Introduction

In 1958, a Pokomo elder living with and alongside the Tana River in eastern Kenya petitioned the colonial state, complaining that the onset of irrigation developments there had destroyed communal riverine lands via flooding and dispossession.Footnote 1 These lands, codified by the state as belonging to the Crown, were essential emergency agricultural lands for the Pokomo community, where plants, shrubs, and beehives could all provide critical nutrition in the event of crop failure elsewhere. The access roads, pumps, and canal intakes imposed there by the state thus reified a materialist interpretation of the environment that separated land into a binary of barren and productive, erasing the web of values that the riverine ecosystem held for local communities.

Some 55 years later in 2001, Pokomo agriculturalists just a dozen or so miles away from the site of that initial complaint clashed with Orma herders, as both communities relied upon the river during a particularly potent drought. During the intervening years, state and private economic development projects had dispossessed local communities and upset delicate ecosystems across the length of the river in search of economic growth. In the ensuing violence, dozens of people died as the consequences of capitalist expansion alienated not only those whose shambas (farms) abutted the river but also diverse communities from across the wider arid region who relied upon, but held no legal claim to, the river.Footnote 2

While separate in time and nature, these two conflicts originate from a similar pressure point: a disjuncture between previously cooperative ways of living with the riverine ecosystem and the singularly extractive goals of outside actors. Moreover, contests over land and water frequently occur some distance from the physical sites of change (directly or indirectly) generating them. Dispossessed from the physical site of economic development, Pokomo and Orma anger urges us to consider African environments and environmental histories not as singular sites but as ecosystemic wholes. Development history on the continent largely relies upon analyses of particular projects with discrete boundaries and contributes to understandings of the environment that are tied to demarcated lands where development “happens.”Footnote 3 Alternatively, edited volumes provide much-needed geographic breadth while occasionally balkanizing sites or communities.Footnote 4 Instead, this article thinks through development as an ecosystem built upon vascular lineages between riverine and hinterland, catchment and floodplain, material and spiritual embodiments, flooding the traditional boundaries of environmental history.

In doing so, this article makes a case for the necessity of interpretive interdisciplinarity within the field of African environmental history that treats folklore and oral storytelling not only as historical artefacts or narrative sources,but as indicators of vibrant ecophilosophies, which hold potent social justice potential in the present. In this manner, the approach makes a creative case for historians to reimagine existing sources as intellectual histories of ethics, simultaneously alongside existing configurations of material and social analysis. Such work is by no means easy, given the limitations of colonial archives and anthropology, and is made all the more difficult in areas such as Tana River district where both local activism and scholarship are overlooked, owing to successive colonial and postcolonial states’ disregard for the region’s peoples. The river’s definition by outside actors as a specifically material resource places communities in permanent opposition to those actors’ economic goals. Valuing and representing forcefully erased ecophilosophies therefore requires casting a new eye over colonial, anthropological, or capitalist sources in the search for a counter-narrative.Footnote 5

The Tana River, the longest waterway in Kenya and the home of geographically consecutive and diverse forms of economic “development,” ties together numerous environmental understandings, knowledges, and prerogatives, and thus represents a compelling scenescape for reconceptualizing the nature of historical analyses of rural Africa. Specifically, this article argues that we must consciously think outside of the structures of colonial and racial capitalism if we are to historicize and guide discussions of future environmental mitigation procedures.Footnote 6 Capitalist problems cannot have capitalist solutions; solutions have long been consciously and repeatedly imposed upon buried indigenous knowledges and riverscapes that offer fertile solutions to current issues.

In stark contrast, rural African ecologies are (and have historically been) defined by numerous understandings of human-nature relationships based on symbiosis and mutual interdependence. Rooted in ubuntu, ecological knowledge such as ukama and others emphasize humanity’s embeddedness and reliance upon the natural world, and communities’ active engagement in that relationship.Footnote 7 Further, communities’ use of the land frequently remains rooted in tangible and micro-understandings of the environment, which are widely more sustainable and appropriate for their locations than the supposedly superior forms of development introduced by governments and NGOs. In engaging with oral testimonies, folklore, rumor, and environmental action, this article values rural ecophilosophies, alongside existing conceptions of Black and indigenous ecologies from scholars such as Katherine McKittrick, Kim Hester Williams, and LeiLani Nishime, to analyze the consequences of colonial capital alongside a plurality of socio-ecological relationships that must be treated as politically potent in their own right.Footnote 8 In particular, Nishime and Williams’ work in articulating the ways that Black and indigenous communities perceive, experience, and survive ecological racism is crucial to this article, as is their urging for academics to approach racial ecology in ways that foreground multiple ways of knowing and interacting with the environment.Footnote 9 Above all, this paper values those relationships as counter-points and paths-not-taken throughout the course of the twentieth century, and thinking in this manner enables us to identify exactly why these external forms of development are so destructive by moving away from an oversimplified “profitable or not” binary. Here, the article does so by explicitly contrasting pre- and early-colonial paradigms of environmental action with the slow application of colonial economic ideologies on the Tana River to demonstrate the clear and urgent divergences between local ecologies and external interventions.

In doing so, this article states clearly that colonial archives and postcolonial conceptions of the environment are both simultaneously implicated in and reliant upon capitalist structures via economic impositions or discursive erasure.Footnote 10 Within this rubric, colonized and marginalized populations, as well as their environments, are defined by their capitalist potential for energy, agriculture, or conservation.Footnote 11 Even where communities align with or join these projects, as is the case in Tana River in the latter half of the twentieth century, such participation should be seen as arising in part due to the ways that capitalist impulses have destabilized and erased former ways of living sustainability within a wide ecosystem. Whether individuals chose to seek employment, resist, or simply continue their existing lives in the orbit of these impositions, none of these should be considered to be an expression of weakness or passivity, and the terms of engagement and rejection around development have always been subject to negotiation and challenged in myriad unseen ways. Asymmetrical relationships of power between local communities and external actors make the outright rejection of development programs difficult, making petition, protest, and, indeed, outright avoidance as potent as other more direct forms of contest.

This article thus contributes to an awareness of how our sources, and the theoretical lenses through which we read them, can rebuild the vitality of intentionally overlooked ecological knowledges. In doing so, we can follow Micere Mugo’s urging that we consider local actors as scholars in their own right.Footnote 13 In unencumbering communal knowledge and action from capitalism’s entrenchment of the land or water as solely sources of revenue, environmental histories of Africa can and should engage with other sources, disciplines, and ways of knowing in a complementary manner. Precolonial, oral, cosmological, and coexistent ecophilosophies are thus critical nodes in building true environmental justice on a global scale that does not simply rely on realigning or tweaking existing forms of racial exploitation.

Precolonial Riverine Life

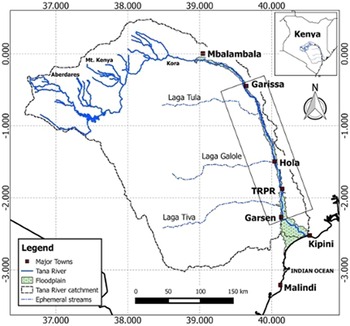

Stretching nearly 1,000 miles in length from the foothills of Mount Kenya to its delta at Kipini on the Indian Ocean coastline, the Tana River is perhaps the ideal example for modeling how environmental histories can benefit from a more capacious disciplinary approach (Map 1).Footnote 14 From the Seven Forks hydroelectric projects upstream to a host of irrigation schemes near Hola and Bura, as well as conservation areas in the delta region, the River hosts a plurality of attempts by national and international donors to monetize what is the longest stretch of river in Kenya. Alongside those economic development priorities, numerous Kenyan communities rely directly and indirectly on the water for their own survival, either for small scale agricultural shambas, riverine grazing, emergency crops, or varied sociocultural elements that for many are essential pillars of communal identity. Rather than simply a material entity, the waters of the Tana are instead imbued with multiple meanings and remembrances of largely equal order.

Map 1. Map of the Tana River, and its location within Kenya.Footnote 12

Numerous streams, tributaries, and subsurface waterways on the southern and eastern foothills of Mount Kenya and the Nyandarua mountains coalesce to feed the nation’s longest river, aided by streams and runoff from a drainage basin stretching from Kitui in the west to southwestern Somalia and the Indian Ocean coast in the east.Footnote 15 The Upper Tana between the highlands and Garissa is marked by a series of power stations producing over 65% of the nation’s electricity, constructed in the years after independence in 1963 with little regard for the socio-ecological conditions of the riverscape at large.Footnote 16 After falling to around 150 meters above sea level near Garissa, the river enters its middle portion, meandering through the otherwise semi-arid landscape and falling slowly. The plain here floods with increasing irregularity twice a year due to rains in the highlands, at which point the Tana bursts its shallow banks and inundates the surrounding landscape. The shallow lands of the surrounding area collect water and fertile sediments across a floodplain that ranges from 2km to 42km, providing vital agricultural grounds for riverine communities.Footnote 17 Further, the slow and winding course of the river remains susceptible to frequent redirection during floods, forming oxbow lakes and new channels. Passing Garsen, some 50 miles by water from the mouth of the Tana at Kipini, the river enters a deltaic floodplain that historically has been the most highly populated and regionally integrated section of the river.Footnote 18 The delta is further considered one of the most exceptionally biodiverse landscapes in the country, owing to the presence of numerous endemic species amongst hundreds of hectares of riverine forest.Footnote 19 Diverse forms of economic intervention like these agricultural, hydroelectric, and conservationist projects have been guided by a historical and current assessment of the riverine region as unused and empty wetlands and as a fertile site of water grabbing for capitalized agriculture.Footnote 20

The major riverine population of the Tana, downstream of Mbalambala at least, is the Pokomo community.Footnote 21 The Pokomo ethnic group at large was historically made up of four relatively self-embodied sections or kyeti (the Lower, Upper, Welwan, and Munyo Yaya), each further organized into 13 subgroups around distinct sub-clans, centered around common ancestries.Footnote 22 These subclans or clan alliances reside on geographically consecutive muicho (or sections) of the river, with the Upper-Lower Pokomo boundary historically laying between the villages of Ndera in the north and Mwina below.Footnote 23 Over time, the population of the district has increased from 16,355 in 1948 to approximately 100,000 in 2019.Footnote 24

As Pokomo author Mikael Samson Kirungu wrote, Pokomo life has historically been attached to and largely reliant on the Tana.Footnote 25 Indeed, the name itself is an anglicized bastardization of Tsana, the Pokomo word for “river,” and a reflection that this was a key body of water for many in the region.Footnote 26 Beyond a simple spatial marker or a site of residence, the Tana should be considered a vibrant actor within Pokomo communities across its entire length. Its importance is perhaps best embodied by the early twentieth-century aphorism “the Tsana is our brother.”Footnote 27 As a Pokomo brother (and son) in the early twentieth century would labor on the family shamba to produce rice, bananas, or maize before receiving a parcel of his father’s land upon marriage, so the river acted simultaneously as both a singular agent and an integral contributor to community life along its banks.Footnote 28 The Tana and the community are thus given life by the other’s presence, embodied by the proverb maji ni mugeni (water is a welcome guest.)Footnote 29 Such was this centrality that the Pokomo mwaka (year) was tied to the arrival of the sika and kilimo, or long and short rains.

Such reciprocity extended to the practical role played by the river in day-to-day life. Populations in the middle Tana region relied on the river’s waters for agricultural production based on riverine cropping, and as such it was illegal to own river water or forests due to their communal necessity.Footnote 30 The reliance upon flood recession agriculture saw rice planted in flooded areas and maize in less saturated hinterlands of the plain, and introduced bananas and other crops on higher, drier ground as subsidiary rations. In the event of crop failure, fruits from the doum palm and lilypad seeds acted as emergency crops, alongside the many varieties of fish endemic to the river.Footnote 31 Communal prohibitions on the destruction of crocodile eggs and the fatalism of Pokomo hunting songs, which acknowledge the reciprocal need of human and crocodile to hunt one another, both point towards a sustainable codependence within Tana socio-ecological articulations.Footnote 32 Finally, the river also provided the bulk of economic resources, as nets, spears, baskets, and traps were all fashioned out of riverine resources for sale into local and coastal markets, supplementing income received from migrants to the coast.

Material needs also bled into social, political, and religious performance. Those punished for crimes beyond redemption were sacrificed to the crocodiles, while the productivity and consistency of the river were both the requested through numerous cosmological rituals.Footnote 33 In these acts, the river again was host to the non- and more-than-human elements of Pokomo society, as evidenced by Peter Nzuki’s observation of funeral rights that saw community elders wade into the river and pray to nkoma spirits.Footnote 34 These nkoma are considered to be dynamic spirits subordinate below a higher God and residing within nature, and are the subjects of ritual prayer or offerings for rain, crops, or cures.Footnote 35 Linking the material and spiritual capacities of the river were the wakijo (or community elders) who had the capacity to requisition and redistribute food and resources during times of need on the basis of their apparent connection with the spiritual world. The secrets of the wakijo were limited to elder men who had proven their leadership throughout their lifetime, and conferred the right to operate the ngadsi drum. The threatening sound of the drum was claimed by the wakijo to be a grove-dwelling spirit, whose calls demanded donations of rice, maize, and other crops to stave off violence and ensure peace. Wakijo were banned from revealing the true source of the noise to the community at large in order to uphold the ritual, and their ownership and utilization of the ngadsi, prior to the predations of colonial capitalism, acted as a source of communal feasts and relief, especially during dry periods.Footnote 36

The linear connection between riverine production, ritual spirituality, and resource distribution more fully reveals the importance of the Tana’s consistent place within Pokomo life. However, the arrival of particularly Christian missionaries in the late nineteenth century saw communal ngadsi rituals terminated. Most Tana Pokomo communities converted (forcibly or voluntarily) to either Christianity or Islam in the late nineteenth century due to the creep of British and German missionary activity from the south and incursions by Somali and Orma from the north.Footnote 37 More relevant for our purposes, however, is the changing class dynamics of Pokomo communities following the establishment of British rule, as cash tax requirements and capital accumulation amongst elder community members drew resentment from younger landholders.Footnote 38

Of course, it was (and is) not simply Pokomo communities who rely upon the Tana for their livelihoods, as the district at large is inhabited by Orma, Wardei, Somali, Malakote, Munyoyaya, Wata, Bajuni and Mijikenda communities. The Orma are the largest pastoralist community in the region and have relied since the late-nineteenth century upon the western banks of the Tana for dry season grazing and watering, particularly following the community’s defeat to Somali incursions in the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 39 While pastoralism as a whole has been largely undermined by colonial and postcolonial attempts to settle transhumant communities and introduce diversified economies, the Orma have lost out more significantly than similar communities in northern Kenya by virtue of the economic potential of the Tana and its priority place within the development framework.Footnote 40

Those trends hold true across the Orma community at large despite internal divergences. Those Orma residing within the Tana delta, described as ch’affa after the floodplain itself or warr tezo, meaning “households that stay put,” are traditionally more settled thanks to the fertile nature of the land and its capacity for housing higher population densities.Footnote 41 These households retain stock holdings but are less reliant upon pastoralism as a mode of production. In contrast, those upstream remaining within the pastoral nomadic economy, the warr godana or “households that move,” rely upon the Tana for dry season grazing, while utilizing hinterland wells during the wet season.Footnote 42 During dry season, both herds moved closer to the river to take advantage of water and grazing. However, the Tana region at large was considered lusher than many of the pastoral landscapes of northern Kenya, meaning herd sizes tended to be larger and more productive.Footnote 43 Even during times of drought when the wells dried up, the river provided critical resources that prevented mass death on the same scale as could be seen elsewhere.

The modern bifurcation of pastoral/agricultural ignores the mutual intelligibility and interdependence of Orma and Pokomo especially in the pre- and early colonial era. Particularly, Nene Mburu and Norman Townsend have both shown that Pokomo and Orma communities traded widely with one another, owing to the differing ecological niches that each occupied, while also mediating community-led resource sharing agreements.Footnote 44 Specifically, the ecological boundary between riverine agricultural land and arid grazing grounds marked something of an ethnic boundary, while access to the river was granted regularly by community elders in the pre- and early colonial period. Agricultural waste or the remnants of cultivated crops provided important fodder for cattle, whose manure provided important fertilization for the year ahead. Furthermore, floodplain land not occupied or claimed by Pokomo families could also be settled by Orma herders, with their usage rights to those areas conferring relatively stable ownership.Footnote 45 The socioeconomic ecosystem here thus offered a degree of balance in times of good rain or flood, and reveals the fallacy of contemporary discourses surrounding the region that cite conflict between pastoral and riverine communities as an age-old inevitability.Footnote 46

The balance offered by coexistence and interdependence, however, suffered under the oppression of colonial rule. The Tana’s status as the colony’s longest river marked it out as a site of possible exploitation early on, and indeed both colonial and postcolonial authors have continually narrated the riverscape as an unexploited Eden. That framing, of course, intentionally undermines generations of migration, trade, and integration into regional economies. In addition to barter relationships with Orma, Somali, and Wardei communities, Pokomo communities across the length of the river engaged in trade with coastal Swahili partners as middle agents in the ivory trade, and by the provision of grains or artisanal goods in return for cloth, beads, and iron goods.Footnote 47 Relations with Witu and Lamu in particular tied Pokomo communities to a much wider network of goods and services defined largely by equitable standing, despite claims to contrary by Swahili leaders during negotiations with the German and British in the late nineteenth century.Footnote 48 Community prosperity was further bolstered by trade with Arab merchants near Kau who offered pearls, cowries, and shells as mediums of exchange.Footnote 49 Archaeological discoveries around that town include Chinese and Islamic ceramic wares while so-called Tana wares dating back to the seventh century have been found along the coast of east Africa as far as Zanzibar, suggesting a much wider circulation within the Indian Ocean littoral.Footnote 50

With that said, the arrival of first missionaries and then colonial agents in the nineteenth and early twentieth century began to pull the Tana River further into an explicitly capitalist gravitational orbit. In the first instance, colonial administration brought tangible changes in the value of goods and labor through the medium of taxation. Trade and barter could no longer rely upon existing mediums of exchange, as poll tax ordinances were to be paid to regional administrators in cash rather than goods. As colonial administrators for Tana River tended to reside in Lamu or Kipini through the majority of the colonial era, Pokomo families were able to avoid these taxes relatively easily. Yet the changes in exchange value brought about by cash taxation nonetheless heralded a new era. Rather than the exchange of goods for equally valued necessities from other communities, some agricultural produce now had to be bought and sold for cash, while poorer individuals migrated to Mombasa or Nairobi to labor on construction projects. Production thus shifted from subsistence and tradeable goods to those crops that could be sold for the highest price, particularly maize, due to the higher earning potential and lesser labor requirements.Footnote 51 With surpluses being deemphasized in favor of cash-earning produce for tax payments, critical emergency resources for low flood or rain years shrank.

The economic transition wrought by colonial rule quickly revealed the inherent failings of colonial capitalism. Exploitation relied upon clear and consistent production of goods, where annual yields could be predicted and revenue could be forecast reliably. However, consistency and predictability were qualities the river did not embody, and localized production amongst Pokomo communities reflected that variance. The near-entirety of Pokomo livelihoods revolved around mitigating the river’s fickle nature, from the cultivation of plots in multiple locations and gradients to the planting of various crops at different stages of the water line. Such contingency stood at odds with European perceptions of good production however, leading to a growing stereotype of environmental impotence and unproductivity amongst the Pokomo. In casting riverine and delta villages in such a manner, administrators and agronomists justified the imposition of major development projects designed to exploit properly the economic potential of the river. Productive potential became the sole attribute by which the river and its populations were defined.

“Development”

Beginning in the 1930s, state officials began to take a key interest in not only taxing the region but also expanding its productive base. A 1934 survey by irrigation experts sought to identify areas for possible agricultural schemes along the river.Footnote 52 Travelling the length of the Tana, D. G. Harris and H. C. Sampson identified numerous barriers that the river erected against its potential exploitation. Impervious soils, slow gradients, the tortuous course of the river and its oxbow lakes collectively appeared to be a series of guardrails against colonial objectives, leaving the flat barras (plains) on the far sides of the floodplain as the only conceivable locations for irrigation.Footnote 53 Even there, however, barriers arose due to the potential cost of canalization and pumping. As such, Harris and Sampson deemed the stretch of river upstream of Garissa as the prime region for development, while the middle reaches were considered to be far too expensive and unstable for any “system of agriculture of which permanence is a feature.”Footnote 54

These qualifiers contained an implicit acknowledgement regarding the sustainability of Pokomo river use, yet the balance of the report makes the case that irrigation schemes colony-wide must instead enforce settled agriculture and cash crops, rather than shifting subsistence.Footnote 55 They claimed that although “the African has, through centuries of experience, acquired a considerable knowledge […] this knowledge is suited rather to shifting agriculture on rain-fed areas than to the artificial seasons and the permanent occupation of the land which irrigation imposes.”Footnote 56 Further, Harris and Sampson urged that any irrigation scheme should introduce “new methods of cultivation, new principles of land tenure, and indeed a whole new agriculture.”Footnote 57 In asserting the necessity, significance, and primacy of settled and irrigated agriculture over all else, the authors and their patrons in Nairobi and London further entrenched the erasure of non-extractive production along the Tana. Simultaneously, they sowed the first seeds of Pokomo political and economic marginalization in claiming that no form of economic development on the floodplains by the colonial state (irrigated or otherwise) could be imposed and that any assistance would be limited to healthcare and education.Footnote 58

Although no action was taken on the Harris and Sampson proposal or a subsequent proposal in a 1948 report, owing to the enormous costs involved in an irrigation project on the Upper Tana, the institutional priorities that both embodied continued to germinate throughout state attitudes to the floodplain.Footnote 59 The first sprouting shoots of those attitudes occurred in 1952, when a global rice shortage redrew attention to the region around Hola, home of the Zubaki subclan of the Pokomo.Footnote 60 Hola itself should be considered a perfect embodiment of the Tana ecosystem’s overlapping and interstitial nature, as a multidenominational settlement divided between Christian, Islamic, and indigenous religious communities.Footnote 61 The coexistent and mutually accommodating settlements around Hola belied the ordering rationales of colonial rule and gestured towards the resilience of indigeneity within the wider riverscape. Further, the choice of a developmental site there in the early 1950s committed the state to negotiations over both the economic framework for lease and the sociocultural significance of the riverine ecology there.

In response to the rice shortage, colonial officials in Nairobi sought to co-opt indigenous agricultural practices around Hola by channeling Tana waters in delineated rice paddies within one of the areas’ numerous oxbow lakes.Footnote 62 Initially leasing the land from Zubaki owners for a price based on the quantity of maize each could produce on the land they were giving up, officials constructed protective bunds and pumped water through a narrow channel to control the level.Footnote 63 Pokomo families leasing the land were given the option to labor on the project for a wage, potentially doubling the economic possibilities the scheme offered on the eastward bank. The agreement contained a quintessentially capitalist sleight of hand by the state however, as the earning potential of the rice they hoped to grow far outweighed the price of the maize upon which the agreement with Pokomo landholders was based. Profits were thus to be appropriated both financially and culturally from Pokomo knowledge and agricultural programs, yet for many around Hola the project appeared to be largely a net positive – if the minutes of local barazas (public meetings) are to be believed – due to the additional income it provided that could help to pay off tax burdens or debt to local shop-owners, while requiring relatively little sacrifice of riverine land. The early “Left Bank Scheme” thus appeared to be a Venn-like middle ground between wholesale capitalist extraction and indigenous ways of knowing and living with the river, allowing Pokomo in the region to retain primary cultural ownership of their resources, in keeping with pre- and early-colonial experiences.Footnote 64

That overlap would soon be lost, buried beneath political and economic priorities as well as the ever-present environmental variability of the Tana. By the time equipment had arrived and been installed by European and African agricultural officers in 1953, the global rice shortage had ended, and the profitability of the scheme was in doubt.Footnote 65 Without the guarantee of profits from rice production, Ministry of Agriculture officials cut the scheme first in half to just thirty acres, of which ten would be used to test the properties of the riverine soil, and then again to fifteen in 1954.Footnote 66 The majority of landowners abandoned the project as it transitioned to this experimental phase, with the lack of viable and consistent income making a return to previous riverine production more appealing. In doing so, many around Hola withheld both labor and produce from the state after recognizing the inequity of the partnership. The state archives after 1953 are littered with arrests and official complaints about the rapid expansion of the existing black market trade in rice and other cash crops, as residents tried to avoid harsh colonial taxation which evidently offered little in return.Footnote 67 Simultaneously, the growing developmental state generated increased complaints from Pokomo residents to coastal politicians such as Paul Pakia and, later, Ronald Ngala regarding land theft and declining investment.Footnote 68 As if to justify those complaints, state officials for their part cautioned that no further promises should be made to Pokomo families around Hola about their involvement in future development projects, for fear that they would preclude “other races and tribes” from projects in the area.Footnote 69 However, these instances demonstrate the ways that residents around Hola adapted their responses to state intervention using the new tools of political power, while also melding these tactics with the reinvigoration of longer-term forms of riverine trade and land claims.

The onset of the Mau Mau Emergency shifted political-economic priorities in the wider colony, while also raising the possibility for a more expansive and explicitly productive development project in the region. While the socio-ecological factors that had made the area around Hola seem so unsuitable for irrigation to Harris and Sampson had not changed, the presence of officers and equipment there drew the colonial eye ever more closely to the river there. With no promise of quick profit due to the colonial state’s own inability to anticipate the vagaries of riverine agriculture, officials swiftly transitioned to a more expansive and labor-intensive proposition that served dual economic and security purposes. As an economically marginal area, the Tana appeared to be the perfect location for this blend, and soon after the publication of the Swynnerton Plan in 1954, detention quarters were constructed on the westerly bank of the river abutting the Pokomo land unit.Footnote 70 Without the abundance of detained labor that the Emergency had provided, Provincial Agricultural Officer George Cowley warned that “it is unlikely that anything useful will ever be achieved there.”Footnote 71

Eighty predominantly Kikuyu detainees from central Kenya arrived in June 1955 and were immediately tasked with the digging the three-mile canal from the Tana to the future irrigated plots, constructing pipelines and accommodations, and delineating the extent of the plots themselves.Footnote 72 These pipelines and canals stretched through the Pokomo reserve lands and into Crown Lands, meaning that there was no need to lease large tracts of land as had been the case on the Left Bank project. While there were likely pragmatic reasons for this, as it allowed officials carte blanche to impose the scheme as they pleased, it also suggests the possible unwillingness of riverine communities to lease their land or provide labor to the project following their previous abandonment in 1953. Simultaneously, discussions were underway amongst prisons and development officials in Nairobi as to whether any irrigation project near Hola could double as a resettlement scheme as well as a detention camp. Over the following years, officials solicited volunteers amongst the detained population to move permanently to Hola, where they and their families could reside and farm on and within irrigated villages.Footnote 73 Alongside this, the size of the irrigation scheme on the opaquely named Right Bank Scheme increased to over 1200 acres by the end of 1959.Footnote 74

Alongside the soon-to-be infamous Hola detention camp was a fully functioning water development project seeking to create profitability and a new hydrologic reality alongside existing riverine livelihoods.Footnote 75 Experimental shambas and tenants’ plots were used by the Ministry of Agriculture to test a range of factors, ranging from soil salinity to fertilizer comparisons and drainage properties. Soon after, an abundant array of crops primarily geared toward sale and export were tested, with varying degrees of success. Cash crops ranging from colonial staples like groundnuts, cotton, and tobacco to greengram, sweet potato, and sorghum were planted across the experimental shambas, as officials sought to finalize exactly which of these products would best acclimatize to the local ecology.Footnote 76 Many indeed did not, leading to a variety of supplementary measures designed to keep produce alive, which included the planting of windbreaking citrus trees.Footnote 77 Nonetheless, the scale of financing and ecological intervention on the Tana Irrigation Scheme dwarfed any assistance given to the Pokomo families living astride the river, and indeed actively undermined the strategies of resiliency and contingency on which they relied.

For the Zubaki Pokomo around Hola, the ecological failings of state agriculturalists were irrelevant in comparison to the socio-ecological issues caused by major irrigation works in the region. Archival sources are limited in their utility for understanding how the Scheme impacted Pokomo communities on a day-to-day basis, but community resistance and an awareness of prior forms of ecological engagement demonstrate a pervasive shift. Villagers petitioned the state continuously up to the end of 1959 due to the destruction of banana trees during construction work, trees that were vital for community resilience during times of drought and poor flooding.Footnote 78 At other times, these social changes brought violence and alleged disorder in nearby townships, as dispossessed or crop-poor individuals railed against incoming forms of exploitation.Footnote 79 These acts particularly targeted Arab traders who were deemed to be financially exploiting Pokomo in the region by artificially inflating the price of food in nearby stores following drought or declines in family production, or by refusing to pay the market rate for Pokomo maize.Footnote 80

Similarly, controversy arose in 1955 when it was discovered that some 325 acres of the prison encampment and irrigation project lay within the Native Land Unit (NLU) apportioned to the Pokomo community under the Native Lands (Trust) Ordinance.Footnote 81 Despite nominal financial commitments to the local African District Council (ADC) in payment for this land, community leaders continually agitated for proper payment and for recognition of non-title forms of land recognition.Footnote 82 In 1958, leaders of the ADC asked that Scheme officials recognize specifically the placement of beehives built on unoccupied riverine lands, a community symbol of a claim to territory.Footnote 83 Even though some of these lay within Crown land rather than the NLU, under traditional customs, unused land was available for any member or newcomer to cultivate. The ADC representatives went further, however, in stating that occupation and use rights extended to Orma pastoralists and the consumption of hinterland scrub by their stock. The ADC thus argued for a more capacious definition of indigenous land rights that acknowledged the symbiotic and mutually complimentary ecosystem of the Tana for all communities that predated colonial annexation, and which served to protect access rights for multiple, economically and spatially distinct peoples.Footnote 84 These requests were rejected, and compensation was only given for the seizure of land that lay within the reserve.Footnote 85

The end of the Emergency and the slow return of Kikuyu detainees to their homelands following the Hola massacre in 1959 offered a brief window for change in the colonial calculations for the Tana River, a window that was ultimately barred by economic impulses. Rather than reorient perspectives on the river away from a single-minded drive to shoehorn communities into settled agriculture and capitalist production imperatives that the environment simply could not sustain, scheme managers instead took a business-as-usual approach that ignored state failings. Having tried in vain to convince detainees to remain on the project as tenants, or spur the migration of families from the “overpopulated” central highlands, project managers finally began to allow Pokomo families to tend the irrigated plots on the Tana Scheme.Footnote 86 By March 1961, 47 Pokomo had signed leases for the experimental shambas alongside 53 Kikuyu, yet, by this stage, the rigidities of colonial extraction had inescapably altered the material and social conditions of the river and forced many in the immediate region to either request plots on the Scheme or accept roles as informal laborers. Participation here was willing and it was sought, yet in taking a longer-term view of the river we can understand how that participation was made more critical by the generalized undermining of riverine agriculture as a source of production, trade, or growth.

The transition from colony to the Republic of Kenya in 1963 signaled widespread political and social change across the nation, as well as a rhetorical if not always pervasive commitment to African Socialism.Footnote 87 Rather than cutting losses on the scheme or reorienting its goals to more fully integrate new agriculture into the existing riverine social ecosystem, postcolonial scheme leadership instead fixated on enforcing the area’s integration into globalized western developmental paradigms. A 1962 report by the World Bank surveyed the length of the Tana and retained the conclusion that the river should host irrigated agricultural projects.Footnote 88 For the communities reliant on the Tana, however, the promise of an egalitarian dawn were largely unfulfilled due to the region’s continued marginalization. Between 1963 and 1966, the UN Development Programme and Food and Agriculture Organization surveys visited Kenya with the express goal of increasing agricultural output and the development of the export economy, while the British officials in charge of the Tana Scheme in particular remained consistent prior to the project’s takeover by the newly formed National Irrigation Board in 1966.Footnote 89 In this manner, Hola was integrated into both national and global networks of production, which relied upon centralized guidance and the erasure of communal forms of governance and production. Simultaneously, dam construction at Masinga and elsewhere on the Seven Forks project upstream abruptly changed the flooding and flow regime of the Tana.Footnote 90

Both inside and outside of the irrigation schemes then, economic decision-making processes remained consistent with the colonial era, while the conditions faced by Pokomo and Orma communities within the riverine ecosystem fluctuated. Many residents from the closet three locations chose to take up plots on the Scheme, to the extent that there was a consistent waiting list for access, and as such we should consider these villagers to be participants rather than bystanders to the project. Footnote 91 Yet that very fact reveals the damage done by the project; participation arose due to a lack of support elsewhere and the undermining of existing riverine agriculture via land annexation, river changes, and population growth. Relative to the riverine region at large, the Scheme dominated economic investment as villages along the middle Tana continued to rely on informal production and remittances from community members who had moved to Mombasa or Nairobi. Further, state investment along the Tana amounted to little more than piecemeal investments in education, healthcare, and infrastructure that were relatively insignificant in comparison to elsewhere in the nation. These were joined by a plethora of smaller irrigation projects geared towards subsistence production, allegedly liberating Pokomo villages from shifting agriculture and toward more consistent and reliable subsistence, despite the long-term proof that sustainable shifting approaches continued to be the most successful form of production in the region.Footnote 92 To demonstrate this point, as Patrick Alila has shown in his work on smallholder agriculture, those Rural Development Fund interventions failed to provide any of the social infrastructure necessary for these farmers, be that communal assistance, investment in resources and equipment, or marketing assistance.Footnote 93

These changes allowed some communities to flourish, however, as they took advantage of the arrival of newcomers by through the sale of goods into major projects. As a result, modes of production and distribution gravitated toward the major irrigation schemes along the river, whose tenants proved a fertile market for firewood, rice, and maize in return for remittances and cash payments.Footnote 94 The terms of reciprocity on offer here are interesting, in that tenant earnings from what was by 1980 predominantly a cotton-growing scheme were used to purchase those same goods and resources (maize, bananas, baskets, etc.) that had been previously bartered for or shared prior to colonial interventions.Footnote 95 The net contribution of economic development in the region, and the associated dispossession and social distortion it had offered to both Pokomo and Orma over the previous 30 years, essentially resulted in the continued circulation of preexisting resources. Simultaneously, the continued annexation of land for development and the changing regime of the river accelerated a reliance upon famine assistance, which had been introduced by the colonial state or the proletarianization of nearby villages.

For Orma communities, the forms of land annexation and market economics introduced by irrigation schemes altered patterns of epicyclical pastoralism. While some 60% of the Orma population along the Galole tributary near Hola remained engaged in nomadic pastoralism, tendencies toward settlement accelerated during the late-colonial era.Footnote 96 Under the twin duresses of drought and taxation, the 40% of families residing in villages and with smaller cattle holdings sold off their stock to meat merchants to buy subsistence goods or to pay debts to shopkeeper and tax officials. No longer self-sufficient in terms of food or labor, these families settled close to villages sent their remaining stock to remote cattle camps run by richer herders who employed generally younger men.Footnote 97 With fewer stock on hand these poorer members of the village were tied ever more closely to the market economy, while those who retained small numbers of stock on-hand were left far more susceptible to drought in the hinterland and disbarment from the Tana during dry season. With riverine production declining due to the growth of irrigation projects, and accelerating water shortages in the hinterland, pastoralists were forced into patron-client relationships to afford food. By interfering with preexisting reciprocal trade and access relationships between Orma and Pokomo, the state had undermined critical levers of pastoral life. Under these circumstances, only the richer herders could remain self-sufficient.

Ripples of Colonial Capitalism

What, then, was the point of the Tana Irrigation Scheme? During years of good production on the Scheme, the profits that accrued certainly benefited tenants, villagers, and the state. These years were few and far between, however, as tenancy costs and the price of equipment, fertilizer, and water meant that most residents struggled to break even in years of drought or poor pricing, such as in 1966 and 1967.Footnote 98 For the state, those years proved catastrophic, as the Scheme relied upon National Irrigation Board (NIB) subsidies to break even; annual reports from Hola in the late 1970s and early 1980s noticeably show that the Tana Scheme never ran a loss, by virtue of annual “Grants from Head Office” that matched the losses being made by the scheme.Footnote 99 Such was the inconsistency of the returns on the Scheme, and the terms of tenancy that allowed the NIB to pay whatever they deemed fit for cotton, that many in the surrounding communities felt that “the work just doesn’t seem worth it.”Footnote 100 Local residents responded by turning to informal labor or migration, which each offered seemingly better terms of engagement. By 1989, the Scheme housed 678 tenants on 867 hectares, and waiting lists for plots fluctuated throughout the period.Footnote 101

That year however saw the rigidity of capitalized cash crop agriculture exposed at Hola. As had been prophesied by the contingencies of Pokomo livelihoods for generations and by colonial surveyors 65 years beforehand, heavy flooding and rains in the middle portion of the river dramatically altered the course of the river. Where intake canals and pumps had previously rerouted water into the irrigated plots on the Irrigation Scheme and to small scale shambas built by Pokomo families with Rural Development Funding, a dry riverbed portended struggle. Changing course just above Hola, the redirection brought almost overnight destitution to the Tana Irrigation Scheme, as tenants departed and houses and machinery were left abandoned in an all-too-predictable demonstration of the deficiencies of colonial capitalism. The second half of the century had seen an increasing obsession on behalf of state and international investors to bind and constrict the land and waters of the Tana region, seeking to make them knowable and commodifiable in a way that would foster predictable yields and stable production platforms. All of this planning could not restrain the river’s natural impulses, however.Footnote 102

Placing the imposition of extractive capitalist ideology alongside community-level associations with the riverine landscape reveals the deep fissures between those two positions, and the gravity of losses incurred by Pokomo and Orma pastoralists across the middle Tana. For Pokomo communities, the river’s change in course drew it away from the small-scale irrigation works implemented over the previous decades. Further, changing flow conditions arising due to the upstream Kaimbere and Masinga Dams blocked the flow of fertile sediment downstream and abruptly shifted the flood regime of the river, both of which dramatically undermined the subsistence productivity of riverine agriculture and the contingent food sources it provided.Footnote 103 Downstream of Hola, the annexation of land for ranching projects, agricultural schemes (managed by the Tana and Athi River Development Authority also charged with the maintenance of the dams), and the Tana River Primate Reserve have all encroached upon the resiliency of riverine and pastoral communities.Footnote 104 Across the Tana’s length then, the economic potentiality of the water and the electrical, agricultural, ecotourist value it embodies reduces the river to a tool of growth, as opposed to a living actor working in concert with regional communities.

That ideological imposition has, predictably, driven conflict in the present. As an arid region with sparse water supplies, Tana River county as a whole stands to suffer greatly from rising global temperatures and changes in rainfall patterns, while economic development projects like the Masinga Dam or the Bura and Tana Schemes further ecological change and drive a wedge between indigenous communities and their lands. These diverse impositions, and their geneses in colonial era planning documents, demonstrate a revealing continuity between colonial-era drive for production at any cost and the current state’s economic goals. The Kenyan state’s drive since 2001 to privatize trust and communal lands stands at odds with preexisting forms of indigenous collaboration.Footnote 105 The process of adjudicating and titling riverside plots has raised fears amongst pastoral Orma communities that their access to the river will be severely curtailed, while Pokomo communities fear the increasing instances of crop destruction by thirsty stock.Footnote 106 These overlaps will be especially prevalent, as rising temperatures and increasing incidences of drought reduce the viability of hinterland wells and tributaries during the dry season.

During times of particular climatic hardship, this antagonism has led to widespread violence, stoked by local politicians who play on communal fears of economic marginalization, as has been the case in 2001 and 2012.Footnote 107 With state investment increasingly dependent on political allegiances to the central government, intercommunal resentment is a potent tool for leaders seeking to entrench their own positions locally. Simultaneously, national actors have been notable for their absence from the region, reinforcing the perception that it is the economic resource potential of the river as opposed to the lives of constituents that state officials are concerned with.Footnote 108 In doing so, environmental and ecological hardships are weaponized by way of rumor and of enclosure.Footnote 109 Such is the level of competition: intercommunal cooperation has given way to distrust, with farmers claiming that “each group is fighting for ownership of the river” while defining access in ethnic terms.Footnote 110 These conflicts, and their blossoming in the absence or unviability of historical famine mitigation strategies, such as hunting and gathering or flood recession agriculture, profoundly reveal the social consequences of ecological change in the region.

Ahead of the Kenyan General Election in 2022, the Tana River has returned to the national spotlight as widespread drought and water shortages have left the county in a precarious position. Across the district, thousands of stock have died due to water shortages, which threaten both human and non-human lives and livelihoods, and have seen Orma herders trek over 300 miles in search of fodder and water.Footnote 111 Food insecurity affects possibly 80% of the county population, and community members in Hola called on the County and National governments in September 2021 to relinquish control of their holdings on the Tana Irrigation Scheme so they can be handed back to citizens.Footnote 112 The move would allow residents to produce their own food for subsistence and for market, but has been met with pushback by officials. Instead, the national government has promised to invest close to eight million shillings in the Bura and Tana projects as well as smaller demonstration plots, where produce will be cultivated both for local consumption and market sale.Footnote 113 The investment stands as part of a much wider promised investment in the county, as officials seek to make “Tana a destination for trade and investment” via developments in agriculture, aquaculture, the livestock trade, and industrial processing.Footnote 114 In continuing to prioritize forms of public-private partnership such as irrigation schemes against a backdrop of drought and falling water tables, endemic resource conflict and stock losses are perhaps inevitable as long as communities themselves are barred from managing and mediating access to the river. However, community complaints and calls for restitution also signify the continuing vitality of Pokomo and Orma claims to land in the face of neo-colonial power structures, as well as the potent flexibility of the riverine livelihoods that persist.

Conclusion

In the long term, the impact of capitalist categorization and colonial subjugation on Pokomo and pastoralist ways of life have been manifest. In particular, those impositions have rendered endangered past ways of knowing and engaging with the environment, while also stripping both personhood and ecological vibrancy from the river at large through the demise of riverine crops and the dispossession of communities from traditional rive and forest lands. Within colonial archives, postcolonial assessments of the river, and current development discourses, the Tana is defined by its economic possibilities above all else. In describing its waters as primarily a source for irrigation, for building materials, or as holding a “high value” for recession agriculture, colonial capitalism and its descendants are made natural, inevitable.Footnote 115 Under such conditions, the Pokomo and Orma communities of the Tana River are forced to align themselves with the commodification and exploitation of the riverscape in order to survive within a globalized and neoliberal economic system.

A historical analysis of the Tana must engage not only with current materialist assessments of its potential but also the temporal and geographic breadth of engagements with its waters, as well as the tributary-like understandings of its importance to diverse groups that coalesce into the whole. In encouraging such capaciousness, written texts and archives must be complicated by forms of indigenous testimony such as folklore and new interpretative tools stemming from fields of ecophilosophy and racial ecologies. Environmental historians have key perspectives with which to shape climate and environmental justice discourses on a global scale, yet the colonial archives, and our treatment of them, frequently, if not always, reifies capitalist interpretations of the environment that center its extractive potentials. Liberating this riverscape from economy-first analyses points a path forward for more equitable, sustainable, and symbiotic forms of resource use that recognize the mutual engagement between community and environment. Rehabilitating these environmental ethics on a local scale continentally is thus a key path forward for Africanist environmental historians in increasing the political and activist potency of our work.