children under 18 years of age. Lethal violence against children “can take many forms and is influenced by a wide range of factors, such as the personal characteristics of the victim and perpetrator and their cultural and physical environments” as well as their beliefs (UNODC 2019:8). One form of child homicide that is almost completely ignored in the literature, and on which the present study focuses attention, is ritual paedicide, a phrase coined by the present author to denote the killing of children aged 0 to 17 years for ritual or occult purposes. Ritual paedicide generally involves harvesting the victims’ body parts and/or the draining of blood. However, body parts and blood may not be extracted in some instances, particularly if the prescribed ritual only requires perpetrators to have sexual intercourse with victims.

Indeed, a substantial proportion of child homicides in Africa results from certain superstitions, particularly juju/occult beliefs (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005; Cimpric Reference Cimpric2010; Igbinovia Reference Igbinovia1988). Yet, ritual paedicide or juju-triggered child homicide in Africa has received virtually no attention in the academic literature. Most of the sparse extant studies on the general subject of ritual murder (e.g. Evans Reference Evans1993; Gocking Reference Gocking2000; Nuamah Reference Nuamah1985; Pratten Reference Pratten1998, Reference Pratten2007; Rathbone Reference Rathbone1993) only offer historical perspectives rather than criminological analysis of the subject. However, as Mensah Adinkrah rightly mentions, “it is important to frame discussions of ritual homicide as a crime rather than mere spectacle in societies where it occurs” (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005:32). Besides, there is presently a lack of data on the prevalence of ritual paedicide and, consequently, a lack of effective and realistic prevention and protection programmes or mechanisms. Therefore, it is important that systematic and critical analysis of the impact of belief in juju on homicides in general, and paedicides in particular, in Africa is carried out by social and behavioural scientists.

To fill the huge literature gap, the present study establishes the scale and identifies the principal features, motivations, and socio-cultural, religious and economic contexts of ritual paedicide in contemporary Ghana. The study also examines the criminal justice system’s responses to such murders and explores appropriate measures that could be taken to combat the horrendous phenomenon. The first part of the study attempts an explanation of the concept of juju and explores the historical development of juju-driven homicide in Africa. The second part offers a cursory overview of the scale of the juju belief and its associated violence against children in Ghana. Part three then briefly describes the main method/approach employed to gather data for determining the magnitude, features, and socio-cultural and economic contexts of ritual paedicide in the country, identifying key ethical issues. The fourth part presents an in-depth analysis of ritual murder cases/reports published on the websites of three renowned local Ghanaian media outlets between September 2013 and August 2020. Part five critically discusses the results, taking into account the views of 20 academics, experts, heads of relevant governmental and non-governmental bodies, traditional leaders, and other relevant members of the public who were interviewed. It also examines the criminal justice system’s effectiveness in responding to ritual paedicide in Ghana. The final part proposes appropriate and practical steps that could be taken to address the problem.

JUJU AND RITUAL MURDER IN AFRICA

Understanding the Concept of Juju

It has been suggested by some writers that the term “juju” is derived from the French word joujou, meaning “plaything”, “toy” or “play-object” (Changa Reference Changa, Asante and Mazama2009; Zivkovic Reference Zivkovic2017). This has been contested by others who believe that it is a Hausa word for “fetish” or “evil spirit” (see Changa Reference Changa2017). However, it is almost indisputable that juju “stems from the spiritual belief system emanating from West African countries such as Nigeria, Benin, Togo, and Ghana, although its assumptions are shared by … [many other] African people” or communities (Changa Reference Changa, Asante and Mazama2009:355; see also Neal Reference Neal1966; Ojo Reference Ojo1981). The term juju, which is often employed as a synonym for black magic, occultism, and even voodoo, denotes a variety of concepts (Fellows Reference Fellows2010; Max-Wirth Reference Max-Wirth2016; Neal Reference Neal1966; Sarpong Reference Sarpong2002). It may refer to the act of using incantations or objects to harm or help people psychically or to control events; it can denote an object that has been purposely infused with supernatural power or magical properties such as a talisman, amulet, protective ring, etc.; and it may refer to a supernatural power attributed to a charm or fetish (Changa Reference Changa, Asante and Mazama2009; Neal Reference Neal1966; Ojo Reference Ojo1981; Sarpong Reference Sarpong2002).

Juju, according to several academics and experts, generally describes the popular African belief that incantations and/or certain objects such as eggs, cowries, garments, leaves/plants, animals, or human blood and body parts can be used as part of rituals to manipulate events in life and to alter the destiny of people either from bad to good or vice versa (Fellows Reference Fellows2010; Ojo Reference Ojo1981; Owusu Reference Owusu2019). Simply put, juju is the African belief system and religious practice involving the use of objects and/or words to psychically manipulate events or alter people’s destiny positively or negatively. Juju rites are usually performed by specialists who may be called different names in different communities in Africa. However, diviners, soothsayers, sorcerers, occult capos, traditional healers, etc., could all be classified as juju specialists (Owusu Reference Owusu2019).

Even though several objects, as already indicated, can be used for juju practices, human blood and body parts seem to have become some of the frequently used ingredients or things for such rituals in contemporary Africa (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005; Labuschagne Reference Labuschagne2004; Lyncaster Reference Lyncaster2014; Owusu Reference Owusu2019). Thus, there is a systemic belief throughout the region, regardless of tribe or country, that using human blood and body parts for a ritual can bring good luck, guarantee prosperity, ensure protection against diseases or misfortunes and enhance social life. This unfounded conception has triggered an increase in violent crimes, including murder, committed by people seeking the instant realization of their dreams and ambitions (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005, Reference Adinkrah2017; Changa Reference Changa, Asante and Mazama2009; Nickerson Reference Nickerson2013; Owusu Reference Owusu2019; Ross Reference Ross2008). Juju practitioners are widely consulted on the continent for various reasons. They are the ones who usually recommend medicines with human ingredients, specify the body parts required, and prepare the supposedly potent potion.

The juju-related testimony of James Neal, a British settler who served as Chief Investigations Officer in Ghana (formerly known as the Gold Coast) between 1952 and 1962, is worth mentioning here. Neal (Reference Neal1966) recounts an instance where a comparatively small tree that could not be uprooted even with bulldozers and other mechanical means was easily pulled down with a rope by a few people following the performance of a ritual involving the slaughtering of three sheep, the pouring of libation with three bottles of liquor, and chants by a fetish priest. Describing how the ceremony was performed, he writes:

The Fetish Priest killed the animals by cutting their throats in a ceremonial manner and then letting their blood trickle into the ground at the bottom of the tree. This done, he poured some of the gin around the base of the tree as a libation to the spirit [believed to be inhabiting the tree], and then entered into a semi-trance, talking in a chanting voice to the invisible spirit in the tree …. He then poured out more gin around the tree and performed certain rituals. (Neal Reference Neal1966:22–3)

Neal (Reference Neal1966) also narrates how two strong and fit individuals who agreed to give evidence against a man facing extortion charges mysteriously died a few days after the accused person had threatened to kill them with juju if they persisted with their intention of appearing as witnesses for the prosecution. After numerous adjournments, the accused was eventually convicted and sentenced to two years’ imprisonment; but he did not leave the courtroom without threatening to deal with Neal in the spiritual realm ruthlessly. Approximately a week after this episode, Neal began to suffer a series of prolonged serious illnesses, each of which vanished immediately after a powerful juju-man had been invited to perform rituals in his house to counteract the harmful effect of juju spells believed to have been the cause of his troubles (Neal Reference Neal1966). He also describes an instance where the potency of a harmful black juju powder that had been placed on the seat of his vehicle, apparently to harm him, was spectacularly rendered impotent after it came into contact with a protective amulet that had been given to him by a powerful juju-man. He explains the mysterious spectacle that occurred in the following words:

I unlocked the [car] door and placed my amulet on to the black powder covering the whole of the seat. I hardly believed my eyes when I saw the black Ju-ju powder turned grey almost immediately, and a moment later into what looked like ash of burned paper, which was almost instantly blown away by the very slight breeze. (Neal Reference Neal1966:95)

He again narrates a mysterious, horrific accident he had at an event the day he forgot to carry his protective amulet along with him. Unable to bear any longer the dangerous threats that juju posed to his life daily, he reluctantly left the shores of Ghana after 10 years of living and working in the country. After reflecting on all his terrifying experiences and adventures in “juju-ridden” Ghana, Neal makes the following interesting conclusion:

Whatever the answers may be, whatever theories may be put forward, all I know is that in ten years in Ghana, I was both victim to and observer of the inexplicable effects of a strange and frightening force. I have my own eyes and ears to believe, my own intelligence to depend on, my injuries to confront me every waking hour of my life. There is not a shred of doubt in my mind today that the African, in his own mysterious ways, has harnessed one of the strangest powers of all – the thing they call Ju-ju. (Neal Reference Neal1966:191)

It must be stressed here that the question of whether or not juju works or the perceived protective and destructive power of juju has any credibility is beyond the scope of this study. The only reason for sharing parts of James Neal’s experiences in Ghana is to portray a more vivid picture of juju and some of the ways of performing juju rituals.

Historical Developments of Ritual Murder in Africa

It is unknown exactly when and how human beings came to be used for juju or ritual medicine in Africa. However, Robin Law (Reference Law1985) maintains that the belief that human beings can be sacrificed for a desired end has existed on the continent since pre-colonial times. Indeed, human sacrifice has been practised throughout history in various cultures, and those in Africa are no exception (Davidson Reference Davidson1980; Isichei Reference Isichei1977; Law Reference Law1985). It has been widely reported by various anthropologists, historians, and Western observers and researchers that among the Asante of Ghana, the Yorubas, Ibos, Calabars and other groups in Nigeria, and the people of Dahomey (now Benin), when a king or paramount chief died, certain people were killed to be buried with him (Dalzel Reference Dalzel1967; Dupuis Reference Dupuis1966; Fynn Reference Fynn1971; Johnson Reference Johnson2010; Law Reference Law1985; Rattray Reference Rattray1927). One social anthropologist, Peter Kwasi Sarpong, explains that the practice of killing people and burying them together with deceased kings or chiefs was motivated by the belief that in the place of the dead, departed souls are “supposed to lead exactly the same life that … [they] led while on earth. A chief here is a chief there, a farmer here is a farmer there.” (Sarpong Reference Sarpong1974:38) Those slain were thus supposed to serve the deceased kings or chiefs in the world of ancestors.

Human sacrifices were also carried out among some African communities or groups in times of war. One popular instance where human sacrifice was performed in an African setting to ensure victory in war occurred during the Asante–Denkyira war, commonly known as the battle of Feyiase (the name of the town where the two opposing forces locked horns), between the late 1690s and early 1700s (Anti Reference Anti1971; Kwadwo Reference Kwadwo1994; McCaskie Reference McCaskie2007; Sarpong Reference Sarpong1974). In this particular case, Okomfo Anokye, unarguably the most celebrated traditional priest in the history of Ghana, who was a bosom friend of the then Asante monarch (King Osei Tutu I), divined that the Asante would be victorious only if three chiefs volunteered to be sacrificed – one was to be buried alive, the second was to be slaughtered for vultures to feed on his flesh, and the third volunteer would lead the Asante soldiers fully armed but would not fire a weapon or defend himself even if he was attacked by the enemy. Three chiefs volunteered to be sacrificed, and the Asante won the battle (Anti Reference Anti1971; Kallinen Reference Kallinen2016; Kwadwo Reference Kwadwo1994; Mbogoni Reference Mbogoni2013; McCaskie Reference McCaskie2007). The fact that the Asante people were victorious as predicted by the fetish priest, perhaps, reinforced the belief in the efficacy of human sacrifice (or rituals with human ingredients) and the belief that certain individuals in society have extraordinary powers to manipulate events.

Therefore, it is apparent that human sacrifices in pre-colonial Africa were largely carried out during wartimes to guarantee victory; in times of communal crises such as droughts, famine, epidemics, and other disasters to obviate such calamities; and to invoke special blessings for the community. Human beings were also sacrificed to fulfill and preserve age-old customs and traditions of a group of people (Gocking Reference Gocking2000; Igbinovia Reference Igbinovia1988; Law Reference Law1985; Mbiti Reference Mbiti1969). These customs included thanking the gods or seeking favours from them during festive occasions or when the need arose and maintaining the quality of life of an ancestor or a deceased king in the ancestral world (Gocking Reference Gocking2000; Law Reference Law1985; Mbiti Reference Mbiti1969; Wilks Reference Wilks1988, Reference Wilks1993). Law (Reference Law1985:58) thus defines human sacrifice “as the killing of people to secure the favour of supernatural beings” and guarantee the achievement of communal goals.

By the early 1940s, human sacrifice was no more a noticeable feature of traditional African communities; however, a similar practice known as ritual murder had become widespread in various parts of the continent (Gocking Reference Gocking2000; Murray and Sanders Reference Murray and Sanders2000). It is worth noting that even though both killings (human sacrifice and ritual murder) may be carried out in a ritualistic fashion, in that victims are usually “killed in carefully prescribed ways for religious or occult purposes” (Gocking Reference Gocking2000:198), many experts and academics distinguish between human sacrifice and ritual or medicine murder (Evans Reference Evans1993; Gocking Reference Gocking2000; Murray and Sanders Reference Murray and Sanders2000; Wilks Reference Wilks1993). Patrick Edobor Igbinovia describes ritual murders as “a particularly violent and extreme type of criminal homicides in which the slayers excise the vital organs of the victims for use in ‘sacred’ rites” (Igbinovia Reference Igbinovia1988:37). Closely related to this definition is that of Roger Gocking, who describes ritual murder as a killing “carried out to use the victim’s blood and body parts to make a powerful medicine for an immediate objective” (Gocking Reference Gocking2000:198). Jean La Fontaine explains that “[w]hereas human sacrifice was performed openly and as part of rituals that were believed to benefit the community, … [ritual] murders are furtive and hidden, fuelled by individual ambitions and the lust for wealth and power” (La Fontaine Reference La Fontaine2011:9).

The belief among adherents of juju rituals is that the more valuable the object used in the manufacture of the medicine/charm or the performance of the ritual, the more potent the power of the medicine or the rite (Neal Reference Neal1966). Thus, it has been suggested that the idea of using human blood or body parts for ritual/magical medicine stems from the view that humankind is the most superior entity on earth; therefore, medicines containing human flesh and/or blood should necessarily be more potent than those made with non-human ingredients (Labuschagne Reference Labuschagne2004; La Fontaine Reference La Fontaine2011; Mabiriizi Reference Mabiriizi1986). Hence, once approached by a client, the juju specialist would decide whether the nature of the request/supplication from the client would require a medicine made with leaves/plants, animals, human blood and body parts, or other objects/ingredients (Labuschagne Reference Labuschagne2004).

By 1949, murders carried out in a ritualistic fashion had become alarmingly prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa, especially in British colonies – the Gold Coast (now Ghana), Nigeria, South Africa, Swaziland, Basutoland (now Lesotho) and other countries (Evans Reference Evans1993; Murray and Sanders Reference Murray and Sanders2000; Pratten Reference Pratten1998, Reference Pratten2007; Rathbone Reference Rathbone1993). Consequently, the British Government appointed a Cambridge anthropologist, G. I. Jones, to investigate the underlying causes of the obvious increase in ritual murders, particularly in Basutoland and to make relevant recommendations. Jones’s (Reference Jones1951) report established, inter alia, that ritual or medicine murders were inspired by the belief in juju. The upsurge in the number of ritual homicide cases was motivated largely by power struggles among chiefs, heads or leaders of various clans, and members of various royal families. It further explained that the indirect rule policy implemented in British colonies brought about fierce political competition and disputes, which ultimately led to a rise in ritual murders (Jones Reference Jones1951; see also Ko and Kulkarni Reference Ko and Kulkarni2019; Mabiriizi Reference Mabiriizi1986).

The indirect rule system (i.e. ruling through pre-existing indigenous power structures) meant that only kings and chiefs and people from royal families could play significant roles in political activities. This resulted in a situation where various groups and prominent figures who wanted to actively participate in the political administration of their area (what the government described as the “native state”) genuinely or falsely claimed that they were either members of the reigning family or the only true royals of that native state. This triggered numerous chieftaincy-related disputes and litigations, which ultimately inspired opposing factions to perpetrate ritual murders in the belief that the blood and body parts of the victims could be used to make a potent medicine that could help tip the scales in their favour or make them succeed in their legal battles and struggles for power (Gocking Reference Gocking1994, Reference Gocking2000; Jones Reference Jones1951; Ko and Kulkarni Reference Ko and Kulkarni2019; Mabiriizi Reference Mabiriizi1986). According to Bonny Ibhawoh (Reference Ibhawoh2013), out of 38 randomly selected African criminal appeals that came before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) between 1930 and 1945, 19 involved juju-related murders, motivated largely by the ambition for royal and political power.

Studies and reports show that ritual paedicides have become endemic in most contemporary African societies. However, due to the enormous size of the African continent, it has been considered reasonable to focus attention only on Ghana to gain insights into the magnitude and primary features and the socio-cultural and economic contexts of juju-concomitant paedicides on the continent.

JUJU AND RITUAL PAEDICIDE IN GHANA

The Extent of Juju Beliefs in Ghana

The belief in juju is widespread in Ghana and several other African countries (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005, Reference Adinkrah2017; Neal Reference Neal1966; Smith Reference Smith1929). In a study conducted by the Pew Research Center, over a quarter of Ghanaians, both Christians and Muslims, mentioned that they believe in the protective power of juju (Pew Research Center 2010). However, this is an underestimation, as several accounts, reports and studies suggest a far higher rate for belief in juju and its protective and destructive power in the country (Appau and Bonsu Reference Appau, Bonsu, Roy Chaudhuri and Belk2020; Max-Wirth Reference Max-Wirth2016; Neal Reference Neal1966). Writing about the pervasiveness of the juju belief in Ghana in the late 1920s, Major E. H. Smith, the assistant commissioner of the Ghana police, makes the following observation: the “employment of fetish and juju (charms) plays a prominent part in the life of the inhabitants of the Gold Coast, despite modern influences. When something of vital importance occurs, resort to juju is frequently made even by those West Africans who in everything else are orthodox Christians.” (Smith Reference Smith1929:316). Sharing some of his experiences in Ghana in the 1950s, one British expatriate also makes the following observation: “I can tell you for a fact that Ju-ju is practised extensively all around the native villages – in fact, all over the country. And whether you care to believe it or not, it is powerful.” (cited in Neal Reference Neal1966:16). In a recent survey involving 200 educated and non-educated respondents, Emmanuel Owusu (Reference Owusu2021) found that approximately 82% of Ghanaians believe in juju’s protective and destructive power. Interestingly, 11 out of the 20 people (all educated) who participated in the semi-structured interviews for the present study seemed to believe that juju works – it is powerful.

In Ghana, a juju practitioner is known locally by names such as mallam (a term for a “spiritually powerful” Islamic cleric), odunsenii (an Akan term for a traditional healer) or juju-man or juju-woman. Such figures are consulted regularly in the country (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005; Meyer Reference Meyer1998, Reference Meyer2001; Smith Reference Smith1929). In a recent study that sought to explore the place or role of spiritual consultants (i.e. church pastors and traditional spiritualists) in the marketing of religion in contemporary Ghana, Samuelson Appau and Samuel Bonsu (Reference Appau, Bonsu, Roy Chaudhuri and Belk2020) found that some Ghanaians pay a fee to consult mallams or juju practitioners, many of whom use roadside (outdoor) advertising to attract clients. It must be stressed that even though juju practitioners generally “have the power” to protect (enhance the wellbeing of people) and to destroy (harm or kill clients’ adversaries), many use their powers for only a good cause – the protection of people in society and the enhancement of human wellbeing (see Neal Reference Neal1966), and also employ a more acceptable technique such as the use of non-human objects for the relevant rituals or medicines.

In Ghana, juju medicines are sought by all manner of people for all kinds of reasons. Poor people seek juju for prosperity or wealth; the rich contact juju specialists for protection and fortification; sports folks rely on juju for success or victory; pastors of Pentecostal churches use juju in order to perform miracles and draw people to their churches; university students use juju to manipulate lecturers and examiners and to get good grades; business persons consult juju specialists for rituals that guarantee or enhance the progress of their businesses; royals (e.g. chiefs and queens) resort to juju for protection, long life and the destruction of rivals; politicians rely on the powers of juju specialists to win elections, ensure their hold on political power and for protection against those who may seek to harm them; and unmarried and childless women place their confidence and trust in juju for partners and children (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005; Lipinski Reference Lipinski2013; Max-Wirth Reference Max-Wirth2016; Meyer Reference Meyer1998, Reference Meyer2001).

In April 2020, a 64-year-old biochemist (a pensioner) allowed himself to be deceived by a juju-man and his assistant into believing that if he gave them GH¢10,650 (£1,420), they could conjure GH¢400,000 (£53,333) from it for him. Sadly, the spiritualists murdered him after being given the money (Mensah Reference Mensah2020; Ghana News Agency 2020b). The desire to become super-rich overnight got the better of the biochemist’s critical judgement. The fact that a highly educated pensioner (biochemist) fell for the lies and tricks of juju-men shows the extent of the juju belief in contemporary Ghanaian society.

The Magnitude of Ritual Paedicide in Ghana

It has been asserted that many of the child murders committed in Ghana are prompted by the belief in juju, as juju specialists, at times, seek human blood and/or body parts to use as purported remedies to address their clients’ problems or facilitate the achievement of their goals and ambitions (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005, Reference Adinkrah2017; Owusu Reference Owusu2019). The foremost characteristics of a ritual murder are missing body parts of the victim and visible sign(s) of the draining of the victim’s blood (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005; Browne Reference Browne2000; Gocking Reference Gocking2000; La Fontaine Reference La Fontaine2011; Murray and Sanders Reference Murray and Sanders2000). Presently, reliable data on ritual paedicide rates in Ghana are non-existent; and only one empirical study on ritual murder (not specifically on ritual paedicide) in the country seems to exist (see Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005). However, various court records, reports and a few relevant extant academic literature suggest that juju-driven child homicide is widespread in the country (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005, Reference Adinkrah2017; Gocking Reference Gocking2000).

One of Ghana’s earliest recorded juju-fuelled paedicide cases is Rex v. Agidegita Afaku. This case concerned a fetish priest who murdered a little girl to use her bones for juju rituals in the Volta Region. On 13 July 1943, he was found guilty of murder and condemned to death by hanging. He was executed on 20 September 1943 following the dismissal of his appeal by the West African Court of Appeal (WACA) on 28 August 1943. Approximately two years after this episode, the courts were invited to deal with another juju-involved paedicide case – Rex v. Kweku Awusie and Four Others. In this case (popularly known as the Bridge House murder case), in March 1945, the five defendants brutally murdered a 10-year-old girl and dumped her remains on a beach near Elmina in the Central Region. Distressingly, the victim’s “upper and lower lips, both cheeks, both eyes, her private parts and anus, and several elliptical pieces of skin from different parts of her body had been removed” when her body was discovered a couple of days after her disappearance (Gocking Reference Gocking2000:197).

It was established at trial that there was a chieftaincy dispute between two groups – a bitter factional dispute over succession to the throne of the Edina State (or Elmina State). The young girl had thus been murdered so that her body parts could be used for rituals meant to facilitate or guarantee victory for the suspects’ faction in a pending case in court. J. N. Franklin, superintendent of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), who investigated the case, explains that the ritual was performed in the belief that it had the power to cause the persons using it to succeed in any court case that they may be involved with (Franklin Reference Franklin1945). All the accused were found guilty of first-degree murder by an Accra Criminal Assizes court and sentenced to death. They were hanged in early February 1946 after their appeals had been turned down by the WACA and the Privy Council on 28 June 1945 and 14 January 1946, respectively (Gocking Reference Gocking2000). Due to the swift and professional manner in which the country’s criminal justice system dealt with ritual murder cases in the 1940s, the rate of ritual murder cases reduced significantly. However, during the mid-1980s, according to Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2005) and Birgit Meyer (Reference Meyer2001), the country began to experience another ritual murder epidemic.

In a study that sought to explore the features, motivations and socio-cultural context of ritual homicide in Ghana, Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2005) identified 24 cases of ritual murder publicized in just one local Ghanaian newspaper between 1990 and 2000. Of the victims, six were aged between 0 and 10 years, and four were between 11 and 20 years. The study found that most of the perpetrators were motivated by pecuniary gain. Apart from the draining of victims’ blood, the organs most often extracted from the victims were the private parts, heart, head, liver, eyes and tongue (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005). In another study that examined commercial transactions involving the sale of children in contemporary Ghana, Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2017) identified 20 cases of commercial transactions in children in the country. Troublingly, eight of the 20 cases analysed involved perpetrators who attempted to sell the victims to juju-men, knowing very well that the children would be killed and their body parts and blood used in the preparation of juju medicine. Fortunately, the culprits were apprehended before carrying out their evil agenda.

Since there is no reliable estimation of the rate of ritual murders, particularly ritual paedicides, in contemporary Ghana, it was considered extremely useful to conduct a dynamic media content analysis to establish the magnitude and identify primary features of the ritual paedicide phenomenon.

METHODOLOGY

A thorough analysis was conducted of ritual murder cases/reports published on the websites of three renowned local Ghanaian media outlets between September 2013 and August 2020. This approach is relevant and suitable for the present study as there are, currently, no reliable data and empirical study on ritual paedicide in Ghana. Media reports are thus the primary means through which such episodes come to the general public’s attention. Therefore, it is almost impossible to explore the magnitude, motivations and principal features of ritual paedicide in the country without recourse to relevant media publications. Indeed, using newspapers or the media to study homicide is not an untested approach. Academics and researchers such as Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2004, Reference Adinkrah2005, Reference Adinkrah2020), Peter Chimbos (Reference Chimbos1998) and Neil Websdale and Alex Alvarez (Reference Websdale, Alvarez, Bailey and Hale1997) have all effectively utilized this method to understand homicides in different geographical settings. Newspaper or media use in homicide studies is very useful, particularly in developing countries where crime statistics are usually non-existent or poorly documented (Stöckl et al. Reference Stöckl, Dekel, Morris-Gehring, Watts and Abrahams2017). Besides, ritual murders, as Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2005) observes, are not officially recorded as a separate category of homicide in Ghana. In other words, murders are not categorized into offences such as femicides, infanticides, siblicides, uxoricides, and others. This makes it difficult to determine what percentage of murders committed each year is ritual paedicide and make relevant and informed comparisons and analyses. Therefore, it was considered suitable to critically analyse pertinent media reports to understand the scale and socio-cultural, religious and economic contexts of the child murders that result from juju beliefs in Ghana.

The selected local media outlets were: the Daily Graphic and Ghanaian Times (state-owned newspapers) and the Daily Guide (a privately owned newspaper). In terms of circulation and readership, these are the three largest newspapers in Ghana; hence, they were selected as a data source. The Daily Graphic, founded in 1950, is a renowned national daily newspaper that has the largest circulation (100,000 daily) and readership (approximately 1.5 million readers per day) in Ghana (Elliot 2018; Hasty Reference Hasty2005). It has highly trained investigative reporters posted to every corner of the country and usually at crime scenes (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2004, Reference Adinkrah2011; Yankah Reference Yankah1994). The quality, accuracy and depth of reporting and coverage make it the most reputable newspaper in Ghana. The Daily Guide (or Daily Guide Network), started in 1984, is one of the few well-known, well-managed and widely read daily newspapers in Ghana (Anercho Abbey Reference Anercho Abbey2019). It is the second most popular newspaper and the largest privately owned daily in the country, enjoying a daily readership of close to 800,000, constituting approximately 18.9% of the total audience share (Anercho Abbey Reference Anercho Abbey2019; Elliott Reference Elliott2018). It has well-trained reporters in all parts of the country and provides detailed and accurate accounts of crimes, strange incidents and dramatic events. The Ghanaian Times is also a reputable state-owned daily newspaper established in 1957. It is the third-largest newspaper in Ghana, with approximately 530,000 readers per day (Elliot Reference Elliott2018). Like the Daily Graphic, the Ghanaian Times has “journalists, majority of whom have been trained in recognized institutes of Journalism … [T]he traits of the journalists include curiosity, commitment, integrity, accuracy, dependability and discipline.” (Yankah Reference Yankah1994:51)

To obtain the relevant reports on juju-related murders, a search was conducted on the websites of the three selected media outlets, using the following key phrases: “juju ritual”, “juju medicine”, “occult ritual”, “ritual murder”, “ritual killing”, “ritual homicide”, “juju ritual and murder”, “occultism and murder”, “human body parts” and “ritual murder in Ghana”. Particular attention was paid to key information such as the number of ritual murder cases that occurred and were reported in the selected media during the study period (September 2013–August 2020); how the murders were carried out; age, gender, and socio-economic status of perpetrators and victims; victim–offender relationship; arrest and conviction rates; motivations for the murders; and how the criminal justice system handled the cases. Every relevant case/report was counted only once. Thus, where a case was reported by more than one of the selected media, the report that appeared to be more detailed and coherent was adopted, and the corresponding media outlet got the credit for the publication. Where a selected report on a case was still not detailed or intelligible enough, reports on the same episode published or broadcast by other reputable media platforms other than the three selected ones were reviewed for a clearer and more detailed description of the case.

For the purpose of this study, a murder case was classified as juju-related killing or ritual murder if body parts were extracted, blood was drained, and there was evidence that a ritual had been performed on the body or at the crime scene; and, in addition to one or more of these three elements, law enforcement authorities or many of the relevant community members believed that it was ritually motivated. Murder was also classified as ritual homicide if perpetrators or suspects confessed that they committed it for ritual purposes, irrespective of the condition of the victim’s remains at the time that they were discovered. Ritual murder was also assumed in instances where persons found in possession of fresh human body parts could not explain away how they obtained them, and there was no evidence that they had been taken from a graveyard. There is no denying that not every ritually motivated murder requires or involves the extraction of the victim’s blood and body parts (La Fontaine Reference La Fontaine2011), and not every murder with some body parts of the victim removed may necessarily be a ritually motivated killing. However, it is felt that adopting the criteria generally used in Ghana and other African countries for determining or identifying a juju-fuelled murder is appropriate and reasonable despite its obvious limitations.

To gain additional insights into the results obtained from the content analysis and into other intricacies of ritual paedicide, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 relevant individuals (10 males and 10 females). They were selected using the purposeful sampling technique, as the study required participants with a reasonable level of expertise in and understanding of the phenomenon investigated. Thus, interviewees were either selected by the researcher or recommended by others based on or due to their acclaimed expertise/knowledge in child welfare, paedicide, ritual murder, criminology, sociology and/or African religions; their considerable interest or involvement in campaigns for the protection of children’s rights; and/or their privileged position as custodians of customs and tradition. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, interviews were conducted via phone or web conferencing. The interaction focused on key issues such as the possible factors responsible for the persistence of, and the perceived increase in, ritual paedicides in Ghana; why certain groups of people are usually targeted and why other groups tend to be the dominant culprits; the extent to which low socio-economic status impacts ritual paedicide; the efficiency and effectiveness of the criminal justice system in responding to ritual paedicide cases; and how the problem could be combatted, among several other issues. It is worth stressing that the term “child” is used in this study to refer to a person below the age of 18 years as defined by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989 and the Ghana Children’s Act 1998.

Ethical Considerations

Two ethical issues did arise in the present research – confidentiality and the issue of transcript validation and ratification by interviewees. Of the 20 participants, 16 consented to be quoted and to have their real names and other relevant information such as their profession and area of expertise included in the written report/manuscript, and the remaining four only gave the researcher permission to quote them without using their real names or identifying them. To respect and protect the confidentiality of the four participants who did not want their identity to be revealed, the phrase “Name withheld” was used when incorporating quotations from them into the report/manuscript. Before quotations were included in the report/manuscript, the relevant transcripts were sent to the respective participants for further examination, amendment (addition, deletion, correction of language) if necessary, validation and/or ratification of content. The rationale was not only to avoid misquotation and misinterpretation but also to ensure and preserve the authenticity or accuracy of that which the participants said during the interviews, and ultimately enhance the quality of the study and the credibility and trustworthiness of the findings.

RESULTS

Statistics on Ritual Murder in Ghana

A thorough search of the three selected media websites for reports on juju-related homicides spanning 2013–2020 yielded disturbing results. In all, 96 different reports on ritual homicide were identified, 53 of which involved child victims. On the Daily Graphic website, 36 different reports were retrieved; as many as 17 were about child victims only, and four concerned children and adults. A perusal of the Ghanaian Times website produced 28 different cases; 12 of them were about children only, and three concerned both children and adults. On the Daily Guide website, 32 reports were found; 17 were exclusively about child victims. This information is summarized in Table 1. It must be pointed out that a single report or story may concern two or more victims. The 96 reports extracted from the websites of the three media outlets thus involved approximately 116 victims, about 62 of whom were children. Killing older people (folks aged 60 years or more) was very rare for ritual purposes.

Table 1. Number of Relevant Reports Found in Each of the Selected Media

Statistical Information on Ritual Paedicide in Ghana

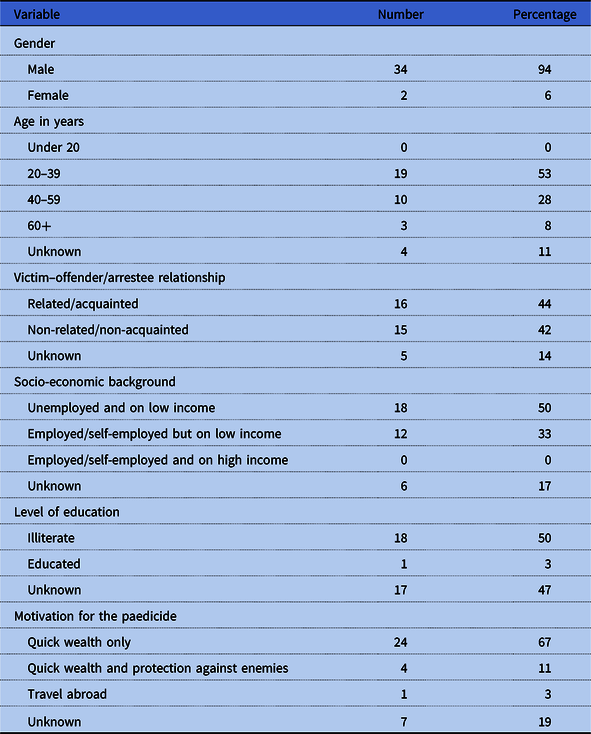

The 62 child victims were aged between 4 and 17 years. A total of 36 arrests (including two convictions) were confirmed in 19 of the 53 reports concerning child victims. Perpetrators or suspects were still at large in the remaining 34 reports. Of the arrests and charges, 29 were based on self-confession or the offenders being caught red-handed (i.e. apprehended while selling human body parts or looking for a potential buyer). Tables 2 and 3 present information on the victims and perpetrators and key characteristics of ritual paedicide in Ghana.

Table 2. Information on 62 Child Victims of Ritual Paedicide in Ghana

Table 3. Information on 36 Perpetrators/Arrestees of Ritual Paedicide in Ghana

Gender Differences

There was no significant difference in the number of boys and girls murdered. Many of the murders involved multiple culprits. Almost all the perpetrators and prime suspects (including those arrested and their accomplices still at large) were males. As Table 3 indicates, most of them were aged between 20 and 39 years and were mostly unemployed or financially handicapped. Only two of the prime suspects were females. Worryingly, most of the perpetrators were neither apprehended nor identified. The data indicate that perpetrators of ritual paedicide are strangers nearly as often as being family members and acquaintances. Fathers, stepfathers and uncles were the dominant culprits in cases where victims and perpetrators were related. Most of the victims (over 79%) were from rural and semi-rural communities. Most of them were of low socio-economic backgrounds. Not a single victim seemed to have hailed from an affluent family.

Parental Supervision

Lack of proper parental supervision was the major cause of the abduction of the children, who were eventually murdered for ritual purposes. Over 70% of the victims were kidnapped while playing outside their homes unsupervised, going to school or fetching water from a stream unaccompanied, or running errands for their parents or other family members. The data also suggest that children between the ages of six and 10 years are more at risk of being victims of ritual paedicide than those in other age groups. In one of the cases, the victim’s body was so badly decomposed that the exact age and/or gender could not be determined by the reporters or the police officers and investigators at the scene. Victims’ remains were mostly found in remote locations. The head, limbs, genitalia/private parts and tongue were the body parts mostly extracted from victims. For unknown reasons, ritual paedicide cases were more prevalent in the western part of Ghana than in other areas of the country.

Main Motivation

The dominant motivation mentioned by those who confessed to committing the ritual paedicides that they had been accused of or charged with was financial gain. Some perpetrators had been promised money in exchange for the supply of particular human parts. Other killers first murdered the victims and then searched for prospective buyers (e.g. juju practitioners), erroneously believing that every juju practitioner would be interested in buying human body parts. The third group consisted of individuals who had consulted juju practitioners for some help, and they had been instructed to provide specific body parts to be used for rituals or medicines that would produce the desired effect. However, in one of the reports, two young teenagers who consulted a juju practitioner for quick wealth ended up being themselves the murder victims. There was no clear indication that any of the perpetrators or arrestees were mentally disordered when the respective offence was committed.

Law Enforcement Role

The data suggest that law enforcement agencies arrived at many of the crime scenes several hours (in some cases, over eight hours) after discovery of the bodies had been reported to them. In some cases, officers were reluctant to search for missing children when their disappearances were reported at the police station. At times, the discovery of victims’ bodies led to protests by residents who blamed the murders on police laxity and failure to investigate previous cases and apprehend culprits. In some reports, enraged residents assaulted suspects or set their property ablaze out of frustration and lack of trust in law enforcement agencies. Suspects and perpetrators whom community members caught were usually beaten up mercilessly. At least one suspect was lynched.

LIST AND SUMMARY DESCRIPTION OF 15 CASES

Table 4 shows the captions and summaries of 15 relevant ritual paedicide cases/reports identified on the three perused websites. The carefully selected cases/reports provide a reasonable and clearer idea of key features of ritual paedicide in Ghana. The summaries of the selected reports have been presented chronologically by the first publication date (from September 2013 to August 2020).

Table 4. Captions of Ritual Paedicide-Related Stories/Reports Publicized Between 2013 and 2020

In report/case number 1, a 22-year-old man beheaded his 15-year-old nephew intending to use the head and blood for a ritual that would enable him to raise GH¢2,000 (£270) to process his documents to travel abroad. The suspect reportedly confessed to police that he invited the victim into his room, held him down, and decapitated him using a sharp machete with the help of his (the suspect’s) brother. The boy’s headless body was later discovered and retrieved from the suspect’s bedroom. According to the police, the suspect, who initially denied conspiring to murder and murdering his nephew, later burst into tears and confessed, stating that the spirit of his nephew was haunting him. His accomplice was on the run at the time of his arrest (Aklorbortu and Obuor Reference Aklorbortu and Samuel Obuor2013).

Report number 2 was about a four-year-old girl beheaded by her 45-year-old stepfather for ritual purposes. This incident resulted in the suspect being lynched by an angry mob. It is reported that after killing and decapitating the girl, the suspect wrapped the head in a polythene (plastic) bag and headed for the lorry station, apparently to send it to a juju-man for a money-making ritual. A trail of blood led an inquisitive passer-by to a room where the girl’s headless body was discovered. The individual immediately raised the alarm, resulting in neighbours chasing the suspect to the lorry station and mercilessly beating him up before handing him over to the police. He was rushed to a local hospital by the police but died shortly on arrival (Aklorbortu and Arku Reference Aklorbortu and Arku2013).

In report number 3, irate youth in one town clashed with the police over the suspected ritual murders of an eight-year-old girl and two adult males in the area. The little girl is believed to have been murdered on her way to fetch water from a stream in the town. An adult male lunatic was also found dead with his two hands and other body parts chopped off. The third victim was a watchman slashed with a machete in the head. Irate youth in the community attempted to force their way into the chief’s palace to lynch two suspects who were being given protection by the chief. The angry youth pelted the police officers who had gone there to restore peace and order with stones and other objects, injuring three (Mohammed Reference Mohammed2015).

In report number 4, an older woman and two men were arrested by the police in connection with the suspected ritual murder of a 10-year-old boy whose body had been dumped in a bush. The facts of the case are that on 13 October 2016, a 65-year-old woman reported to police that her grandson with whom she was living in a rented room was missing. Suspiciously, the report was lodged three days after the child’s disappearance. A few days later, the lifeless body of the missing boy was found without the penis, left arm and right kneecap. The inconsistency in the woman’s account of what happened the day the boy disappeared compelled investigators to subject her to rigorous interrogation, leading to the arrest of two male suspects. Police believed that the boy was sold by his grandmother to some unknown persons who killed him for ritual purposes (Abbey Reference Abbey2016).

Report number 5 concerned a 17-year-old girl found dead in the Greater Accra Region under strange circumstances. The girl had disappeared from the community a few days prior to the discovery of her body. Her private parts had been extracted when the body was discovered. The missing body parts and other features consistent with ritual homicide heightened residents’ belief that the girl was murdered for ritual purposes. No one had been arrested, and no suspects had been identified/named when the report was filed (Sarpong Reference Sarpong2017).

Report number 6 highlighted a series of suspected ritual murders that hit one municipality and sparked a massive demonstration by residents of the affected communities. According to the report, between September 2016 and March 2017, about six people were murdered ritualistically in about seven communities. The victims included children between the ages of seven and 13 years. It was rumoured that some of the persons behind the killings were fishers who used the bodies for rituals that would guarantee bumper harvests in their fishing activities. The incessant killings and the failure of the police to conduct serious investigations resulted in fear, insecurity and anger among residents, who then staged a massive demonstration to draw the attention of the security authorities and the government to their plight (Anane Reference Anane2017).

In report number 7, a 36-year-old man was arrested by police, in a farming community, for murdering his six-year-old son for rituals. The facts of the case are that the victim’s mother reported to the elders of the community that her little son had gone missing. A search by members of the community yielded no positive result. A couple of days later, the missing boy’s remains were found with the head and left leg severed. Events that occurred prior to his disappearance induced some local folks to view his father as a prime suspect. Police subsequently invited the father for questioning. He confessed that he murdered the boy to send the head and the legs to a spiritualist for money rituals (Ghana News Agency 2017; Opoku Reference Opoku2017).

In report number 8, a 23-year-old man was arrested for having a fresh human head, which turned out to be that of a 12-year-old boy. When the victim who left home for school in the morning failed to return, his worried father requested a radio station to make a missing child announcement. He later received a call to report to the local police station only to be shown the decapitated body of his son. The perpetrator reportedly lured the young boy with money to a nearby bush on his way back from school and beheaded him. He attempted to sell the boy’s head to a juju-man in another town, but the spiritualist rejected the deal and raised the alarm, leading to the suspect’s arrest. Upon interrogation, the assailant confessed that he murdered the boy, with the help of two other accomplices (still at large), for money rituals (Opoku Reference Opoku2018).

Report number 9 concerned a five-year-old boy decapitated by two male suspects, aged 21 and 25 years. The victim was on his way to watch a video game with his twin sister when he was lured with yoghurt to a secluded spot in the city of Kumasi, abducted and later decapitated by the suspects. His headless body was then dumped in an uncompleted building. However, the perpetrators were arrested when they approached a known mallam (a spiritualist) they believed would be interested in buying the severed head to perform juju rituals for his clients. The mallam, who feigned interest in the deal and agreed to pay GH₵2,500 (£350) for the new human head, alerted law enforcement officers who arrested the suspects (Adu Reference Adu2018; Tawiah Reference Tawiah2018).

In report number 10, four persons were arrested by the police in connection with the murder of a 14-year-old girl. According to the facts of the case, the young girl left home on the morning of Saturday, 12 January 2019. When she failed to return home, her father got worried and lodged a missing child report with the police. Shortly after, a search party discovered the young girl’s lifeless body in a nearby cemetery. A careful examination of the body showed evidence of draining of blood. The father advised the police to interrogate a 35-year-old man he suspected of abducting and killing his daughter, but, suspiciously, the suspect was nowhere to be found. The suspect was eventually arrested and interrogated, and he confessed that he and three other persons killed the young girl for money rituals. His accomplices were also arrested (Opoku Reference Opoku2019a).

Report number 11 concerned a 16-year-old boy whose body was found in a forest reserve. The facts of the case are that the victim, who was living with his aunt, left home but never returned. A couple of days later, the child was reported as missing at the police station. Shortly after, distress calls were made by some residents to local radio stations, reporting the discovery of a partially decomposed body in the forest reserve. The information was relayed to the police, who subsequently went to the scene to investigate. According to some residents who saw the body before it was conveyed to the morgue for autopsy, some wounds suggested that his blood had been drained, and parts of his body had also been mutilated (Opoku Reference Opoku2019b).

Report number 12 was about a child whose body was discovered floating on a river. It was claimed that a bottle of schnapps and some potions contained in an earthenware bowl were found on the bank of the river in which the body was discovered, heightening suspicions that the murder was ritually motivated. The body was so decomposed that investigators at the scene could not determine the gender or exact age of the deceased, but they believed the victim could be seven or eight years. Police preliminary investigations revealed no reports of a missing child in the area, and residents were not aware of any missing child in the neighbourhood recently, indicating that the victim might have been abducted elsewhere (Tenyah-Ayettey Reference Tenyah-Ayettey2019).

Report number 13 concerned a 15-year-old girl murdered by unknown assailants during a short school vacation. The young student in boarding school had returned home for a short vacation when she disappeared. A week later, her body was found in a bush with her limbs, private parts and other vital body parts extracted. Her entire hair had also been shaved. It is reported that three females had been murdered similarly prior to this case, and the police had done little to find the perpetrators. The house of a known juju-man in the community suspected of having a hand in the murder of the girl and the previous murders was set ablaze by some irate youth (Hope Reference Hope2019).

In report number 14, a middle-aged man was arrested for decapitating his six-year-old son and attempting to kill two other abducted children for ritual purposes. In September 2019, a tip-off led law enforcement authorities to a cocoa farm where the headless body of a boy was found. The suspect (the victim’s father) was immediately arrested. Upon interrogation, he confessed that he committed the crime with two accomplices, one of whom, he alleged, was the individual who had given the tip-off. He further revealed that he had been contracted to kill three boys for rituals, and he had had two 10-year-olds abducted and kept at the residence of a second accomplice. The plan was thus to murder the two boys after killing his son. He then led police to the second accomplice’s residence, where the two kidnaped boys were rescued (Boye Reference Boye2019; Daily Guide 2019).

Report number 15 concerned three teenage boys (two of them senior high school students) butchered by a juju-man. The facts of the case are that on 18 February 2013, the three boys consulted a fetish priest to prepare a charm called “for girls” (apparently meant for users to get girls’ attention) and double money for them. The fetish priest collected GH₵1,800 (£240), which he promised to double for them. As part of the money-doubling ritual, the spiritualist took them to a remote area and gave them some fresh eggs and concoctions to ingest, causing them to become drowsy almost immediately. He then butchered all three with a machete and disappeared with their money, mobile phones and other items. Fortunately, one of the victims was found alive in the bush by a farmer who took him to a local hospital. Aided by information from the survivor, the police managed to apprehend the perpetrator, who still had some of the stolen items in his possession at the time of his arrest. The fetish priest was in March 2020 sentenced to death by a high court for the two murders (Ghana News Agency 2020a).

DISCUSSION

How Many Paedicides?

The data strongly support the view that juju beliefs and concomitant paedicides are prevalent in Ghana (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005; Meyer Reference Meyer1998, Reference Meyer2001). The results indicate that 17 known ritual murders involving approximately nine child victims occurred in Ghana each year between 2013 and 2020. A report about violent crime statistics in Ghana between 2012 and 2018 shows that an average of 548 intentional murders are chronicled annually in the country (see Tankebe and Boakye Reference Tankebe and Boakye2019). If all the ritual paedicide cases reported in the media were captured in the police official report, then it would be safe to suggest that ritual paedicide (which occurs about nine times a year in Ghana) forms approximately 1.6% of the murders that are perpetrated in the country each year. However, the number of ritual paedicide cases identified in the media may be only the tip of the iceberg. This is because the clandestine nature of ritual murders means that not all episodes come to the attention of the media or the police. Therefore, the media outlets selected and perused may not have known or reported all the ritual paedicides that occurred in the country within the period studied. Some victims may have been secretly buried by their assailants after the desired body parts had been extracted, and the episode may have been classified as a missing child case. Again, because the remains of some murder victims are found at advanced stages of decomposition, some ritualistic murders may be mistakenly classified as accidents, normal murders, or deaths due to an undetermined cause. Besides, some ritual paedicide cases may have been reported under captions that do not contain the search words or terms, making it impossible to identify them during the search process. Other relevant stories may have been reported in print editions only.

The Dominant Motivation

Several factors may account for the prevalence of the juju belief and the rise in ritual homicide cases in the country. However, almost all the interviewees mentioned that widespread unemployment and poverty are at the root of the ritual murder phenomenon. Their assertion is supported by the fact that the dominant motivation for the ritual paedicide cases identified in this study was financial gain. Most of the perpetrators or prime suspects were unemployed or had a low income. In 2016, it was projected that about 300,000 new jobs would need to be created each year to absorb the increasing number of unemployed young people due to the country’s growing youth population. However, a recent study published by the World Bank indicates that the structure of the Ghanaian economy in terms of employment has not seen much change over the last few decades (Dadzie, Fumey, and Namara Reference Dadzie, Fumey and Namara2020).

Currently, there is a perception of the existence of a profitable market in the sale of human body parts (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005, Reference Adinkrah2017). Mass unemployment and associated economic privations have thus “driven some economically disadvantaged people to engage in the nefarious activity of killing and procuring body parts for sale” (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005:49). Thus, with no hope of realizing their financial or economic success through legitimate employment, some Ghanaians, particularly young adults, engage in ritual murders to alleviate the socio-economic hardships. Such people tend to strongly believe that there is an underground market for the demand, supply, and sale of human body parts and that once they have the body parts in their possession, buyers will easily be found (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2017). This explains why some of the perpetrators of the cases analysed committed the murders even before looking for potential buyers. They contact the wrong client in many cases, leading to their arrest.

Many, if not most, of the ritual murderers who get caught obtain the parts before searching for potential buyers (usually juju practitioners). Even though the data suggest that ritual paedicides are almost always committed by poor or uneducated folks, some of the interviewees insist that rich or educated people cannot be entirely excluded from the practice as such people are highly likely to hire others (ideally, poor or unemployed youth) to commit the barbaric crime rather than doing it themselves.

The Consumerist Ethos

Academics and commentators such as Sammy Darko (Reference Darko2015), Meyer (Reference Meyer1998, Reference Meyer2001) and Jane Parish (Reference Parish, Moore and Sanders2001, Reference Parish2011) have also linked the increase in ritual killings in the country to the emergence of a new “consumerist ethos” that has engrossed Ghanaian society. This ethos, as Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2005:50) explains, “is marked by the unbridled quest for material success and the ostentatious display of opulence in the form of handsomely furnished mansions, luxury automobiles, electronics, clothes, jewelry, and other material trappings”. Many Ghanaians, particularly the youth, crave the admiration and respect that come with having such luxurious effects. In an interview, Rev. Fr Dr Lawrence Yaw Gyamfi suggested that many young people who kill for money rituals might have been significantly influenced by the “elegant” (sometimes feigned) lifestyles portrayed by certain individuals, particularly people deemed to be celebrities, on social media. “The desire of much Ghanaian youth is thus to build not just a house, but a mansion.” He was not surprised that the dominant culprits are people aged between 20 and 39 years as this, he opined, is the age group that frequently accesses social media platforms where the so-called big men/women in Ghana usually display their supposed wealth and good living (L. Y. Gyamfi, interview with the author, 29 May 2021). This burning desire “has promoted rampant greed and the acceptance of nefarious means of wealth acquisition” (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2017:2401). Thus, the means through which this conspicuous, elegant lifestyle is realized is deemed less important than the ultimate ends (i.e. possessing money and having the ability to display it). This social context, where affluence or material prosperity is sought by any means possible, “intersects with traditional religious belief systems where it is widely believed that supernatural entities have an interest in, and influence upon, human affairs, including material prosperity” (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005:50).

However, the “consumerist ethos” phenomenon is perhaps not as novel as assumed. Writing about his experiences in Ghana between the 1950s and 1960s, Neal (Reference Neal1966) notes that some people had a tremendous love for money because wealth came with respect, power and authority within Ghanaian society. A person of wealth, in Neal’s own words, “was … considered a ‘Big Man,’ no matter how he obtained his riches” (Neal Reference Neal1966:132). He further states that in his experience, very few Ghanaians ever queried or questioned whether a wealthy person was honest or not. He insists that “[r]egardless of whether he was intelligent or illiterate a ‘Big Man’ was automatically accepted as a leader, and, because of this, it was not so strange that people tried to obtain large sums of money by any means they knew of, including magic” or juju (Neal Reference Neal1966:132).

Cybercriminals: The Sakawa Boys

Currently, in Ghana, there is a group of cybercriminals popularly known as Sakawa Boys, whose cyber fraud is “associated with occult religious rituals believed to compel victims to accede to the perpetrators’ requests” (Oduro-Frimpong Reference Oduro-Frimpong2014:132; see also Quartey Reference Quartey2019; Warner Reference Warner2011). Sakawa Boys (most of whom are less than 35 years old and are usually unemployed) are very popular in Ghana; and are known for their lavish lifestyle, including driving expensive vehicles and living in luxurious houses (Darko Reference Darko2015). Many Sakawa Boys strongly believe that consulting a juju specialist and performing the relevant ritual can speed up and enhance their success in the Internet fraud business (Oduro-Frimpong Reference Oduro-Frimpong2014; Quartey Reference Quartey2019; Warner Reference Warner2011). Many of the interviewees agree with Joseph Oduro-Frimpong (Reference Oduro-Frimpong2014) and Jason Warner (Reference Warner2011) that this group of people widely consults juju practitioners in Ghana for rituals that supposedly protect them and enhance the success of their scamming enterprise. Thus, mallams and other juju practitioners in the country “have taken to performing ‘Sakawa blessing ceremonies’ for youth participating in cybercrime, which are intended to protect cybercriminals from being discovered and ensure their ultimate financial success” (Warner Reference Warner2011:744). Such rituals may involve, among others: “sleeping in coffins for several days at cemeteries; carrying coffins during the night to isolated road intersections”; and producing human body parts to be used for potent medicine (Oduro-Frimpong Reference Oduro-Frimpong2014:134; Warner Reference Warner2011). Thus, Sakawa (scamming) rituals have been blamed for numerous ritual murders over the last decade.

The Obsession with “Juju”

According to some interviewees, Ghanaians’ obsession with juju is exacerbated by the innumerable posters and incessant television and radio advertisements and live programmes by people claiming to have the mystical power to solve virtually every problem plaguing potential clients and to change people’s destiny from bad to good. Indeed, giant posters and billboards promoting the craft and trade of various juju practitioners are found everywhere in Ghana. These signages usually contain the mobile phone numbers and location of the practitioners and a long list of the kinds of “miracles” they can perform. Such activities promote the propagation of the juju belief and its associated violence against vulnerable groups, including children, in the country. Rev. Fr Dr Gyamfi noted:

Due to illiteracy, the average Ghanaian sees everything said on the television and radio as the gospel truth. Some do not do any analysis and critical thinking at all, and they fall for it. Hence, the mallams, traditionalists and prophets capitalize on that to manipulate them. All that television and radio owners/operators care about is to accrue the revenue and not the consequences of the activities of juju specialists on their channels. Unfortunately, no proper state laws regulate what is aired on television or are not enforced. (L. Y. Gyamfi, interview with the author, 29 May 2021)

For instance, in October 2015, information on a juju man’s giant billboard prompted a 19-year-old young man to take his four-year-old nephew to the spiritualist to kill him for money rituals. Fortunately, the priest, whose juju practice did not involve human sacrifice, informed the police who arrested the diabolic fortune-seeker when he showed up at the shrine to present the four-year-old boy for the money ritual on the agreed date (Abbey Reference Abbey2015). Again, as recently as 3 April 2021, two teenage boys, aged 16 and 17 years, unimaginably, lured a 10-year-old boy in their community into an uncompleted building and killed him with a club, a piece of cement block and a shovel. The intention was to use his body parts for a money ritual called “pocked no dry”, a ritual meant to make supplicants rich throughout their entire lives. The teenagers reportedly told investigators that they conceived the idea of killing someone after watching programmes on various Ghana television channels that allowed mallams and other spiritualists to promote their trade and prowess in making people instant millionaires. Convinced by the words of one particular spiritualist who claimed to have the power to make clients wealthy overnight, the teenagers contacted him to make further enquiries over the phone. During their phone communication with the spiritualist, they were instructed to bring human body parts if they really wanted the “pocket no dry” medicine to be effective (Bampoe Reference Bampoe2021; Bonney Reference Bonney2021; Frimpong Reference Frimpong2021).

The rise in ritual paedicide cases in Ghana has also been blamed, to a significant extent, on the massive portrayal of juju and juju rituals as an efficient wealth-guaranteeing religious practice in African movies (particularly those made in Nigeria and Ghana) and the huge exposure of Ghanaian youth to such movies. Juju rituals involving human body parts are often presented in such movies “as a way of obtaining wealth and status when all other routes to fulfilling such desires have become impossible” (Warner Reference Warner2011:745). Simply put, juju rituals in Ghanaian and Nigerian films are typically used to give potency to an endeavour to gain wealth and status overnight.

A Multiple Offenders Crime: Premeditation and Planning

The data confirm the findings of existing studies in Ghana and other African countries that a ritual murder typically involves multiple assailants (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005; Kabba Reference Kabba and Mushanga1992; Scholtz, Phillips, and Knobel Reference Scholtz, Phillips and Knobel1997). Thus, many ritual murders are perpetrated by two or more persons working as a team. There are several possible reasons why a single ritual paedicide usually involves co-conspirators or multiple offenders. Many interviewees suggested that the amount of energy and physicality involved in abducting, restraining and removing victims’ body parts may require a team effort. They also agree with various academics such as Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2005), Kabba (Reference Kabba and Mushanga1992) and Scholtz, Phillips, and Knobel (Reference Scholtz, Phillips and Knobel1997) that conducting such risky operation as a team, perhaps, ensures that there is a division of labour – those serving as lookouts, those abducting and restraining the victim, and those specialized in extracting the desired body parts. Co-offending may also provide some degree of comfort to some assailants as they know that they will not have to endure shame and punishment alone should they be apprehended.

The current data further suggest that, unlike other types of homicide, ritual murder almost always (about 99% of the time) involves premeditation and meticulous planning. The planning encompasses knowing in advance the particular body part to remove and the correct instrument to use, selecting the appropriate victim in terms of gender and age, choosing the crime scene, determining where and how to lure potential victims, and considering beforehand the appropriate steps that must be taken to evade or minimize the risk of detection. As Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2005) notes, the presence of co-conspirators also indicates the extent of premeditation and planning that goes into the crime. Simply put, operating in a group facilitates a coordinated effort that “provides checks and balances as accomplices will recognize and rectify errors and miscalculations in the preparation of the crime” (Adinkrah Reference Adinkrah2005:48).

Why Children? Fragility, Virginity, Purity and Potency

The evidence that over 50% of ritual murder victims in Ghana are children is very troubling. Some interviewees have suggested that children are usually targeted because they are easy prey. Indeed, criminological research shows that crime targets are often vulnerable victims (Daigle Reference Daigle2017; Hough Reference Hough1987). Children are thus perfect targets due to their inability to physically repel physical assaults.

There is also the belief that some medicines are more potent and efficacious if the ingredients used include young victims. Most of the interviewees agree with Adinkrah (Reference Adinkrah2005:48) that “flesh and blood of young sacrificial victims [are believed to] have the greatest potency and purity and that the vitality, strength, and age of youth create a more powerful medicine”. The “purity” and “vitality” attributes may, to some extent, have been drawn from the Ghanaian and, indeed, the African concept of virginity (Owusu Reference Owusu2019).

There is the perception and belief among some Africans that virgins are clean, pure or magical human beings (Leclerc-Madlala Reference Leclerc-Madlala2002; Oluga et al. Reference Oluga, Kiragu, Mohamed and Walli2010) and that the chances of a ritual or medicine producing the desired effect are exceedingly high if a virgin or an item directly linked to a virgin is involved or engaged (Ogbeche Reference Ogbeche2016; Owusu Reference Owusu2019; Rodrigues and Brand Reference Rodrigues and Brand2010). For this reason, people who visit spiritualists to seek wealth, protection, power, longevity and the fulfillment of other aspirations may be instructed to sleep with virgins or provide sexual fluids or body parts of virgins as part of rituals required for the realization of their requests (Alabi Reference Alabi2015; Nwolise Reference Nwolise, Oshita, Alumona and Onuoha2019; Owusu Reference Owusu2019). Explaining why children may be targeted for rituals, one interviewee made the following observation:

Children may be targeted because they are perceived as sexually inactive and therefore more likely to be virgins than adults. Targeting children for rituals requiring body parts of virgins or sex with virgins becomes even more alluring and urgent for perpetrators since it is believed that, in some cases, failure to follow the practitioner’s prescription or direction meticulously may not only make the ritual or medicine ineffective but may also have dreadful repercussions, such as madness or death, on the supplicant. (K. Owusu, interview with the author, 10 January 2021)

The notion that the flesh and blood of young people and virgins significantly enhance the potency of ritual medicines may explain why killing older people for rituals is rare in Ghana.

Ranking of Body Parts