Appropriate antibiotic prescribing is an important clinical and public health goal because inappropriate antibiotic use is associated with increased risk of treatment failure, adverse events, antibiotic resistance, and healthcare costs.1–Reference Shehab, Patel, Srinivasan and Budnitz6 Uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs) account for ∼10.5 million ambulatory visits annually in the United States, and they are a common reason for outpatient antibiotic use in otherwise healthy females.Reference Flores-Mireles, Walker, Caparon and Hultgren7 The international clinical practice guidelines for treatment of uncomplicated UTI in women, updated in 2010 by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, recommend several first-line antibiotic agents and durations based on efficacy results from randomized clinical trials and known prevalence of antibiotic resistance.Reference Gupta, Hooton and Naber8 Guidelines recommend empiric use of nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) as first-line agents, reserving fluoroquinolones for infections other than uncomplicated UTIs because the risk of rising antibiotic resistance and serious adverse events generally outweighs the benefits.Reference Kobayashi, Shapiro, Hersh, Sanchez and Hicks9,Reference Sanchez, Babiker, Master, Luu, Mathur and Bordon10 However, most antibiotic prescriptions for uncomplicated UTIs are suboptimal because they are written for nonrecommended agents and durations.Reference Durkin, Keller and Butler11,Reference Grigoryan, Zoorob, Wang and Trautner12

Given the high burden of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing among women with uncomplicated UTIs in the United States, research on contemporary patterns of treatment is needed to identify disparities in appropriate antibiotic use. Knowledge about current practice patterns is needed to inform antimicrobial stewardship programs, which could ultimately enhance outpatient antibiotic prescribing and improve health outcomes. It is important to identify settings characterized by higher inappropriate antibiotic prescribing; such settings could be targets for interventions designed to improve guideline adherence.

The rural health disparity has been a recent focus in the United States, and its improvement is a priority of the Department of Health and Human Services.Reference Hall, Kaufman and Ricketts13 Previous studies on respiratory tract and pediatric infections have identified associations between inappropriate antibiotic prescribing and individual- and provider-level factors, including geographic region, rural–urban status, and provider specialty.Reference Barlam, Soria-Saucedo, Cabral and Kazis14,Reference Fleming-Dutra, Demirjian, Bartoces, Roberts, Taylor and Hicks15 However, no large-scale studies have evaluated rural–urban differences in inappropriate outpatient antibiotic prescribing for UTIs.Reference Shapiro, Hicks, Pavia and Hersh16

To address this knowledge gap, we analyzed rural–urban differences in real-world antibiotic treatment patterns for the outpatient treatment of uncomplicated UTIs in a large cohort of US commercially insured, premenopausal women. We explored rural–urban differences in temporal trends and risk of inappropriate antibiotic use by agent and duration, both overall and within subgroups, comparing to current IDSA guidelines to determine prescription appropriateness.

Methods

Data source

The IBM MarketScan commercial database (2006–2015) includes healthcare data for millions of commercially insured individuals from all 50 US states and the District of Columbia. The database includes deidentified longitudinal paid physician, pharmacy, and hospital claims data linked to demographic information from large employers and health plans that insure employees, their spouses, and dependents.Reference Hansen17 These data have been used widely in health services and pharmacoepidemiologic research due to their large quantity, national representation, longitudinal structure, and comprehensive capture of outpatient services, inpatient services, and outpatient drug claims. Drug information represents prescriptions filled at a pharmacy. Our study using deidentified data was considered exempt from human subject review by the Institutional Review Board at Washington University.

Study design and population

We constructed a cohort of women diagnosed and treated for uncomplicated UTI, defined in accordance with criteria outlined in current guidelines, using methods previously described.Reference Gupta, Hooton and Naber8,Reference Kobayashi, Shapiro, Hersh, Sanchez and Hicks9 The cohort included premenopausal women aged 18–44 years who received an outpatient diagnosis of uncomplicated UTI (ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 595.0, 595.9, or 599.0) with an accompanying antibiotic prescription from April 1, 2011, to June 30, 2015. The index date was defined as the date of a filled oral prescription for an antibiotic with activity against common uropathogens, which occurred on the day of or after the diagnosis of uncomplicated UTI. The 180-day baseline period prior to the index date was used to identify exclusion criteria and covariates. To ensure adequate ascertainment of medical history, women without continuous enrollment in a medical plan or prescription drug coverage during the 180-day baseline period were excluded. To meet the definition of uncomplicated UTI,Reference Gupta, Hooton and Naber8 women were excluded if they received diagnoses or prescription medications during the 180-day baseline period for pregnancy, urinary comorbidities or abnormalities, pyelonephritis, diabetes, systemic autoimmune conditions, spinal cord injuries, or hematologic or solid-organ malignancies (Supplementary Tables 1–3 online). To restrict the study population to women with community-acquired UTIs, women were excluded if they had been hospitalized within 90 days prior to the index date. To restrict the study population to new users of antibiotics, women were excluded if they had received an antibiotic in the 30 days prior to the index date or if they had an infection in the 30 days prior to or on the index date (Supplementary Table 4 online).

Rural–Urban definition

We classified individuals as urban if the primary beneficiary resided in a metropolitan statistical area; otherwise, the individual was classified as rural. IBM mapped the 5-digit postal zip code of each primary beneficiary’s residence according to the US Census Bureau geographical mapping classification, which requires each metropolitan statistical area to have at least 1 urbanized area of ≥50,000 inhabitants and includes their nearby communities if they are socioeconomically joined together.Reference Hansen17,18

Antibiotic outcome definitions

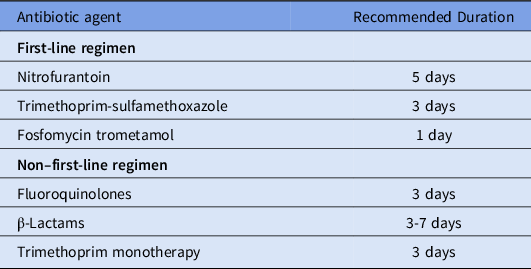

Table 1 presents the IDSA guideline-recommended first-line and non–first-line antibiotic agents as well as the recommended duration for treatment of uncomplicated UTI.Reference Gupta, Hooton and Naber8 In accordance with these guidelines, we separately classified antibiotic prescriptions as appropriate or inappropriate based on antibiotic agent and duration, as described in our previous work.Reference Durkin, Keller and Butler11 We classified first-line agents (nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole [TMP-SMX], and fosfomycin) as appropriate and non–first-line agents (fluoroquinolones and β-lactams) as inappropriate. In accordance with current guidelines, and because TMP monotherapy use was rare, we considered TMP monotherapy to be equivalent to TMP-SMX. For individuals who received multiple UTI-related antibiotic prescriptions, we classified the prescription as appropriate if they received only 1 first-line agent and inappropriate if they received multiple first-line agents or only non–first-line agents (on the same date). We classified antibiotic prescriptions as appropriate duration when the duration matched the recommended duration per current guidelines (Table 1).Reference Gupta, Hooton and Naber8 Specifically, the following regimens were classified as appropriate duration: nitrofurantoin 5-day regimen, TMP-SMX (including TMP monotherapy) 3-day regimen, fosfomycin 1-day regimen, fluoroquinolones 3-day regimen, and β-lactams 3–7-day regimens. All other regimens were classified as inappropriate duration. For individuals who received multiple UTI-related antibiotic prescriptions, we classified the duration as appropriate if each regimen was for the recommended duration; otherwise, we classified the duration as inappropriate if the regimen was not the recommended duration.

Table 1. Guideline-Recommended Antibiotic Therapy for Acute Uncomplicated Cystitis by Antibiotic Agent and Durationa

a Adapted from the 2011 IDSA clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis in women.Reference Gupta, Hooton and Naber8

Covariate assessment

Covariate information was collected during the 180-day baseline period on age, year, state, geographic region, provider type, health insurance plan type, receipt of urinalysis at index, receipt of urine culture at index, and type of outpatient encounter (in-person or laboratory only).

Statistical analysis

We summarized the distribution of antibiotic prescription agents and durations by rural–urban status. We plotted state-level maps of the proportion of antibiotic prescriptions with inappropriate agents or durations, stratified by rural–urban status. We calculated the standardized mean differences of baseline covariates to characterize imbalances of observed covariates.Reference Yang and Dalton19 To examine the relationship between rural–urban status and inappropriate antibiotic receipt, we used modified Poisson regression to estimate risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), adjusting for age, year, geographic region, provider type, receipt of urinalysis at index, and receipt of urine culture at index.Reference Zou20 We built a separate model for each outcome (ie, inappropriate agent and inappropriate duration). In sensitivity analyses, we also adjusted for health insurance plan type.

To describe temporal trends in inappropriate antibiotic use by calendar quarter, we used logistic regression models to generate adjusted estimates of the proportion of rural versus urban patients who received inappropriate antibiotic agents or durations. Calendar quarter was treated as a categorical variable in the models to relax the assumption of linearity. We plotted the adjusted estimates, which are population marginal means that account for changes over time in age, geographic region, receipt of urinalysis at UTI diagnosis, receipt of urine culture at UTI diagnosis, and provider specialty. Trend lines were calculated as a smoothed conditional mean of the quarterly adjusted estimates. We performed subgroup analyses by stratifying models by antibiotic agent (duration outcome only), geographic region, and provider type.

Results

Cohort characteristics

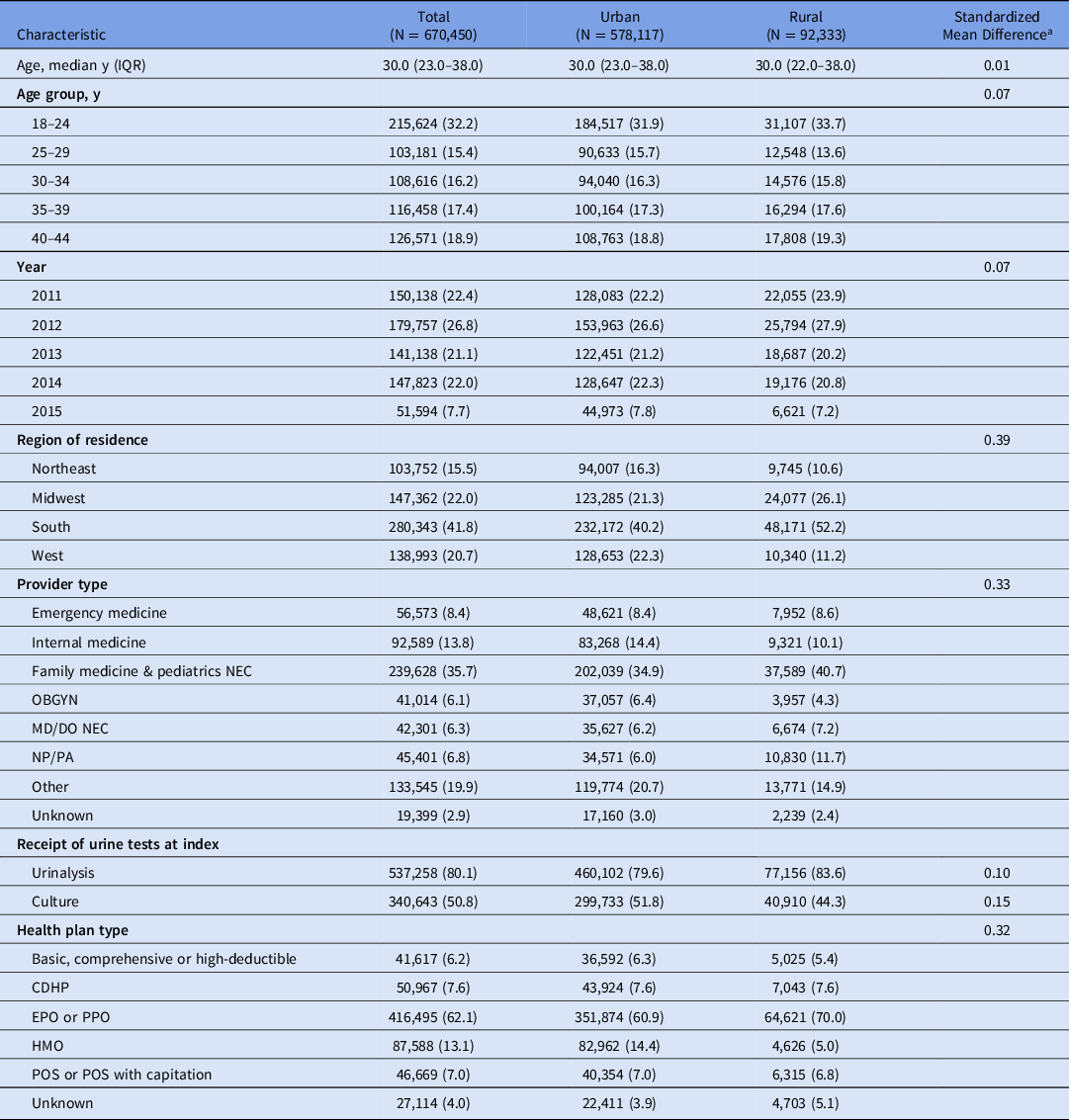

We identified 670,450 women who met study eligibility criteria from an original 1,349,276 women (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). Most women (86.2%) were from urban areas, and 13.8% were from rural areas. Table 2 presents characteristics of the study population stratified by rural–urban status. Rural and urban women had a similar median age (30 years). Compared to urban women, rural women were more likely to reside in the South (52.2% vs 40.2%) and the Midwest (26.1% vs 21.3%), and they were less likely to reside in the Northeast (10.6% vs. 16.3%) or the West (11.2% vs 22.3%). The distribution of provider type differed by rural–urban status. Compared to urban women, rural women were similarly likely to have been diagnosed with UTI by an emergency medicine physician, were less likely to have been diagnosed by internal medicine or obstetrics/gynecology (OBGYN) physicians, and were more likely to have been diagnosed by family medicine or pediatric physicians or nonphysicians. Patterns of urine testing at index date differed by rural–urban status because rural women were more likely than urban women to be tested with a urinalysis (83.6% vs 79.6%) but less likely to be tested with a urine culture (44.3% vs 51.8%).

Table 2. Characteristics of the Study Population

Note: CDHP, consumer-driven health plans; DO, doctor of osteopathic medicine; EPO, exclusive provider organization; HMO, health maintenance organization; IQR, interquartile range; MD, medical doctor; NEC, not elsewhere classified; NP, nurse practitioner; OBGYN, obstetrics and gynecology; PA, physician’s assistant; POS, point of service; PPO, Preferred provider organization.

a Standardized mean differences <0.10 indicate balance in observed covariates between rural and urban women.

Risk of receipt of inappropriate antibiotic agent

Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 5 (online) present the distribution of antibiotic prescriptions by agent, overall and by rural–urban status. The most commonly prescribed agents were fluoroquinolones and the first-line agents TMP-SMX and nitrofurantoin. A similar proportion of antibiotic prescriptions were inappropriate agents for rural (45.9%) and urban (46.9%) women, with similar percentages for individual agents. The use of inappropriate agents was similar between rural and urban women: fluoroquinolones (41.0% vs 41.7%), β-lactams (4.8% vs 5.0%), multiple agents without first-line agents (0.1%), and multiple agents with ≥2 first-line agents (0.1%). Rural women received more TMP-SMX (33.3% vs 26.4%) and less nitrofurantoin (20.8% vs 26.7%).

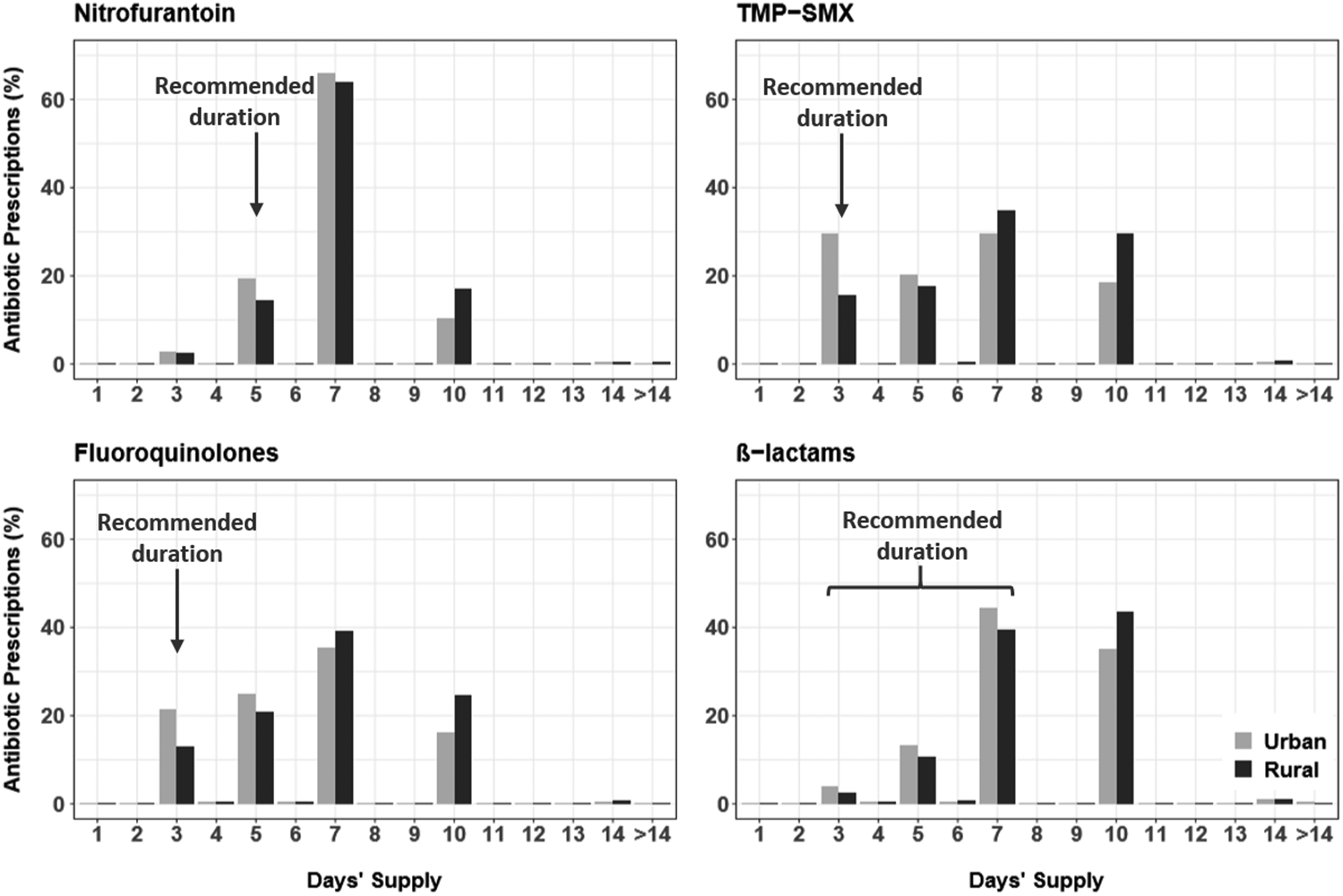

Fig. 1. Distribution of the antibiotic prescription duration by rural–urban status for recipients of nitrofurantoin (153,098 urban and 19,079 rural women), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX; 152,053 urban and 30,568 rural women), fluoroquinolones (240,982 urban and 37,854 rural women), and β-lactams (29,023 urban and 4,411 rural women).

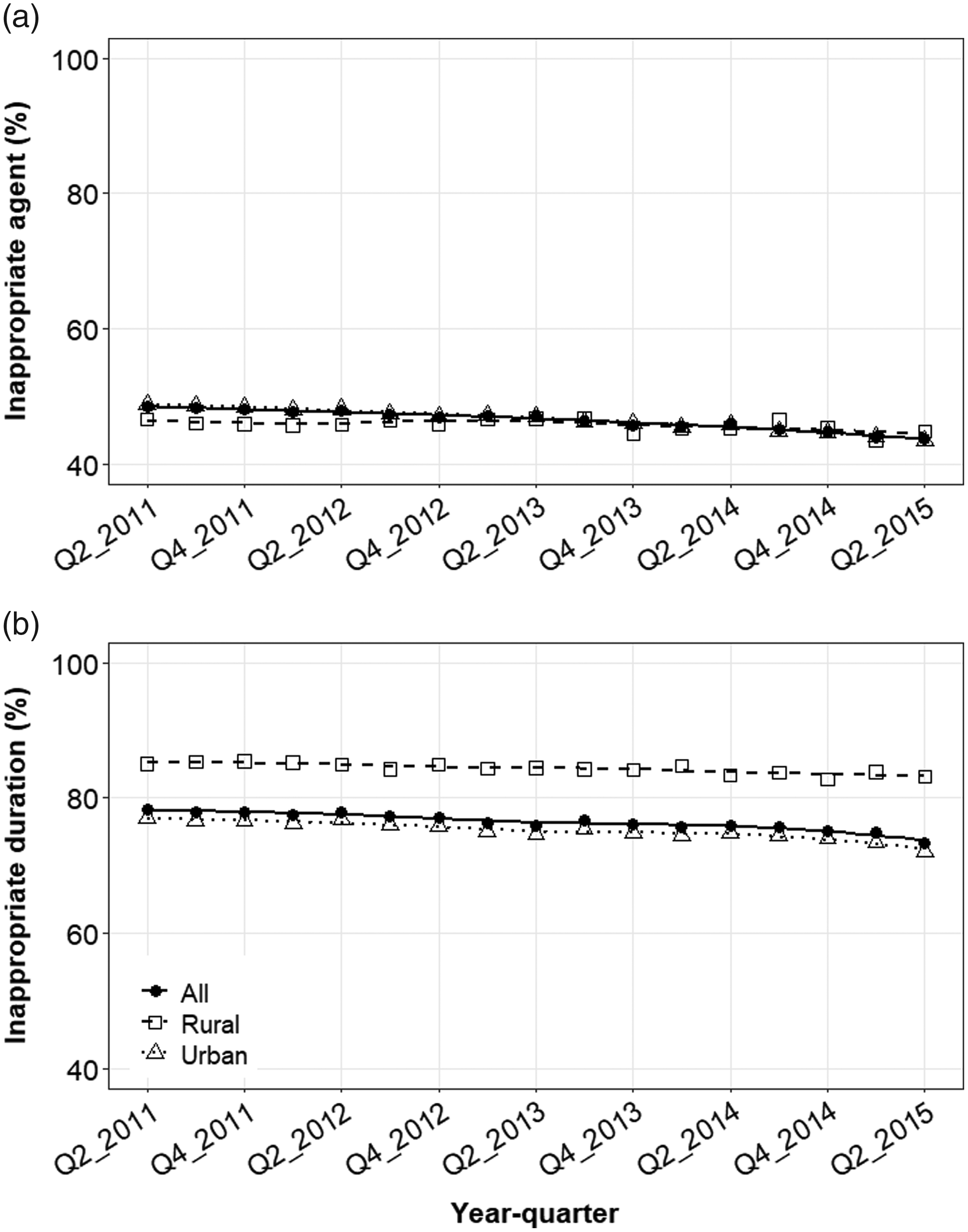

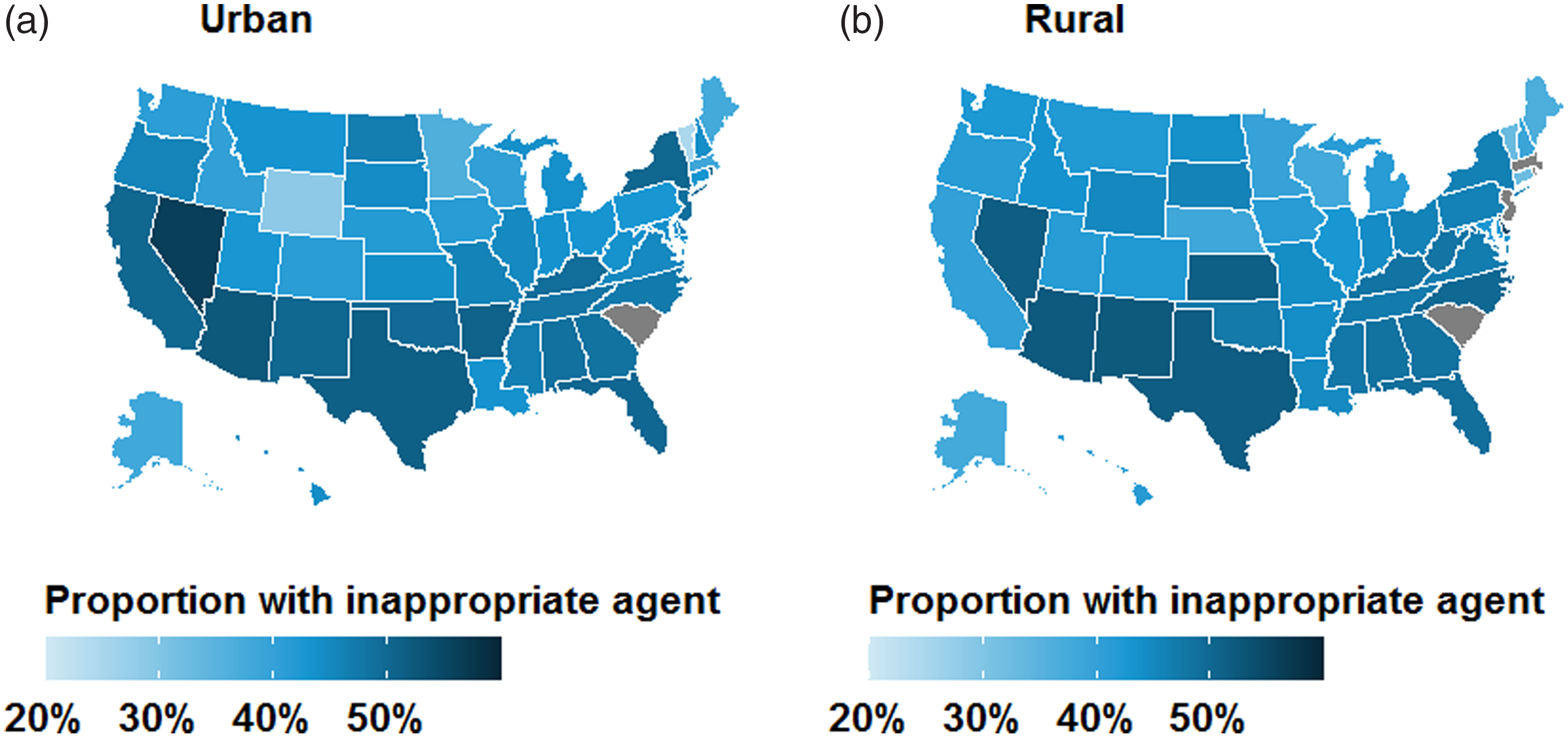

Over the study period, the proportion of patients that received inappropriate agents by quarter declined from 48.5% in mid-2011 to 43.7% in mid-2015 (Fig. 2A). The use of inappropriate agents declined slightly among both urban (from 48.8% to 43.5%) and rural women (from 46.6% to 44.8%). State-level maps illustrated that women were more likely to receive inappropriate agents in the South and West regions, irrespective of rural–urban status (Fig. 3). Subgroup analyses demonstrated that rural–urban differences in inappropriate agent use varied over time within geographic regions (eg, Northeast and West) and provider specialties (eg, internal medicine and OBGYN) (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3 online). For example, among internal medicine physicians, inappropriate agent use was higher in rural areas in 2011, was similar by 2013, and was higher again by 2015.

Fig. 2. Mean quarterly use of UTI-related antibiotic prescriptions with (A) inappropriate agents or (B) inappropriate durations in the outpatient setting by rural–urban status. Quarterly estimates were adjusted for age, geographic region, provider type, receipt of urinalysis at index, and receipt of urine culture at index. Trend lines represent smoothed conditional means.

Fig. 3. Geographic distribution of antibiotic prescriptions with inappropriate agents for treatment of uncomplicated UTI in the outpatient setting by rural–urban status: (A) urban and (B) rural. Results are unadjusted and are not presented for grey states due to business agreement with IBM.

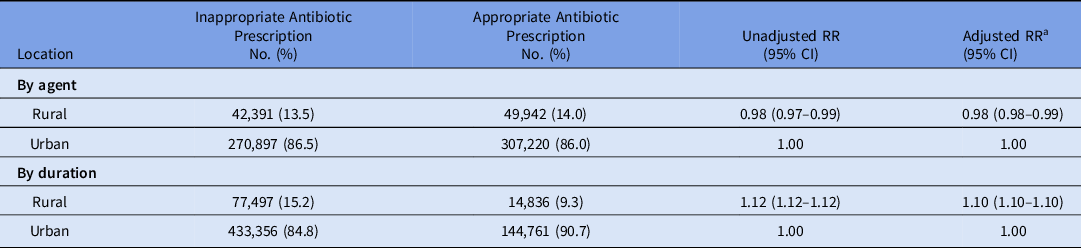

In the multivariable model, rural women had a slightly lower risk of receipt of an inappropriate antibiotic agent (adjusted RR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.98–0.99) compared to urban women (Table 3). In the sensitivity analysis, results did not change appreciably in the model that also accounted for health insurance plan type. The association between rural–urban status and inappropriate agent varied across geographic regions (Supplementary Fig. 4 online). Compared to urban women, risk of receipt of an inappropriate agent among rural women was similar in the South and Midwest but was lower in the West (adjusted RR 0.92, 95% CI, 0.90–0.95) and the Northeast (adjusted RR 0.94, 95% CI, 0.92–0.97). The association between rural–urban status and inappropriate agent also varied across provider specialties (Supplementary Fig. 4 online). Compared to urban women, the risk of receipt of an inappropriate agent among rural women was higher for OB-GYN providers (adjusted RR 1.09, 95% CI, 1.04–1.14), was similar for emergency medicine providers, and was lower for internal medicine (adjusted RR 0.93, 95% CI, 0.91–0.95) and family medicine and pediatric providers (adjusted RR 0.96, 95% CI, 0.95–0.97).

Table 3. Risk Ratio Estimates for the Association Between Rural–Urban Status and Receipt of an Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescription

Risk of receipt of inappropriate antibiotic duration

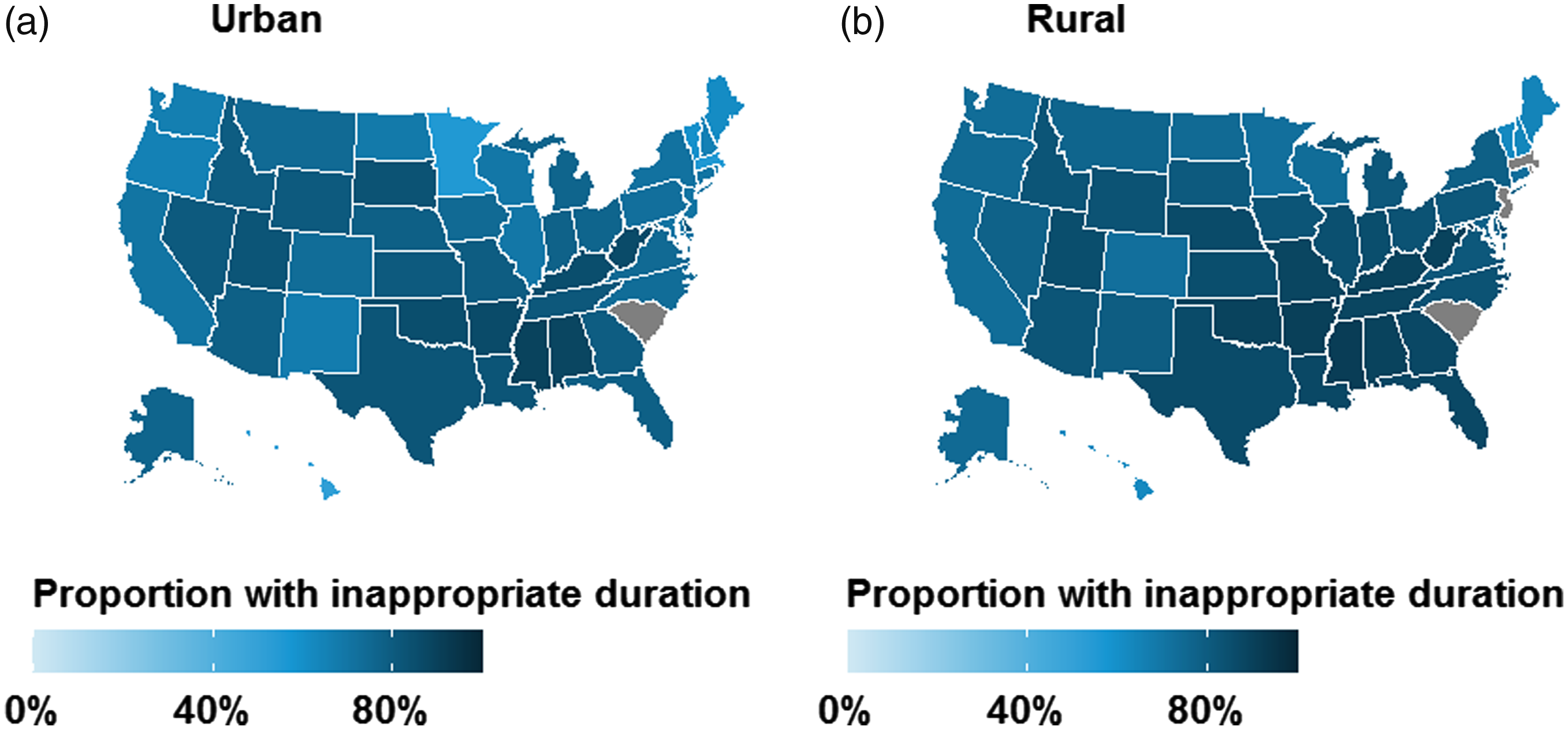

Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 6 (online) present the distribution of antibiotic prescriptions by duration, overall and by rural–urban status. Most prescriptions (76.1%) were written for inappropriate durations. Of 507,737 prescriptions with inappropriate duration, almost all were written for a duration that was longer (N = 501,496; 98.8%) than recommended, rather than shorter (N = 6,241; 1.2%). For all antibiotic agents combined, rural women were prescribed inappropriate antibiotic durations more frequently than urban women (83.9% vs 74.9%). Similarly, within analyses stratified by antibiotic agent, rural women received more prescriptions with inappropriate durations than urban women: nitrofurantoin (85.4% vs 80.7%), TMP-SMX (84.4% vs 70.4%), fluoroquinolones (87.1% vs 78.5%), and β-lactams (45.8% vs 37.4%).

Over the study period, the quarterly proportion of patients who received inappropriate durations declined from 78.3% in mid-2011 to 73.4% in mid-2015 (Fig. 2B). The use of inappropriate agents declined among urban women (from 77.1% to 72.0%) and less so among rural women (from 85.1% to 83.2%). State-level maps illustrate ubiquitous use of antibiotic prescriptions with inappropriate durations in all regions, particularly the South and Midwest (Fig. 4). Rural–urban differences in inappropriate duration use remained generally constant over time within subgroups of antibiotic agent, geographic region, and provider specialty (Supplementary Figs. 5–7 online).

Fig. 4. Geographic distribution of antibiotic prescriptions with inappropriate duration for treatment of uncomplicated UTI in the outpatient setting by rural–urban status: (A) urban and (B) rural. Results are unadjusted and are not presented for grey states due to business agreement with IBM.

In the multivariable model, rural women were 10% more likely to receive an antibiotic prescription for an inappropriate duration (adjusted RR 1.10, 95% CI, 1.10–1.10) compared to urban women (Table 3). Results were robust to additional adjustment for health insurance plan type. Results of subgroup analyses were consistent across geographic regions, provider specialties, and antibiotic agents (Supplementary Fig. 8 online).

Discussion

We conducted a cohort study using a large claims database to examine rural–urban differences in real-world antibiotic treatment patterns in a population of uncomplicated UTI patients with commercial insurance in the United States. Of 670,450 patients in our study, nearly half received inappropriate agents and almost three-quarters received prescriptions with inappropriately long treatment durations. We observed little rural–urban difference in the receipt of inappropriate agents in the overall population, but results varied across geographic regions, provider specialties, and calendar time. We observed rural–urban differences in receipt of antibiotic prescriptions for inappropriate durations, wherein rural women were more likely to receive inappropriately long durations. These differences in inappropriate duration were consistent across antibiotic agents, geographic regions, and provider specialties. Overall, we observed slight decline in inappropriate antibiotic use for UTI (both by agent and duration) over time.

Our observations of overall or subgroup variability in rural–urban differences in appropriate use of antibiotic agents and durations have several possible explanations. Regional variability in agent use may be related to local patterns of uropathogen resistance, especially for Escherichia coli, the predominant bacterial cause of UTIs.Reference Sannes, Kuskowski and Johnson21 However, we are not aware of regional uropathogen resistance data in the United States with which to compare with our findings. It is recommended that first-line TMP-SMX be avoided in settings with known local resistance; first-line nitrofurantoin is an appropriate alternative choice for therapy due to minimal resistance,Reference Gupta, Hooton and Naber8,Reference Sanchez, Babiker, Master, Luu, Mathur and Bordon10 though studies of antibiotic prescriptions for other indications and patient populations demonstrate that providers frequently prescribe non–first-line agents.Reference Bishop, Schulz, Kong, James and Buising22–Reference Steinman, Landefeld and Gonzales26

In addition, rural–urban differences in use of appropriate antibiotic durations may be related to patient- and provider-level factors. For example, distance to healthcare (a patient-level factor) is associated with lower adherence to treatment and poorer outcomes in oncology patients.Reference Ambroggi, Biasini, Del Giovane, Fornari and Cavanna27,Reference Campbell, Elliott, Sharp, Ritchie, Cassidy and Little28 In the context of our study on antibiotic prescribing, rural women were more likely to receive longer treatment durations, possibly in an effort to avoid treatment failure-related healthcare encounters that require travel. These rural–urban differences may also be associated with provider-level factors. Late-career physicians, which are more prevalent in rural locations,Reference Fordyce, Doescher and Skillman29 are more likely to prescribe antibiotics with longer durations.Reference Fernandez-Lazaro, Brown, Langford, Daneman, Garber and Schwartz30

Our study has several potential limitations. First, our guideline-based definition of inappropriate duration may be too lenient given recent meta-analytic evidence that shorter-course regimens of some agents have similar effects on clinical responseReference Kim, Kim and Lee31; however, the impact of possible misclassification on the results would be minimal because the proportion of prescriptions with inappropriate durations were overwhelmingly longer (98.8%) rather than shorter (1.2%) than recommended. Second, the study population is limited to commercially insured women from a database that oversamples residents of the South and undersamples residents of the West. Thus the results may not be generalizable to other populations such as Medicaid-insured or uninsured women, and they may not be directly generalizable to the commercially insured population in the United States. Third, our definition of rural–urban status was based on zip-code–level data rather than distance to urbanized areas and clusters or access to healthcare.18 Individuals classified as rural residents in our study reside in a wide variety of settlements, from densely settled small towns and exurbs on the fringes of urban areas, to more sparsely populated and remote areas.Reference Hall, Kaufman and Ricketts13 Fourth, the database lacked information on race or ethnicity or income level; thus, we were not able to account for these important disparity-related variables in the analysis, which may result in confounding bias. Lastly, test results from urine cultures were not available in the database; therefore, we were not able to account for prescribing decisions influenced by susceptibility results. However, we expect the impact of test results on prescribing practices to be minimal because guidelines recommend empiric treatment of uncomplicated UTI.

Despite these limitations, our study identified rural–urban differences in antibiotic prescribing, including an actionable disparity in the duration of antibiotics that disproportionately affects women who live in rural locations. In recent years, little effective progress has been achieved to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for uncomplicated UTI. Given the large quantity of inappropriate prescriptions annually in the United States, as well as the negative patient- and society-level consequences of unnecessary exposure to antibiotics, antimicrobial stewardship interventions are needed to improve outpatient UTI antibiotic prescribing, particularly in rural settings. Existing recommendations for the promotion of outpatient antibiotic stewardship include establishing personal and policy commitment to change, reporting progress, and enhancing education around best practices.Reference Sanchez, Fleming-Dutra, Roberts and Hicks32 Future research is needed to effectively identify, disseminate, and implement guideline-concordant antibiotic prescribing in rural settings.

Financial support

This work was supported by a grant from the NCATS (NIH grant no. KL2 TR002346 to A.M.B. and M.J.D). Data programming for this study was conducted by the Center for Administrative Data Research, which is supported in part by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences (grant no. UL1 TR002345) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the NIH (grant no. R24 HS19455) through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Conflicts of interest

M.A.O. reported receiving investigator-initiated research funds from Sanofi Pasteur, Pfizer, and Merck and serving as a consultant for Pfizer.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2021.21