Nearly 70 years ago, the American Psychological Association (APA) published its first Code of Ethics (“the code”) with two goals: (a) to provide general guidance to psychologists in the form of ethical principles, and (b) to present a set of standards that describe enforceable expectations for professional behavior (APA, 1953). Since that time, the field of psychology has grown and changed considerably, and the APA has revised the code on numerous occasions to maintain its relevance. Most recently, in 2021 the APA Ethics Code Task Force (ECTF) began revising the code again with the aim of “creating a Code that is transformational” while remaining “a leading practical resource regarding ethics for psychological science, education and practice”. Thus, it is currently an apt time to investigate the relevance of the code, both to psychology in general and to specific disciplines of psychology.

APA is a large and diverse organization, representing over 100,000 members and 54 divisions (APA, 2020). APA comprises subdisciplines such as clinical psychology and topical interest groups often representing specific work domains (e.g., Div. 39/Society for Psychoanalysis and Psychoanalytic Psychology; Div. 18/Psychologists in Public Service). The single code requires compliance from APA members of all those divisions, student affiliates, licensed psychologists, as well as members of those divisions and other organizations that have adopted the code even if they are not members of APA.

Since at least the 1980s when the Association for Psychological Science split with APA, clinically oriented psychologists have dominated the membership statistics of APA. The APA’s most recent membership statistics from 2019 also show that the three largest divisions by membership are Div. 40 (Clinical Neuropsychology), Div. 12 (Clinical Psychology), and Div. 42 (Psychologists in Independent Practice)—all divisions comprising mental health researchers and practitioners. It is thus not surprising that the code mostly envisions psychologists as engaged in psychotherapeutic research and/or practice with individuals, despite nonclinicians also being involved in its initial development—for example, two former SIOP presidents (Bray and Seashore) served on the ethics committee that shaped the early formation of the code.Footnote 1

However, over the years psychologists from a diverse range of nonclinically oriented APA divisions—who represent a growing proportion of APA’s membership (APA, 2020)—have argued that the code should better represent the ethical situations faced by psychologists operating outside the bounds of healthcare. For example, critiques of the Code’s relevance can be heard from industrial-organizational (Lowman, Reference Lowman1993), teaching (Keith-Spiegel, Reference Keith-Spiegel1994), forensic (Lees-Haley et al., Reference Lees-Haley, Courtney and Dinkins2005), quantitative (Wasserman, Reference Wasserman2013), consulting (Gebhardt, Reference Gebhardt2016), community (Campbell & Morris, Reference Campbell and Morris2017), and school psychologists (Firmin et al., Reference Firmin, DeWitt, Smith, Ellis and Tiffan2018). Some divisions and practice areas (e.g., National Association of School Psychologists) have even supplemented the APA’s Code by developing their own ethics codes. To date, researchers have not systematically examined the code’s applicability to actual ethical incidents in nonclinical domains of psychology, rendering the code’s applicability to those areas unknown.

This paper presents just such an empirical investigation of the most recent version of the code (APA, 2017) with respect to ethical incidents from industrial and organizational (I-O) psychology (APA Div. 14) as an exemplar. This investigation offers several potential contributions for the field. First, the resulting recommendations may immediately inform upcoming revision efforts and serve as a model for systematically improving the usefulness of the code for I-O psychologists as well as psychology more broadly over time. Second, our findings may aid in training aspiring I-Os to better navigate ethical dilemmas, thus advancing the pedagogy of I-O psychology. Third, our findings may advance both the practice and science of I-O psychology, both of which often involve working in close partnership with organizations and employees. Thus, despite their different career paths, practitioners and academics alike may similarly require guidance from the code to navigate the same types of ethical dilemmas (Watts & Nandi, Reference Watts and Nandi2021). Last, and more broadly, we believe that our methodology will generalize to other APA divisions who may be interested in investigating the issue. The following research questions guided our investigation:

RQ1: How applicable is the code to ethical situations reported by I-O psychologists?

RQ2: What are the potential deficiencies in the code (i.e., substantive gaps or ambiguities), if any, and how might the code be improved to address those deficiencies?

Historical development of the code

There have been roughly a dozen revisions to the original 1953 Ethics Code, starting just 6 years after its publication (APA, 1959)—some revisions being major overhauls (in 1977, 1981, and most recently in 1992 and 2002), and some limited to editing portions of the code or adding sections. According to the APA Ethics Committee (1997), “An interim revision will be undertaken if the Ethics Committee, Board of Directors, or Council of Representatives determines 1) that there is an urgent concern about the Ethics Code that should not be delayed until the major revision and 2) that there should be an interim revision” (p. 898). Indeed, such interim revisions were made most recently in 2009 (effective June 1, 2010), clarifying that Standard 1.02 (Conflicts Between Ethics and Law) and Standard 1.03 (Conflicts Between Ethics and Organizational Demands) provide no defense to torture; and in 2016 (effective January 1, 2017), similarly amending Standard 3.04 (Avoiding Harm) to prohibit participation, facilitation, assisting, or otherwise engaging in torture.

From the beginning, the APA worked to incorporate members’ initial input or feedback to draft documents (cf., Golann, Reference Golann1970; Joyce & Rankin, Reference Joyce and Rankin2010; Pope & Vetter, Reference Pope and Vetter1992, for summaries). The initial code was the first to be based on actual “critical incidents” solicited from those to whom it would pertain, based on more than 2,000 contributions (APA, 1953, Preamble). The major 2002 revision received over 1,300 comments (APA, 2002), and the limited 2009 and 2016 revisions received 81 and approximately 275 comments, respectively (APA Ethics Committee, 2009; APA, 2016). But, as lamented by Pope and Vetter (1992), since 1953—aside from a focused survey in 1982 concerning research with human participants— “APA never again conducted a mail survey of a representative sample of the membership as the basis for revising the general Code” (p. 398). The present effort revives elements of this earlier critical incident technique to examine the code’s relevance to I-O psychology.

Applicability of the code to I-O psychology

The Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP/APA Div. 14) is one of the APA’s 54 divisions. The nature of professional practice in I-O psychology entails working with various types of clients, executives, team members, business consultants, human resource managers, and other organizational representatives or stakeholders in a wide range of activities, in individual, team, and organization-level contexts. Currently, only 19 of the 89 standards (21.3%) make an explicit reference to psychologists working in, with, or for organizations in some capacity.

More than 15 years ago it became apparent at a panel symposium conducted at an annual SIOP conference that some I-O psychologists believed the code was inadequate for I-O psychology and that the field needed its own version; others held the opposite opinion (Lefkowitz et al., Reference Lefkowitz, Greenberg, Jeanneret, Knapp, McIntyre, Lowman and Behnke2006). (SIOP long ago adopted the APA Ethics Code as its own.) In subsequently informing the APA membership about that discussion, the APA’s ethics officer, who had been one of the participants, reframed the issue as having to do with articulating the gap between the abstract ethical principles and day-to-day practices reflected in the standards. “We can narrow the gap by writing more elaborate and specific ethical standards, which will provide more guidance but leave less room for our professional judgment and discussion” (Behnke, Reference Behnke2006, p. 66). In fact, for many years the code’s revision process has consistently aimed:

toward keeping the Ethics Code standards, to the extent possible, as simple statements, behaviorally focused, and expressed as unitary concepts, in order to facilitate their application. To have done otherwise could have resulted in a Code of such length and complexity as to diminish its usefulness.” (Canter et al. Reference Canter, Bennett, Jones and Nagy1994, p. xi)

Behnke (Reference Behnke2006) also acknowledged: “Drawn largely from the biomedical ethics literature, the principles may not adequately speak to I-O psychology and so may need to be re-examined in the next Ethics Code revision.” Complicating matters further, other applied psychologists have more recently voiced the opinion:

that the revisions of the APA ethical standards [should] give serious consideration to the elimination of all statements regarding specialty areas of practice…. We strongly suggest that the next revision of the standards only include those that are applicable to everyone who belongs to APA.” (Society of Consulting Psychology, 2021)

However, an important takeaway from this discussion is that none of the opinions—pro, con, or otherwise—have been shaped by the consideration of systematically evaluated empirical data.

Determining applicability

Issues of interpretation

Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Vasquez, Behnke and Kinscherff2010) observed that “the Ethics Code has 89 ethical standards, all of which have potential applications in a variety of complex and nuanced situations and settings” (p. 7). It is not surprising therefore, that various knowledgeable authorities have felt the need to publish substantial explanatory commentaries on the code (Bersoff, Reference Bersoff2008; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Vasquez, Behnke and Kinscherff2010; Canter et al., Reference Canter, Bennett, Jones and Nagy1994; Fisher, Reference Fisher2017). The situation is especially noteworthy when one realizes that—despite the involvement of nonclinicians in its initial development—both the code and the commentaries were written largely from the unitary perspective of clinical psychology and psychotherapy. How much more challenging must the requisite interpretive inferences be to apply the code usefully to other specialty areas?

This challenge is recognized by the current ECTF, who realize that it is important to achieve “a broader breadth and application of the code across disciplines” and to establish a “Code that addresses the complexities of interactions between psychologists and their clients, including clients that are organizations, companies, etc.” (APA, 2021, emphasis added). We anticipate that doing so will not be easy. In sum, the applicability of the principles and standards of the code to situations comprising particular domains of interest (professional specialties; problem areas; work settings) is a function first, perhaps foremost, of their interpretability in each context. And in our experience, the principles and standards seem clearer when simply reading them than when trying to apply them to actual situations, such as those represented by the incidents investigated here. Moreover, one can anticipate that the written incident descriptions are probably more limited in content and complexity than the actual ethical situations they represent, which likely include a multitude of additional real-life details. Therefore, in order to conduct a reasonably meaningful and fair assessment of the code’s real-life applicability, we considered it is necessary and appropriate to employ what might be described as expansive or “lenient” standards of interpretation, as described next.Footnote 2

Who is the ethics violator?

A vast majority of the 94 principles and standards are written as guides or admonishments to psychologists, assuming that they are the potential miscreant: (“Psychologists strive to…”; “Psychologists establish…”; “Psychologists cooperate…”; “Psychologists refrain from…”; “Psychologists take reasonable steps to…”; “Psychologists do not…”; “Psychologists provide…”; etc.). That is, of course, in keeping with the fact that psychologists are the focal audience of the code’s educative and enforcement functions. However, as noted earlier, many practicing I-O psychologists work closely with clients, colleagues, and other stakeholders who have failed to “avoid harming others,” disregarded a “conflict of interest,” or engaged in inappropriate “multiple relationships” or “exploitative relationships.”

Thus, when reviewing ethical incidents, we considered an element of the code as applicable if its substance reflected an ethical issue presented in the incident, irrespective of who was the violator. In other words, if the reported incident concerns an action taken, contemplated, or intended that is proscribed in the code (or something prescribed in the code is not done), the code was deemed “applicable” even if the actor was not our respondent or not even a psychologist.Footnote 3 This decision rule was necessary to accommodate the complex, diverse, and interdependent nature of ethical situations encountered by I-O psychologists—once one becomes aware of an ethical situation, it becomes one’s professional duty to report or otherwise address it (as prescribed in Standards 1.04 and 1.05), regardless of whether the alleged perpetrator is a psychologist. Additionally, this approach was corroborated by the finding that more than 40% of the alleged or potentially unethical persons in the situations reported were not, in fact, psychologists (an issue we return to when discussing ambiguities in the code).

Focusing on the intent of the standards

In some cases, a literal reading of a standard would provide an overly narrow and misleading conclusion regarding applicability. In those instances, it seemed reasonable and appropriate to focus on the apparent purpose of the standard. For example: (a) Standard 1.01 (Misuse of Psychologists’ Work) was considered applicable even when it was someone else’s work being misused; (b) Standard 1.04 (Informal Resolution of Ethical Violations) was considered to provide appropriate advice even if the possible ethical violation was by another who was not a psychologist; (c) a standard such as 3.02 (Sexual Harassment) was considered applicable even when our survey respondent was the victim of harassment. It seems to us that “stretching” the interpretation of the code in this manner is not merely permissible but is requisite to a fair investigation of our research questions—and is in keeping with the intent of the code to provide flexibility to psychologists.

Accommodating the specialty area

Similarly, there are ethical issues associated with aspects of professional practice in I-O psychology that are not reflected in the code but that can readily be accepted as analogous to matters that are enumerated. For example: (a) Standard 1.05 (Reporting Ethical Violations) may in some instances entail reporting to a corporate board or academic committee, as opposed to a body within professional psychology; (b) Standards 7.06 and 7.07, concerning assessment of, and sexual relationships with, students and supervisees, although framed in the educational context, was interpreted as referring equally to organizations and subordinate employees; and (c) although executive coaches do not conduct psychotherapy and generally are not trained to do so, there are enough similarities to warrant considering some standards in category 10 (Therapy) as potentially applicable to coaching (e.g., informed consent; sexual intimacies; interruptions and termination of the psychologist–client relationship).

We believe that these expansive interpretive guidelines are commensurate with the spirit and intent of the code. As noted in the code’s Preamble, “Most of the ethical standards are written broadly, in order to apply to psychologists in varied roles, although the application of an ethical standard may vary depending on the context” (p. 2). Indeed, a consideration of the code’s applicability to I-O psychology (and to other specialty areas) would be a meaningless enterprise otherwise. With these interpretational parameters in mind, we now turn to describing the methodology used to investigate the relevance of the code to I-O psychology.

Method

Sample

The sample consisted of 398 narrative descriptions of ethical incidents drawn from a publicly available dataset of anonymous qualitative responses provided by associates, members, and fellows of SIOP when participating in SIOP-sponsored ethics surveys conducted in 2009 and 2019 (Lefkowitz, Reference Lefkowitz2021; Lefkowitz & Watts, Reference Lefkowitz and Watts2022).Footnote 4 These incidents were provided by 339 I-O psychologists who indicated that they were “directly involved” in the reported situation in some capacity. Some respondents contributed up to two narrative incidents. Because the 2009 and 2019 samples were similar in terms of demographics and results, we treat them here as a single (i.e., combined) sample.Footnote 5

The sample of 339 I-O psychologists consisted of approximately equal numbers of male (50.2%) and female (46.9%) respondents (.3% other and 2.7% unreported). Most respondents (91.2%) held doctoral degrees, and the majority (79.9%) reported their highest degree being earned in the field of I-O psychology, followed by some other psychology specialization (10.0%) or business (6.8%). Most respondents (79.9%) were SIOP Members, followed by Fellows (10.6%), and Associates (4.1%). The number of years passed since obtaining one’s highest degree, or the “career stage,” of respondents was diverse, with roughly 34.8% in early career (0 to 10 years), 26.3% in mid career (11 to 20 years), and 36.9% in late career (>20 years). Drawing on demographic data from the 2019 ethics survey (Lefkowitz & Watts, Reference Lefkowitz and Watts2022), we learned that most of the respondents (86.8%) who provided ethical incidents were based in the United States, with the remaining incidents (13.2%) coming from international respondents. Additionally, the ethical incidents were distributed across all major work areas of I-O psychology, with 31.6% of incidents coming from academe, 29.6% from internal practitioners, and 38.8% from external practitioners. These demographics are largely representative of SIOP’s overall membership statistics (SIOP, 2020), with the exception that Associates (i.e., professionals holding a master’s degree) were underrepresented, whereas Fellows were slightly overrepresented.

Survey respondents were asked to “describe an ethical situation with which you are personally and directly familiar that occurred within the past few years (i.e., recently enough for you to remember the details).” The median incident length was 130 words (mean = 163.82, SD = 132.74).

Coding procedures

A thematic content analysis approach was used to explore the applicability of the principles and standards of the code to ethical incidents reported by I-O psychologists (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Four subject matter experts trained to serve as judges, or coders, of the incidents. These judges included one professor emeritus, one assistant professor, one postdoctoral researcher, and one doctoral research assistant in I-O psychology. Two of the judges have served as members of SIOP’s Committee for the Advancement of Professional Ethics. Coding took approximately 3 months, and the procedures were as follows. First, the two senior judges reviewed the principles and standards presented in the code and coded an initial sample of 15 incidents. Through coding and discussing these initial incidents, the senior judges established consensus around the judgment of each variable and generated an initial coding protocol with guidance for all of the judges.

Second, all four judges engaged in a 2-hour training session in which they reviewed the code and coding protocol, and practiced coding three incidents together. Whenever disagreements or ambiguities emerged around how to apply a particular principle or standard to an incident (see “Issues of Interpretation” section presented earlier), the four judges discussed these issues until a consensus was reached, and the coding protocol was updated accordingly.

Third, the remaining incidents were randomly assigned to judges to code independently. Each of the remaining incidents were coded independently by two judges, and individual judges were paired with one another an approximately equal number of times across the incidents so that no single pair of judges had a disproportionate influence on the results. The judges discussed ambiguous incidents or coding issues with one another periodically throughout the project and updated the coding protocol accordingly. Interrater agreement statistics were monitored throughout the coding process. Any principle or standard falling below an absolute agreement of 70% was discussed throughout the process to facilitate convergence. The only two variables with agreement statistics falling below the 70% threshold were the principles of Fidelity and Responsibility (69.4%) and Integrity (65.7%).

Applicability variables

The principles and standards of the APA Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (2017) served as our main variables. For each of the five principles and 89 standards presented in the code, judges coded a “1” to indicate that the principle/standard was applicable to the incident or a “0” to indicate the principle/standard was not applicable.

Judges coded three additional variables to provide more information about the contents of each incident. These variables, and their rationale, included: (a) “Was the alleged perpetrator, or potential perpetrator, a psychologist?” (The Code is “intended to provide guidance for psychologists…that can be applied by the APA and other bodies [such as SIOP] that choose to adopt them” APA, p. 2.); (b) “Did the protagonist attempt to informally resolve the issue with the perpetrator?” (prescribed in Standard 1.04); and (c) “Did the protagonist formally report the situation to a higher institutional authority?” (conditionally prescribed in Standard 1.05). These three variables were coded as “1” to indicate yes, “0” to indicate no, or “9” to indicate unclear.

Given the categorical nature of the coding, it was necessary to resolve any disagreements among judges prior to analysis. A default rule was applied to resolve disagreements, such that if any judge marked a variable as applicable for a particular incident it was considered applicable. Although this decision rule may be expected to slightly inflate the observed applicability of some principles and standards (particularly those few variables where interrater agreement statistics were lower), it was used in the spirit of giving the code the “benefit of the doubt” (as we did with the “lenient” decision rules for judging applicability, as described earlier). Thus, our results may be interpreted as an upper bound estimate of the applicability of the principles/standards to the cases reported by I-O psychologists.

Agreement statistics were monitored throughout the coding process by calculating the average observed agreement across all pairs of judges, which can range from 0% to 100%.Footnote 6 For the five principles, the average agreement ranged from 65.7% to 82.3% (Mdn = 76.6%, M = 75.1%, SD = 7.3%). For the 89 standards, the average agreement ranged from 71.2% to 100.0% (Mdn = 97.7%, M = 94.9%, SD = 6.8%). Finally, the agreement statistics for the three additional variables were also acceptable at 76.7%, 80.7%, and 88.7%, respectively.Footnote 7

Deficiency variables

Two qualitative variables were also coded to record judges’ impressions of any substantive deficiencies in the code as well as any further notes about how an incident was interpreted. Judges indicated that a deficiency was substantive whenever they perceived that the code did not provide adequate guidance for addressing a particular ethical incident, either due to ambiguities or the absence of necessary information (i.e., gaps) in the code. Thus, the qualitative variables asked: (1) “Are there any substantive gaps or ambiguities in the code?” and (2) “Other notes about the incident?”

Judges generated a total of 371 comments in response to these two qualitative variables. These comments were reviewed to identify themes that might reflect substantive deficiencies encountered when applying the code to ethical incidents reported by I-O psychologists. First, the four judges independently reviewed all 371 comments and flagged any comments they perceived to represent substantive gaps or ambiguities. Among these comments, 216 (59.2%) were flagged as potentially substantive by at least one judge, and 155 (41.8%) were not flagged. The majority of comments that were not flagged came from judges’ “other notes about the incident,” such as indicating that aspects of an incident were vague or otherwise difficult to code. The 216 comments that were flagged as indicating potentially substantive deficiencies were associated with 170 of the 398 incidents. Thus, approximately 42.7% of the incidents generated at least one comment from judges indicating a substantive deficiency or ambiguity in the code.

Next, we sorted those 216 comments based on how many judges flagged them, starting with those flagged by all four judges. Among the 216 comments, 33 (15.3%) were flagged by all four judges, 46 (21.3%) were flagged by three judges, 71 (32.9%) were flagged by two judges, and 66 (30.6%) were flagged by one judge. One of the senior judges then reviewed each comment and generated themes reflecting the core content of each comment. For example, the theme “Working with Non-Psychologists” was generated when encountering the following comment: “Psychologists avoid working with other professionals or firms who display a pattern of unethical behavior.” No limit was placed on the number of possible themes that could be generated, and some comments represented more than one content theme.

Once all 216 comments were associated with at least one content theme, the same judge reviewed the list of themes and revised them as needed. Some themes were combined, whereas others were divided into multiple themes to ensure the themes reflected an appropriate level of specificity for the data (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). That is, special attention was paid to maximizing both the internal homogeneity and the discriminability of themes (Patton, Reference Patton1990). Finally, all four judges reviewed the revised set of content themes and how they were applied to each comment. Following a series of discussions, the judges reached a consensus on the final structure and labels for the themes reflecting apparent deficiencies in the code, along with recommendations for resolving them.

Results

Results are presented in two sets. First, we present the applicability statistics for the five ethics principles, 89 standards, and three additional variables. Then, we present the qualitative content themes extracted from judges’ comments about substantive deficiencies or ambiguities in the code.

Applicability statistics

The following applicability statistics capture the frequency with which a particular principle or standard—as defined in the code—was judged as applicable to incidents in our sample. When interpreting these statistics, a caveat should be borne in mind. More (or less) frequently applicable principles or standards are not necessarily more (or less) important. Applicability statistics simply indicate which principles and standards are more (or less) prevalent. These statistics provide no information about the severity of incidents (some standards may be violated rarely but are nevertheless quite serious). For example, just because incidents involving fabrication of data tend to be reported rarely, this does not suggest that standards prohibiting fabrication are less important or that they should be omitted from future versions of the code. These statistics provide a starting place for understanding which principles and standards tend to be most frequently applicable for I-O psychology, and they should be interpreted in the context of the qualitative themes reported later.

Principles

The code’s five general principles all were applicable in varying degrees to the narrative incidents reported by I-O psychologists. On average, 2.81 principles were coded as applicable to each incident, and each principle was, on average, applicable to 56.1% (Mdn = 50.5%) of the incidents. The most frequently coded principles were Fidelity and Responsibility (87.4%) and Integrity (77.6%), and the least frequently coded was Justice (24.1%). Table 1 presents the rank-order applicability statistics for all five principles.

Table 1. Rank-ordered principles and categories of standards based on applicability

Standards

Among the 89 standards presented in the code, 75 (84.3%) were applicable to at least one incident, whereas 14 (15.7%) standards were never coded as applicable. On average, 7.53 standards were coded as applicable to each incident, and each standard was, on average, applicable to 8.5% (Mdn = 3.0%) of the incidents, indicating the complexity of mundane ethical issues. Of the 10 categories of standards, the most applicable on average were those related to Resolving Ethical Issues (30.7%), Human Relations (16.7%), Privacy and Confidentiality (11.8%), and Assessment (8.1%). In contrast, standards within the category of Therapy (0.0%) were, except for one incident, not applicable. Table 1 presents the average rank-order applicability statistics for the 10 categories of standards.

Of the 89 individual standards, the 10 most applicable were Informal resolution of ethical violations (81.9%), Conflicts between ethics and organizational demands (61.8%), Reporting ethical violations (49.0%), Avoiding harm (43.5%), Cooperation with other professionals (38.8%), Maintaining confidentiality (26.6%), Conflict of interest (26.4%), Misuse of psychologists’ work (24.9%), Psychological services delivered to or through organizations (24.6%), and Exploitative relationships (24.4%). In contrast, 29 standards were applicable to fewer than 1% of the incidents (see Table 2 for rank-order applicability statistics).

Table 2. Rank-ordered standards based on applicability

Additional incident characteristics

The alleged, or potential, unethical perpetrator was somewhat more likely to not be a psychologist (41.8%) than to be a psychologist (34.6%) (professional identity was unclear in 23.6% of incidents). In 54.6% of incidents, there was an attempt to informally resolve the ethical issue with the perpetrator (as prescribed in Standard 1.04), whereas 27.2% did not make an informal resolution attempt (18.2% unclear). The ethical issue was reported to a higher institutional authority 26.7% of the time (as conditionally prescribed in Standard 1.05). In contrast, incidents were not formally reported 52.2% of the time (21.1% unclear). For 35.2% of all incidents, no clear attempt was made to informally or formally resolve the situation.

Deficiency themes

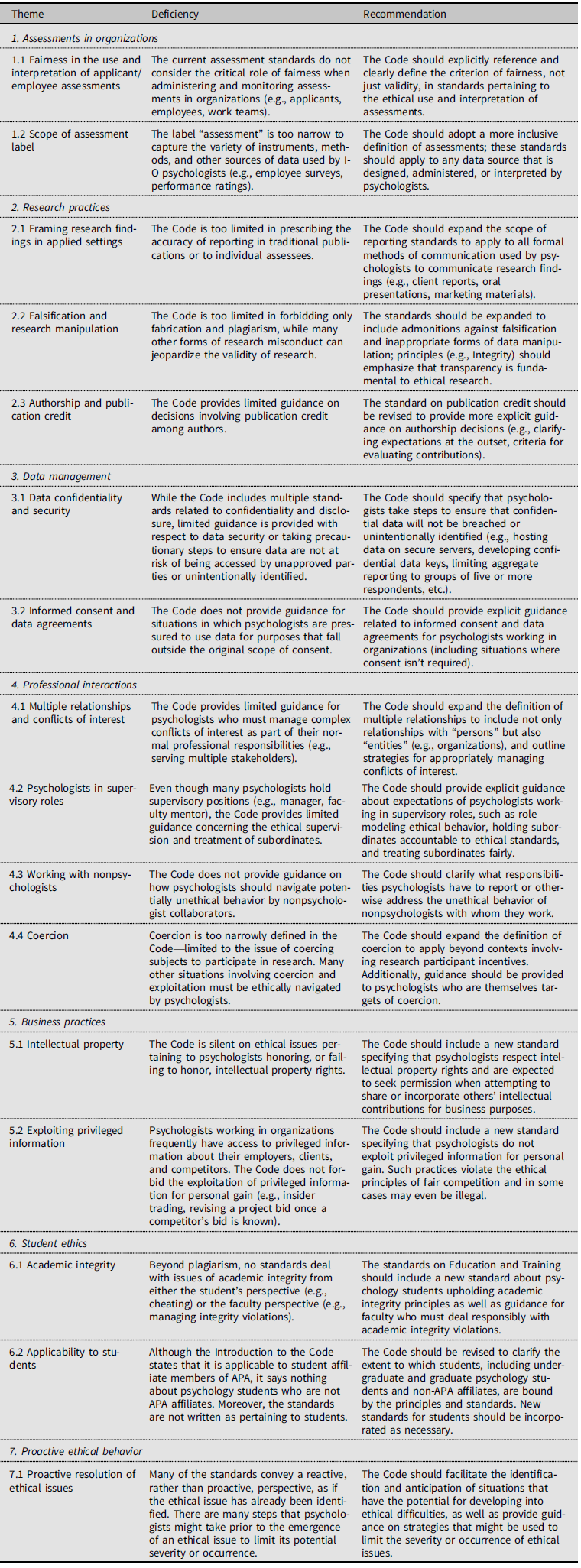

A total of 16 areas of deficiency (i.e., substantive gaps or ambiguities in the code) were extracted from judges’ comments. These 16 areas, or themes, grouped readily into the following seven higher order categories: (a) Assessments in Organizations, (b) Research Practices, (c) Data Management, (d) Professional Interactions, (e) Business Practices, (f) Student Ethics, and (g) Proactive Ethical Behavior. Table 3 presents a brief description of each theme, followed by a summary recommendation to address each deficiency.

1. Assessments in Organizations

Table 3. Themes reflecting apparent deficiencies in the Code and recommendations

The category of Assessments in Organizations was made up of two themes. Comments reflecting Theme 1.1 (Fairness in the use and interpretation of applicant/employee assessments) suggested that the code does not sufficiently emphasize the critical responsibility of many psychologists in monitoring the fairness of assessment procedures and outcomes in employment contexts (e.g., minimizing disparate treatment and the potential for adverse impact and unfair bias against protected groups in employment decisions). These ethical responsibilities extend beyond the use of individual assessments emphasized in the code and, if neglected, have the potential to negatively impact large groups of individuals as well as the organizations involved.

Comments reflecting Theme 1.2 (Scope of assessment label) capture the fact that many of the ethical incidents reported by psychologists working in organizations involved the handling of data not derived from traditional psychological assessments. Examples of alternative data sources include archival organizational records (e.g., internal human resources statistics), employee performance data (e.g., individual performance reviews), and data from employee surveys. These kinds of data sources are common in psychological research and practice in organizations, but they are not presently included among the issues covered in the code’s present standards category of Assessments.

2. Research Practices

The category of Research Practices consists of three themes. The first theme, 2.1 (Framing research findings in applied settings), criticizes the code’s focus on the presentation of research results only in traditional contexts like academic publications and presentations. Psychologists who serve as internal or external organizational consultants are frequently responsible for reporting research findings to a variety of stakeholders (e.g., clients, executives, managers) outside the traditional research dissemination context. The obligation of I-O (and other) psychologists to adhere to ethical standards regarding reporting research results, plagiarism, publication credit, and so on apply as well when addressing those nonacademic audiences, and that should be acknowledged in the code.

Theme 2.2 (Falsification and research manipulation) notes the apparent absence in the code of subtler forms of research misconduct that are not encompassed by “fabrication” and “plagiarism.” Most notably the code fails to warn against falsification, or the “willful distortion of data or results” (Fanelli, Reference Fanelli2009, p. 1). Additionally, so-called “questionable research practices” (QRPs) do not receive any attention in the code, despite their higher prevalence rates compared to fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism (Fiedler & Schwarz, Reference Fiedler and Schwarz2016) as well as growing concerns around the replicability of psychology research (Shrout & Rogers, Reference Shrout and Rodgers2018). As an example of how QRPs may affect replicability, work by Bosco et al. (Reference Bosco, Aguinis, Field, Pierce and Dalton2016) suggests that hypothesizing after the results are known (HARKing) may contribute to artificially inflated effect sizes. Additionally, Murphy and Aguinis (Reference Murphy and Aguinis2019) demonstrated that question trolling (i.e., digging around for significant effects and building a research question or hypothesis around those effects) may be particularly problematic in terms of biasing reported effect sizes. These same QRPs, among others, appeared in our data. Some examples of QRPs reported by psychologists in our sample included arbitrarily removing outliers, cherry-picking cases or variables to demonstrate a desired result, and secret (i.e., undisclosed) HARKing. We are not suggesting that the code ought to explicitly warn against every possible QRP but rather that the code should acknowledge the ongoing discussion of QRPs in the field and provide general guidelines for data transparency in research (Hollenbeck & Wright, Reference Hollenbeck and Wright2017; Vancouver, Reference Vancouver2018).

The final theme in this category, 2.3 (Authorship and publication credit), summarizes comments about ethical issues that emerged when determining appropriate credit for research contributions. Examples of issues that emerged in the incidents that are not addressed by the code include the listing of an institutional affiliation that does not accurately reflect where the work was done (despite the APA publication manual’s vague guidance to list where the author worked or studied when the work was conducted) and listing the names of colleagues on publications without their permission or awareness.

3. Data Management

The third category, Data Management, consists of two themes. Theme 3.1 (Data confidentiality and security) implicitly criticizes the lack of attention paid by the code to established precautionary strategies that can help protect the privacy and confidentiality of data managed by psychologists. Many of these precautionary strategies are widely recognized and enforced by institutional review boards for psychologists engaged in academic research (e.g., secure data storage, anonymous coding keys, best practices when reporting results in aggregate), but psychologists are frequently responsible for managing data in organizational contexts where university ethics boards have no authority.

Theme 3.2 (Informed consent and data agreements) questions the faulty implicit assumptions in the code that all research activities carried out by psychologists are subject to the traditional requirement for informed consent. The most basic tenet of The Common Rule pertaining to research with human participants is the definition of what qualifies as “research”: “The activity [is] a systematic investigation designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018; OHRP Decision Chart 1, emphasis in the original). However, I-O psychologists frequently collect data from employees for internal evaluative purposes (e.g., performance appraisal data, program evaluation data), with no intention of publishing these data or otherwise contributing to generalizable knowledge. Such situations typically fall outside the scope of traditional informed consent requirements but may involve some form of agreement explaining how data may be used, who has access to it, and other details. Further, some psychologists in our sample reported being pressured by colleagues—oftentimes executives—to use employee data for additional purposes outside the scope of the original agreement. The code provides no guidance about when such applications may or may not be permissible. We believe that authors of even such “nonresearch” studies should be held to the same ethical standards (e.g., informed consent, respectful treatment, etc.).

4. Professional Interactions

The category of Professional Interactions consists of four themes. First, 4.1 (Multiple relationships and conflicts of interest) suggests that the code’s warnings against multiple relationships and conflicts of interest are too narrow and fail to consider important nuances. For I-O psychologists, multiple relationships often extend beyond individuals such as clients, employees, managers, or colleagues, to broader entities like organizations. Multiple relationships are sometimes unavoidable in these highly complex, yet entirely legitimate roles, creating potential conflicts of interest that may not be directly financial in nature (Watts et al., Reference Watts, Gray and Medeiros2022). For example, imagine a junior consultant who is ostracized by their manager for failing to comply with QRPs that would demonstrate “positive results” to an important client. The code should acknowledge the diverse forms in which conflicts of interest can emerge, as well as offer guidance for psychologists who must find ways to ethically navigate such situations.

The second theme in this category, 4.2 (Psychologists in supervisory roles), suggests that the code provides inadequate guidance to psychologists with managerial responsibilities within organizations—a relatively common circumstance for I-O psychologists. Psychologists operating in supervisory roles have expanded ethical responsibilities, such as ensuring a work climate of fairness and respect, role modeling ethical behavior, and holding subordinates (including nonpsychologists) accountable to ethical standards.

Theme 4.3 (Working with nonpsychologists) emerged frequently in judges’ comments, perhaps because I-O psychologists are commonly responsible for collaborating with nonpsychologists (e.g., human resource staff, executives, employees, clients). As presently written (e.g., standards 1.04 and 1.05), the code does not explicitly require psychologists who observe ethical violations enacted by nonpsychologists to report these violations or otherwise address them. This raises questions: When is a psychologist ethically responsible for addressing ethical violations of nonpsychologist colleagues, and to whom might such reports be made?

Finally, Theme 4.4 (Coercion) encourages consideration of how coercion may emerge as an ethical problem outside the traditional context of academe. We observed that I-O psychologists report coercion in a number of contexts, such as when psychologists (or others) use coercion to advance their personal agenda within organizations or when psychologists are targets of coercion by executives.

5. Business Practices

The category of Business Practices includes two themes. Theme 5.1 (Intellectual property) implicitly criticizes the code’s lack of guidance around issues pertaining to intellectual property. I-O psychologists working in academic and applied contexts frequently have access to proprietary information, such as training/educational materials and assessment tools. In some cases, these materials are copyrighted and/or owned by psychologists, and in others they are owned by organizations or universities.

Theme 5.2 (Exploiting privileged information) reveals that the code fails to warn against the use of privileged information by psychologists for personal gain. Given that I-O psychologists frequently have access to privileged information (e.g., employee data, HR systems data, competitor information, confidential discussions with executives and colleagues, etc.), some respondents in our sample reported the abuse of such information by other psychologists to advance their careers or financial interests.

6. Student Ethics

The sixth category, Student Ethics, includes two themes. Theme 6.1 (Academic integrity) criticizes the lack of guidance provided in the code regarding academic integrity issues extending beyond plagiarism, such as cheating on exams and assignments. Academic institutions have their own codes so it is possible that there could be articulation issues between them. The code also provides no guidance to instructors who are responsible for appropriately responding to students’ violations of academic integrity. This seems problematic as several respondents in our sample reported an unwillingness on the part of instructors and administrators to hold students accountable for academic integrity violations.

Theme 6.2 (Applicability to students) extends the last theme by observing that the code is silent regarding its relevance to students. It is our understanding that academic departments of psychology, especially those with graduate programs, generally have adopted the code (although we have not uncovered any empirical documentation). Therefore, professors, adjunct faculty, graduate research assistants, teaching fellows, and so on, in those departments are presumably “covered” by the code. However, does the code apply to graduate students who are not affiliates of APA? Does it apply to undergraduate students? Does it apply to students only in specific contexts (e.g., when serving as a research assistant, or when holding a relevant internship)? The APA advises clinical students conducting supervised therapy that they are liable to complaints and lawsuits (Lee, Reference Lee2017)—one could infer that they are also formally covered by the code. Moreover, those standards that mention students (e.g., Education and Training category) are written from the perspective of faculty and not students.

7. Proactive Ethical Behavior

The final category we identified is Proactive Ethical Behavior, which consists of one theme. Theme 7.1 (Proactive resolution of ethical issues) suggests that the code should do more to promote ethical behavior by integrating a proactive ethical perspective throughout the principles and standards. An ethical career in I-O psychology requires not only reacting appropriately to ethical dilemmas but also foreseeing, attempting to prevent, and, if necessary, preparing for the emergence of ethical difficulties.

Discussion

For a code of ethics to fulfill its educative and enforcement functions, it first and foremost must be judged as relevant to the domain, or profession, that it seeks to guide. How does the APA Ethics Code fare when applied systematically to ethical incidents reported by I-O psychologists? In many respects, we found that the code generalized to the I-O psychology domain quite well. The fact that, on average, multiple principles and multiple standards were judged as applicable to each incident at minimum suggests that the code provides relevant guidance for the kinds of ethical issues faced by I-O psychologists, including those working in academe, internal practice, and external practice. It remains to be shown whether other APA divisions might find similar, generally supportive results.

With respect to applicability statistics, two patterns emerged. First, as anticipated, some standards almost never applied to the ethical issues reported by I-O psychologists—those in the category of Therapy. In a sense, this can be seen as running counter to the intent to create “a broader breadth and application of the Code across disciplines” (APA). But, of course, that objective is limited substantially as clinicians comprise a large proportion of the APA. One possible way to improve the applicability of the code outside clinical areas would be to integrate the Therapy standards into broader standards that already exist in other sections of the code and then tailoring the remaining standards that are not easily integrated so that they are context free. For example, Standard 10.1 (Informed Consent to Therapy) could be subsumed under standard 3.10 (Informed Consent), and Standards 10.5 through 10.8 (all dealing with sexual misconduct) could be subsumed under Standards 3.02 (Sexual Harassment) and 3.05 (Multiple Relationships).Footnote 8

A second noteworthy pattern that emerged from these applicability statistics is the fundamental relationship between the breadth of principles/standards and their applicability. As is to be expected, the (few) broad conceptual principles are far more applicable, on average, than the (many) specific standards. Moreover, this same pattern is evident within each domain—among the principles and among the standards. For example, the principles of Integrity, and Fidelity and Responsibility are framed so broadly that they are two to three times more applicable than the principle of Justice—which is the most narrowly defined of the five principles. These differences in applicability may point to natural opportunities for refinement. If an ethical principle is framed too broadly, it has the potential to lose its meaning as a distinct principle (an issue we confronted frequently when attempting to distinguish between Integrity versus Fidelity and Responsibility). In contrast, principles that are too narrowly defined risk irrelevance to the majority of ethical situations faced by professionals in a domain. For example, we found that because the Justice principle is so narrowly focused on issues of equity (i.e., a type of distributive justice), it fell short of applying to situations involving other common manifestations of justice (e.g., interactional or procedural justice; Colquitt et al., Reference Colquitt, Greenberg, Zapata-Phelan, Greenberg and Colquitt2005).

The additional incident characteristics provided some insight into the extent to which I-O psychologists reported following the guidelines presented in the code, at least with respect to Standards 1.04 (Informal resolution of ethical violations) and 1.05 (Reporting ethical violations). In just over half of all cases, I-O psychologists clearly reported that they relied on informal resolution strategies as recommended in standard 1.04 (i.e., addressing the issue directly with the violator). Meanwhile, the decision to report to a higher institutional authority (e.g., HR, committees on professional ethics, state licensing boards, etc.) clearly occurred in roughly a quarter of cases, which again aligns with the formal reporting recommendations in Standard 1.05 should informal resolution attempts fail. However, in approximately one-third of cases, no clear attempt was made by the respondent at either informal or formal resolution. Fear of retaliation is one potential explanation for this group of respondents who made no clear attempt to resolve the situation. Unfortunately, although there are some circumstances in which legal protections are provided against retaliation (for example, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act), the code presently provides little guidance to psychologists for reporting or otherwise managing potential retaliation concerns (see Keith-Spiegel et al., Reference Keith-Spiegel, Sieber and Koocher2010, for a guide for researchers that takes into account emotional and interpersonal difficulties).

Applicability statistics on their own provide an incomplete picture of the code’s relevance and how it might be improved. Thus, we observed 16 themes summarizing apparent deficiencies in the code (see Table 3). These themes spanned ethical issues encountered predominately in academe (e.g., authorship and publication credit, academic integrity) as well as issues encountered primarily in practice (e.g., working with nonpsychologists, fairness in employee assessments). However, the majority of these themes appear equally relevant to academic and applied work domains (e.g., coercion, falsification and research manipulation, privacy and security concerns, etc.). Furthermore, despite being different career paths, the boundaries between academia and practice are often blurry. For example, many areas of practice involve conducting applied research (e.g., data science, job analysis, validation) and academics often partner with organizations and employees through their research and pedagogy. Thus, we expect that all I-O psychologists, regardless of one’s professional area of work, are likely to benefit from addressing these putative deficiencies. Some of these deficiencies may be readily remedied by adding a new standard or refining existing standards to reduce ambiguity and improve generalizability. For example, adding a standard for academic integrity is a small change that would immediately increase the relevance of the code to students—a group that happens to comprise a large proportion of the total membership of SIOP as well as APA.

On the other hand, a few deficiencies uncovered “meta” issues, or conflicting general assumptions concerning how the code should be interpreted and applied. Perhaps most notably, we found that the alleged perpetrator of ethical violations in I-O psychology was more likely to not be a psychologist. If Standards 1.04 (Informal resolution of ethical violations) and 1.05 (Reporting ethical violations) are taken literally, then a psychologist who observes unethical behavior on the part of a nonpsychologist is not responsible (as far as the code is concerned) for confronting or reporting that individual. Given that such situations occurred more than 40% of the time in our sample, it can probably be assumed that such situations are prevalent in I-O psychology.

Possibly, such conflicts are unique to Div. 14, because I-O psychologists often interact with a diverse range of stakeholders who are not psychologists. However, we note that members of other psychological disciplines also interact with nonpsychologists through their work, such as developmental, counseling, or school psychologists who work with education professionals in school systems (Dailor & Jacob, Reference Dailor and Jacob2011), forensic psychologists who work with members of law enforcement or the judicial system, or, more generally, researchers who conduct multidisciplinary research.

Implications for I-O psychologists

What implications should I-O psychologists draw from these findings about applying the code to their professional decisions? First, regardless of the code’s putative deficiencies, as a practical matter it is critical to recognize that by holding membership in SIOP, I-O psychologists agree to abide by the principles and standards presented in the code. Thus, every I-O psychologist should be familiar with the code because these are the professional principles and standards by which their behavior may be appraised in the event of alleged misconduct.

At the same time, these data suggest that familiarity with the code—even following the code precisely—is not enough to ensure a consistently ethical career in I-O psychology. The apparent deficiencies uncovered point to several gaps and problems of interpretation that may emerge when I-O psychologists attempt to apply the code. As a result, it would be ill advised for I-O psychologists to limit their ethical framing to the manifest content of the code. For example, it is not sufficient for I-O psychologists who engage in academic or applied research to simply follow the code’s Research and Publication standards. By warning against only fabrication and plagiarism, these standards set a rather low bar. To be an ethical scientist–practitioner, we expect that I-O psychologists, and psychologists more broadly who engage in research activities, hold themselves to higher standards of research integrity.

Finally, even if the deficiencies identified here are addressed in future iterations of the code, it seems unlikely that any code can perfectly capture the entire domain of ethical issues that might emerge in a profession as diverse and dynamic as psychology. In keeping with its original intent, it is best not to view the code akin to a comprehensive rulebook but rather as a general guide for helping psychologists navigate ethical issues, including novel situations not covered explicitly in the code. In sum, I-O psychologists should educate themselves in the content and application of the code but recognize that following the code alone does not necessarily make one an ethical I-O psychologist; it is an important starting place.

Implications for revisions of the APA code

For members of the APA ECTF who are responsible for revising the code, the putative deficiencies and recommendations identified in Table 3 may provide some guidance. Although we relied on a sample of incidents only from I-O psychologists, we suspect that some, and perhaps many, of these apparent gaps and ambiguities might also be observed when applying the code to incidents from psychologists in other nonclinical divisions. For example, we expect that Div. 13 (Society of Consulting Psychology) and Div. 21 (Applied Experimental and Engineering Psychology) would likely encounter many similar ambiguities and deficiencies if they were to study the applicability of the code to ethical incidents in their work domains. Thus, addressing these deficiencies has the potential to increase the relevance of the code to the broader field of psychology.

Finally, APA might draw on the method presented here to periodically assess the relevance of the code to all its members. Ethical incidents could be collected from a representative sample of APA members across its divisions, and the code could be systematically applied to these incidents to identify more general deficiencies that apply to the entire field. Although the original code was drafted following the collection of critical incidents from APA members (APA, 1953), this empirical approach has been used sparsely since that time to inform revisions (Pope & Vetter, 1992). Basing future revisions on ethical incidents may help the APA to better anchor the code in the actual ethical experiences of psychologists—thereby increasing the code’s relevance, usefulness, and influence.

Ideas for commentaries

We hope this work stimulates lively discussion around the role of the APA Ethics Code in I-O psychology as well as how we can improve the ethics resources available to I-O psychologists. Here are a few specific ideas that we think could make useful contributions as commentaries:

1. Does the APA Ethics Code sufficiently capture the notion of “ethicality”? Are there other aspects of ethicality that are missing from the current version of the code?

2. Should the APA (a) expand the code to account for unique contexts in which ethical dilemmas emerge (i.e., be context and discipline specific) or (b) consolidate the code to focus on broad ethical standards that cut across contexts (i.e., be context and discipline agnostic)?

3. How can I-O psychology training programs and professional organizations better prepare students to navigate modern ethical dilemmas, so as to supplement the code?

4. Does I-O psychology need its own ethics code to supplement the APA Code?

5. What ethical decision-making models might be applied or developed to help psychologists navigate the code’s gaps and gray areas?

6. Who is ultimately responsible for ensuring that I-O psychologists are sufficiently educated about navigating ethical dilemmas (e.g., APA, SIOP, training programs, supervisors, employers)?

7. Are there similar challenges or lessons learned from ethics codes used in other subfields and disciplines (e.g., school psychology, management, law) from which I-O psychologists could benefit?

8. What can the APA and I-O psychologists in the United States learn from work psychologists operating in other countries, who oftentimes have their own associations and codes of conduct (e.g., European Association for Work and Organizational Psychology, Canadian Code of Ethics for Psychologists)?

9. What are I-O psychologists’ opinions about the relevance of the code to their work, its overall utility for the field of I-O psychology, and how it might be improved?

10. What are the opinions of psychologists from other nonclinical divisions of APA (e.g., Div. 13, Div. 21) regarding the code and recent attempts by the APA ECTF to update the code?

11. Given the limited enforcement power available to the APA for ethical issues involving unlicensed psychologists (including most I-O psychologists), how might the code be reliably enforced for I-O psychologists?

12. Given the changing nature of work, what ethical dilemmas might I-O psychologists face in the future that the code could address proactively?

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2022.112

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this work was presented at the 2022 Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology in Seattle, WA. The authors are much indebted to Deirdre Knapp, chair of the Society for Industrial-Organizational Psychology’s Committee for the Advancement of Professional Ethics; SIOP’s Institutional Research Committee and Executive Board; David Nershi; and Sertrice Grice of Org Vitality, LLC; as well as Amanda Drescher of Mercer | Sirota, for their indispensable help in approving, facilitating, and administering the survey of SIOP membership. Of course, many thanks are owed to the SIOP respondents who shared their narratives