Knowledge of transmission dynamics of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has significant implications for hospital infection prevention and control interventions, timely discharge management, and public health policies. Due to variability in the emerging data, policies on the duration of inpatient and outpatient isolation for people with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have been controversial. Uncertainty continues regarding the significance of prolonged PCR positivity and the clinical importance of various routes of viral shedding. Understanding the duration and sources of viable viral shedding is critical to inform guidance around transmission-based isolation precautions.

We reviewed SARS-CoV-2 viral shedding data to help inform practical decisions related to infection control and public health policies. We reviewed available literature and summarized data on expected duration of viral RNA shedding, longevity of presumed infectivity as detected by viral culture, and factors that may influence shedding duration.

Methods

Search method and data extraction

We queried PubMed, LitCoVID, the World Health Organization COVID-19 literature repository, and Google Scholar for studies and reports available through September 8, 2020. Search terms included of “SARS shedding,” “COVID and viral shedding,” “COVID RNA and culture,” and “COVID culture.” In queries of SARS-CoV-2–specific databases, the words “SARS” and “COVID” were omitted from search terms. Additional studies were identified through review of reference lists of included studies. All authors participated in study identification, screening, and data extraction; all included studies were reviewed by at least 2 authors. Articles reporting duration of SARS-CoV-2 shedding based upon PCR testing or culture directly from human specimens were included. Day 0 was defined as either the day of the first positive test or the day of symptom onset, according to the original study. Studies reporting on exclusively pediatric patients were excluded. For each study, we reviewed the design, objective, population, healthcare system setting, diagnostic testing method, timing of tests, sample source, patient symptoms, and severity of illness. Predictors of prolonged shedding were also considered.

Statistical analysis

We constructed random-effects models using the restricted maximum likelihood estimator for τ 2 to calculate pooled median durations of viral RNA shedding.Reference McGrath, Zhao, Qin, Steele and Benedetti1 All studies providing sample size and sufficient data on measures of central tendency and spread were included in our analysis. We grouped nasopharyngeal (NP), oropharyngeal (OP), saliva, and sputum samples together as “respiratory” samples. Fecal samples included both stool and rectal swabs. We calculated pooled medians among PCR respiratory samples for all available, mild-to-moderate illness, severe-to-critical illness, and for all fecal samples. Insufficient data were available to warrant calculation of pooled medians for culture data. Analysis was performed using R version 4.0.0 software2 using the metamedian package.Reference McGrath, Zhao, Steele and Benedetti3

Results

Included studies

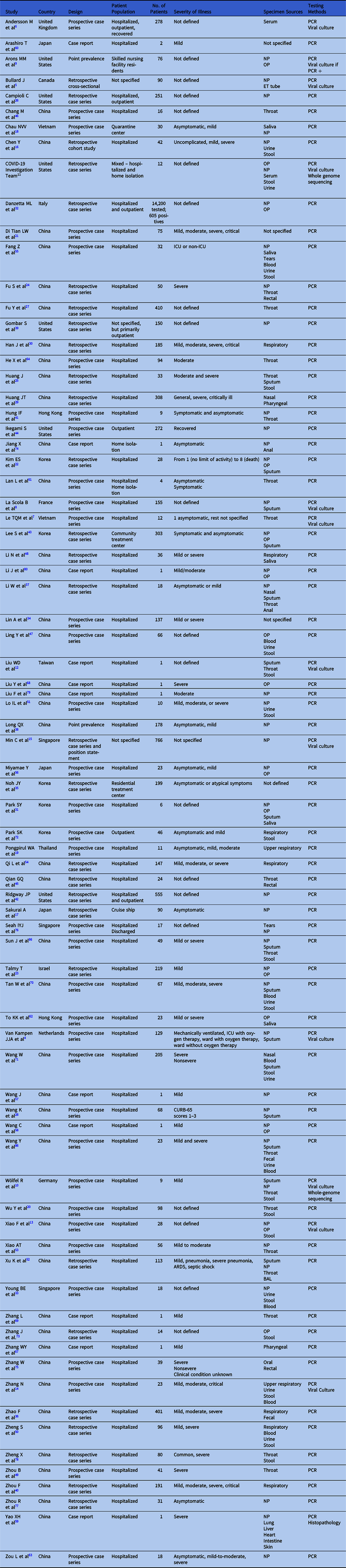

In total, 77 studies and reports were eligible for inclusion: prospective case series (N = 35), retrospective case series (N = 28), case reports (N = 11), point prevalence survey (N = 2), and position statements (N = 1) (Table 1). Overall, 59 of these studies were peer reviewed, 6 were from preprint servers, and 13 were research letters or letters to the editor. Moreover, 70 studies described hospitalized patients. All studies reported PCR-based assessments of viral shedding; 12 studies reviewed reported viral culture data.Reference van Kampen, van de Vijver and Fraaij4-Reference Ong Wei Min15 Also, 30 studies reported PCR testing of nonrespiratory specimens.

Table 1 Summary of Literature Included in Review of SARS-CoV-2 Viral Shedding

Note. NP, nasopharyngeal; OP, oropharyngeal; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; ET, endotracheal.

Duration of Viral RNA Shedding

Overall, 77 reports included data on viral RNA shedding by PCR.Reference van Kampen, van de Vijver and Fraaij4-Reference Li, Zhang, Liu and Song80 Box 1 summarizes the key points of viral shedding duration. The duration of viral RNA shedding ranged from a minimum of 1 dayReference van Kampen, van de Vijver and Fraaij4,Reference Le, Takemura and Moi7,Reference Di Tian and Xiankun21,Reference Young, Ong and Kalimuddin33,Reference Chang and Yuan46 to a maximum of 83 days.Reference Li, Wang and Lv48 Intermittent PCR positivity did occur through day 92 from symptom onset in 1 case report—that patient had previously tested negative at day 72 followed by repeat positive PCR.Reference Wang, Hang and Wei57 In a study of 56 serially tested hospitalized patients with mild-to-moderate disease, 66.1% of NP and OP swabs were still positive at 3 weeks. Positivity rates then declined weekly and all PCR tests were negative by week 6.Reference Ong Wei Min15 Based on the 28 studies that provided sufficient data (Appendix Table 1 online), the pooled median duration of RNA shedding from respiratory samples was 18.4 days (95% CI, 15.5–21.3). High heterogeneity was observed among these studies (I2 = 98.87%; P < .01).

Box 1. Brief Summary of Available Literature on SARS-CoV-2 Shedding

We reviewed shedding data for patients with mild-to-moderate illness. Based on parametric regression modeling, Sun et alReference Sun, Xiao and Sun66 concluded that detection of viral RNA in throat swabs beyond 50 days post symptom onset in patients with mild illness would be a low probability event occurring beyond the 95th percentile. Despite this calculation, there are case reports of patients with viral RNA shedding ≥45 days from symptom onset.Reference Li, Wang and Lv48,Reference Wang, Xu and Zhang58,Reference Zhang, Yu, Huang and Zeng67-Reference Zhang, Li, Zhou, Wang and Zhang69,Reference Zheng, Chen and Deng78,Reference Li, Zhang, Liu and Song80 Among all studies we reviewed, the longest duration of PCR positivity from a NP swab of a patient with mild illness was 92 days after symptom onset.Reference Wang, Hang and Wei57 The pooled median duration of viral RNA shedding from respiratory sources among patients with mild-to-moderate illness, based upon 10 studies that reported sufficient data (Appendix Table 1 online), was 17.2 days (95% CI, 14.0– 20.5). Again, there was high heterogeneity among these studies (I2 = 95.64%; P < .01).

There were multiple reports of patients with intermittently positive PCR results from respiratory specimens.Reference Sakurai, Sasaki and Kato17,Reference Di Tian and Xiankun21,Reference Huang, Mao and Li25,Reference Fu, Han and Zhu27,Reference Wang, Zhang and Sun28,Reference Lo, Lio and Cheong51,Reference Miyamae, Hayashi and Yonezawa56-Reference Wang, Xu and Zhang58,Reference Liu, Cai and Huang79,81 Although not consistently defined, cessation of shedding was most often described as 2 consecutive negative PCR results ≥24–48 hours apart.Reference Di Tian and Xiankun21,Reference Talmy, Tsur and Shabtay23,Reference Huang, Mao and Li25,Reference Long, Tang and Shi38,Reference Lo, Lio and Cheong51,Reference Miyamae, Hayashi and Yonezawa56,Reference Wang, Xu and Zhang58,81 Tests were frequently done in anticipation of discharge from the hospital.Reference Wang, Hang and Wei57,81 One report estimated that 26%–49% of patients were positive again after a negative test, but in other studies re-positivity varied between 3% and 35%.Reference Sakurai, Sasaki and Kato17,Reference Di Tian and Xiankun21,Reference Huang, Mao and Li25,Reference Fu, Han and Zhu27,Reference Wang, Zhang and Sun28,Reference Lo, Lio and Cheong51,Reference Miyamae, Hayashi and Yonezawa56,81 Wang et alReference Wang, Hang and Wei57 described a case report of a patient that was discharged 75 days after illness onset following 3 consecutive negative tests. The patient then tested positive on days 82 and 92, followed by negative PCR tests on days 101 and 105.Reference Wang, Hang and Wei57 Another case report described a woman with mild COVID-19 who intermittently tested positive by NP PCR swabs for 72 days from disease onset despite developing IgM and IgG antibodies on day 38.Reference Wang, Xu and Zhang58

Wölfel et alReference Wolfel, Corman and Guggemos10 observed that the pharyngeal rate of detection was highest in the first 5 days of symptom onset and then decreased.Reference Wolfel, Corman and Guggemos10 NP swabs may have a higher rate of detection than OP swabs, but they were only compared in 2 of the studies included in this review.Reference Zou, Ruan and Huang63,Reference Wang, Xu and Gao71 Negative upper-tract specimens may not correlate with lower-tract specimens, though the significance of these findings is not well understood. In a postmortem analysis of a patient whose NP sample tested PCR negative, lung tissue was PCR positive and histology revealed coronavirus particles in bronchiolar epithelial cells.Reference Yao, He and Li59

Some studies included data for presymptomatic or asymptomatic patients and observed that PCR positivity can occur as early as 5 days prior to symptom onset.Reference Arons, Hatfield and Reddy9,Reference Wolfel, Corman and Guggemos10,Reference Arashiro, Furukawa and Nakamura60,Reference Lan, Xu and Ye61 Multiple case series reported that the viral load of asymptomatic patients are as high as those with symptoms.Reference Arons, Hatfield and Reddy9,Reference Wolfel, Corman and Guggemos10,Reference To, Tsang and Leung62 In one case series, the asymptomatic individual in a family cluster had similar viral RNA loads in nasal and throat swabs to those of symptomatic family members.Reference Zou, Ruan and Huang63 The majority of the subjects in this case series converted to a negative PCR by day 18.Reference Zou, Ruan and Huang63

In addition, 5 studies included saliva samples.Reference Chau, Thanh Lam and Thanh Dung18,Reference Park, Yun and Shin31,Reference Li, Wang and Lv48,Reference Fang, Zhang, Hang, Ai, Li and Zhang55,Reference To, Tsang and Leung62 In a series of 13 patients with mild disease, viral RNA load was highest in saliva in the first week of illness, but 3 of the patients still had detectable viral load in their saliva at day 20 of illness.Reference Li, Wang and Lv48 In another series, PCR turned negative in the saliva of 13 mildly ill patients before nasal swab PCR: an average (±SD) of 13.33 ± 5.27 days and 15.67 ± 6.68 days, respectively.Reference Fang, Zhang, Hang, Ai, Li and Zhang55 In the same study, the average duration of positive PCR in sputum was shorter in non-ICU patients than ICU patients, who were positive for an average (SD) of 16.5 ± 6.19 days.Reference Fang, Zhang, Hang, Ai, Li and Zhang55

Predictors of extended duration of viral RNA shedding in respiratory samples

The most frequently identified predictor of prolonged viral RNA shedding was disease severity. Patients with severe disease have been observed to shed RNA for longer and have higher viral RNA loads at symptom onset followed by a gradual decline in viral RNA 3 weeks after symptom onset.Reference Huang, Ran and Lv29,Reference Danzetta, Amato and Cito32,Reference Zheng, Fan and Yu50,Reference Xiao, Tong and Zhang53,Reference He, Lau and Wu64,Reference Wang, Zhang and Sang65 Based on 10 studies, the pooled median duration of viral RNA shedding from respiratory samples in patients with severe illness was 19.8 days (95% CI, 16.2–23.5) (Appendix Table 1 online). Again, significant high heterogeneity exists (I2 = 96.42%; P < .01). In one cohort of patients, the median duration (SD) of positive NP PCRs was 22.25 (±3.62) days in patients admitted to the ICU, compared to 15.67 (±6.68) days in non-ICU patients.Reference Fang, Zhang, Hang, Ai, Li and Zhang55 Sun et alReference Sun, Xiao and Sun66 also observed prolonged duration of RNA shedding from NP swabs in those with severe illness compared to those with mild disease, with median durations of 33.5 days and 22.7 days, respectively.

Predictors of severe disease and duration of shedding ≥15 days in hospitalized patients included older age, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and diabetes mellitus.Reference Sakurai, Sasaki and Kato17,Reference Fu, Han and Zhu27,Reference Zheng, Fan and Yu50,Reference Xu, Chen and Yuan52,Reference Xiao, Tong and Zhang53,Reference To, Tsang and Leung62 Gender was not consistently identified as a risk factor for severe disease or prolonged shedding but comparisons were limited by small sample sizes.Reference Ling, Xu and Lin47,Reference Zhou, She, Wang and Ma49,Reference Xu, Chen and Yuan52,Reference Qi, Yang and Jiang54,Reference To, Tsang and Leung62

Viral RNA shedding in nonrespiratory samples

A subset of studies presented PCR data from both respiratory and fecal samples.Reference Wolfel, Corman and Guggemos10-Reference Zhang, Gong and Meng14,Reference Chen, Chen and Deng16,Reference Wu, Guo and Tang20,Reference Fu, Fu and Song24,Reference Huang, Mao and Li25,Reference Young, Ong and Kalimuddin33,Reference Zhao, Yang, Wang, Li, Liu and Liu36,Reference Li, Su and Zhi37,Reference Qian, Chen and Lv45,Reference Ling, Xu and Lin47,Reference Zheng, Fan and Yu50,Reference Lo, Lio and Cheong51,Reference Fang, Zhang, Hang, Ai, Li and Zhang55,Reference Wang, Zhang and Sang65,Reference Sun, Xiao and Sun66,Reference Tan, Lu and Zhang70-Reference Zhang, Du and Li75,Reference Zheng, Chen and Deng78 Rectal/stool PCR pooled median duration of positivity based on 5 studies was 22.1 days (95% CI, 14.4–29.8; I2 = 95.86%; P < .01). Stool PCR positivity has been observed to lag behind both PCR positivity of pharyngeal specimens and symptom improvement and even may become positive after the OP PCR has become negative.Reference Chen, Chen and Deng16 RNA replication in the stool was observed ≥2 weeks after symptom onset.Reference Wolfel, Corman and Guggemos10,Reference Wu, Guo and Tang20,Reference Zheng, Fan and Yu50,Reference Lo, Lio and Cheong51,Reference Zhang, Wang and Xue73 In one study, the number of PCR-positive stool samples increased between the first and third weeks of illness, with a median time to detection in the stool of 19–22 days.Reference Zheng, Fan and Yu50,Reference Tan, Lu and Zhang70 Based on the limited data available thus far, illness severity does not seem to impact stool RNA detection, as similar durations of RNA shedding in the stool have been observed in mild and severe illness.Reference Chen, Chen and Deng16 Park et alReference Park, Lee and Park72 detected SARS-CoV-2 RNA in stool 50–55 days after initial diagnosis of asymptomatic or mild SARS-CoV-2 illness. In this study, people with higher viral loads were more likely to have viral RNA in the stool.Reference Park, Lee and Park72 However, stool shedding was not consistently observed, and some studies showed that virus was detectable in only 35%–59% of patients screened.Reference Zheng, Fan and Yu50,Reference Zhang, Du and Li75

Data for serum and blood are limited but are evolving. Among studies reporting serum or blood testing, viral RNA was detected in 30%–87.5% of patients with COVID-19, though a smaller study did not detect viral RNA in any of the 14 patients tested.Reference Ling, Xu and Lin47,Reference Zheng, Fan and Yu50,Reference Fang, Zhang, Hang, Ai, Li and Zhang55,Reference Zhang, Du and Li75,Reference Hogan, Stevens and Sahoo82 The ability to detect RNA in blood and serum may be reflective of disease severity.Reference Fang, Zhang, Hang, Ai, Li and Zhang55,Reference Hogan, Stevens and Sahoo82 Virus was detected by PCR for longer in blood samples of ICU patients [14.63 days (±5.88 SD)] compared to non-ICU patients [10.17 days (±6.13 SD)].Reference Fang, Zhang, Hang, Ai, Li and Zhang55

Correlation between viral culture and PCR

In total, 12 studies also included both PCR and viral culture information.Reference van Kampen, van de Vijver and Fraaij4-Reference Ong Wei Min15 Sequential viral cultures were not performed in all studies, which is a key limitation. Growth of SARS-CoV-2 on viral respiratory culture was reported ranging from 6 days before symptom onset through day 20 after symptom onset.Reference van Kampen, van de Vijver and Fraaij4,Reference Bullard, Dust and Funk5,Reference Arons, Hatfield and Reddy9,Reference Wolfel, Corman and Guggemos10 A position statement published in Singapore reported that viable cultured virus was not isolated after day 11.Reference Ong Wei Min15 Culture data suggest that the duration of shedding of viable virus may vary according to illness severity. In a study of patients with moderate-to-severe illness, Van Kampen et alReference van Kampen, van de Vijver and Fraaij4 found the median duration of shedding viable virus was 8 days (IQR, 5–11 days; range, 0–20 days) with the probability of detecting virus <5% after 15.2 days.Reference van Kampen, van de Vijver and Fraaij4 In contrast, 4 studies of mildly ill patients did not find viable virus past day 8 or 9 of illness, but viral culture was not consistently reattempted.Reference Bullard, Dust and Funk5,Reference Arons, Hatfield and Reddy9-Reference Team11 Liu et alReference Liu, Chang and Wang12 described a patient with mild disease whose sputum viral culture was positive on day 18, but continued to have viral RNA detection until day 63, 45 days longer than detection of viable virus.

The correlation of SAR-CoV-2 viral loads and PCR cycle thresholds (Ct) values with isolation of viable virus is a topic of interest. The Ct value upper bound cutoff that determined a positive PCR was inconsistent among studies reporting this threshold, though most reported positive values at ≤35 or ≤40.Reference Zhou, She, Wang and Ma49-Reference Xu, Chen and Yuan52,Reference Qi, Yang and Jiang54,Reference Park, Lee and Park72,Reference Zhou, Li and Chen77 Bullard et alReference Bullard, Dust and Funk5 compared PCR Ct value with culture positivity and found that the ability to isolate virus in culture was reduced when Ct value was ≥24. They reported that the odds ratio for infectivity decreased by 32% for every 1 point increase in the Ct value.Reference Bullard, Dust and Funk5 La Scola et alReference La Scola, Le Bideau and Andreani8 report significant correlation between Ct value and culture positivity rates. Positive cultures occurred in all samples with Ct values 13–17 but culture positivity decreased to 12% at a Ct value of 33.Reference La Scola, Le Bideau and Andreani8 Isolating virus in culture with positive PCR samples containing viral loads <106 copies per milliliter is less likely to be successful.Reference van Kampen, van de Vijver and Fraaij4,Reference Wolfel, Corman and Guggemos10

Limited data exist regarding SARS-CoV-2 cultures in nonrespiratory specimens. Viral culture was attempted in serum samples of PCR-positive patients without growth.Reference Andersson, Arancibia-Carcamo and Auckland6 Viral stool cultures have yielded mixed results. Wölfel et alReference Wolfel, Corman and Guggemos10 performed viral culture of 13 stool samples from 4 different patients with mild disease on days 6–12 without growth, despite RNA detected in the stool through day 21. Viable virus was detected in the stool of a critically ill patient on day 19 with negative cultures beyond this despite a positive NP/OP PCR through day 28.Reference Wolfel, Corman and Guggemos10 Of 7 studies that processed urine samples, 2 reported detecting viable virus by culture.Reference Team11,Reference Ling, Xu and Lin47,Reference Zheng, Fan and Yu50,Reference Lo, Lio and Cheong51,Reference Fang, Zhang, Hang, Ai, Li and Zhang55,Reference To, Tsang and Leung62,Reference Wang, Xu and Gao71 Also, 2 studies of patients with positive respiratory PCR samples attempted to culture virus from tears, but they yielded no growth.Reference Fang, Zhang, Hang, Ai, Li and Zhang55,Reference Seah, Anderson and Kang76

Discussion

We summarized available data on duration of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA shedding, isolation of viable virus, and the impact of infection severity on shedding duration. The pooled median duration of RNA shedding from respiratory samples of subjects was 18.4 days (95% CI, 15.54–21.3). In general, the highest viral loads occur within 1–2 weeks of illness onset, regardless of symptoms, with a subsequent gradual decline. However, several studies described PCR positivity beyond 2 weeks. Patients with more severe illness shed viral RNA for a longer period of time, with a pooled median duration of 19.8 days (95% CI, 16.2–23.5), compared to 17.2 days (95% CI, 14.0–20.5) for mild illness. Although these pooled medians should be interpreted with caution given the high heterogeneity of the studies and overlapping confidence intervals, viral culture data appear to support this conclusion. In reviewed studies, viable virus from respiratory cultures was not recovered past day 9 of illness for mildly ill patients but was cultured from severely ill patients through day 20.Reference van Kampen, van de Vijver and Fraaij4,Reference Bullard, Dust and Funk5,Reference Arons, Hatfield and Reddy9,Reference Wolfel, Corman and Guggemos10

Interpreting positive PCR samples beyond 2–3 weeks of illness is complex. Potential explanations for these intermittently negative PCR tests include a viral load below the detection limit of the assay, specimen source, quality of specimen collection, timing of specimen collection or reinfection.Reference Prinzi83,Reference Bullis, Crothers, Wayne and Hale84 Although viral culture positivity may also not correlate perfectly with transmissibility, the correlation between culture data and Ct thresholds may help predict infectiousness. Further data are needed to understand the correlation between transmission risk, culture positivity and Ct thresholds. The studies that examined viral culture were limited by small size, inclusion of patients with mostly mild illness, and lack of serial cultures on all patients. Isolation of viable virus in respiratory samples correlates with the timing of peak viral loads which occur within 1–2 weeks of illness onset. Only 1 study reported culturing viable virus from a respiratory sample beyond the second week of illness. Based on this information, it seems more likely that a positive PCR past 2–3 weeks of illness represents shedding of nonviable virus. Although the pooled median viral RNA shedding duration from patients with mild-to-moderate and severe disease do not differ greatly, reports of positive viral cultures through day 20 in severely ill patients support the potential for a prolonged infectious period for sicker patients. In addition, viable virus has been recovered from stool cultures, but further studies are needed to determine the implications for person-to-person spread.

Our review supports the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) interim guidance, which recommends maintaining transmission-based precautions for 10 days after symptom onset in asymptomatic or mildly ill patients and for 20 days in severely ill patients.85 The decision to extend the duration of transmission-based precautions is complicated given the potentially profound impact on patients and their families, hospital systems, and public health. Prolonged home isolation may lead to longer periods of unemployment, social separation, and feelings of isolation. In the hospital, the supply of personal protective equipment, staff allocation, availability of patient beds, and the health system budget are impacted by the duration of isolation for patients with COVID-19. That said, aggressive infection control measures are required in the setting of an outbreak to control the virus and to avoid overwhelming healthcare systems.

In calculating the pooled median duration of shedding, we identified a significantly high degree of heterogeneity between studies. In a standard meta-analysis, we would not report a pooled measure of association when heterogeneity was high. However, the pooled median is not intended to inform our knowledge of causality or effect size but, rather, to best inform the policy decisions that currently must be made on the very limited data available at this time in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Factors contributing heterogeneity may include the variable timing of sample collection for PCR or viral culture, Ct threshold, sample types, SARS-CoV-2 genotype, and host factors such as pharmacotherapy, comorbidities, and disease severity. We noted broad variability in the definitions of disease severity applied. Although no formal definitions existed initially, the National Commission of China developed a classification scheme for mild, moderate, and severe illness that include specific clinical variables.Reference Tan, Lu and Zhang70 The National Institutes of Health and World Health Organization have since developed similar severity scales also.85,Reference Wang, Zhang and Sang86 Going forward, these definitions will facilitate the conduct of generalizable studies of viral dynamics.

This comprehensive review details the evidence available to date pertaining to SARS-CoV-2 viral dynamics. Although PCR positivity can be prolonged, culture data suggest that virus viability is typically shorter in duration. Continued reporting of viral shedding data via PCR and viral culture with improved standardization in methods and definitions, in coordination with transmission data, will facilitate evidence-based decision making for the infection control and public health measures necessary to control the pandemic.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2020.1273