To the Editor—The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that in 2018, emergency departments (EDs) generated 12.7 million antibiotic prescriptions. 1 Up to 50% of these prescriptions may have been inappropriate with respect to antibiotic use or selection, dosing, and duration, based on outpatient prescribing estimates. 2 Improving prescribing is imperative, but historically, EDs are underrepresented in antibiotic stewardship studies. Reference Pulia, Redwood and May4 EDs may benefit from implementation of the recommended components of an antimicrobial stewardship program, including decision-making tools based on facility-specific practice guidelines. Reference Barlam, Cosgrove and Abbo3 For example, antibiotic order sets within an electronic medical record (EMR) have been shown to improve adherence to evidence-based prescribing for single diagnoses, Reference Heckler, Fox and Son5,Reference Forest, van Schooneveld and Kullar6 although the use of multiple order sets for a variety of diagnoses has not been well studied. We implemented EMR order sets for common infectious diagnoses in the ED, compared the prescribing practices of providers who utilized them to those who did not, and surveyed providers for barriers to use.

Methods

This study was part of a larger intervention to improve antibiotic prescribing and reduce Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) at a 500-bed quaternary-care academic medical center with ∼50,500 yearly ED visits. Order sets were created for cystitis, pyelonephritis, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and cellulitis that included recommended antibiotics and first dose in the ED, followed by a prepopulated prescription for an appropriate duration. Antibiotic choices were prioritized based on clinical practice guidelines, Reference Gupta, Hooton and Naber7–9 the hospital antibiogram, and a desire to avoid antibiotics associated with higher CDI risk (eg, fluoroquinolones), with guidance included for dosing in patients with renal impairment.

The order sets were deployed in March 2019, with clinician education via a presentation (40% attendance), 1-on-1 sessions (60% of clinicians), and 3 informational e-mails. A survey adapted from Vandenberg et al Reference Vandenberg, Vaughan and Stevens10 was sent to all ED clinicians in November 2019 to assess whether the order sets were being used and whether they were beneficial to their practice.

Additionally, a retrospective chart review was conducted from October 1, 2019, to November 1, 2019, to assess the impact on prescribing practices for patients presenting with 1 of the 5 diagnoses with a corresponding order set, identified using International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes. Charts were manually reviewed for whether an order set was used, antibiotic doses given in the ED, antibiotic prescribed, creatinine clearance, special population status (eg, pregnancy or organ transplant), prior culture data, and whether a subspecialty consultation was obtained. Patients were excluded from the analysis if antibiotics were not prescribed, if they belonged to a special population, or if they received subspecialty consultation. In total, 213 charts were reviewed and 104 met inclusion criteria. Encounters with order-set use were compared to those without order-set use for appropriate antibiotic selection, duration, and renal dosing. We used the χ2 test with a P < .05 significance level and OpenEpi Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health version 3.01 software (www.openepi.com). Patients who received an inappropriate antibiotic were excluded when comparing durations of therapy, and those without a measured creatinine level were excluded when comparing appropriate renal dosing. The study was approved by the Emory Institutional Review Board.

Results

Provider survey

The overall response rate was 59%. Just more than half (51.6%) of clinicians were physicians and 48.4% were APPs. Most respondents were aware of the order sets (75.0%) and 59.4% reported using them. Of the clinicians who used the order sets, 78.9% reported that they saved time, 84.2% reported ease of use, and 94.7% reported successful use.

Chart review

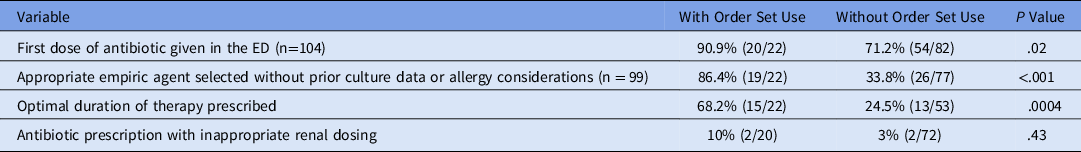

Order sets were used in 22 (21%) of 104 qualifying patient encounters. Use varied by diagnosis. An order set was used in 12 (43.8%) of 32 patients with uncomplicated cystitis, 2 (22.2%) of 9 patients with pyelonephritis, 2 (20%) of 10 patients with cellulitis, 3 (6.7%) of 45 patients with complicated cystitis, and none of 8 patients with pneumonia or COPD. Patients were more likely to receive the first antibiotic dose in the ED when order sets were used (P = .02) (Table 1). Patients were also more likely to receive an appropriate antibiotic (P < .001) and to have an appropriate duration prescribed (P = .0004) when order sets were used. We did not detect a statistically significant difference in appropriate renal dosing between the 2 groups.

Table 1. Appropriate Antibiotic Prescribing With and Without Order Set Use

Note. ED, emergency department.

Discussion

In this study, EMR antibiotic order sets for treatment of common infectious syndromes were implemented in the ED. They were only used in 21% of qualifying patients, but in these cases they were associated with improved antibiotic selection, first-dose timing, and prescription duration. Almost all providers who reported utilizing the order sets noted that they were easy to use and saved time.

Given the advantages of order-set use, improving uptake will be a focus of future interventions. Historically, order sets have been evaluated for single conditions, Reference Heckler, Fox and Son5 but availability of multiple order sets may improve provider acceptance. We observed that clinicians used order sets for uncomplicated cystitis more frequently than for other conditions, which may be related to the frequency of diagnosis and a large number of antibiotic choices. Ensuring that providers who used the cystitis order set are aware of the other options and can educate other clinicians may help to increase acceptance.

Larger studies are needed to further evaluate the impact of order sets on prescribing and patient care outcomes because early data indicate that they may improve antimicrobial stewardship. In the future, we plan (1) to expand order-set offerings within the ED and in outpatient settings; (2) to increase use via additional didactics, peer-to-peer education, audit and feedback; and (3) to evaluate trends in antibiotic prescribing over a longer time period.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Ashley Jones, PharmD, BCIDP, for assistance related to this study.

Financial support

This study was supported by funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Investments to Combat Antibiotic Resistance (grant no. 200-2016-91944).

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this study.