Introduction

At University of Zimbabwe, the Department of Economic History (DEH) was birthed in 1988 with scholars such as Dr. Joseph P. Mtisi, Prof. A. Mlambo, Dr. E. Pangeti, and Dr. V. E. M. Machingaidze being among some of the first lecturers. The Department emerged as an offshoot of the Department of History, with the latter having been established in 1957.Footnote 1 Until 2020, when the DEH was dissolved, the University of Zimbabwe was the only institution (out of 17 universities in Zimbabwe) that offered economic history (EH) at the tertiary level and with a specific department dedicated to the discipline. Even on the continent, while economic history modules were taught in African universities by 2020, the DEH at the University of Zimbabwe was arguably the only functional stand-alone department in Africa dedicated to the training of economic historians. This paper attempts to chronicle the rise and fall of the DEH and, perhaps by extension, of the discipline of economic history.

The manner in which the Economic History Department emerged is very critical and, perhaps, can be considered to have contributed to its downfall. It seems that over time, economic history as a discipline in Zimbabwe failed to significantly distinguish itself from history, which was also offered at the University of Zimbabwe. For example, the methodologies and the content remained largely similar on some occasions. Also, undergraduate courses in the two programs employed a similar format, which was a regional approach to the teaching of the discipline. This was apparent where, for example, history students would take History of West Africa or Southern Africa as a module, and those in the DEH would take a similar course named Economic History of West Africa or Southern Africa. Consequently, from first year to their final year, students from these two departments or programs would “scramble” for the same textbooks.Footnote 2 This continuously haunted the DEH, and, in the corridors of power or even amongst ordinary folks, one always had to justify distinguishing the two disciplines. I would also argue that the EH Department’s problems of survival also emanated from the proximity that EH continued to have with history.

However, from 2017, there was a deliberate effort to further develop economic history as a distinct discipline. The university went through a massive curriculum review, which the department took advantage of. Effort was made to rebrand the discipline not just as an academic but also as a professional program that needed to speak to and contribute towards the country’s economic experience. To achieve this objective, an industrial component, among other things, was introduced to the discipline, which now extended to an additional year (to make 4 in total) for undergraduates, with the third year dedicated to industrial experience. In 2020, before anyone could even evaluate the efficacy of the new curriculum introduced in 2018, another curriculum review was instigated by the university administration under the guidance of what was dubbed Education 5.0. Education 5.0 was touted as an improvement of Education 3.0, which emphasized teaching, research, and community service as the mandate of universities in the country. Education 5.0 added industrialization and innovation. Education 5.0 was not open for debate or discussion. Academics were not allowed to question how, for example, industrialization and innovation were not already integral to the existing Education 3.0. Departments were frog-marched into top-down curriculum reviews with some disciplines and departments being dissolved or reconfigured altogether.Footnote 3 In this context of radical curriculum changes, the Department of Economic History was merged (or perhaps dissolved) with the History Department to establish a new Department of History Heritage and Knowledge Systems. As the curriculum radically changed, new names were minted for the old programs that had been taught in the DEH.

Perhaps one would argue that the Economic History Department missed an opportunity to radically reform and distinguish itself when it remained avowedly qualitative and closely related to history in terms of content and approach. Indeed, when I took my first year as a History, Archaeology, and Economic History major in 2001, there was a lot of overlap in courses such as the introductory and regional courses from economic history and history. And yet elsewhere, economic history had been experiencing a huge methodological shift where greater emphasis was now being placed on statistical methods.Footnote 4 At the University of Zimbabwe, we missed on this cliometrics revolution. We may never know for sure if adopting cliometrics would have prepared the discipline for the 21st-century onslaughts. There had been attempts to have students of economic history take courses from the economics discipline and vice versa, but by 2001, when I was an undergraduate, this only existed on paper. In fact, the two departments operated like two separate islands without any close cooperation.

I joined the DEH in 2001 under the advice of Munyaradzi Munochiveyi, now a renowned academic. Munochiveyi immediately assumed the role of a big brother and mentored me. He was already quite advanced then in his studies, as he had finished his undergraduate studies and was then a Graduate Teaching Assistant in the DEH. Before Munochiveyi, I had never heard of the discipline of economic history. This is an important point that reflects on the obscurity of the discipline. This obscurity has haunted the discipline since its inception. Until recently, economic history was not quite known in the country. There are few who know of its existence and even then, these few wonder what it is and how different it is from mainstream history. When I joined the department as an undergraduate, I was very clear about what I wanted to do. I wanted to be an economic historian, but little did I know that I would come to head the department at some point in my career. The story of the DEH is in many ways, therefore, woven with my story as student (2001–2004), as a Graduate Teaching Assistant (2006–2007), as a Lecturer (August 2009 to 6 April 2021) and, finally, as chairperson of the department (December 2016 to August 2020).

The Rise of Economic History Department: A False Start?

The DEH began as a unit in the Department of History offering an Honors in Economic History and Masters in African Economic History. Its first crop of honors students as a unit was in 1985 with seventeen students, six of whom had first-class pass marks.Footnote 5 Efforts to expand the unit into a department can be traced back to early 1980s, but these were met with resistance from fellow colleagues in the Department of History. After protracted negotiations and tensions, the DEH was eventually established in 1988 as part of the Faculty of Arts. The Department offered five main programs, a BA (straight) Honors in Economic History (three years), a BA Special Honors in Economic History, a “taught” Master of Arts in African Economic History, an MPhil in African Economic History, and a PhD in African Economic History. Economic history was also taught as one of the three majors required in the Faculty of Arts for BA General in the first year. In the third year, a student would drop any one of these majors. A BA “straight” honors degree was by merit. Students who would have performed well in their first year economic history courses were invited to specialize in the discipline for the remaining two years at the university. Normally, these would be less than ten students, going to as low as five. In my own stream, initially five were invited; two more joined after making a case to the Chairperson, and, ultimately, there were seven of us in total. The other students would continue with EH as part of their BA General studies, and a number would eventually drop this at the third year when they were required to only proceed with two of their three majors. I would argue that these arrangements had very critical implications for the discipline of EH. The few who continued with economic history graduated and would usually join the teaching field where they became history teachers.

Teaching economic history as part of BA modules diluted the discipline and reduced its impact. Here was a discipline which had the potential to compete with economics or even take the limelight, as later did its sister program, development studies. Both development studies and economics developed as stand-alone disciplines, training professionals in huge numbers while economic history remained overshadowed by BA General Studies and offered an undergraduate honors program that produced few graduates, many of whom went overseas after graduating. I would argue that, at the end of it all, it was a numbers game. The fewer the graduates the DEH produced who specialized in the discipline, the less impact it made in the country, and, ultimately, the less known it became. I would put a conservative estimate that, on the other hand, economics and development studies (initially at Midlands State University) were producing over fifty students a year each while their competitor at UZ, economic history, produced not more than ten students a year. However, because the department had received international recognition for the quality of its students, these ten or fewer students always found themselves absorbed by international institutions. Under such circumstances, the discipline did indeed succeed in making a significant mark on the international frontier as compared to other disciplines.

Notwithstanding these challenges, the DEH enjoyed successes, especially on the international frontier, including hosting a major conference in 1995. The department continued to produce men and women that today have come to make a mark on academic, social, economic, and political spheres, locally and internationally. From 2000, however, the country began to plunge into an economic and political crisis, following the controversial Fast Track Land Reform Program (FTLRP) that year. The crisis reached its peak in 2008 with hyperinflation reaching the second highest in the world for a country at peace.Footnote 6 The university at large and the department in particular were not spared from this crisis, as many lecturers left for greener pastures. The crisis made the environment for research extremely difficult and also isolated academics from the rest of the world as the country cut ties with the international community, particularly the Western world. Learning and teaching was itself extremely difficult under the circumstances, as tuition was extremely expensive and financial resources limited as a result of the economic turmoil.

In midst of these economic challenges, a few of us were able to get some reprieve from the new Graduate Teaching Assistant program. This had been part of the university policy for as long as I remember. Here, the University of Zimbabwe would identify candidates for its MA program who would assist with tutorials and marking assignments while they were exempted from tuition and received a small stipend. Nine of us who were taken in as Graduate Teaching Assistants also enrolled for the MA in African Economic History. As a result of deepening economic challenges and subsequent cuts on expenditures, the Graduate Teaching Assistant program did not last three years after my graduation. Consequently, doing a Master’s program became extremely expensive and virtually impossible. The DEH, like many at the university, failed to enroll students for some time, largely because of the expenses and the volatility of the economy. Thus, these policy shifts had serious implications on the capacities of departments to train future experts in their disciplines.

The year 2009 was a year of hope for the country. The Government of National Unity (GNU) was established, and, for a period, it watered down the growing toxic tensions between the Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front (ZANU PF) and the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), then the biggest opposition party.Footnote 7 I also rejoined the department at that point as a Temporary Fulltime Lecturer, a position that did not have the security of tenure. This is an important point because it affected the capacity of the university to retain staff. I remember that, at some point, about a third of the staff members were without the security of tenure. At one point, the department lost two lecturers at once.

Towards Applied Economic History: The Zenith of Economic History

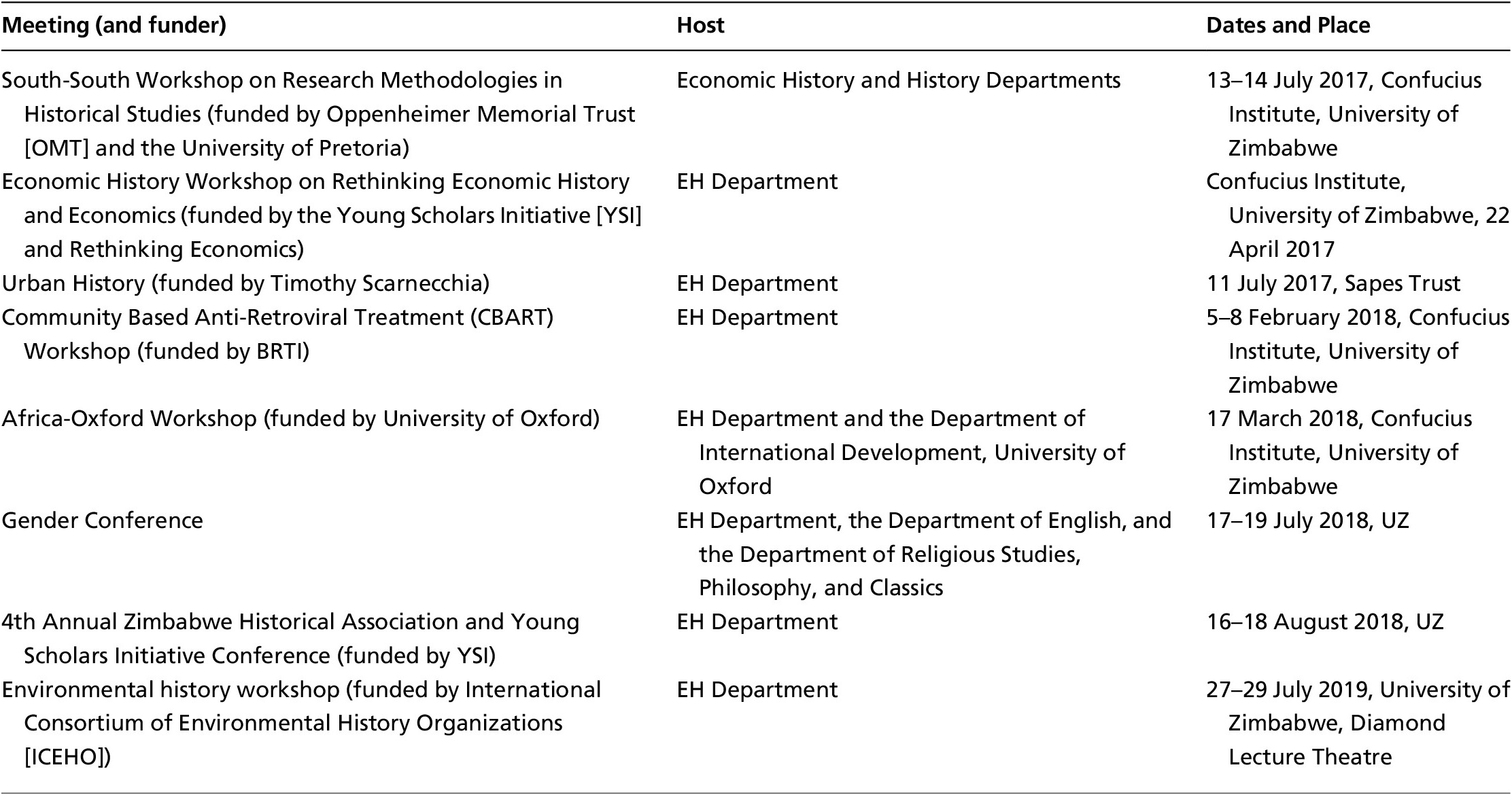

In 2017, the university began a curriculum review that culminated in significant changes to the discipline of economic history. First, BA General Studies was removed. Economic history at UZ became a stand-alone Honors subject taken by students from their first to final year. There were mixed feelings about this development. For example, some lecturers saw the Honors programs as a reserved route for those with academic potential, hence the requirement to do a research dissertation towards completion of the program. Not everyone, it was argued, was cut out to be in academic research and writing. The second development was a review of the curriculum. As a department, we began to move towards professionalizing the discipline. We insisted that a year of industrial attachment be included in the program, which now ran for four years. At the end of the program, we hoped to produce a four-pronged graduand: someone who was an economic analysist/thinker, a development practitioner, a researcher on contemporary social and economic processes, and, finally, a professional historian in the business of historical research, writing, and even documentation and preservation of the past. To achieve these goals, a number of courses were introduced. Table 1 is a sample tabulation of some of the courses that were intended to train an economic thinker, researcher, development practitioner, and historian. I have not included the regional courses from the old program, which still continued to be part of the menu of the new program and which included Economic History of Latin America, Asia, Southern Africa, Europe, and North Africa, among others.

Table 1. A sample of the courses intended for training an economic thinker, researcher, and development practitioner.

The courses moved away from being regional courses to more thematic and quite specific courses. They explicitly spoke to developmental issues and deliberately honed students into professional researchers. The introduction of industrial attachment, as well as thematic courses that spoke very specifically to economic subject matters, was one of the many efforts to rebrand economic history as a distinct discipline that would contribute to the economic situation in the country. Partly as a result of the need to find partners who would also host EH students during attachment, there was a rigorous attempt to market and popularize the discipline locally. Formal and informal synergies were thus nurtured with local institutions.

The period between 2017 and 2020 was arguably the zenith of the Department of Economic History and the discipline at large. As a department, we also took advantage of an ongoing curriculum review within the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education and advocated the extension of the discipline to secondary schools. EH was to be studied from form one to A level (four years of high school plus two additional pre-university prep years). Apparently, this had once been done some years back but the teaching of EH in secondary schools had never been taken up. I was part of the process that came up with the Ordinary Level (high school) and Advanced Level syllabi in EH in 2017. The process was one of tense debates with fellow historians who felt EH wanted undeserved attention. It was argued that economic issues could easily be introduced in the existing history subject without necessarily having to create a stand-alone subject. To this day, many secondary schools resist the teaching of economic history as a subject. There has, however, been an increasing uptake of the subject in secondary schools, with a WhatsApp group being formed and hosting 96 participants at the time of my writing, most of whom are economic history-trained teachers in secondary schools, while others are contemplating introducing the subject. The group offers support such as past exam questions, notes, and books to colleagues teaching or wishing to teach the discipline.

As teaching economic history progressed over the years, there was a realization that research and teaching had a bias towards environmental and sustainability issues. As such, when the university, in 2020, instructed faculties and departments to undergo what they called “disruptive programming,”Footnote 8 this was seen by the DEH as an opportunity to bring in discourses on sustainability. First, a workshop on environmental history funded by the International Consortium of Environmental History was organized in the department from 27 to 29 June 2019. A number of environmental history programs were agreed upon. With the curriculum review imposed on departments, a decision was made to change the department’s name to the “Department of Economic History and Sustainability Studies.” Under this department, new programs on environmental history and economic history and sustainable development were proposed. Unfortunately, these proposals were turned down by the university administration. The department was dissolved, and its programs were put under the newly minted Department of History Heritage and Knowledge Systems. A new undergraduate program, Heritage and Economic History, was introduced in place of the old Economic History program. The Master’s program was rebranded to MA African Economic History and Knowledge Systems.

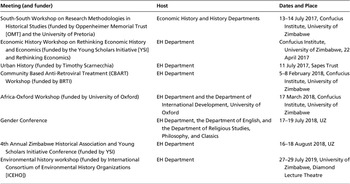

From my own perspective, the years 2017 to 2020 were the golden period for the department. For example, the intake of students increased steadily, attesting to the growing popularity of the discipline (see Figure 1 above). In 2019, it reached a peak intake of over 92 students. During this period, two MOUs were facilitated, one with Lund University in Sweden and another with Ben Gurion University of the Negev in Israel. The MOU with Lund University saw at least three lecturers being hosted by the Department of Economic History at UZ for periods ranging from 1 to 3 months. A PhD student in the Department of Economic History at UZ was also co-supervised successfully with a colleague, Erik Green, based at Lund University. There were also co-publications, joint grant applications for research, and exchange programs. The second MOU with Ben Gurion University culminated in a joint two-year project on Community Based Anti-Retroviral Treatment (CBART) and included the Biomedical Research and Training Institute (BRTI). The lead researcher was Anat Rosenthal, a medical anthropologist based at Ben Gurion University. Six students from the Department of Economic History were trained in research methods, data collection, and data analysis and became part of a team of researchers investigating factors that shaped the nature and extent of access to ARVs by individuals in rural communities.

Figure 1. February and August student intakes in the Department of Economic History, 2017 to 2020

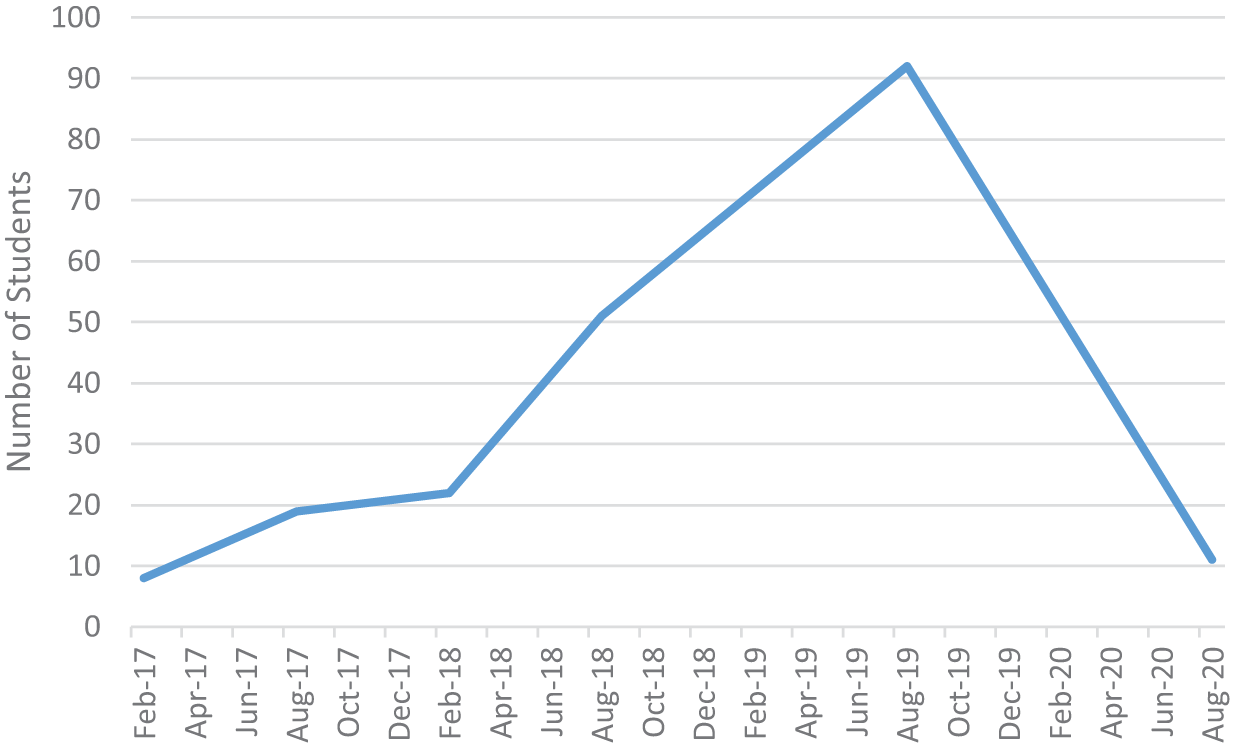

The department also became actively involved with organizing and hosting both local and international workshops and conferences. In 2017, the department began hosting alumni workshops, which included prospective, current, and past students in the department. Unfortunately, only two workshops were successfully held. Table 2 is a comprehensive tabulation of the meetings that were hosted by the Department.

Table 2. Workshops and conferences organized and/or hosted by the Department of Economic History.

The department was also able to increase its enrollment of women as students both at Masters and Undergraduate levels. This was a very important step, given that the department had gone for over a long time with only men as lecturers. As far as I can remember from my days as a student, there were never more than two women serving as lecturers in the department. Since I joined the department in 2009, there was never a woman serving as lecturer. For some, this was a non-issue because “merit is what counted.” In spite of these sentiments, a conscious effort was made in the department to encourage women to enroll in MA classes. By 2020, the department had appointed three women as staff members, two of whom were temporary-full-time lecturers and the other a teaching assistant.

Conclusion

I will conclude this piece by introducing the term epistuicide. Footnote 9 There have been a number of researches and scholarships around what has been called epistimicides, – that is, the killing of a peoples’ knowledge systems by another.Footnote 10 I introduce the term epistuicide to refer to situations where a people destroy their own knowledge systems. The history of the Department of Economic History is a classic case of epistuicide. It is a history of unrecognized effort. Broadly, this story demonstrates how internal dynamics, institutions, and systems derail and counter efforts at knowledge production from Africa. It would be incomplete to tell the story of the decline of the Department of Economic History without acknowledging the role of individuals who directly and indirectly worked against the department and what it stood for. From its inception, personalities and interventions by individuals shaped trends in the department. Indeed, the timing of the dissolution itself owed to the role played by individuals who did not share the vision and ambition of the department. Notwithstanding, economic historians from the department continue to hold a strong influence in academia, both locally and internationally. There has been increasing local recognition of local economic historians. For example, the current chairperson of the new Department of History Heritage and Knowledge Systems, Dr. B. Kusena, an economic historian, was invited to be part of the Zimbabwe Land Commission as an assessor. There are many more economic historians from the older generation who have made a mark locally. Our hope is that in its new form as Heritage and Economic History, the discipline builds on this mark and positively shapes academia, research, and development in unprecedented ways.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to my lengthy discussions with Dr. Joseph Mtisi and his feedback to my initial draft. This paper triggered so much debate between us but I am also happy that it brought back to him fond memories. Any errors found in this paper are entirely my own.