I

Between 1726 and 1751, the Venetian health officials of the Ionian island of Zante (Zakynthos) were preoccupied with the regular movement of seasonal agricultural workers from the Ottoman territories of Morea (southern Greece) returning to the island after the harvest.Footnote 1 After arriving on Zante, all workers had to be quarantined: an average of almost 2,000 people needed to be sheltered and fed every year.Footnote 2 These movements were of great concern to the prior of the quarantine station who managed the logistics of quarantine. The workers, being ‘very impatient and troublesome’ given the precarious conditions of quarantine, sparked episodes of sporadic unrest.Footnote 3 A similar regular movement of workers also concerned the authorities on the island of Cephalonia where, until 1741 when the quarantine centre (lazzaretto) was built, the whole island was put under quarantine at the return of the seasonal workers.Footnote 4

The Venetian Health Magistracy (Provveditori e Sopraprovveditori alla Sanità) went to great lengths to ensure that everyone and everything coming from Morea to its islands would be carefully quarantined. Venice, along with the other Western and Central European powers in the Mediterranean, considered plague an endemic disease of the Ottoman territories. On this assumption, a transnational system of quarantine stations was set up by early modern Central and Western Mediterranean states in their ports and trading centres.Footnote 5 This system employed sophisticated and co-ordinated quarantine practices to allow safe commercial exchanges with cities occasionally hit by epidemics and, above all, with the Ottoman Levant, the Barbary Coast, and neighbouring regions. First adopted in 1377 by the Republic of Ragusa (Dubrovnik), quarantine regulations were developed in the fifteenth century by the Venetian Republic; between the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries the Serenissima established a complex system of quarantine centres (pl. lazzaretti, sing. lazzaretto) in its territories (including the northern inland territories – Terraferma – and territories in the Adriatic and Ionian Sea).Footnote 6 During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, other Mediterranean cities, such as Genoa, Livorno, Marseille, Messina, and Trieste, adopted the institution and improved it: a vast, transnational system of health boards and quarantine centres was created. Quarantine stations took the form of large complexes built in main trading ports and hubs; these were generally managed by civic health boards which were in turn overseen by the central Health Magistracy of each Mediterranean state. As the health boards communicated with each other, the system of quarantine stations monitored the general state of health in the Mediterranean area, sharing news of plague outbreaks and standardizing their quarantine practices and facilities. For instance, Marseille’s health board sent approximately 250 letters per year on plague matters to other health boards, corresponding, for the vast majority, with Venice, Livorno, and Genoa.Footnote 7 Such exchange of information, knowledge, and practices ‘shaped the…Mediterranean as an integrated region socially, politically, and economically’.Footnote 8

This article sets out to make two key contributions to the history of the early modern Mediterranean: one in the debate on the relationship between Western and Central Mediterranean states and the Ottoman Empire by analysing how quarantine shaped discourses of opposition between East and West and contributed to strategies of othering by Western European states; the other in the debate on the diversity of the early modern Mediterranean presenting, for the first time, an in-depth analysis of quarantine centres as key spaces for the circulation of goods, ideas, and people, and for cross-cultural encounters. The article analyses the complexity of quarantine practices and theories which, on the one hand, seem to represent a stark contraposition between the south-eastern and the north-western shores of the Mediterranean, while, on the other hand, highlight the key role of lazzaretti as part of the infrastructure of mobility and trade. This article focuses on eighteenth-century European medical treatises and archival sources of health boards from the states of the Italian peninsula, the Venetian territories, the Austrian Littoral (Trieste), Malta, and France. It is important to note that plague preventative practices were not only a prerogative of European Western states in pre-modern times; however, this article will focus on quarantine as an almost uniquely Central and Western Mediterranean measure, and exceptions will be noted below.Footnote 9

Quarantine and its regulations relied on concepts concerning specific ideas on geographies of plague. Through an analysis of important contemporary medical works, the first section investigates how medical frameworks of contagion and plague linked the disease to specific geographies. As affirmed by Alex Chase-Levenson, plague and the strategies adopted against the disease mediated the relationship between the East and the West; Nükhet Varlık has indeed coined the term ‘epidemiological orientalism’ referring to Western European narratives on the origin of the disease in the Ottoman territories.Footnote 10 The adoption of permanent and preventative institutions such as quarantine centres was based on the idea of a perpetually ‘diseased’ Levant as opposed to the ‘healthy’ West, and I argue for the importance of early modern medical quarantine practices in shaping the later nineteenth-century definition of the Levant as ‘diseased’: a definition made by Europeans in reference both to the Ottomans’ alleged inability to control plague and to their political backwardness.Footnote 11 By examining the quarantine regulations and the use of health passes, this article analyses the pivotal role of ideas linked to diseased landscapes, provenance, and geography in determining the length of quarantine and in impacting the wider circulation of people and goods in the Mediterranean area.

This article also brings much-needed nuance to the historiographical debates surrounding the Mediterranean. In contrast to studies that have emphasized the opposition between East and West, this article embraces a definition of the Mediterranean characterized by ‘unity in diversity’ as advocated by historians such as Peregrine Horden and Nicholas Purcell, David Abulafia, and Eric Dursteler among others.Footnote 12 By focusing on quarantine, I aim to contribute to the scholarship analysing ‘(dis)connections’ and the Mediterranean as a complex concept in which unity, diversity, encounters, and clashes can be analysed as part of a whole.Footnote 13 Quarantine practices and lazzaretti are an exemplary case-study in order to present a more complex history of the Mediterranean: while the first part of this article focuses on quarantine and its role in the opposition between specific geographical and cultural areas, the second part of the article argues for the study of lazzaretti as cross-cultural spaces which allowed exchange and circulation and where different people, religions, cultures, and languages met. However, it is also my intention to frame encounter and connection as both positive and negative: as analysed below, quarantine centres displayed a degree of tolerance towards the ‘other’, but were, nonetheless, institutions that demarcated the passage between two cultural areas which were perceived as opposed: East and West. Quarantine, with its stress on isolation, fear of the other, and opposition on one side, and mobility, trade, and circulation on the other, summarizes the complexity of the region. The Mediterranean area was a multifaceted shared space as it was the backdrop to both encounters and clashes. By analysing the position of lazzaretti on borderlands and their role within flows and networks between the south-eastern and north-western shores of the Mediterranean, the study of quarantine centres contributes to the recent flourishing scholarship on the complexity of the connected Mediterranean. This article shows that closure and openness can indeed co-exist within the same institution and within the shared space of the early modern Mediterranean.

II

In a report on the Venetian public health system dated 1721 and sent to the Danish authorities by the Venetian health magistrate, Bernardino Leone Montanari affirmed that the role of the Health Magistracy was to safeguard public health from threats emerging both inside and outside the Republic.Footnote 14 Quarantine stations were thus part of those institutions adopted as a necessary precaution against dangers coming from outside the borders, from regions which were occasionally hit by plague, but more importantly the Ottoman territories. The Western European idea of a weak and plagued Ottoman Empire is well known and has been analysed most consistently in the context of nineteenth-century political discourses.Footnote 15 In this period, the Ottoman Empire was commonly labelled the ‘sick man of Europe’ by Western European states, a description that sought to represent both the state of health of the empire and, most importantly, the perceived political decadence and backwardness of the region.Footnote 16 The origins of this definition have been reconnected to early modern theories about plague by several authors including Alex Chase-Levenson and Lori Jones.Footnote 17 The contrast between the ‘healthy’ West and the ‘sick’ Levant was rooted in early modern medical theories on plague and contagion; I argue here that this opposition was reinforced by quarantine practices adopted for centuries by Mediterranean states.

During the early modern period, both cultural reasons and medical theories informed Western European perceptions of the Levant as ‘diseased’ and the consequent adoption of quarantine: first, experience and observation led health authorities and doctors to believe that plague often originated in the east and moved westward; secondly, medical knowledge attributed the occurrence of plague to specific types of environments and weather conditions, such as those of the hot and humid climate of the eastern and southern part of the Mediterranean. It is possible to find references to the dangers posed by southern climates already in Antiquity, especially in the Hippocratic treatise Airs, waters and places (c. 460 – c. 370 BC).Footnote 18 Theories of contagion and plague linked the occurrence of the disease to the quality of the air and the presence of miasma and foul odours derived from decaying matter. Consequently, the humidity and heat of the Eastern Mediterranean, which would facilitate putrefaction, were considered especially unsafe.

Treatises published during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries emphasize the dangers posed by the plagued Levant territories coinciding with the rise in Western European negative attitudes towards the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 19 Such works constructed ideas which opposed East and West in medical terms, constituting a form of medical othering; despite both Ottoman and Western European medical tradition on plague and contagion being based on the same humoral and galenic principles, Western European intellectuals underlined and shaped the differences between East and West.Footnote 20 The English physician Richard Mead in A short discourse concerning pestilential contagion, commissioned by the British privy council when the plague occurred in Marseille in 1720, affirmed that ‘plagues seem to be of the growth of the eastern and southern parts of the world, and to be transmitted from them into colder climate by the way of commerce’.Footnote 21 He also added that ‘Turkey is almost a perpetual seminary of plague.’Footnote 22 Mead was here referring to the Italian intellectual Lodovico Antonio Muratori who wrote in 1714 that ‘above all the states under Turkish rule,…are a perpetual seminary of plague…and any trade is always dangerous with those countries’.Footnote 23 As I have analysed elsewhere, plague was indeed believed to be mostly transported to Western Europe from Ottoman lands through traded goods.Footnote 24

Eighteenth-century medical theories established a clear hierarchy between the plagued Levant and Western Europe in relation to the origin of the disease: while north-western European states could be infected by the disease, it was considered improbable for plague to originate in ‘healthy’ Western Europe. This attitude was also probably exacerbated by a series of plague outbreaks that hit Northern and Central Europe (1708–13), Eastern Europe (1738), Russia (1770–2), and the Mediterranean (most notably Marseille and Provence in 1720 and Messina in 1743).Footnote 25 The Danish request for the above-mentioned report written by Montanari and its collation was probably caused by the plague of Provence that lasted from 1720 to 1722. The French outbreak indeed greatly contributed to reinforcing the idea of foreign, and especially Ottoman, faults in exporting the disease as contemporary sources considered the Grand Saint-Antoine, a ship coming from Syria to Marseille, as the culprit for the epidemic.Footnote 26 Mead indeed described the movement of the plague from east to west while analysing the Black Death in 1348: originating in Asia, it moved from China to Syria, Turkey, Egypt, Greece, and Africa, and it was finally carried from the Levant to the Italian peninsula; from there, it spread to the rest of Europe.Footnote 27 The same pattern was reconstructed by Muratori while speaking of more recent outbreaks in the late seventeenth century and early eighteenth century. He wrote:

The most recent plagues of Italy and Europe spread either due to someone’s negligence from Africa to the Christians Islands of the Mediterranean and then entered the continent. Or, coming from the Orient penetrating inside Hungary, Dalmatia, Poland and other borderlands with the Turk, it afflicted other parts of our Europe.Footnote 28

In the Encyclopédie (1751–2), Louis de Jaucourt categorically wrote that ‘plague comes to us from Asia…and none of our plagues had any other source’.Footnote 29 In his report on quarantine stations, the secretary of the health board in Marseille, J. Cezan, used a similarly categorical tone: ‘It is well known, proven and established that the plague does not originate in Europe.’Footnote 30 This hierarchy is also evident in the distinction between ‘true plague’ and ‘pestilential fever’ often drawn by early modern authors and medical authorities. True plague (vera peste), according to Giovanni Filippo Ingrassia, who wrote his treatise after the plague in Palermo in 1575–6, originated in the hot climes of Turkey, Syria, and Morea and it was more contagious than pestilential fever (febbre pestilenziale). Pestilential fever, common in the Western European context, was described as very similar to the true plague but was considered significantly less contagious and harmful to public health.Footnote 31 Thus, Central and Western European medical knowledge and cultures established a clear distinction between the Northern and Western areas of Europe in which ‘true plague’ seldom originated, and the south-eastern Mediterranean where the disease reportedly saw its origin. Notions and practical ways of dealing with the plague, thus, had become tools of othering in the eighteenth-century Mediterranean.

The Levantine origin of several Mediterranean and European pre-modern outbreaks has been widely accepted by the historiography which has taken for granted the ‘origin story’ of several plagues, such as the one of the Grand Saint-Antoine in Marseille.Footnote 32 As underlined recently by Nükhet Varlık, Lori Jones, and Cindy Ermus, scientific research on ancient DNA from plague burials has, however, confirmed that there were plague reservoirs in Europe which might well have been the sources of several outbreaks in the early modern period.Footnote 33 More research on the origin of many plague outbreaks is indeed needed to rebalance not only pre-modern ideas on the Ottoman Empire and the southern parts of the Mediterranean but also those presented by scholars.

Another source of contempt towards the Levant arose from the Ottoman alleged refusal to adopt specific preventative practices against the plague. Muratori emphasized that in ‘Constantinople and in other Cities of the Turk…disinfections are bestially disliked and neglected’.Footnote 34 Quarantine was then adopted, as affirmed by Montanari, to protect Western European states following the motto ‘guard yourself against those who do not guard themselves’, in this case the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 35 The absence of preventative practices in Ottoman lands was frequently framed as a religious opposition between ‘healthy’ Christendom and the ‘diseased’ lands ruled by the people of non-Christian belief. It was often argued that Muslim countries’ belief in predestination and fatalism played an important role in discouraging the adoption of quarantine due to debates about its religious legitimacy.Footnote 36 According to the fatalist position, plague was considered as sent by God and any measure undertaken against it would have been considered against God’s will. The Muslim approach to plague was seen as especially despicable by Western and Central European early modern authors such as Muratori who compared the Christian and Muslim positions, affirming that ‘the Turk does not provide against the plague even if it is possible. The Christian worships God and Saints but he does not believe in fate or destiny. Divine Providence does not take men’s freedom away over their business and the care for earthly life.’Footnote 37 Alexander Russell, the chief medical figure in Aleppo from 1740 to 1754, wrote that

The Turks have less faith in medicine for the cure of this disease than of any other, believing it to be a curse inflicted by God Almighty for the sins of the people…the greatest part of those who are seized with the plague, either are left to struggle with the violence of the disorder without any assistance, or must submit to the direction of the meanest and most ignorant of mankind.Footnote 38

Conversely, Montanari captures the Christian attitude by writing that ‘the health of the people is the first care assigned by God to governments and rulers’.Footnote 39

Pre-modern Central and Western European authors attributed the concept of fatalism universally to ‘Turks’ and those under Ottoman rule. However, research has shown that there was no consensus on the legitimacy of fatalism and predestination in the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 40 According to Birsen Bulmuş, the religious debate on predestination, not only concerning plague and quarantine, had a long tradition and was very dynamic with factions supporting more proactive approaches.Footnote 41 Moreover, ideas of predestination and the refusal to adopt plague-preventative measures were not the prerogatives only of Muslim countries; in England too, some Protestant factions contested quarantine measures.Footnote 42 Research has also cast doubt on Western Europeans’ statements on the Ottoman ability to fight the disease: Nükhet Varlık has pointed to the public health system developed by the Ottoman Empire in the sixteenth century precisely to combat plague outbreaks.Footnote 43 Salvatore Speziale has argued that quarantine was indeed adopted in North Africa during the eighteenth century.Footnote 44 The regency of Tunis had two quarantine sites: a small island close to the port of La Goulette and a proper lazzaretto where quarantine was implemented to high standards in the port of Ghar-el Melh. However, quarantine and its enforcement in these Ottoman areas were not co-ordinated and were often left to the initiative of local rulers.Footnote 45 The presence of quarantine stations was probably not enough to reassure the rest of the Mediterranean due to the absence of co-ordination combined with a lack of access to transnational communications on plague-related news.

Despite research showing that Ottoman theological debates on plague and preventative measures were more nuanced than contemporary Western European sources, negative connotations of the Levant linked to plague had long-lasting repercussions. The fact that quarantine was only adopted systematically in all the Ottoman territories in 1838 contributed to shaping the label of the ‘sick man of Europe’. Even after the adoption of quarantine, the previous long absence of systematic preventative practices was still seen by Western European eyes as a measure of the political inability and backwardness of the Ottoman state.Footnote 46 This section has shown that discourses on plague indeed shaped the perception of the Ottoman Empire and framed strategies of othering through medical principles as seen in Western European medical authorities and intellectuals. The following section moves to analyse how these discourses were translated into practice. The Western European perception of the Levant as a diseased land was most importantly stressed and reinforced by quarantine regulations: these controls had been adopted for centuries against goods and people arriving from the Ottoman Empire in key Mediterranean ports and trading hubs. In the next part of this article, I focus on quarantine regulations applied to passengers and goods, and on the role of geography in determining the need for and the length of quarantine.

III

Geographical notions of provenance for goods and people were essential in quarantine matters: as seen above, the presence of plague and its dangers was established according to specific geographies which contraposed the north-western and the south-eastern parts of the Mediterranean. According to quarantine regulations, which were generally uniform among different Mediterranean health boards, passengers and goods arriving from Ottoman lands (including the Barbary Coast) were always subject to quarantine; most often, they were also subject to longer periods of isolation compared to other areas of origin believed to be generally healthy. The provenance and the consequent degree of danger posed by people and goods arriving in Mediterranean ports were established by using health passes: standardized printed forms (more rarely handwritten notes) filled in by hand and issued by civic health boards or, in the Ottoman lands, by consuls of specific nations; they could be released to single travellers or the captain of a ship as a combined certificate for crews, passengers, and cargoes, or for goods only.Footnote 47

Depending on the provenance or journey declared on the health pass, it was possible to distinguish three categories of passes: clean bill of health (patente netta or libera) when the place of provenance and its neighbouring regions were declared healthy; suspected health pass (patente sospetta or tocca) when the place of origin was healthy but the neighbouring areas were not deemed so or if there were reasons to suspect a plague outbreak (e.g. a plague-infected ship was known to have stopped in the port); and foul health pass (patente brutta) when the place of origin was known to be infected with plague.Footnote 48 While the categorization of health passes was influenced by contemporary ideas that linked the Levant to plague, as shown below, this does not mean that non-Ottoman lands were considered always healthy: health offices of different states and ports constantly monitored the state of health of the Mediterranean and exchanged news of plague abroad to adjust the length of quarantine depending on which countries were flagged. Furthermore, as discussed below, the notions linked to the geography of disease analysed in the first part of this article are further complicated when considering borderlands, for instance, the Balkan area, or specific non-Ottoman territories with unregulated contact with Ottoman lands.

When a ship arrived at a Central Western European port, or a caravan into a city, the provenance of people and cargo was ascertained through the health passes which were also used to determine the length of quarantine. If the health pass was declared clean and there was no further troubling news, no quarantine was required. However, for ships, caravans, and cargoes arriving from the Ottoman Levant, the Barbary Coast, and nearby areas, a mandatory quarantine period was always enforced, even while carrying a clean bill of health and in the absence of any reports regarding plague outbreaks. For instance, Venetian authorities always considered Ottoman lands to be potentially infected and forty days of quarantine were usually applied.Footnote 49 In Livorno, ships coming from the Ottoman Levant and the Barbary Coast with a clean health pass were quarantined for thirty days, those with a suspect health pass for thirty-five days, and those with a foul health pass for forty days after fifteen days of airing susceptible goods on the ship.Footnote 50 In Messina, ships coming from the Ottoman Empire with a clean health pass were considered suspect anyway and had to undergo twenty days of quarantine and forty days of disinfection for goods considered especially susceptible to contagion.Footnote 51 Infected ships, on the other hand, were always rejected as the Messinese lazzaretto could only quarantine clean ships from the Levant.

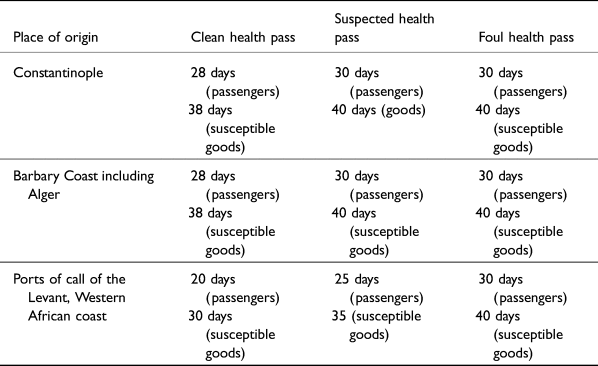

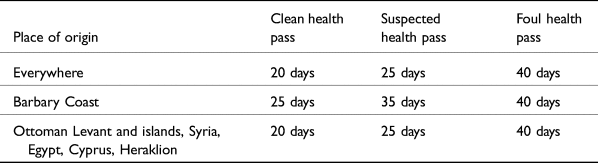

Other health boards, however, differentiated between areas of the Ottoman Empire, for instance as seen in Table 1 for Marseille. The length of quarantine could also vary depending on how far away the port of origin was; as Table 2 shows in the case of Malta, ships coming from the Barbary Coast with a clean and suspect health pass were subject to a longer quarantine just because they were closer to the island. The time spent already in isolation at sea during the travel would have been far less than for ships coming from ports further away.

Table 1. Quarantine duration in Marseille, from Memoire sur le bureau de la santé de Marseille et sur les regles qu’on y observe (Marseille, 1753), p. 41; translation by the author.

Table 2. Quarantine duration in Malta, from National Library of Malta, Archivio dell’Ordine di Malta, Arch. 274, fo. 100r–v; translation by the author.

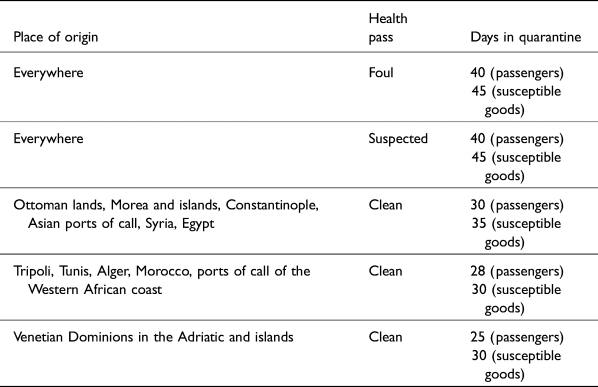

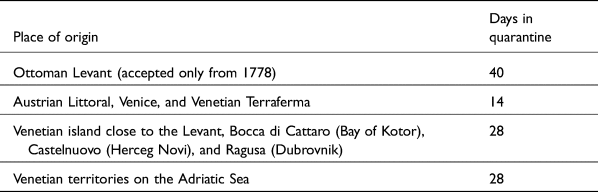

It would be wrong to think that quarantine regulations established a clear-cut demarcation between plague territories (the Ottoman Empire) and non-plague territories (the rest of the Mediterranean). There were different degrees of danger which are clear in quarantine regulations, and these include also non-Ottoman territories. Regions neighbouring Ottoman lands were also considered dangerous, and regions close to declared infected places were also further affected by harsher quarantine rules. Venice would not accept without quarantine any person, product, or animal coming from states that bordered or traded directly with the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 52 Messina, where ships with a foul pass were not allowed, would not accept without quarantine any ship from Venetian islands in the Ionian Sea and would decide according to the news of plague and the regulations established in the lazzaretti of Malta, Livorno, and Venice (which were equipped to accept foul health passes).Footnote 53 In the 1760 regulations established in Genoa, summarized in Table 3, the Venetian territories were included along with a very careful differentiation of areas of provenance. Naples which, like Messina, could only allow ships with a clean and suspect health pass, in 1778 prescribed the following quarantines, also including the Habsburg Austrian Littoral, Venetian territories, and the Balkan peninsula, all regions sharing a border with the Ottoman Empire (Table 4).

Table 3. Quarantine duration in Genoa, from Biblioteca Civica Attilio Hortis di Trieste, Raccolta Patria, Sanità Marittima, R.P. 6–133; translation by the author.

Table 4. Quarantine duration in Naples, from Archivio di Stato di Firenze, Segreteria di Stato, Affari di Sanità, 26, Affare 87; translation by the author.

There were also complex rules set by the geographical proximity to Ottoman regions and infected places. Naples and Messina carefully established a ‘safety’ distance from Ottoman lands for cargoes and passengers accepted in the port. Messina only allowed ships coming from ports at a distance of no less than 100 miles from infected places (including the Ottoman territories). Similarly, Naples accepted Greek ships with a clean health pass and without susceptible goods only if they originated from at least 170 miles from suspected and infected places.Footnote 54 The relevance of geography in determining quarantine practices is also proven by the presence of updated and precise geographical maps and geographical dictionaries usually held in health board offices: in Messina, they were often used when ships arrived in the port to interpret health passes and to check if the plague was occurring in nearby regions.Footnote 55

Areas that were distant from Ottoman territories but had unregulated contact with suspected regions were also considered dangerous. For example, ships arriving from Gibraltar or Spanish ports were deemed suspicious as they traded freely with the African coast. In Genoa and Naples, Spanish ships had to undergo quarantine for twenty days (twenty-five for goods) and fourteen days respectively.Footnote 56 Even ports beyond the Strait of Gibraltar, such as those in English territories and Flanders, were always subject to a few days of precautionary quarantine as they did not have permanent quarantine measures in place.Footnote 57

As seen in Tables 1–4, territories close to borderlands, such as the Habsburg–Ottoman border and the Venetian territories on the Adriatic (Istria and Dalmatia) and Ionian Seas, were seen as particularly dangerous. The Balkan area, divided between Venetian, Habsburg, and Ottoman rule, was conceptualized through discourses of alterity linked to its liminality as a border area which is also evident in quarantine regulations as seen in Table 4.Footnote 58 This further complicates clear-cut distinctions of East and West as contraposed cultural and geographical entities when analysing plague. While it can be argued that the presence of quarantine centres reaffirmed the role of borders as divisive lines, I also maintain that lazzaretti played a key role in enabling trading activities and travel despite the threat posed by plague. The (potential) contact with the disease in liminal areas was mediated and resolved through the use of a preventative system of lazzaretti. The Venetian Republic and Habsburg Monarchy had sophisticated preventative systems in place on the borders with the Ottoman territories.Footnote 59 Moreover, Venice’s infrastructure of control was not only situated on the Ottoman border but also the mainland, protecting the Venetian Republic from north and south. Goods and passengers coming from the Tyrolese border were also seen as potentially infected as they came from Habsburg territories which shared a border with Ottoman lands.Footnote 60 The lazzaretto in Pontebba in Friuli was used to regulate and disinfect the goods and quarantine passengers coming from Habsburg territories.Footnote 61 The lazzaretto of Verona and the separate disinfection site (Sborro) in the city were used mostly to quarantine and disinfect passengers and goods coming from the Tyrolese border through the Brenner Pass and were then directed south to Venice or the rest of the Italian peninsula.

We see the establishment of lazzaretti not only on borderlands but also in other important ports of the Mediterranean where trade with the Levant flourished: Ancona, the key port of the Papal State on the Adriatic Sea, had a lazzaretto which protected the whole Papal State (with another quarantine site in Civitavecchia). A new impressive pentagonal lazzaretto was built in the city after the declaration of the free port in 1732. As the free port aimed at increasing international trade (especially from the Levant), the new lazzaretto was essential to handle the quarantine of people and goods on the move from the opposite shore of the Adriatic, especially in July on the occasion of the famous fair of Senigallia, not far from Ancona.Footnote 62 In the rest of the Mediterranean, other lazzaretti were also founded to protect their respective states from frequent contact with ships coming from the Ottoman Empire: the lazzaretto in Messina protected the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily from trade with the Levant, exactly as Trieste assured the safety of the Austrian Littoral and the Habsburg territories; Marseille was the only French port allowed to trade with the Levant and its lazzaretto was essential in protecting the whole of France.Footnote 63

Lazzaretti did not only serve the specific state or city in which they were built but they had a transnational remit. Lazzaretti were a key part of the infrastructure of mobility within a shared Mediterranean context and also a broader European one. Cezan’s report mentioned above specified that the lazzaretti of Varignano and Livorno would protect respectively the Genoese Republic and Tuscany but were also preferred as quarantine stations by northern nations trading with the Levant.Footnote 64 Ships would stop in those ports to quarantine their cargoes and sell part of it before resuming their travels to Northern Europe. Quarantine indeed protected the whole Western and Central European continent while allowing the much desired but feared trading flows from the Levant. The next section of this article proposes to analyse quarantine centres as key spaces of trade and mobility in the Mediterranean and to unveil the cross-cultural encounters of which quarantine centres were the backdrop.

IV

Lazzaretti are here compared to other spaces of the infrastructure of travel which have recently been subject of works by historians of early modern mobility.Footnote 65 Even if seldomly analysed this way by scholars, lazzaretti were among the measures and numerous checkpoints that early modern travellers and their cargo would have encountered while travelling towards their destination, such as caravanserai, inns, and city gates.Footnote 66 Quarantine centres demarcated the passage between the outside and the inside of borders and cities, and the communication between the Ottoman Levant and the Central and Western Mediterranean. Such spaces also reflected the diversity and cross-cultural environment of borderlands, port cities, and trading hubs. A plurality of communities and ethnic and religious diversity characterized port cities reflecting once again the connections and trading activities between specific areas of the Mediterranean. For instance, the city of Ancona was populated throughout the early modern period by different communities and nations linked with the trade in the Adriatic, such as Jews and Greeks, and saw the regular movement of Ottoman subjects.Footnote 67 This diversity was reflected inside the city’s quarantine centre: the fresco depicted in Palazzo Benincasa in Ancona by Giuseppe Pallavicini in 1788 represents and celebrates the myriad nationalities inside the lazzaretto: it is possible to see sketched figures dressed in a variety of ways, especially in the Ottoman manner, and also two seated figures in black that are probably Greek Orthodox priests (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Giuseppe Pallavicini, fresco in Palazzo Benincasa showing the courtyard of the lazzaretto, Ancona, 1788. Photograph by the author.

The diversity of quarantine centres is directly mentioned in the regulations. The lazzaretto of Livorno had a specific rule on religious tolerance, for example, reflecting those adopted in the city for its communities: ‘None of the passengers, and other people, will be bothered in the exercise of their religious freedom, and rites, as long as no one will disturb nor cause embarrassment to others of different religion, and that their religious rites are carried out in their own rooms.’Footnote 68 Livorno was a popular port for many nations and, as mentioned above, was especially important for the states from Northern Europe that would choose either the lazzaretti of the Tuscan city or Genoa. Livorno was also a haven for the Jewish community as they were granted privileges not available elsewhere in Europe.Footnote 69 Christian non-Catholic minorities, such as Anglicans and Greek Orthodox, were also tolerated and the city was also known for the market of Muslim slaves and the bagno, where captives were kept.Footnote 70 The presence of non-Catholic cemeteries inside lazzaretti is further proof of the religious diversity of the passengers that happened to die in there. The lazzaretto of San Leopoldo in Livorno provided separate burial grounds for Jews, Muslims, Catholics, and Protestants (Eterodossi).Footnote 71 The lazzaretto in Malta likewise had dedicated cemeteries for Catholic, Protestant, and Muslim passengers.Footnote 72 In Genoa – after Livorno, the Italian port most frequented by Northern Europeans – the lazzaretto della Foce included a Protestant burial ground.Footnote 73 The eighteenth-century project for the new lazzaretto in Messina (never built), included two burial grounds, one for Catholics and the other for Protestant passengers.Footnote 74

While some form of tolerance might have been shown toward different religions, the time in quarantine was marked by Christian religious rites, most often Catholic. However, a small degree of tolerance was shown, and exceptions were made in the Venetian lazzaretto of Zante which had both a Catholic and a ‘Greek’ (Orthodox) church, and the lazzaretto of Cephalonia which had an Orthodox chaplain.Footnote 75 Upon requests, Christian passengers inside Mediterranean lazzaretti were usually granted the presence of a priest able to understand them or professing another confession. In the Lazzaretto Nuovo in Venice, the presence of a chaplain able to speak both Italian and the lingua Illirica (a Slavic language spoken in the Balkan peninsula) was required to minister to the soldiers who were often quarantined there.Footnote 76 In the lazzaretto of San Pancrazio in Verona, where travellers, merchants, and sometimes soldiers from German lands and the Habsburg territories in the east were commonly quarantined, there were often requests to provide priests speaking specific languages and professing different branches of the Christian faith. Different letters reported requests for Orthodox confessors and German- and Hungarian-speaking priests.Footnote 77

The issue of confession and pastoral care highlights that the lazzaretto was surely a multilingual environment, resonating with different idioms and languages. Given the oral dimension of language learning and use in the early modern period, the references found in the primary sources provide only a glimpse of the different languages that animated the quarantine stations across the Mediterranean.Footnote 78 The documents pertaining to quarantine matters can only provide the administrative point of view, reporting, for the vast majority, the staff’s need to understand passengers and not the opposite. Quarantine staff’s ability to speak other languages was particularly praised and sought after inside the lazzaretti. Understanding incoming passengers was essential when dealing with the delicate matter of contagion: precise questions needed to be asked to establish whether a ship could be a potential threat to public health. For these reasons, until the first half of the eighteenth century, the supervisor of the lazzaretto of Ragusa (Dubrovnik) was often chosen from the dragomans, as their linguistic ability and knowledge of the Ottoman culture were essential in managing a lazzaretto in an area bordering Ottoman territory.Footnote 79 Ottoman Turkish- or Slavic-speaking staff was seen as especially necessary also at the lazzaretto of Split where Bosnian merchants, who usually spoke only Slavic and Ottoman Turkish, were quarantined. Split, like Ragusa, was very close to the Ottoman borders from which weekly caravans would arrive and the presence of Ottoman subjects among passengers was prominent. The staff’s ability to speak Ottoman Turkish was praised also because it made them likeable among Ottoman passengers.Footnote 80 For the lazzaretto of Zante, the regulations recommended the election of a local prior and local staff or of subjects able to speak Greek.Footnote 81 In Genoa, the health office had a specific position for an interpreter ‘with sufficient ability, both in speaking and in writing, in the languages of the northern nations, especially English, Dutch, Swedish and Danish’, those northern nations, as underlined above, that more frequently would have chosen Genoa as a quarantine port.Footnote 82 Similarly, in Ancona and Messina interpreters were used in the arrival procedures. In the case of Ancona, this was required especially for Ottoman ships if none on board could speak Italian.Footnote 83 In Messina, the consul of a specific nation could be used as an interpreter upon arrival when the captains were not able to understand the questions.Footnote 84

The average quarantine passenger – merchants, sailors, captains, as well as the staff of lazzaretti – probably could make themselves understood without interpreters by using lingua franca, other common languages such as Italian, or a mixture of both.Footnote 85 Eric Dursteler has pointed out that, while interpreters were common in the early modern Mediterranean, multilingualism was far more common.Footnote 86 This is partially confirmed by sources: in the Genoese lazzaretto of Varignano, the report of the interrogation taken at the arrival of the Norwegian Captain Job Ossington stated that he replied in Italian.Footnote 87 In the absence of detailed sources, the traces left on the quarantine buildings also provide further proof of its multilingual environment. The passengers’ rooms of the lazzaretto of San Pancrazio in Verona (now in ruins) were covered in inscriptions in Italian, Latin, and German.Footnote 88 The two lazzaretti in Venice still have traces of writings on their walls, especially in the warehouses where there are several parietal writings in different Italian dialects, Ottoman Turkish, and Hebrew, mostly dated between the sixteenth and the end of the seventeenth centuries.Footnote 89

As seen through an analysis of the passengers, religions, and languages present inside the lazzaretto, quarantine was applied to merchants, sailors, and travellers coming from all over Europe. It would be wrong to think that, given Western European ideas on plague in Ottoman territories, quarantine was applied only to Ottoman citizens and Ottoman ships. While the regulations analysed above surely reinforced the idea of a ‘diseased’ Levant, a stereotype concerning the ‘plagued Turk’ was not the consequence and this underlines the differences between pre-modern quarantine practices and modern ones. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the element determining quarantine would indeed shift from suspicious places to suspicious people including their ethnic and social status.Footnote 90 Eighteenth-century quarantine regulations were not yet based on issues of social status or ethnicity, and any ship, traveller, and cargo coming from suspected or infected territories were subject to the same quarantine rules. While for goods, information on their origin was essential in determining the necessity for quarantine and the length, for passengers, the fundamental aspect was not the birthplace, the nationality, or the social status, but the port or place of departure and any other port or destination touched during the journey and their state of health. This was imperative and inflexible rules were applied to Ottoman and European passengers, from ambassadors to sailors, and even to nobility as well as royalty: for instance, when travelling through Italy in 1739, the grand duke and duchess of Lorraine and Tuscany (and later Holy Roman emperor and empress) Francis I and Maria Theresa had to be quarantined in Verona (not in the lazzaretto itself but in more apt quarters nearby). All the requests for a shorter period of isolation were denied, while the Veronese Health Office underlined ‘since the Lord God has not favoured Princes and exempted them from being subject to contract the plague…they should not be surprised…that they have to follow the laws of public health, which are sovereign laws for all Princes in any place’.Footnote 91 The grand duke and duchess were indeed travelling through the Habsburg territories and outbreaks were reported in the territories between the rivers Danube and Sava.

While the lazzaretto can be characterized by cross-cultural encounters, a degree of tolerance, and its diversity in terms of social status, we should not fall into the trap of considering it a multicultural and cosmopolitan space of mutual respect. As underlined above, Ottoman subjects were not targeted by quarantine regulations because of their birthplace. However, the complex cultural ideas on the ‘diseased’ Levant and the lack of preventative measures were oftentimes reflected in the relationship between staff and Ottoman passengers. Some accounts underline the contempt of quarantine staff towards Ottoman subjects, which was surely influenced by mutual dislike but also by Ottomans’ supposed ‘backwardness’ or carelessness in plague issues. In Ancona, for instance, Ottoman merchants coming from Dulcigno (Ulcinj) were known as ‘people accustomed to subverting the good order of the lazzaretto and to readily contravene the rigorous public health rules’.Footnote 92 As a consequence, they were required to deposit both the ship’s helm and some money before beginning the quarantine. In Split, members of the Ottoman caravans were considered especially irresponsible in matters of public health.Footnote 93 Of course, these considerations overlap with the stereotypical trope of the ‘terrible Turk’: the health board in Ancona referred generally to ‘Turks’ indiscipline and their natural inclination not to tolerate any injustice’.Footnote 94 Generally, Ottoman merchants were defined as ‘not tending to docility…but, on the contrary, to harshness’.Footnote 95 Similar remarks are also found in documents on other lazzaretti, such as Split and the Lazzaretto Nuovo in Venice.Footnote 96

While it is possible to reconstruct how Ottoman passengers were perceived by quarantine staff, it is very difficult to assess the experience of Ottoman or Levantine passengers inside the lazzaretto. Accounts of quarantine by Ottomans (and by passengers in general) are difficult to find, and usually, they pertain to ambassadors who had a very different experience of quarantine from merchants, slaves, sailors, and travellers. However, quarantine could have been seen as a foreign and interesting practice worth presenting to the audience as the sources describe in detail the procedures. The Ottoman ambassador to the French court, Yirmisekiz Çelebi Mehmed Efendi, who was quarantined in 1720 during his embassy in France, describes the purpose of quarantine in its particulars but it is also possible to see that he was annoyed about being subject to the practice as he fiercely demanded a reduction of his forty days of isolation.Footnote 97 In another instance, the Moroccan ambassador to Spain, Ibn Uthmân, was also outraged to be subjected to quarantine in Ceuta during his travels to Spain in 1779 and nonetheless explains quarantine carefully as a subject of interest. Likewise, the Ottoman traveller Evliya Çelebi, quarantined in Ragusa during his travels in 1663, described the lazzaretto as similar to a han (the Ottoman caravanserai). By doing so, he presented a familiar reference to his Ottoman readers:

Nazarete (lazaretto) is the term for the han or guesthouse where merchants and diplomats…are lodged. Generally, they must stay for forty days, in special circumstances for ten or seven or, at the very least, three days, to make sure they are not plague-ridden before they enter the city…It is a square building, very like a han, with numerous and well-outfitted rooms, one after the other, and kitchens and stables and rooms for the infidel soldiery.Footnote 98

From these accounts, it seems that, to the eyes of Ottoman passengers, the lazzaretto was probably perceived as a peculiar institution, worth to be noted with interest and with slight unfamiliarity, especially in travel writings.

We can also assume that quarantine symbolized the passage of Ottoman subjects, of different religions, into the Christian lands as it is possible to see in the writings of the Armenian traveller and Christian pilgrim Simēon of Poland. In 1611, Simēon arrived in Split and to his complete surprise was put into quarantine before boarding a ship to Venice. He was completely unaware of the procedure and his confusion was worsened by his inability to communicate with the staff of the lazzaretto who, despite their multilingualism, were not able to communicate with him but he was able to communicate with other passengers. For him, quarantine was comparable to prison. He wrote extensively on his experience and also composed a poem in which he commented on his forced isolation:

In his words, quarantine indeed took place in a ‘foreign land’. Furthermore, Simēon looked forward to being in Christian lands and quarantine marked a last hurdle before finally entering Christianity. After finally being freed from the lazzaretto, he commented:

Muslims were no longer visible and the Turkish law did not exist. Everything was Christian. Seeing all this, we became overjoyed, cheered up, revived in body and soul so that we even forgot our torments and pains on the trip and the quarantine. From here on, the rule and might of the Muslims disappeared and Christ and Christians reigned.Footnote 100

Simēon’s situation was especially peculiar because of quarantine’s total novelty for him; for sailors and merchants, however, quarantine would have been a more familiar experience. A very rare account by the Christian Arab traveller Ra’d from Aleppo, who arrived in Venice in 1665, describes carefully his quarantine with the other passengers from his ship, all the disinfection procedures and the medical inspections. The tone is very analytical and does not show much surprise for the procedures. This is consistent with the fact that he was a merchant, probably aware of the institution and potentially had other experiences inside quarantine stations. Furthermore, the quarantine procedures that he witnessed, such as fumigations and the use of vinegar to disinfect, were based on humoral and galenic theories which were in common between the Ottoman and Western European medical practices.Footnote 101 However, knowledge or familiarity of the procedures as in the case of merchants does not mean that quarantine was tolerated better. In 1754, the Lazzaretto Nuovo hosted a group of ‘Turkish’ merchants deemed troublesome by the health official. They demanded to be freed from the quarantine, affirming that ‘Turkish merchants cannot be held as slaves’, indicating that quarantine could be indeed perceived as a Western imposition on Ottoman bodies.Footnote 102 However, as we have seen, reactions to times in quarantine were different and multifaceted for travellers coming from every corner of the Mediterranean and beyond.Footnote 103 It is extremely difficult to assess the experiences of quarantine in general and these were due to a variety of factors such as social status, whether ambassadors, travellers, sailors, or merchants are taken into account. However, it is important to highlight that passengers’ ethnicity, culture, and religion surely played key roles in shaping experiences of quarantine.

V

Lazzaretti and the institution of quarantine well represent the complexity of the Mediterranean: quarantine underlined the diversity of East and West as established by Western European medical, cultural, and political notions on plague; as a shared space, quarantine centres allowed and mediated the contact between the Western and Central Mediterranean and the Ottoman lands despite plague and were populated by different peoples, cultures, languages, and religions. The Western European early modern notion of the Levant as a diseased land played a key role in the establishment of quarantine; this idea was linked to both contemporary medical thinking and cultural ideas which would shape Western European ideas of Ottomans for centuries to come. By analysing contemporary Western European medical thinkers, this article has demonstrated that both cultural and medical notions regarding the Ottoman lands played a key part in the establishment of quarantine and in constructing practices of othering. Through the examination of the regulation of quarantine, I have stressed that quarantine measures contributed to reinforcing ideas which opposed East and West. Geography was the key determinant: the regulations of quarantine were extensively linked to geography and related medical ideas but not to nationality or ethnic identity, as would happen in the nineteenth century. During the eighteenth century, the necessity for quarantine and quarantine length were determined by an established hierarchical view of the geography of plague which saw a ‘healthy’ West as opposed to a ‘plagued’ Levant.

This article has underlined that quarantine procedures were not only characterized by a stark opposition between the two sides of the sea. Lazzaretti were founded to allow and promote exchange and circulation between the Western and the Eastern Mediterranean. They were the backdrop for regular movements of people, such as seasonal workers, and were built to serve specific trading networks between European Mediterranean cities, the Levant, and the broader European continent. This study has shown that lazzaretti should be analysed along with other elements of the infrastructure of mobility, emphasizing their role as spaces of cross-cultural encounters by analysing multilingualism, the presence of different religions, and nationalities. More importantly, this article has not taken for granted the tolerance showcased by quarantine regulations which could be assumed by the presence of diverse ethnicities, languages, and religions in the quarantine space. Instead, this study has considered critically the experience of Ottoman subjects inside the lazzaretto, a space representing the transition from East to West, contributing to a more nuanced picture of the Mediterranean. This work has shown that, through the analysis of quarantine, it is possible to investigate the shared and diverse Mediterranean by including both opposition and convergence.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Mary Laven, Stefan Hanß, and Marie-Louise Leonard for their invaluable comments on the drafts of this article. An earlier version of this article also received feedback from the organizers and correspondents of the workshop ‘Mobilities in Early Modern and Contemporary Mediterranean’ organized by Roberta Biasillo, Maria Vittoria Comacchi, and Lavinia Maddaluno at the European University Institute. I am also very grateful to the reviewers for their comments and time.

Funding statement

Research for this article was possible thanks to the Cambridge Trust; Girton College Graduate and Travel Awards; the Faculty of History’s Fieldwork Fund at the University of Cambridge; the Royal Historical Society; and the Prince Consort and Thirlwall Prize and Fund.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.