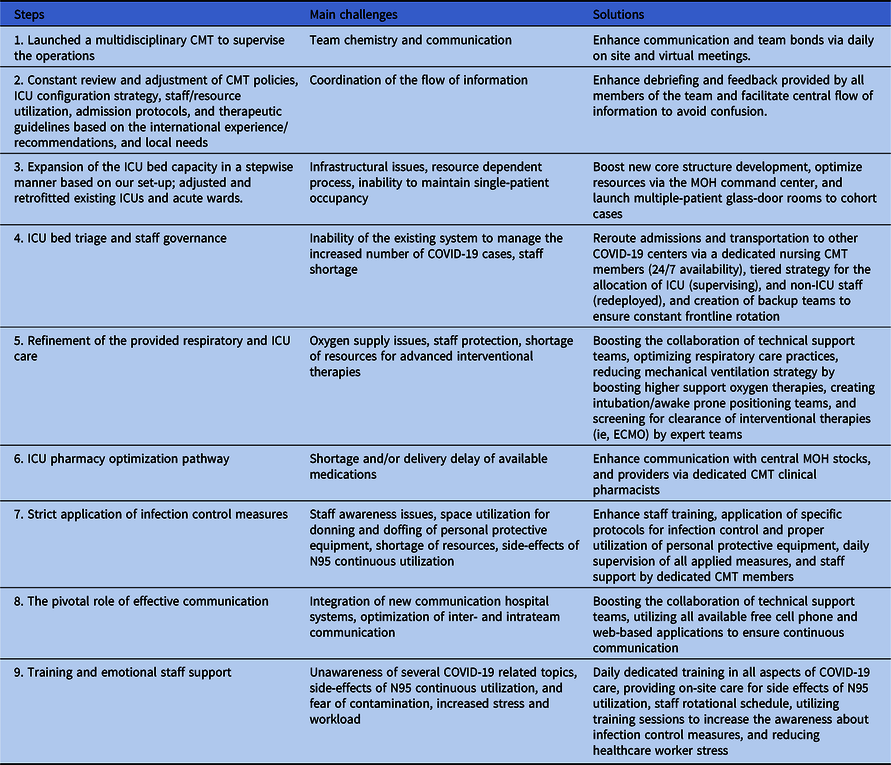

To the Editor—The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 disease (COVID-19) emerged in China and has spread throughout the world.Reference Guan, Ni and Hu1 The first case of COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia was confirmed on March 2, 2020, and presently almost 200,000 people have been infected here.2 The Ministry of Health (MOH) has responded to the COVID-19 outbreak by designing clusters of governmental hospitals to accommodate the increased flow of patients. Although our bed-occupancy rates never exceeded 80% until 2019, the situation has changed dramatically since March 2020, when the intensive care unit (ICU) occupancy rates reached 100% due to the pandemic. Hence, our hospital has been under pressure to upgrade our ICU services. We have used crisis management tactics in configuring our medical city (Table 1). First, we created a multidisciplinary crisis management team (CMT) to supervise the operations, and we promptly applied a surge plan based on the available scientific evidence. Our CMT policies, ICU configuration strategy, staff and resource utilization, admission protocols, and therapeutic guidelines have been reviewed continually based on new international updates, emerging therapies, and the recommendations of our national health authorities.2–Reference Li, Gong and Yan5 By adjusting, and retrofitting existing ICUs, and acute wards. we have expanded the ICU bed capacity in a step-wise manner: phase 1, 180 beds; phase 2, 240 beds; phase 3, 300 beds). Our main challenge has been to install new structures (ie, gas access, power circuits, monitors, and HEPA purifiers) in the pop-up units. We could not maintain single-patient occupancy; thus, we isolated cohorts of COVID-19 patients in multiple-occupancy glass rooms. Nursing stations have been set up outside these rooms; new circuits have been installed for the transmission of data and alarms; and new procedure carts have been arranged for each new unit. The ICU-bed triage and staff governance have been controlled by the CMT. Our CMT members have provided coverage 24 hours per day, 7 days per week to arrange the ICU admission flow and the transfer of patients to other hospitals based on the daily MOH plan. We have followed a tiered strategy in which we allocate experienced intensivists and nurses to supervise redeployed noncritical care physicians and nurses, and we also established back-up teams. The refinement of the respiratory and ICU care included changing the ventilator circuits and filters based on patient needs, avoiding nebulizers, creating specialized intubation and prone-positioning ventilation teams, and upgrading the oxygen supply system. The latter has been a major problem for our oxygen supply management team. Hence, we have promoted awake prone positioning and more oxygen-support therapies (ie, high-flow nasal cannula, and helmet continuous positive pressure ventilation) to avoid mechanical ventilation if possible. Interventional therapies (ie, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and therapeutic plasma exchange) have been carefully screened by expert teams to optimize resource utilization. The ICU pharmacy operations have been linked to the MOH central stock and supervised by pharmacists of the CMT to facilitate the prompt delivery of medications. Infection control measures have been strictly implemented in all hospital areas by creating specific zones and protocols for donning and doffing personal protective equipment, providing sanitizer dispensers, applying strict room-disinfection protocols, and providing safe waste handling.Reference Cheng, Wong and Chen6 Moreover, we have utilized novel transportation capsule isolation technology to minimize the risk of SARS-CoV-2 acquisition during inter- and intrahospital transportation.Reference Almuabbadi, Mhawish and Marasigan7

Table 1. Crisis Management Tactics in Configuring a Hospital by Upgrading its Intensive Care Unit Services in the COVID-19 Era

Note. CMT, crisis management team; MOH, Ministry of Health; ICU, intensive care unit; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

New hospital communication systems have been installed in the pop-up ICUs. The communication between frontline staff and the CMT is continuous. Because visitors were not allowed, family meetings were organized via web-based applications to reduce patient and family stress. Training and emotional staff support have been provided on a daily basis. We have utilized daily COVID-19 training sessions to provide additional emotional reassurance (ie, dual training and emotional support strategy). Moreover, ~600 COVID-19 patients have been hospitalized in our ICU over the past 4 months. Our staff’s nosocomial infection rate was ~3% during the early stages of the pandemic, and it has decreased to 0.5% since May 2020. As the current wave of COVID-19 subsides, we are focusing on maintaining our costly infrastructure upgrades. These could ensure that a proper set-up would be available to meet future needs.Reference Griffin, Karas, Ivascu and Lief3–Reference Li, Gong and Yan5 Stores of equipment, medications, and technical gadgets remains under CMT supervision. Continuous medical education of our staff about COVID-19 by our MOH could facilitate the management of future outbreaks. Regardless of the limitations in any healthcare system, hospitals should be prepared for future pandemics.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all healthcare workers for their hard work and sacrifice in the fight against COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.