Introduction

Public history in Africa has significant potential to illuminate the history of place through community involvement.Footnote 1 This essay explores the possibilities of situating history through the Usambara Knowledge Project (hereafter UKP), whose overarching purpose is to document local environmental history of Tanzania’s Usambara Mountains.Footnote 2 The project’s current goal is to create a digital archive of the oral history and photography. A set of landscapes photographed early in the twentieth century by a professionally trained photographer named Walther Dobbertin serves as a starting point for community discussion and repeat photography. The archive’s openly available digitized material will serve as an essential complement to the paper holdings on East Africa’s highland history in institutional collections. In addition to data collection and dissemination, the UKP encourages community participation in knowledge creation as the archive becomes part of the locality.

This paper highlights the process of developing this community-based history project from far-flung bases in Tanzania and the United States, then documents the efforts of the UKP team to date. So far, we have discovered no shortage of interest from the elder (70s and older) men and women in mountain towns and hamlets.Footnote 3 Our preliminary oral history collection from the summer of 2019 suggests a rich store knowledge regarding the ways in which ancestors of the current population managed the mountain landscape. Elder testimony has also pointed us toward interesting possibilities for future research beyond the Dobbertin images. At this juncture, the UKP team’s progress suggests that through close collaboration local knowledge can be preserved and disseminated.

Project Outline

The foundational piece of the UKP archive is a set of German colonial-era (c. 1910) landscape images taken by Walther Dobbertin, a professional photographer based in German East Africa from about 1900. The German National Archives hold Dobbertin’s originals at Koblenz. Using the high-resolution scans generously provided by the Germans, I began to repeat the photographs in 2016.Footnote 4 We also used the images to encourage discussion during the formal oral history sessions that my team and I began to carry out during the summer of 2019. At times, the conversations revolved around specifics in the imagery. In many sessions, however, the images reminded informants of stories outside of the camera lens’ reach. What I heard and experienced offered a powerful counterpoint to the cultural distance, ethnocentrism, and racism of the colonial archives.

The UKP emphasizes local history. The Dobbertin photographs I have chosen along with the repeat images invite analyses of localities as historically meaningful places. Dobbertin photographed such sites – mission stations, colonial estates, village sites, mountain valleys – that people still recognize as important. The photographic element also invites contributions to the archive of additional locally produced landscape images and accompanying stories that our team will have undoubtedly missed. The UKP image and story archive, we hope, will animate landscape change in a way that the mountain of paper on the Usambara Mountains held in physical archives in distant cities – such as Dar es Salaam, Oxford, London, Wuppertal, and Potsdam – cannot.Footnote 5

In the near term, the public history project, a collaborative effort between the Usambara Elders Council, the Utah State University history department, and the university’s library’s Special Collections and Archives unit, will serve as a basis for a digital exhibit drawing on photographs and oral histories. In addition, our team is currently building a companion physical exhibit focusing on the Usambara Mountains’ environmental history. The exhibit will be portable and ready for shipping in early 2021. Once the exhibits and archive reach the public realm, we hope to sustain its growth according to local community wishes and, of course, the limitations of funding. One of the key challenges over the longer term of the project will be to determine how to store and share material in a digital format that favors access in rural areas with limited digital infrastructure.Footnote 6

Context

Philosophically, the UKP is a child of the humanities disciplines of digital history, environmental history, and public history.Footnote 7 In terms of the knowledge they produce, all three fields emphasize broad audience engagement within and beyond the boundaries of scholarly study. Significantly, the public-environmental history linkage this project advocates developed out of long-standing concerns on the part of both fields over the Earth’s health and a powerful desire to disburse a useful environmental history beyond the academy.Footnote 8 The UKP therefore attempts to reach audiences largely ignored by most academic historians and the paper archives they consult to write history. Place, as a site of knowledge and landscape production, constitutes the archive.Footnote 9

In its focus on landscape, the UKP draws on the scholarly discussion about the meaning of place, locale, landscape, and other spatially derived terminology that blurs the disciplinary boundary lines that traditionally separate history, geography, anthropology, memory, art, and much more.Footnote 10 We aim to apply that broad thinking about a landscape’s makeup to understand how the vital emotional and cultural ties people create with specific places shape the ecological processes vital to land management.Footnote 11 In rural eastern Africa, landscape is still something that people create and alter through their daily activities. People know places because they move through them on foot and work their soils with hand tools. They know places by meaningful names bestowed on them by past generations. And their ancestors remain nearby, interred at home and within reach.

Africa’s mountains and mountain people have drawn much scholarly attention from environmental historians.Footnote 12 Unfortunately, that work’s audience is limited largely to academics and graduate students. As digitized public history, the UKP’s history of landscape health hopes to reach a much larger audience while it serves the local public interest with historical knowledge applicable to sustaining-restoring-maintaining a locale’s ecological viability.

In a sense, the UKP archive is the place itself rather than a controlled building housing carefully indexed boxes of paper. Reading in the institutional archives is tidy and predictable. In the British National Archives, I was given a pager that beeped when my files had been delivered by elevator and conveyor belt. Places, by contrast, are messy, their pasts layered over with vegetation, washed away by floods, and buried in memories. For outsiders, landscape residues can defy recognition. The UKP therefore invites crowd-sourced histories written in multiple languages by local authors.

Being There

In Dispatches from Dystopia, Kate Brown argues that a historian’s analysis is a function of just where they stand literally.Footnote 13 In a series of poignant essays about her research in Ukraine, Kazakstan, Seattle, and Illinois, Brown hammers home the idea that places have memories, which she discovers in her interlocuters’ stories about their health, their movements, their suffering, and their identity. But Brown, an American, is a decided outsider in this place, despite her extended visits in the dystopias and her obvious fluency in Russian and Ukrainian. She struggles with loneliness and the roughness of travel in the former Soviet Union. On her quests of discovery, Brown misses things or makes bad choices. Yet, she is there, in a foreign place, trying to understand something that may be beyond her immediate grasp.

I find similarities in my own journeys through eastern Africa, where I too struggle to interpret the signs of the past. From 1981 to 1983, I was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Narok, Kenya, where I taught high school history and English at Narok High, a boarding school with around 600 male and female students. The school, 2 miles up the road from Narok town, occupies several acres on the lower slopes of the Mau Escarpment, a section of the Great Rift Valley raised to over 9,000 feet elevation by the plate tectonic action. Narok, at 6,000 feet, receives on average about 30 inches of rainfall annually. Most of that falls between March and May. However, rainfall amounts can vary widely from season to season; some years, as in 1983 and 1984, the rains failed almost completely. Narok’s weather, in general, is bleak: it is either hot, windy, and dusty – or cold, windy, and dusty.

I adapted to the setting and came to call Narok High School home. As a history teacher, I taught East African history from textbooks to prepare students for national examinations. We did not read about Narok. Still, I managed to figure out that the British colonial government had set up Narok town as an administrative center in order to control the Masai pastoralist population and their herds of cattle, sheep, and goats. As such, Narok, like many towns in Kenya, had been a node of colonial control populated by foreigners. Beyond the town, pastoralists still inhabited dispersed settlements and moved their animals regularly according to seasonal needs. I saw that Masai adherence to pastoralism and their rejection of Western clothing and education fostered stereotyping. Townspeople spoke about Maasai as lazy, dirty, backward, and uncivilized. People made jokes about them and refused to ride with Masai on public transportation to Nairobi. To make matters worse, Masai lands were under attack. In northern Narok, local government officials and well-connected local businessmen secured government loans to finance fully mechanized wheat farms on the Mau highlands’ pastures and forests. In southern Narok District, the Kenyan government had cordoned off pastures for the paradoxically named Masai Mara National Park. Witnessing this land grabbing, discrimination, and inequality awakened me intellectually in a way that reading history monographs as a college student had not.Footnote 14 Years later, as a graduate student, I had the opportunity to study more systematically as a historian land disputes in eastern Africa. In the event, I ended up over the border in northern Tanzania’s Usambara Mountains for a year of doctoral work on the region’s environmental history beginning in the summer of 1991.

Before reaching the mountains, I dutifully read for several weeks in Oxford’s Rhodes House Library and the Tanzania National Archives in Dar es Salaam. After that, I lived in the mountains for seven months recording oral histories with the help of two assistants, Mr. Sufian Shekoloa from the Mlalo Basin, an agricultural region on the massif’s northern side, and Mr. Peter Mlimahadala, whose family hailed from the herding regions of the central massif. Their language skills proved invaluable to every session. Although I spoke Kiswahili adequately, we decided to record testimony in one of three local languages (Kishambaa, Kipare, and Kimbugu) with the assistants translating into Kiswahili for me. Mlimahadala, especially, felt strongly about using this system. As it turned out, because informants understood what Mlimahadala or Shekoloa were translating for my benefit, they could and did correct meaning when necessary.

In addition to his fluency in all three of the local languages (five in all), Mlimahadala brought other vital skills to the table. Fortunately for me, Mlimahadala had learned to type as a boy at the Irente School for the Blind just outside the West Usambara district headquarters of Lushoto. Though he survived a bout with smallpox at the age of nine, the disease had taken his sight. Mlimahadala also translated all of the interviews into Kiswahili as he transcribed them, pounding out the transcripts on a manual typewriter. Perhaps as a result of his blindness, he had an intense curiosity about his surroundings, and he was a bold and engaging interviewer, always probing and pointing out contradictions. As luck would have it, Mlimahadala’s grandfather, also named Mlimahadala, had been a well-loved local chief under the British Mandate, and that name opened many doors for us in the Mbugu and Pare communities.

Mr. Shekoloa’s skill set differed. As an administrator at a secondary school in Mlalo town, he was exceptionally well organized, always on time, and prepared. As a respected community member, whose family had been in the small town of Mlalo for several generations, he simply knew everybody. Finally, Shekolola had the hiking skills of a mountain goat. We often walked for miles (employing numerous “shortcuts”) to places that to him were “nearby.” Like Mlimahadala, Shekoloa found his own interest in the region’s history as our work went on. When he retired four years ago, he opened an office in town and began to encourage his community to build and maintain a historical and cultural museum.

I had no field training as an oral historian and initially saw my potential informants as vessels containing desired information that would fill gaps in the archival record. My role was simply to ask the right questions. Early sessions, not surprisingly, proved overly formal and stilted. Over months of interviewing, Mlimahadala, Shekoloa, and I learned how to follow angles of inquiry depending on our interlocuters’ realms of knowledge.Footnote 15 Our experience led us to seek out men and women with specialized understandings of, say, healing, iron working, irrigation engineering, farming, livestock rearing, education, and ritual, among other things. We also began to learn the oft-recounted stories that coalesced around social stress and landscapes. Having an informant recount one such story made for a great lead-in to questions about the nature of ecological stress.Footnote 16 Our informants taught us to see old, unused structures as check dams and irrigation furrows. In this way, the three of us began to learn to read landscape history.

Stories differed according to site. Logging had dramatically and rapidly altered the montane forests on the massif’s central plateaus and western flank. Here, we found the ghost landscapes lined with diseased cypress trees, exotic replacements for the biologically indigenous cedars and podocarpus forests logged by a succession of timber concessions. People from these parts who participated in the process told the stories of losing environmental control.

Subsequent trips to the field in 1996 and 1998 were not the same. I had far less time. By then, Mlimahadala lived in Dar es Salaam, and Shekoloa was busy starting a new school in Mlalo. Though Mlimahadala and I held sessions, they lacked the same intensity. People had their minds on funerals as AIDS burned its way through the Tanzanian bodies. I retreated to the institutional archives and the comforts of printed materials filtered and organized by experts who wrote in my mother tongue. In practical terms, my approach to research required reading extensively from the colonial archive while trying to assemble another in the field. The oral field archive differs from the colonial paper in that it is based on a mutual agreement on the value of creating a collaborative record created inside a community. In Usambara, learning the landscape meant foot travel, extended greetings along the pathway, hours of sketchy driving conditions on unpaved roads, condolences for the dead, drinking sweet tea, breaking bread, and listening to stories.

The material that Mlimahadala, Shekoloa, and I assembled appeared in my published work, all of it for scholarly audiences as per the requirements of tenure and promotion. According to my obligations to the Tanzanian government, I sent the published materials to the required institutions in Tanzania. Unfortunately, the published material remained largely inaccessible to my community of informants. If my experience resonated in the formal historical writing, it only emerged in place names and the footnotes identifying my informants’ homes. The experience of being there rarely came through in the prose. Colleagues urged me to find a new place study, and, although I continued to visit the mountains, a new project focused on the Zanzibar Islands.

In a way, both as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Kenya and a foreign researcher in Tanzania, I was an imperialist. The Peace Corps’ association with the US government’s strategic and economic interests speaks for itself. However, my own research and writing had similarly benefitted my own career rather than the many informants who shared their time and insights with me; academia encourages such an approach. A more equitable course of study, a public history, would situate knowledge of a place’s past among its inhabitants.

Practicing Public History: the UKP

Public history gets a bad rap among academic historians. Several years ago, our history department began discussions about hiring a public historian to join the faculty. Predictably, some colleagues argued that teaching public history, and especially doing public history, was not part of our departmental mission. The subtext was we as academic historians did something more rigorous. We eventually hired a public historian and now offer graduate and undergraduate courses in the field. Colleagues have now supervised undergraduate and graduate research that culminates in digital exhibits for a variety of audiences outside academia. Our public history students have landed private and public sector jobs. Despite the successes, our new departmental guidelines for tenure and promotion identify the single-authored monograph as the “gold standard” for excellence in research for promotion to associate and full professor. Public history and its corollary, digital history, receive only minor mention at the end of the list of acceptable research and writing. Going public has its risks.

The public history envisaged under the UKP rejects narrow academic interpretation. The UKP encourages exhibits that provide insight into daily life, sustainable agriculture, introduced species, natural disaster, famine, colonialism, and changing ecosystems. The knowledge should complement the growing scientific knowledge of East Africa’s natural history with the sense of place expressed by community members.Footnote 17 The approach draws its impetus from the National Council on Public History and the American Society for Environmental History to highlight a decades-old collaboration.Footnote 18

Local community support serves as the UKP cornerstone. In this case, our team began in the spring of 2019 to consult closely with the Mlalo Elders’ Council through Mr. Shekoloa. After the summer 2019 oral history sessions, we decided to house a portable physical exhibit at Mlalo under their care. This past autumn, team members Mr. Kitojo and Mr. Shekoloa (as a representative from the Mlalo Council) attended the annual meeting of the Usambara Mountains Elders’ Councils (including Lushoto and Bumbuli Districts, which cover the West Usambara Mountains). Mr. Shekoloa laid out our work from the previous summer and our future plans for the exhibits. Both men were moved by the Council’s heartfelt support for the UKP. With the help of these local institutions, the team can now make use of the connective bonds of the elder community across the Usambara Mountains.Footnote 19

Then and Now: Using the Photography Archive

I saw possibilities for collaborative study when in 2015 I discovered on the Wikimedia Commons hundreds of Dobbertin’s historical images from German East Africa. Not surprisingly, good chunk of the images came from the Usambara Mountains, a German settler region and a relatively easy journey from Dobbertin’s home in the coastal town of Tanga.Footnote 20 The German National Photographic Archive in Koblenz purchased Dobbertin’s original glass negatives (9×13cm) and makes medium resolution (4 to 7 megabytes) scans available to the public for a reasonable permission fee. The size of the negative plates makes for a very large print. Moreover, the nature of the lens and camera Dobbertin used in the early 1900s creates a very pronounced depth of field and therefore incredible sharpness across the landscape, even in the digital scans. His images are well-composed, and I discovered later that two sets of the photographs make up landscape panoramas centered on mission stations at the towns of Mlalo and Bumbuli. Such clearly recognizable and important historical places begged for contextualization through an infusion of local knowledge and oral history. Moreover, taking the images back to the mountains, so to speak, allowed me to return what Dobbertin had appropriated without permission in the photographs. During the fall of 2015 and the summer of 2016, I returned to the mountains to see if these photographs still had mnemonic value, carrying with me numerous photocopies of Dobbertin’s images.

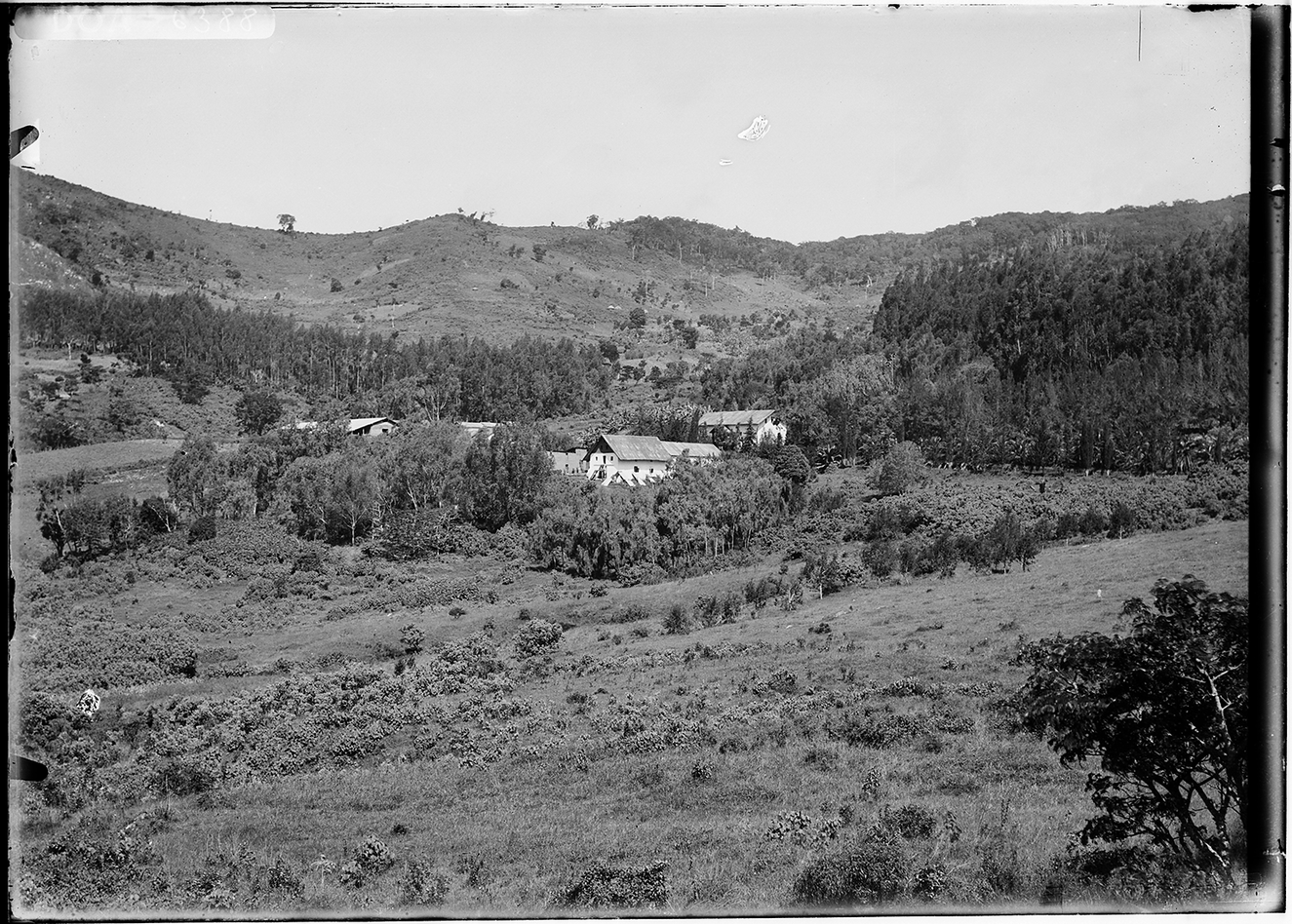

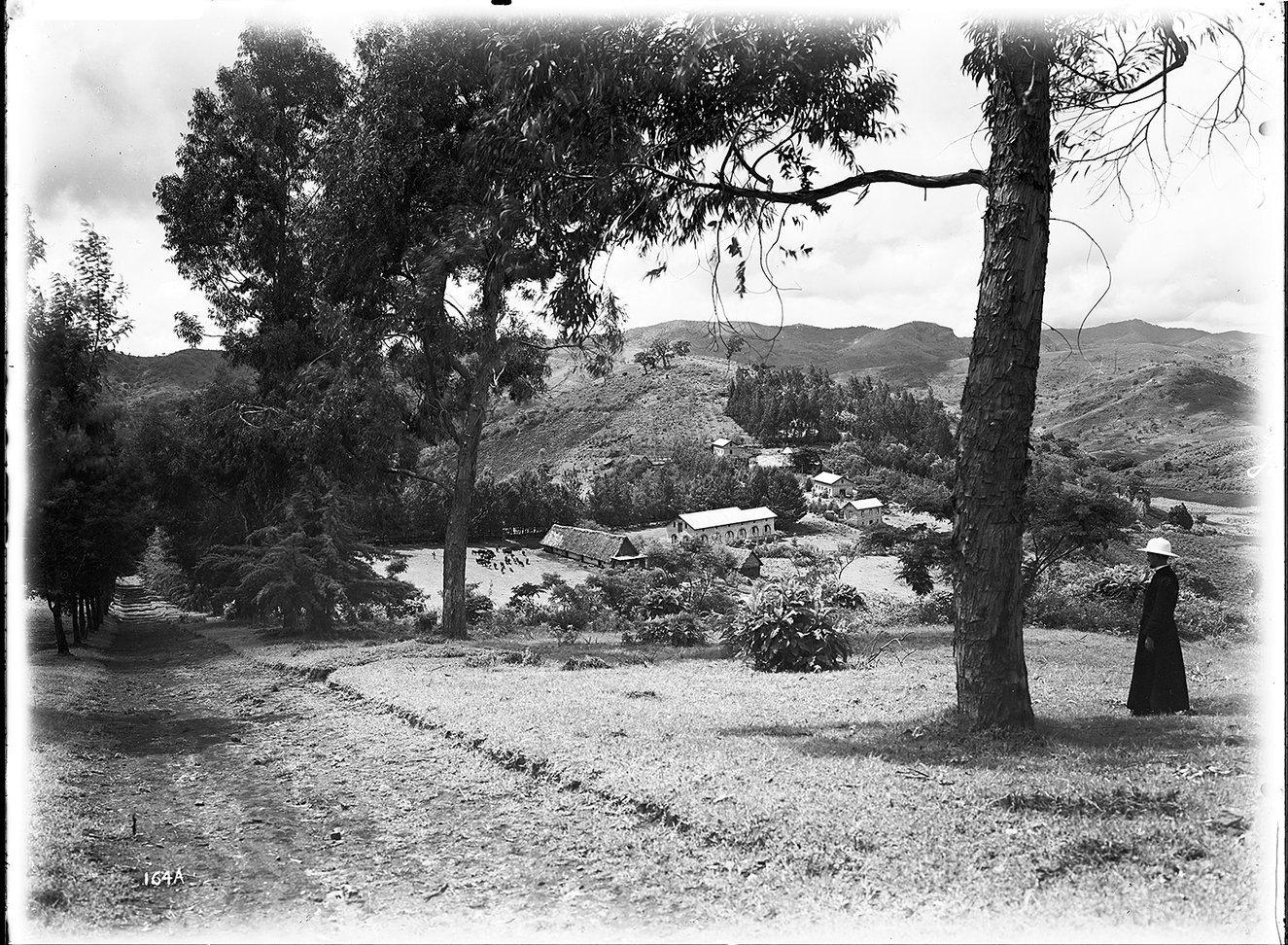

The imagery provides a striking contrast to today’s landscape. For example, around Mlalo town on the northern tier of the West Usambaras, Dobbertin’s panorama reveals extensive and lush banana plantations dot the mountain basin’s very open, rolling landscape. Today, the mountains’ more densely populated hillsides carry far more woody vegetation, especially Eucalyptus and Grevillea trees, fast-growing exotic species that evolved in Australia. The stark difference in vegetation and housing styles speaks to a history of multiple decisions about land’s health, as well as its possibilities and limitations.Footnote 21 The historical images also show dense Eucalyptus plantings, especially on the Kwai Farm (Figure 1), a German experimental institute where the manager nurtured multiple species, and around the German Mission Stations (Figure 2). In fact, they are ubiquitous in most of the images of German settlement as settlers surrounded themselves with these fast-growing imports. Clearly, ideas about the value of trees on the landscape differed significantly between the settler and indigenous communities in the 1910s.

Figure 1. Kwai Farm, West Usambara Mountains, c. 1913. Photograph by Walther Dobbertin. As with Gare Mission, the Kwai experimental farm is covered with exotic tree species. Note the remains of the experimental Eucalyptus grove in the upper right quadrant planted by Emil Eick in the late 1890s. German National Archives index number: Bild105-DOA6388 TIF.

Figure 2. Gare Mission, West Usambara Mountains, c. 1913. Photograph by Walther Dobbertin. At the Trappist monastery, the vegetation is almost entirely exotic, including Eucalyptus in the foreground and lining the roadway leading to the mission complex. German National Archives index number: Bild105-DOA164 TIF.

And yet, these species cover many hillsides in the mountains; farmers now accept them as legitimate additions to their farms. In Ten Million Trees Later, Lars Johansson examines the German project that fostered a massive tree-planting campaign in the 1980s and 1990s.Footnote 22 Johansson worked in the early 1980s as a Swedish volunteer for the German government’s regional integrated development project, which emphasized soil, water, and forest conservation. Twenty years later, Johannson wrote a careful and informed retrospective that rejects as simplistic clear-cut judgements of success and failure. He disaggregates for a general audience how men and women selectively altered land use, residence, labor, livestock keeping, tree cutting, and tree planting based on all of the possibilities in front of them. By the late 1990s, the German mountain restoration projects had abandoned erosion control initiatives in favor of a laser focus on tree planting across steep hillsides. Finally, in 1999, the German government’s Gesellschaft für technische Zusamenarbeitung (GTZ) claimed success and finally walked away from northeastern Tanzania after thirty years, leaving behind the Grevillea and Eucalyptus as reminders.

Johannson empathizes with the farmers; his photographs of them and their mountain homes are stunning and humane. He also recognizes the irony of German project managers promoting many of the same locally reviled “modernization” measures as their colonial predecessors, such as livestock genetic improvement and stall feeding, bench terrace construction, the planting of grass lines along contours to hold soil in place, and prohibitions against field preparation with fire. Johannson’s landscape photography eloquently tells a story of selective tree planting and adoption of project ideas based on local applicability. As Johannson pointed out in 1999, trees are everywhere. In addition to the Australian imports, citrus, mango, coffee, and avocado trees now grow in many farming zones. All of them are valuable.

In the case of the UKP, repeat photography captures the proliferation of trees in the spots that Dobbertin used for his originals. Finding the original locations of almost all of the originals was not terribly difficult, although a few of the images stumped all of us until very recently. Also, many of the German structures remain intact, including mission stations at three of the locations. The mountain ridgelines likewise help locate the horizon on several photographs. Nonetheless, the presence of thousands of maturing trees blocked the original view at several sites, as in Figure 3 at Gare. A drone with a good camera would help get above the obstructionist Eucalypts and Grevilleas.

Figure 3. Gare Mission, 2016 (compare with Figure 2). A far less open landscape greets today’s visitor. On the hillside behind the Mission, exotics like Eucalyptus, Grevillea, Norfolk Pine, and Jacaranda, to name a few, have grown into a forest that serves as a site for festivals and pilgrimages. In the foreground, farmers have now established shambas on a section of the former mission property where they have planted small gardens of banana and avocado.

Taking repeat photographs in local settings draws attention. On several occasions, concerned citizens approached us to ask for an explanation of our tromping around their neighborhoods. From our conversations, it seemed to me that some people perceived us as the equivalent of land surveyors. And, in a very real sense, the camera took measurements, an act that has historically raised suspicion in the mountains. We even drew small crowds at Mlalo, a fairly cosmopolitan town. In order to temper the spectacle, we took time to show people the Dobbertin views and to explain our intentions at great length. This calmed people, even piqued their interest, and sometimes netted us new contacts.

During the 2016 sojourn, Kiva, Shekoloa, and I began to arrange informal interviews with elders in the vicinity of the photography locations. Some of our efforts met with stiff resistance. We noted, for example, a very negative response at a place called Kwai when we arrived to take some photographs. Only after much discussion could we convince the local farmers who met us that we were not there to confiscate or survey the valley land for sale. Eventually, they helped to arrange a discussion with three area men who told us very powerful stories of grievance based on their reading of German experimental station photographs. The team felt that stories like these and the striking landscapes in the photographs needed to be available to anybody who wished to hear or see them. The ties to place in our informal discussions could not have been clearer to us. The photographs stirred a range of emotion, memory, and story. Based on our preliminary work, Kiva, Shekoloa, and I agreed to go forward with the UKP.Footnote 23

Oral History Archive

The oral history conducted under the project aims first and foremost to document environmental history in a locale where most people still depend on access to land for their living. Small-scale farmers across Tanzania have managed a changing climate, an increasing population, and externally-driven development initiatives for decades. To the UKP, they work as consultants bearing indigenous knowledge rather than aid recipients.Footnote 24 The indigenous knowledge stores also aid historians who seek to understand how, after nine decades worth of dire agroecological forecasts from outsiders and a succession of development project “failures,” farmers weekly export truckloads of carrots, cabbages, potatoes, tomatoes, avocados, cucumbers, peppers, and onions to coastal cities.Footnote 25

In July of 2019, we began the formal oral history phase of the project. A few months prior to my arrival, I asked Mr. Kitojo to go to Mlalo in order to meet with Shekoloa and the Mlalo Elders Council.Footnote 26 They floated ideas and identified men and women who would know the region’s landscape history. Mr. Kitojo reported that their discussion went on for two days. In the end, the council advocated strongly for a local museum of culture. They also wrote a formal letter of support for the UKP. Mr. Kitojo also traveled by motorcycle to the more remote sites with copies of the Dobbertin images in hand. He was able to find both men and women willing to talk with us about the prints. By the time I arrived, Mr. Kitojo and Mr. Shekoloa had organized and scheduled almost all our sessions. We conducted more than twenty interviews at Mlalo during three group sessions. We also made day trips to several more sites of Dobbertin’s landscapes.Footnote 27

Each formal session differed, depending on the number of informants in any session, age, and gender. Our informants were mostly in their seventies, eighties, or nineties. At Mlalo, we received such an enthusiastic response that at times the Mlalo Elders’ Council meeting room hall held seven or eight informants, along with numerous visitors politely listening in. We interviewed mostly men at the Mlalo sessions, a limitation that the team identified and will rectify as we put out calls for informants. Sessions at locales other than Mlalo town were usually one-on-one or had two to three interviewees. Venues differed, sometimes we talked in the meeting rooms of local government offices or we met in our informants’ homes. We quickly learned that, in some cases, informant eyesight did not allow them to actually view an image with any accuracy. Others donned their reading glasses and thoughtfully pored over the details that Dobbertin had given us. We asked about structures, landforms, locations, the organization of space, and the wazee (elders) accommodated us with the best of their knowledge. Our discussions yielded insights that we did not anticipate. At Mlalo, for example, elders marveled at the amount of water in the Umba river in Figure 4, Dobbertin’s photo of the Mlalo Kaya (that is the Kiswahili word that the elders used to describe an area’s ancestral center) in what would have been a dry season. What I saw simply as a feature that Dobbertin used to compose the image was on their minds because at that moment the river carried only a trickle of water. As we tried to keep our conversations focused on the image details, our informants told us stories that spoke to the image’s vibe – a Lutheran missionary cheating a boy out of a day’s pay, a road survey undermined by magic, a beating, a drought, a ruling clan’s impotency, or a worry over the future.

Figure 4. Mlalo Kaya, West Usambara Mountains, c. 1913. Photograph by Walther Dobbertin. This is the ancestral center of the Mlalo chieftaincy. The differing architectural styles suggest that devotees of Islam lived in the old town. German National Archives index number: Bild105-DOA269.

At the moment, Mr. Kitojo is culling stories from the audio files for two exhibits (physical and digital). Since the elders almost always mixed Kiswahili and Kishambaa, the team is discussing dubbing in Kiswahili and in English. We will try as well to integrate audio and some repeat imagery into the Dobbertin landscapes, which will serve as centerpieces. Using readily available materials and technologies, we will build the physical exhibit to be portable enough to fit into large duffle bags. On the digital side, student interns and the university library’s Office of Digital Initiatives have been working together to develop context and design for the digital exhibit, which will allow us to exhibit far more material. The Utah State University Special Collections and Archives (SCA) will host the digital exhibit and archival materials. Library server space will allow us to add additional audio files, images, film, and more context as we collect it.

Expanding the Archive

One of our oral history sessions pointed us in a new direction. As it happens, Dobbertin took several images of the Vuga Lutheran Mission station. The photographs depict an open place with a few small-scale banana gardens on the hills above the station circa 1910. In July of 2019, Mr. Kitojo arranged for us to talk to Mzee Yambazi, a man in his eighties who had grown up nearby. We found him at his house a couple of miles or so from the mission station. We spoke for a couple of hours about Mzee Yambazi’s many years as a teacher at various schools around the Usambaras. He had retired to his family’s farm, but worried that his children, professionals scattered across eastern Africa, had no interest in maintaining the farm. After tea, we gathered our things and started toward our vehicle. Almost as an afterthought, Mzee Yambazi asked us if we wanted to see the shamba (farm or garden); we agreed, of course. I felt particularly stupid; Mzee’s farm wasn’t part of the image, so I had not even given it a thought.

Figure 5. Mzee Yambazi’s Agroforest. Dracaena mark a recent grave site. Photo by author, 2019.

From the Google Earth view, Mzee’s seven acres are largely covered by tree canopy anchored by a couple of large Albizia trees, whose leaf fall fixes soil nitrogen, along with fruit trees of various types. Looking from the ground up, one sees a tree canopy covered by a huge netting of lianas that will yield the kwema nut.Footnote 28 Underneath this canopy, Mzee cultivates bananas of several types, along with yams, beans, and medicinal plants. Mzee had left some acreage unshaded and in 2019 planted a crop of maize on the open gentle slopes facing the plains to the south. Mzee Yambazi inherited the shamba from his ancestors, who are interred in a sacred space within it, the graves surrounded by dracaena plants, as in Figure 5. In the complex botanical collection of useful forest trees, banana plants, shade-loving legumes, and tubers, we immediately recognized a strong resemblance to the sustainable farming systems in Dobbertin’s 1910 photographs, taken more than a century ago. From the edge of Mzee Yambazi’s land, we could see a few other similarly situated agroforests. As if to attest to the antiquity of agriculture in this place, an ancient and still-functioning irrigation furrow across the valley followed a centuries-old pathway along the hill contours, dropping gradually toward the plains in the distance.Footnote 29

Yambazi’s agroforest recalled one of our sessions at Mlalo, when one informant eloquently described the beauty and utility of the agroforestry system that they saw in Dobbertin’s photographs. He explained in detail the ecological principles behind the particular version of agroforestry in the image, even though, during his life, most people had stopped farming in this way. The continuities of the testimony and the image with what we saw at Mzee Yambazi’s farm struck us as vitally important. We began to see agroforests as places where culture, image and story meet, and we intend to make the landscape feature a research focus. If funding allows, we will film the agroforest sessions. Along these lines, our project needs to hire a professional photographer-filmmaker. My skills are simply too rudimentary to capture in a digital image the kind of detail that Dobbertin did with glass and chemicals. An image with equivalent depth of field requires the photographer to overlap dozens of images and then knit them together with a computer application. We have an expert landscape photographer willing to work with us, but as yet, no funds to pay him. Our photographer would, among other assignments, repeat all of the images the project has obtained from the German National Archives.

Of the Dobbertin images we have yet to repeat, Bumbuli, a town on the southeastern side of the mountains, is the most important. Dobbertin created an exquisite panorama there that includes the founding town settlement, complete with traditional housing arrangements intact. The site certainly recalls the setting of the Mlalo Kaya. Bumbuli is a very important historical place, and the images and accompanying oral history would interest a large sector of the people on the mountains’ southeastern tier.

Conclusion

Setting up a community-based project as a foreign scholar requires experience, foreign language skills, dedicated collaborators, and persistence. To date, the Dobbertin images have helped to bring together those essential elements. From my time in the mountains, I already knew the places in the landscape images, at least most of them. Despite the enthusiasm and community support the team has enjoyed so far, the UKP’s success ultimately depends on financial support and the development of closer ties between the participating institutions in the United States and Tanzania. And we must deal with unanticipated challenges.

An October 2019 flash flood washed away the Mlalo Elders’ Council headquarters along with many other town buildings along the Umba River. According to Mr. Kitojo, it rained heavily in the northwestern Usambara Mountains without letup for almost 24 hours. The Council office contained several rather large tables, a desk, a cabinet, and several chairs. Luckily, the wall of water took the riverbank and building early in the morning while people slept. No one was injured. The beginnings of our archive – several large paper copies of the Dobbertin landscape photographs of the old town, the nearby Lutheran Mission station, and the surrounding valleys, along with some book donations – are now buried in the sediments of the river valley. We can replace all of those things, but Mr. Shekoloa’s death a few weeks later seemed to me a tragedy of far larger proportion. He brought to the project tremendous energy and presence. Shekoloa had brought us all together in the council hall. He respected the process and kept us on schedule and well fed. He continually identified new informants willing to collaborate. For these contributions and so much more, he will be missed. Despite the double tragedy, the Mlalo’s Elders’ Council continues to send me greetings and inquiries urging on the project.