Although ethical decision making has long been recognized as critical for organizations (Trevino, Reference Trevino1986), its importance in the 21st century continues to gain recognition in both the academic literature and the popular press due to emerging ethical issues. In academics, there is a growing effort to promote open science (Nosek et al., Reference Nosek, Alter, Banks, Borsboom, Bowman, Breckler, Buck, Chambers, Chin, Christensen, Contestabile, Dafoe, Eich, Freese, Glennerster, Goroff, Green, Hesse, Humphreys and Yarkoni2015) and reduce engagement in questionable research practices (Banks et al., Reference Banks, O’Boyle, Pollack, White, Batchelor, Whelpley, Abston, Bennett and Adkins2016) as well as to protect research participants and encourage data privacy (Shillair et al., Reference Shillair, Cotten, Tsai, Alhabash, LaRose and Rifon2015). In organizations, efforts to promote equity and inclusion in the workforce are also gaining momentum. These efforts include initiatives focused on promoting equal pay and social justice (Blau & Kahn, Reference Blau and Kahn2017; Ruggs et al., Reference Ruggs, Hebl and Shockley2020), reducing sexual harassment and potential coworker retaliation (Brake, Reference Brake2019), and reexamining practices that may serve to disenfranchise workforce members (Loignon & Woehr, Reference Loignon and Woehr2018). These points can give rise to previously underrecognized ethical choices. In addition to these social initiatives, both practitioners and applied researchers are facing increased opportunities, danger points, and pressures in the involvement of data and technology in our work. Ethical decision making is also important for preparing students of industrial-organizational (I-O) psychology for a variety of professional careers (Tett et al., Reference Tett, Walser, Brown, Simonet and Tonidandel2013).

Given the ethical challenges that have long faced I-O psychologists in the variety of roles we fill in education, research, and practice, an ethical decision-making framework and examples of applying the framework to everyday experiences are much needed in the ever-evolving environments in which we work. This article was developed by the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP) Committee for the Advancement of Professional Ethics (CAPE). Established in 2017, our primary goals are to provide instructional resources to help I-O psychologists make ethical decisions in the workplace and to promote discourse related to ethical decision making in our field.

Decisions with ethical implications are not always readily apparent and often require consideration of competing concerns. CAPE seeks to provide professional development resources to help I-O psychologists successfully identify and navigate through such gray areas. Moreover, the American Psychological Association (APA) Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct are the principles and standards to which all SIOP members (regardless of whether they are also APA members) are held accountable. CAPE serves SIOP stakeholders by helping them understand and apply the APA’s code of ethics to their work.

To this end, the primary focus of this article is the development and presentation of an integrative ethical decision-making framework rooted in and inspired by empirical, philosophical, and practical considerations of professional ethics. The purpose of this framework is to provide a generalizable model that can be used to identify, evaluate, resolve, and engage in discourse about topics involving ethical issues. To demonstrate the efficacy of this general framework to contexts germane to I-O psychologists, we subsequently present and apply this framework to five scenarios, each involving an ethical situation relevant to academia, practice, or graduate education in I-O psychology. Although we recognize and anticipate that readers may be interested in responding directly to the minutia of specific situations and potential solutions, we are hopeful that the commentaries supplementing this focal article will direct more attention toward using these situations as stimuli for the refinement of the ethical decision-making framework, its application in our profession, and more generalized conversations about ethical practices.

Conceptual framework: The ethical decision-making process

Here we present a conceptual framework of the ethical decision-making process. Ethical decision making involves adherence to accepted moral standards (Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2006). In constructing this framework, we targeted a goal of parsimony so as to make the content accessible and easy to apply. We drew upon a variety of sources in the creation of this framework, including the APA’s code of ethics, scholarly books (e.g., Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Beauchamp and Bowie2012; Hartman & DesJardins, Reference Hartman and DesJardins2011; Lefkowitz, Reference Lefkowitz2017), and journal articles (Bush, Reference Bush2019). Consequently, our model is certainly not the first of its kind but is meant to serve as a user-friendly resource to the SIOP community. We reviewed and integrated existing models and abstracted a simple version that captures the essence of the state of the literature.

The APA Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/) serves as the background for the current work. The APA’s code of ethics specifies five aspirational principles: (1) Beneficence and Nonmaleficence, (2) Fidelity and Responsibility, (3) Integrity, (4) Justice, and (5) Respect for Human Rights and Dignity. There are 10 sections with specific behavioral standards that cover topics ranging from Resolving Ethical Issues (Section 1) and Competence (Section 2) to Human Relations (Section 3) and Assessment (Section 9). The APA’s code of ethics is intended to be applicable to all psychologists, regardless of disciplinary focus or work setting with the exception of Therapy (Section 10), which is explicitly targeted to health care practice. During the period in which the present paper was being written, the APA’s code of ethics was undergoing revisions; however, we do not anticipate that it will fundamentally alter expectations for the ethical behavior of psychologists. Moreover, we are hopeful that the revised code will be more easily applied to the day-to-day practice in our roles as I-O psychologists and that stakeholders will be actively involved in responding to proposed changes as they are released for comment to help ensure that this is the case.

Ethical decision making compared with other types of decision making

Theoretical models for decision making, such as those based on normative decision theory (Brennan, Reference Brennan1995; MacCrimmon, Reference MacCrimmon, Borch and Mossin1968) or image theory (Morell, Reference Morrell2004), are common and have a rich history in a number of scientific areas. These models share some similarities to ethical decision-making models, such as a decision-making process that seeks to maximize utility and minimize bias (Guala, Reference Guala2000) and emphasis on the need to account for norms (MacCrimmon, Reference MacCrimmon, Borch and Mossin1968). These models also help one consider how to compare and weigh alternative choices (e.g., Morell, Reference Morrell2004). However, they do not adequately address or reflect many of the unique elements of ethical decision making. For example, ethical decision making is often characterized as a more active versus reflexive judgment process (Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2006) in that it requires one to actively recognize, monitor, and (re)evaluate the issues and outcomes of actions as they unfold. Furthermore, ethical decision making most commonly involves the well-being of others as a critical criterion in the evaluation process as well as active consideration of how to resolve dilemmas in which there are competing interests/consequences across multiple stakeholders (including one’s self). Last, the instrumentality of actions/decisions is often simultaneously informed by legal, professional, or moral standards held by different societal and cultural groups, which may both aid and introduce additional complexity to the ethical decision (Kohlberg & Hersh, Reference Kohlberg and Hersh1977).

We begin our description of the ethical decision-making process with some important caveats and background information. First, ethical decision making is often thought to be straightforward. It may appear that, based on the APA’s code of ethics, the correct course of action is quite clear though potentially difficult to act upon (Bush, Reference Bush2019). We expect that the present decision-making framework will be most useful when this is not the case. Second, the framework at a minimum should increase sensitivity to ethical issues (Yetmar & Eastman, Reference Yetmar and Eastman2000). We operate under the assumption that the vast majority of I-O psychologists want to be ethical and “do the right thing.” This is based on a wealth of research from different disciplines that most people are ethical but could benefit from help thinking through their decision making (Ariely, Reference Ariely2012). Third, ethical norms can change over time. We expect that the framework presented is relatively robust to changes, such as revisions to the APA’s code of ethics. Over time, however, there may be an unknown expiration date at which point this framework may need to be updated.

Fourth, the results one achieves at each stage of the framework will inevitably be sensitive to individuals’ personal values, those of their organization, and society at large. For example, SIOP members pledge to adhere to the APA’s code of ethics when attempting to determine whether an ethical situation exists and how best it might be handled (American Psychological Association, 2020). Nevertheless, we propose that the decision points and considerations highlighted in the ethical decision-making framework are indifferent to applicable professional guidance or one’s philosophical perspective. That is, the framework can serve as a cognitive decision-making aid irrespective of an individual’s subjective stance on a given matter.

Fifth, applying an ethical decision-making framework takes practice. We encourage readers to consciously consider ways this framework can be applied in their work lives and learn from the experience of applying it. Sixth, readers should consult additional materials beyond what is presented in this article. Most notably, this includes the APA’s ethics code (Bush, Reference Bush2019). We intentionally drew upon seminal and recent references in our citations so that our reference list could serve as a reading list for those who wish to teach or learn in greater depth about any particular issue. Additional readings can be found on the CAPE website (https://www.siop.org/Career-Center/Professional-Ethics). Last, although this framework is presented in a linear fashion, ethical decision making frequently occurs in a recursive fashion. That is, ethical decision making should be viewed as a process in which one may need to revisit and reconsider the conclusions generated in particular phases of the framework as a situation unfolds, additional information is uncovered, and/or consequences are realized.

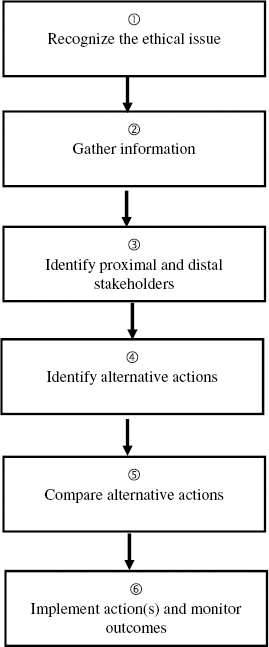

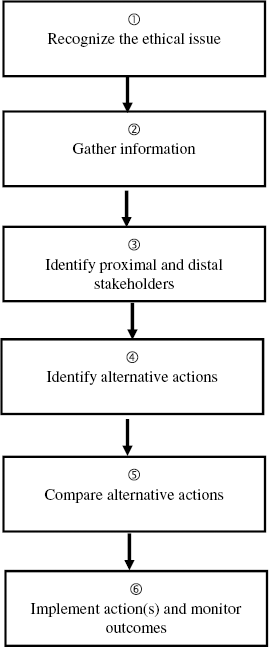

The first stage of our proposed framework involves identifying or recognizing the potential ethical issue(s) present in a given situation or decision (see Figure 1, Stage 1). Colloquially, the consideration of ethics involves often defining what is considered “right versus wrong” or “good versus bad” conduct. Furthermore, judgments of ethical matters are typically interpreted with respect to particular moral principles or values-based standards, and thus the consideration of ethics also frequently involves appeals to the standards used to evaluate a matter’s ethicality. For purposes of our framework, we characterize a situation as clearly involving ethical considerations if they are addressed by APA’s principles and standards (https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/). We elected to purposefully restrict our discussion to a consideration of ethical issues in the context of APA’s code of ethics—as opposed to other possible value frameworks—as these are the professional principles and standards of conduct endorsed by SIOP and its membership. In this admittedly oversimplified view, the first stage involves simply recognizing that the APA principles or standards apply to a particular decision. Although the APA’s code of ethics explicitly states that conduct not specifically addressed by the standards is not by definition either ethical or unethical, the principles are more general in nature and can help psychologists identify areas to which they should be sensitive.

Figure 1. Ethical decision-making framework. Note. The ethical decision-making framework was based on an integrated review (e.g., Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Beauchamp and Bowie2012; Hartman & DesJardins, Reference Hartman and DesJardins2011; Lefkowitz, Reference Lefkowitz2017).

The first stage becomes considerably easier as familiarity with applicable ethical standards (in this case, the APA’s code of ethics) increases. Initial recognition and acknowledgement of an ethical situation should prompt one to gather more information (see Stage 2 in the framework) and ultimately consider additional stakeholders who may be affected (see Stage 3 in the framework). This may necessitate considering the decision that produces the most favorable outcomes for the majority of stakeholders involved. However, it might also include defending processes used to make decisions to protect the rights and well-being of individual stakeholders, particularly when there are imbalances in power among the involved parties.

As awareness and recognition of ethical issues improves over time, this stage should become more familiar to us, and it will be increasingly clear that the extent to which a decision is ethical in nature falls along a continuum. Decisions are rarely a dichotomy in which there is clearly an ethical issue or there is not. For example, Hartman and DesJardins (Reference Hartman and DesJardins2011) argued that the extent to which a decision will influence the well-being of those involved determines the extent to which a decision is an ethical decision.

For SIOP members, familiarity with the APA’s code of ethics will help identify ethical situations and therefore increase the likelihood of actions that are in accordance with the code. Knowledge of the APA’s code of ethics; relevant organizational policies; and applicable local, state, and federal laws partnered with an understanding of how to use the framework will help navigation through situations where the moral choice is not clear. However, it is also important to be aware of biases that can prevent or challenge our ability to recognize a decision as having an ethical component. For instance, normative myopia (Swanson, Reference Swanson1999), characterized as a tendency for an individual to downplay ethical values in decision making (Orlitzky et al., Reference Orlitzky, Swanson and Quartermaine2006), may prevent us from seeing a decision as ethical in nature because our attention is fixated on the business at hand or our scientific contribution. In other words, we might become so focused on the responsibilities we bear for meeting the needs of an important client or achieving a professional goal that we fail to see how a professional decision might influence the well-being of distal stakeholders.

Other challenges may occur that prevent us from recognizing ethical situations. Change blindness, defined as an inability to detect change (Simons & Levin, Reference Simons and Levin1997; Simons & Rensink, Reference Simons and Rensink2005), may similarly render us unable to recognize the evolution of a situation over time from one that appears to be a straightforward professional decision to one that presents an ethical conflict. Last, empirical evidence shows that conflicts of interest influence our ability to make ethical decisions (Ariely, Reference Ariely2012). Simply being familiar with the APA’s code of ethics can be a useful strategy for sensitizing ourselves and those we work with to avoid the slippery slope of potential ethical potholes that can derail otherwise conscientious professionals.

The second stage in our model of an ethical decision-making process is the gathering of information (Figure 1, Stage 2). Gathering additional information allows a fuller view of the situation and potential ethical implications and also begins to highlight relevant stakeholders and possible outcomes that might result from any given decision. There are various ways in which more information may be collected. For instance, we may look at past precedent; engage in formal or informal conversations with others; collect additional data; or review relevant contracts, policies, regulations, or laws. Oftentimes the nature of the information we collect pertains to outcomes (e.g., how stakeholders are or might be affected) as well as processes (what rules or regulations exist regarding how decisions are executed).

The third stage of our framework concerns identifying stakeholders of the ethical decision (Figure 1, Stage 3). We define a stakeholder as anyone who may be affected by a given decision or action taken to resolve the ethical issue. In academic work, stakeholders may include fellow researchers, faculty, students, the institution where a person is employed, and the individuals or organizations who participate in or fund research. In practice, stakeholders can include organizations with whom a person works (either as a consultant or employee) and individuals associated with those organizations (e.g., coworkers, employees, applicants, coaching clients). Stakeholder groups could also be as broad as the general public or our profession at large. Stakeholder theory provides a rich discussion of stakeholders and how to optimize stakeholder outcomes (for a review see Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Bosse and Phillips2010). Some stakeholders may be more proximal to the decision and thus can be easily recognized. However, distal stakeholders may also be influenced by outcomes of a decision and thus deserve consideration in the decision-making process.

It is often in the process of collecting information that we learn about both proximal and more distal stakeholders. Thus, identifying stakeholders often comes after gathering information. There can be a tendency to focus on those immediately within our purview and therefore fail to consider those less immediately affected. Thus, this stage in the process requires caution and care to make sure that we are thorough in our considerations. This again illustrates that the framework may not always be applied in a strictly linear fashion. For instance, identification of stakeholders (Stage 3) may often lead to more data gathering (Stage 2).

Fourth, one needs to consider available alternative actions (Figure 1, Stage 4). Satisficing is commonly discussed in this context (Sanders & Carpenter, Reference Sanders and Carpenter2003). Here, one may search for available alternatives and select the first alternative that meets a minimum criterion of acceptability, thus ending the search for alternatives (Ward, Reference Ward1992). The concern here is that other available alternatives may be superior but are never identified. In practice it may not be possible to identify every possible alternative, and thus creativity and expertise often play an important role in the ethical decision-making process to ensure that as many reasonable alternatives as possible are considered (Bierly et al., Reference Bierly, Kolodinsky and Charette2009; Dane & Sonenshein, Reference Dane and Sonenshein2015). Importantly, we might sometimes delay ethical decision making in order to identify additional alternatives. However, a balance must be struck, as an important element of the ethical decision-making process is often the timeliness of the response. Consequently, we must weigh the need to identify all reasonable alternatives against the challenge of also making timely decisions.

The fifth stage in the framework is to compare and weigh the identified alternatives (Figure 1, Stage 5), and this commonly necessitates considering multiple perspectives simultaneously. This is another point in which the APA’s code of ethics might feature prominently in the decision-making process and serve as a guiding framework (APA, 2017). The APA’s code of ethics can provide important clarity in ambiguous situations. However, they do not provide easy answers to difficult decisions that require making compromises among competing interests or stakeholders. As with all facets of ethical decision making, seeking input from trusted colleagues can be an important strategy to support ethical decision making, particularly in high-stakes situations.

The final stage of our proposed framework includes implementing the chosen decision and monitoring associated outcomes (Figure 1, Stage 6). Implementing an ethical decision can be difficult for a number of reasons. It may be more difficult because others with whom we work may disagree with the decision we choose to make or because it will require uncomfortable interactions. There may also be conflicts of interest (e.g., between self-interests and the interests of others), lack of information, lack of formal authority, or even differences in values that complicate execution of an ethical choice.

Taking responsibility for tracking the effects associated with the choice once it is executed is an important element of this stage because it allows refinement of the decision over time and improves future decision making (Kaptein, Reference Kaptein2015). That is, ethical decision making is a dynamic process, and many situations require continuous monitoring to ensure that an effective decision was made. Therefore, it is important to reflect on the decision and associated outcomes as time passes and consequences are realized. Monitoring allows us to judge components of the decision to rectify or revise previous choices and improve future ethical decision making.

In summary, the ethical decision-making framework offered here, although parsimonious, highlights the full “life cycle” of an ethical decision. Although the framework does not—and cannot—give an answer to any specific ethical issue, we believe it provides a means to help guide the process of making ethical decisions. In the next section, we demonstrate how this framework could be applied to five example cases germane to I-O psychologists.

Application of the ethical decision-making framework

In the following sections, we apply the proposed ethical framework to situations from academics, practice, and graduate school. As previously noted, our intention is not to provide “answers” or suggest what we believe is the one “correct” way to handle such scenarios. Rather, our goals are to provide readers with (a) opportunities to consider and reflect on how situations involving ethical issues might be navigated, (b) examples of how the proposed decision-making framework could be used to facilitate this process, and (c) materials to stimulate further discussion and discourse regarding professional ethics in I-O psychology. We also hope that this presentation highlights the nuances that emerge during ethical decision making as one considers each of the steps described in our framework.

Situation #1: A situation of potential plagiarism

Over the course of the last year and a half, Taylor, an associate professor, has been coediting, along with Joyce, a seminal book on leader cognition. Taylor has been fortunate to be included in this effort that has amassed an all-star lineup of authors, including up-and-coming and senior experts in the field. Due to Taylor’s work on a recent manuscript that reviewed the literature, she has also contributed a chapter for the book. This initiative offers an excellent opportunity to further Taylor’s career aspirations and receive recognition for her work. Although the process of writing the chapters and getting them ready for publication has been a long one, Taylor has finished her section and after one last look through all her materials, sends it to her coeditor Joyce in an email. After a few hours, she receives a reply thanking her and letting her know that Joyce views the project as not only a major personal success but also one that will have a positive effect on Taylor’s budding career prospects as well as those of the other contributors to the book.

However, the next day Taylor receives an email from Parker, a contributing author to the book, informing her that Grayson, also a contributing author, recently had multiple articles retracted from several places over concerns of self-plagiarism. Parker indicates that he did not want to go to Joyce with this information because he was unsure that it was actually true. Taylor has no reason to believe that Parker is lying about the situation, yet she finds it odd that Grayson—one of the most well-known names and leading experts in his area of expertise—would engage in this practice.

In this scenario, the apparent ethical issue concerns Grayson’s recent acts of self-plagiarism, the extent to which those behaviors are reflected in Grayson’s contributions to the current book, and the effect they may have on the credibility of the book and the other contributing authors’ efforts (Figure 1, Stage 1). The APA manual characterizes self-plagiarism as presenting your previously published work as though it were new (APA, 2020). Therefore, there are standards that can be used to help interpret the extent to which this ethical violation might have occurred in Grayson’s work for the book.

Taylor’s recognition of the ethical dilemma leads her to Stage 2 in the ethical decision-making framework—that is, gathering information (Figure 1, Stage 2). Taylor could attempt to seek information to confirm whether Grayson had one or more articles retracted. Taylor could also ask Parker whether he is aware of which work may have been plagiarized or how the editors of those sources that retracted Grayson’s previous work made their determinations.

The next stage in the framework is to identify potential stakeholders (Figure 1, Stage 3). Proximal stakeholders include Grayson, any of Grayson’s coauthors, Parker, and Joyce, as well as other authors who contributed to the book. More distal stakeholders might include the publisher of the book, the publishers of journals where Grayson’s work may be plagiarized, and Grayson’s other coauthors.

Fourth, Taylor should consider potential courses of action (Figure 1, Stage 4). This might include contacting Joyce to discuss the situation. Taylor could also send an email to Grayson and Grayson’s coauthors on the chapter to request additional information and to make them aware of the situation. As another option, Taylor or Joyce could run the chapter through a plagiarism detector. This option offers a quick check that would give Taylor a sense of the potential degree of self-plagiarism. Taylor and Joyce may have to reach a joint decision on how to proceed and involve the publisher in their conversations.

Taylor’s next stage would be to compare and weigh alternative actions (Figure 1, Stage 5). Here again the APA principles and standards related to plagiarism can serve to help evaluate which of the previous alternatives are most viable. These standards are useful in helping Taylor determine how to define self-plagiarism and the extent to which it occurred. However, Taylor and Joyce would then have to use that information to make an informed decision about whether the chapter needed to be removed and how each stakeholder would be affected. In the sixth stage of the ethical decision-making model (Figure 1, Stage 6), Taylor again can contact Joyce and the publisher to consider further options. This might include delaying production of the book to allow for removal of the chapter. Footnote 1 Taylor and Joyce could consider keeping Grayson as an author if there is not sufficient evidence that he self-plagiarized or the redundancy was sufficiently minor that it could be addressed prior to printing. Ultimately, Taylor and Joyce would need to consider how to communicate and implement the decision in order to be fair to all stakeholders.

Situation # 2: Authorship on academic work

In this situation, Peter is an untenured assistant professor who has recently begun a position at a research university. Peter is approached by a late-stage doctoral student, Susan, who asks if he is free to grab a coffee to talk about a sensitive matter. Over coffee, Susan brings up a meta-analytic review that she has been working on with Peter as a part of her graduate assignment (GA). There had been no formal discussion about contributions on the paper. Her role had involved systematically searching the literature for articles and coding results in articles.

Susan recently found out that Peter’s coauthor Derek, another assistant professor and the project leader, did not expect to include her as an author on the paper. His explanation was that the work she completed was paid work as part of her GA. Moreover, he did not consider downloading articles and coding to be intellectual work. Susan privately disagreed, citing that she created the systematic search strategy, identified critical key words to be used, and constructed the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the samples. She also argued that she played a role in developing the coding sheet, which itself was an intellectual contribution. To make matters worse, she found out that Megan, a senior professor, was being added as an author. Susan confides in Peter that she suspects Derek is attempting to win favor in terms of his upcoming tenure and promotion packet and to increase the likelihood of publication by adding Megan, a “big name scholar,” to the paper. Yet, Derek simultaneously wants to keep the number of authors small to maximize the amount of credit he will receive. Susan asks for Peter’s advice regarding how to move forward.

In the first stage of the ethical decision-making framework, recognition of the ethical issue occurs. Drawing from the APA guidelines, the apparent ethical dilemma primarily concerns deciding on the meaning of intellectual contribution and its role in determining authorship in a scholarly work (for details on authorship considerations, see https://www.apa.org/research/responsible/publication/). Peter might consider the extent to which Susan’s well-being and her professional status may be affected. Peter might also consider if there are any potential biases or conflicts of interest that might influence him or others in this decision-making process. Given that Peter knows all parties involved and is a coauthor, conflicting interests may play a role in his decision making. It would seem, given the concerns raised by Susan, that this is an ethical issue in which, at a minimum, it must first be determined whether or not Susan has earned intellectual credit for her work on the project.

The second stage in the ethical decision-making framework directs one to collect information. In this case, Peter might ascertain additional relevant facts related to Susan’s role on the project (e.g., more details on the tasks she has completed, the nature of her specific contributions), clarity regarding APA standards on authorship, and whether there are policies in place at the university regarding faculty–student collaborations. To answer these questions, Peter may need to ask the student more pointed questions about her work and also consider others he should speak with about the matter, particularly given his self-interests in this situation.

At this point, Peter may contemplate proximal and distal stakeholders (Stage 3 in the framework). It is apparent that Susan, Derek, Megan, and Peter himself are primary stakeholders. Peter might also consider other graduate students in the program to be stakeholders given that they also work on GA assignments that may or may not lead to authorship contributions. If Peter were to consider more distal stakeholders, he could also account for the journal to which the paper might be submitted (e.g., do they have an authorship or contributorship policy), other researchers at his university, and the university itself.

The next stages of the ethical decision-making framework indicate that Peter should identify (Stage 4) and compare (Stage 5) alternatives for addressing the issue. Although it makes sense for Peter to consider alternatives, Derek and Megan should also be involved in the conversation because all are coauthors. Peter could discuss potential options with Susan for appealing to Derek and the author team, as well as the department chair and PhD program coordinator if she desires. In doing this he should also reflect on several questions. What might this do to professional working relationships? Is this also a constraint in the decision-making process? What about backlash within the department?

Reflecting on these questions might clarify the consequences of certain decisions but may also highlight constraints in how the issue is perceived, evaluated, and considered. Peter might also consider how he and Derek have handled student roles on projects in the past. The most immediate standards Peter should consider include the APA Publication Style Manual (2020), which explicitly discusses authorship. APA does consider data collection a form of intellectual contribution but also states the need for a scholarly element to the work. Simply conducting manual labor may not count in many instances.

In the sixth and final stage, Peter would implement the decision or advise the student on how to go about implementing the decision. In this context, Peter does not have sole decision-making authority and may even have to defer to Derek. This is because Derek serves as the project lead and was more involved in supervising the data collection process. Peter could make a recommendation to the author team or offer to serve as a mediator for subsequent conversations. Peter might take additional steps and encourage other faculty and students to discuss authorship and what constitutes an intellectual contribution at the start of a project. This last stage may serve to reduce the likelihood that this issue would occur again. Although university research integrity officers may not see authorship disputes as a research integrity issue, there are still important ethical elements to these types of decisions.

We wish to point out that even though the current case focuses on what might be a traditional academic context, it is relevant for practitioners as well. Even in a nonacademic context, assignment of credit for intellectual contributions is something that spans all nature of work. Consequently, transparency and open communication is needed to ensure that assignment of credit follows whatever norms are appropriate for the context and that the final outcome is fair to all involved parties.

Situation #3: A coaching engagement

Sophia is an I-O psychologist in a midsize corporation and for the past 5 years has been responsible for developing talent management tools and programs for internal use. She has been revamping a multirater feedback process geared for senior managers, and the executive team has asked that she provide participating managers with coaching following receipt of their feedback reports. Sophia does not have specialized training in this area, but her suggestion that an external consultant be engaged to handle this coaching task was rebuffed by the executive team as being unnecessary and too expensive. Sophia is excited about this opportunity to add another dimension to her work responsibilities and feels that, despite her lack of formal training, she will be able to strengthen the value of the feedback report by supplementing it with her insights. Besides, this would not be an extensive coaching engagement but rather one discussion with the possibility for follow-up conversations tied closely to multirater feedback reports.

Referring to Step 1 of our decision-making model, it is apparent that Sophia knows she is on shaky ethical ground if she were to provide the coaching herself because her first instinct was to recommend that her employer hire an external consultant to do this work. If she were to refer to the APA’s code of ethics, she would also find standards relevant to this situation. Conflicts between ethics and organizational demands (Standard 1.03) and boundaries of competence (Standard 2.01) are certainly applicable. She could also consult professional guidelines that address the specialized area of coaching to help determine whether she is facing a decision with ethical implications.

In the second stage, the model suggests gathering information (Figure 1, Stage 2). In addition to consulting professional ethics codes, the company that Sophia works for may also have an ethics code that should be consulted for guidance. Sophia might also do more targeted research into what distinguishes professional coaching from the type of performance feedback session that a manager might give to staff members following receipt of a multirater feedback report and how her assignment would fit into that scheme. She could also consult professional colleagues who might have informed perspectives to consider in this situation.

In the third stage, the model suggests identification of stakeholders (Figure 1, Stage 3). Of course, Sophia is herself a stakeholder. Naturally she wants to behave in a professionally responsible way and still be responsive to the needs of her employer. The executive team is a stakeholder, as are the managers who will be participating in the new multirater feedback process. More distal stakeholders include the current and future staff members reporting to those managers and the functional departments that the managers lead.

The fourth stage of the model proposes identification of possible resolutions to the ethical problem (Figure 1, Stage 4). Depending on what Sophia learns through her information-gathering stage, she may be able to generate solutions beyond simply accepting or declining the direction of her executive team. For example, she could propose creating an explicit protocol for handling performance feedback sessions that constrain her role as a “coach” and restrict the interaction to a single session focused specifically on the feedback results. Or, based on the feedback report results and perhaps additional information, she could identify a small number of managers most likely to benefit from coaching to minimize the cost of hiring a suitably trained external consultant. Still another potential strategy would be to make a case for the corporation to support the additional training and possibly professional certification for Sophia that would help ensure her competence to offer professional coaching services to the firm’s managers.

The fifth stage of the model suggests comparing potential decision alternatives generated in the previous stage (Figure 1, Stage 5). Here, Sophia might want to return to trusted colleagues within and/or outside her company to help think through the pros and cons of various alternatives before taking action. If there is a member of the executive team with whom Sophia feels comfortable enough, she could float ideas with that individual before deciding how to proceed. This is also where contextual information could factor significantly into her decision making. Are certain options more or less consistent with the firm’s culture and decision-making norms?

Finally, the last stage of the ethical decision model is when Sophia implements her final decision and monitors the associated outcomes (Figure 1, Stage 6). Whatever her decision, how she implements it (e.g., how and with whom she communicates it) could be an important factor in its success. The reaction of her executive team will likely be the first outcome of interest and might require her to adjust her plans. One strategy for purposefully monitoring subsequent consequences of her actions would be to collect evaluation information on the new multirater process, with particular attention to any associated feedback or coaching sessions regardless of how that portion of the process ends up being conducted.

Situation #4: External consulting/research practice

Jayden is an I-O psychologist at a private research institution that specializes in program evaluation for training and development programs. Occasionally, his team works on other types of programs, such as marketing and advertising campaigns. Recently, Jayden was assigned to a project to evaluate the effectiveness of a retail company’s new sales promotion program that was launched in 30% of the company’s stores over a period of 5 months. His client contact, Grace, made it clear to him that the results would be critical to the performance evaluation of the team that had worked hard to put the promotion program together. When Grace turned over the data, it was obvious that the information was not appropriately collected and maintained. Many data points were missing or otherwise potentially problematic (e.g., out-of-range or unlikely values). Jayden tried to work with Grace to understand what had happened during the data collection process, but Grace insisted that he could use his judgment to figure out the data issues. Grace also suggested that she could give Jayden more data if the p value hadn’t reached the level of significance. Jayden tried to explain that a p value is not the only critical component in program evaluation and that there might not even be enough data to test for statistical significance. Grace responded that, based on her expertise in sales promotion campaigns, she is certain that there is always an effect somewhere in the data. As he is pondering ways to approach this, Jayden gets an email from his manager, telling him that he has spent too much time on the project and needs to wrap it up.

Jayden recognizes that there are competing interests in this situation, so the ethical decision-making framework may be a useful tool for him to use. Per Step 1, an obvious ethical issue is that a client is pressuring him to analyze faulty data and cherry pick the results, which he knows would be wrong. He may need to spend additional time on the situation, but his manager is urging him to deliver results quickly. There may be technical strategies to mitigate the situation (e.g., redefining the sample within an incomplete dataset), but his own lack of experience in this type of evaluation may be another ethical issue. If he refers to the APA’s ethics code, he would find the behavioral standards at play to include conflicts between ethics and organizational demands (Standard 1.03), boundaries of competence (Standard 2.01), and bases for scientific and professional judgments (Standard 2.04).

Gathering facts, as suggested in the second stage of the model (Figure 1, Stage 2), should lead Jayden to seek out additional information. For instance, Jayden could research how other marketing-oriented program evaluations are conducted and how others have dealt with similar situations. Jayden would presumably also inform his manager of this situation both to determine how this information affects his guidance to quickly finish the project and whether his manager has additional direction he wishes to provide. Jayden might also find out whether others in the company have worked with this client and how they managed the process. In this situation, it would be important to learn whether Grace understands the potential consequences if inaccurate results are provided to her company. Jayden should also consult the contract between the client and his employer to determine whether it has language relevant to the situation.

The third stage of the model suggests identification of stakeholders (Figure 1, Stage 3). Stakeholders for the current situation include Jayden, Jayden’s employer, and the client organization. Jayden is presumably concerned about the ethics of his own behavior as well as his standing with his employer. His employer may be concerned about its own reputation for quality work but also about the financial bottom line. Although Grace is the client representative, she is part of a team (which she wants to look good) and an organization that would ultimately be ill-served by inaccurate findings from this evaluation.

In the fourth stage, the model suggests that Jayden identify alternative solutions to the ethical problem (Figure 1, Stage 4). For example, perhaps Grace would be more amenable to addressing the data accuracy problems (or identifying someone who could do so) if she understood that the sample sizes would be too small to achieve the statistical power needed for significance testing with the available data. Furthermore, until the analyses have been conducted, it is not clear what they will show. If they are not favorable, Grace might be more receptive to Jayden’s manager (instead of Jayden) conveying the message that there is only so much that can be done within the bounds of professional integrity to change the findings. In any case, although Jayden is responsible for his own behavior, he should involve his manager in addressing this situation because it involves a contractual matter as well as an ethical one.

The fifth stage of the model suggests comparison of alternative solutions from the previous stage (Figure 1, Stage 5). Conducting additional research and inquiring for information will require additional time. Therefore, Jayden may choose to present the new information that has been gathered, but the client and his manager may not like the fact that he is spending more time on this project. Jayden might choose to engage in a candid conversation with the client to resolve potential misunderstandings, which has the potential to exacerbate the issue. Another option might be for Jayden to request to be removed from the project. This may seem like a favorable option, but it could also result in other team members considering him to be incompetent and unable to resolve tough issues.

In this scenario, it would be reasonable for Jayden to consider planning a series of increasingly bold actions depending upon how things develop. For example, he could show Grace what the results are looking like with the faulty data and explain how cleaner data would help. If she pushes back, this could be the time for his manager or another more senior representative of his company to step in to manage the situation. If he does not find support from his employer or his client in this situation despite repeated efforts to point out the ethical issues, the APA’s code of ethics does not require him to risk his job over the matter (See Standard 1.03).

The last stage of the ethical decision-making model suggests implementation of the decision and monitoring of the associated outcomes (Figure 1, Stage 6). As the situation unfolds, Jayden may need to adjust course. Whatever the ultimate outcome, Jayden might consider what lessons he could learn from this situation that will help him in the future. For example, he might ask for additional assistance or prepare himself through self-study when starting a project that is outside of his experience. He might check in with clients to ensure data are being collected and recorded properly early on to help avoid data-related problems that will be difficult or impossible to fix after the fact. As a result of this experience, Jayden may also recognize that clear and frequent documentation of decisions, agreements, and progress made through the course of a project could also provide the support needed to push back against unreasonable requests.

Situation #5: A situation of sexual harassment

Allison was considered by all in her graduate program to be hardworking and quick to help others, and she polished her reputation working with her advisor, Dr. Fellows, an esteemed and senior male professor. Dr. Fellows tends to be brusque with his graduate students, although people also whisper about his provocative behavior toward young women. Perhaps because of his strong academic reputation, nobody has said much beyond whispers.

Allison recently sat down with Dr. Fellows to go over the most recent set of observations from a project they were conducting together. Before beginning, he tells her that he has received a grant related to the project topic and that he is strongly considering her as the grant lead, which may increase her research opportunities after she graduates. He proceeds to tell her that they will likely need to spend a lot of time prepping study details and materials and that the best time for them to meet will be at the end of the workday. She knows how busy both of their schedules are and does not think much of the suggestion at this point.

Allison decides that further networking with Dr. Fellows and the rest of his research team would be helpful. Up to now she has declined invitations to the weekly happy hours with the other students, but Allison decides that this type of event might afford a more relaxed atmosphere and she might find an opening to demonstrate her interest in the work and grant. She mentions to Dr. Fellows that she will be joining the happy hour group. Surprisingly though, he suggests she come later, around 7:00 p.m., when the group usually begins breaking up. She arrives at 7:00 p.m. and orders a drink. Dr. Fellows is clearly quite intoxicated and begins to tell a number of off-color jokes with sexually explicit content and with Allison as a target of several of the comments.

Allison now finds herself in what she perceives to be a seriously uncomfortable and compromising situation with ethical implications (Figure 1, Stage 1). Allison decides to leave immediately before things can get worse from her perspective. She excuses herself and heads home. The next day she receives an email from Dr. Fellows addressed to the whole lab. The email announces that another graduate student will be leading the new grant. Allison is simultaneously frustrated and disappointed. She wonders whether the decision was a direct result of the incident that occurred at the lab happy hour the day before. Elements of the APA’s code of ethics relevant in this situation include standards related to harassment, the principles of respect for people’s rights and dignity, and justice.

Allison’s next step, in line with the ethical decision-making model, is gathering information (Figure 1, Stage 2). One initial action for Allison can include reviewing the university’s sexual harassment policy and procedures as well as other university resources. An obvious option is for Allison to email Dr. Fellows to ask for a more detailed explanation of this decision. However, after all that transpired, Allison may feel uncomfortable with the idea of remaining in a working relationship with Dr. Fellows even if it means losing out on the opportunity to work on the grant. Further reflection may bring Allison to conclude that although she no longer wants to have any working relationship with Dr. Fellows, research collaborations are long and slow. Severing ties may have professional consequences, such as loss of publication opportunities and access to helpful professional networks. Allison may choose to gather information from other graduate students, which could also begin to identify additional stakeholders in the situation (Figure 1, Stage 3). In cases of sexual harassment (whether quid pro quo or hostile work environment), there may be a pattern to Dr. Fellows’ behavior such that other students may have been harassed or may be harassed in the future if the behavior is not addressed.Footnote 2

In terms of alternative actions (Figure 1, Stage 4), Allison may choose to continue working with Dr. Fellows or, alternatively, there may be other professors in the department that she could work with. She is on friendly terms with Dr. Marx, who also has a lab in the department. Allison may take time to consider what could happen if she mentions the incident with Dr. Fellows to Dr. Marx or anyone else if she does decide to leave the lab. Potential actions she considers might be influenced by fear of retaliation. Such concerns make comparing and weighing the alternatives especially difficult (Figure 1, Stage 5). Considering other stakeholders involved, such as other potential victims, may increase pressure Allison feels about her decision. Any of her alternative actions relate to not only her well-being but also the other potential stakeholders. If she says nothing, she may not learn the extent to which others have been or will be affected.

Given the complexity of this situation, it is difficult to say which actions would be most effective for Allison and other involved stakeholders. In the wake of the #MeToo era, such situations are gaining awareness in terms of the frequency with which they occur and the harmful effects they can have on health, well-being, and professional careers. Allison’s choice of how to implement a decision and monitor it (Figure 1, Stage 6) is challenging. Given what occurred, Allison might identify a way to report the inappropriate behavior. She could also identify a new mentor to collaborate with while simultaneously working to retain authorship for past work with Dr. Fellows so as not to be punished unfairly. Allison is a true victim in this situation, as reporting a sexual harassment claim comes with both the personal costs of having to revisit unpleasant memories and simultaneously chartering a new career path.

Future directions and conclusion

In this article, we have presented a framework for ethical decision making that is applicable across a myriad of contexts in which I-O psychologists operate. Perhaps the most important step in the framework is recognizing that an ethical dilemma exists, which requires routine reflection on our professional decision making that goes well beyond technical or business knowledge and experience. Moreover, the most difficult decisions we face are those that have multiple “right” answers or only “wrong” answers from which to choose, so having a systematic strategy for thinking through those decisions can help ensure the ultimate decision is well considered and can be executed fairly and with confidence, if not with ease. We hope that this framework will serve as a useful tool for academics and practitioners regardless of career stage.

The best ethical leaders within our profession are those that are capable and succeed at operating in gray spaces where there are not clearly defined or optimal choices. Ethical decision making should be viewed in the same way you would view building a skill, habit, or new muscle, where growth and improvement in ethical decision making occurs over time with practice and experience. Similar to any skill, we must regularly maintain and refresh this skill with practice and exposure to new experiences. It is important to note that there are some situations in which there is not a “good” choice to be made and the best you can do is minimize the effects of the negative outcomes that will be experienced by stakeholders. Using the decision-making model will ensure that focus is given to maintaining ethical standards in your work while considering potential implications of any number of decisions you might make.

The goal of the current work is to spark discussion within the I-O community about ethical decision making and education. Ultimately, we encourage commentaries that critique or expand the framework presented in this article. In other words, commentaries that seek to critique the ethical decision-making framework with the goal of strengthening how it is presented or executed. For instance, commentaries might discuss some of the following issues: What are the best ways to avoid overlooking ethical issues or stakeholders? What is the role of time? What are the best ways to compare and weigh alternatives across the APA principles and standards? What happens beyond initial implementation of ethical decisions? Alternatively, one may also offer additional insights into issues such as the influence of organizational politics in ethical decision making and the social responsibilities of I-O psychologists in an ever-evolving environment. Together as an I-O community, we believe this conversation can serve to improve ethical decisions across the contexts in which I-O psychologists operate and, in the long run, help sustain and protect the reputation and integrity of our field.