Chaim Wasserman, a young Jewish man from Poland, was in a detention camp in London when the war in Europe ended. The camp authorities described him as a student, but that had been his status six years earlier, when at the age of eighteen he was sent to live in a ghetto in Warsaw, then to several prison camps, then to Auschwitz, and eventually to Buchenwald, from where he escaped in April 1945. It was then that he crossed paths with a group of liberated British prisoners of war, with whom he was evacuated to England. Why was Britain detaining a man like him? Wasserman was in fact among the last of 34,000 civilians to have passed through that camp between 1941 and 1945, most of them Allied nationals who had been evacuated or escaped to Britain. Few had been concentration camp inmates – many were volunteers for the Allied Forces, some were members of resistance groups, others were war workers. Women and children, often coming to join their husbands and fathers in the latter groups, were also detained. The purpose of their detention was for the Security Service to determine whether they were enemy spies or genuine refugees (a term used in a colloquial sense rather than to denote a specific background).

The decision to incarcerate non-enemy civilians solely for interrogation was taken over a year into the war. But it came on the back of policies that treated all foreign nationals with suspicion and sought to control their presence in the country since before war broke out.Footnote 1 While tens of thousands of Germans, Austrians, and Czechoslovaks fleeing the Nazis had escaped to Britain between 1933 and 1938, most of them Jews supported by the local Jewish community, stances changed when responsibility for refugee support was shifted onto the state. Compounding the situation was the fact that Germany launching an aggressive war would cause non-Jews to flee too, as indeed happened. The estimated numbers, together with a conviction that the presence of more Jews would exacerbate anti-Semitism in the country, led Neville Chamberlain's government to abandon plans to rescue any large numbers of people of whatever nationality once war broke out.Footnote 2 Instead, only pre-selected individuals would be granted visas based on skills shortages. Escape to Britain during the war was thus not facilitated in any large scale and not on humanitarian grounds.Footnote 3

People nevertheless did arrive, often clandestinely, and contributed both to the local and the wider war effort. Belgian refugees, for example, added substantially to the British economy and forces;Footnote 4 Norwegian officers worked closely with the British on the intelligence front;Footnote 5 while without the Polish mathematicians who developed techniques against ciphers, the ‘Ultra’ operations at Bletchley Park ‘would never have existed’.Footnote 6 What we often know about these people is evidently their part in the war effort in general, nationality-based terms.Footnote 7 An exception is Wendy Webster's transnational study of non-Britons in Britain, which drew on a range of sources to reveal a country that was more diverse during the war than at any previous point, and indeed more diverse than it is remembered today.Footnote 8 This article uses the official archive of the UK government to add to these efforts of documenting the history of multinational wartime Britain, and does so through focusing on the camp in which Wasserman was detained. The camp lends itself well to transnational examinations both because its remit cut across nationality lines and because life there was the one experience many arrivals shared: detention was compulsory, and it was only after it that they were allowed to proceed for billeting or enlistment. Put simply, the camp – based at the Royal (Victoria) Patriotic School in Wandsworth, south London – is the only window we have into the first contact wartime arrivals had with UK authorities, before they became part of British society and the war effort in the ways that Webster and others have examined.

Yet little is known about the camp's purpose and living conditions.Footnote 9 This is largely the result of a deliberate ambiguity that surrounded this place, and which later turned it into a blind spot for historical enquiry. Specifically, the Royal (Victoria) Patriotic School's (RPS) status as a detention camp was concealed during the war, with it having been presented as a ‘reception’ camp for refugees and volunteers for the Allied Forces; it was even formally known as the ‘London Reception Centre’, in an attempt to detract from its detention function (hence why this article does not adopt this latter name). Consequently, RPS has been left out of studies into British civilian internment. With the exception of some brief mentions, it has also been left out of studies on the refugee experience, since stays in RPS were themselves brief. Having been treated neither as a detention nor a refugee camp, it has nevertheless been examined as an intelligence camp: recent quantitative analysis into thousands of interrogation reports produced in RPS has revealed its value both to the three Fighting Services and several government departments.Footnote 10

Important as RPS was for such purposes, its story spans beyond intelligence history. By shifting the focus away from the information that was obtained in this camp, this article answers three questions that are of wider significance: why was the detention of non-enemy civilians considered necessary until May 1945; who exactly did it affect; and how was it managed? Seen in this broader light, the story of RPS concerns the nature of detention in wartime Britain, the status of foreign civilians, as well as the state's attitude towards them before they came to be of any obvious use to it, such as through employment. In particular, RPS demonstrates that, despite fears of a ‘fifth column’ having subsided by the end of 1940, non-Britons were viewed with suspicion throughout the war. This suspicion was, however, not uniform and was primarily the attitude of the Security Service (MI5); departments such as the Home and War Offices, as well as their camp staff on the ground, often saw refugees as war victims and allies, attitudes that were reflected in RPS's living conditions.

This plurality of attitudes muddled RPS's status as well as its legacy: was it a detention, refugee, or intelligence camp? Clearly, RPS was all three. While this was a place from which British intelligence benefited extensively, at the same time it was a temporary home for refugees, who were nevertheless kept there as detainees – even though they may have sometimes been unaware of this status, as will be explained. Indeed, Jordanna Bailkin's recent work, which has transformed the way British refugee camps ought to be understood, demonstrates how such sites resembled detention camps, even in the absence of the necessary legal footing: ultimately, their residents were very often not free.Footnote 11 The case of RPS confirms this association, showing how an actual detention camp was passed as an unremarkable reception centre. Seen in this way, and despite the fact that RPS had no obvious precedent, its existence is part of a longer history of the lines between refugee reception and detention getting blurred.

That these different functions existed under the same roof then raises the question of how the state coped with the detention of people who shared little in common – they arrived from dozens of different countries, using different means, and for different reasons. In answering it, the article reveals the bureaucracy that developed between MI5 and the Home, War, and Foreign Offices allowing them to maintain this sensitive operation until May 1945. The fact that RPS involved these various departments makes it an intrinsically important case-study of how certain intelligence efforts relied on those of external sections. This aspect is difficult to capture elsewhere, since few establishments commanded the constant attention of these multiple stakeholders – camps for the detention and interrogation of prisoners of war in Britain were primarily the domain of the War Office;Footnote 12 the camp for the detention and interrogation of spies was the domain of MI5;Footnote 13 while internment camps for civilians were the responsibility of the Home and War Offices.Footnote 14 In this sense, RPS's story also illustrates Peter Gatrell's argument, that refugee history can serve as a prism through which to understand other matters, in this case matters pertaining to British wartime attitudes and institutions.Footnote 15 To achieve this, and given the heavy involvement of these various departments in RPS, the research relies on the official record. While the latter can hinder the lived experience in places of incarceration, the involvement of intelligence has imposed limitations on the existence of non-government sources (not least because RPS was ‘the most difficult place to get into and out of’).Footnote 16 However, the paper trail left behind is not limited to administrative minutiae and propaganda: the interrogation reports produced form a unique source through which to piece together the stories and background of some of Britain's refugees.Footnote 17 The article thus uses the UK government's own archive to offer a first thorough examination of the camp's administrative evolution and purpose, highlight the stories of individuals who fled Nazi Europe, and uncover a so-far neglected site of multinational wartime Britain.

I

The mass detention of non-enemy civilians solely for interrogation was not an immediate resort when war broke out. During the ‘phoney war’, and in line with action taken during the First World War, the main focus were Germans and Austrians, and later Italians as well, who were already in Britain, some of whom were interrogated to establish their allegiances. The ideological dimension of the conflict, however, soon revealed the fact that nationality alone would not be enough to identify a true ‘enemy alien’, a term which technically referred to nationals of countries with which the UK was at war. In fact, Britons too could be interned if they were (suspected) fascists. Most foreign arrivals thus became of concern and different measures were put in place to deal with the situation. Anyone who was suspected of spying or having arrived illegally was interrogated in MI5's Camp 020, the place where the Double-Cross System was operating, ‘turning’ Axis agents into double agents. Then there were the ‘enemy’ nationals, for whom separate internment processes were put in place; in any case, few arrived after 1939.Footnote 18 Of particular relevance here is the third category: nationals of friendly and neutral countries who arrived in larger numbers after May 1940. With the invasion of the Netherlands and Belgium that spring, thousands fled to France, and Britain expected 300,000 of them to reach its shores, even though only about a tenth of such figures managed to reach the UK that summer. But despite being a fraction of what was expected, refugees arrived amidst revelations of Vidkun Quisling's involvement in the invasion of Norway, with similar rumours spreading about other places. These developments served to exacerbate an existing fear of a British ‘fifth column’, much of which was expected to arrive disguised as refugees.Footnote 19 All arrivals were thus vetted at the ports by MI5 and those whose interrogations were unsatisfactory were handed to the police.

Although the arrangements at the ports were quickly recognized as inadequate – interrogations were brief, inconsistent, and carried out by untrained personnel – they remained in place until November 1940, when a more stringent process was adopted. At that point, large-scale evacuations from Europe were being restricted, with ships only allowed to admit those with visas, ‘in order to stop at the source the movement of Alien refugees to this country’.Footnote 20 With few refugees expected to arrive from then on, the vetting process became more thorough: instead of allowing those with satisfactory port interrogations to proceed for billeting as before, they were now to be taken to London for further interrogation.

The Royal (Victoria) Patriotic School in Wandsworth – ‘one of the gloomiest specimens’ of Victorian GothicFootnote 21 – was selected to receive these apparent non-suspects from December 1940 and was officially opened the following January. Originally a boarding school for orphans of the Crimean War, turned into the South Western General Hospital during the Great War, RPS was to be receiving all men from friendly and neutral countries coming to the UK to work for the war industry or volunteer with the Allied Forces – no women, no children, no ‘enemies’. The incarceration intention behind it was clear: arrivals had to ‘be kept under physical control from the moment they set foot in this country until such time as they were cleared by the Security Service’.Footnote 22 Their status was therefore that of persons under detention, not internment, the former being the temporary detention of a suspect, the latter the preventative deprivation of liberty on security grounds (as with ‘enemy’ nationals).Footnote 23

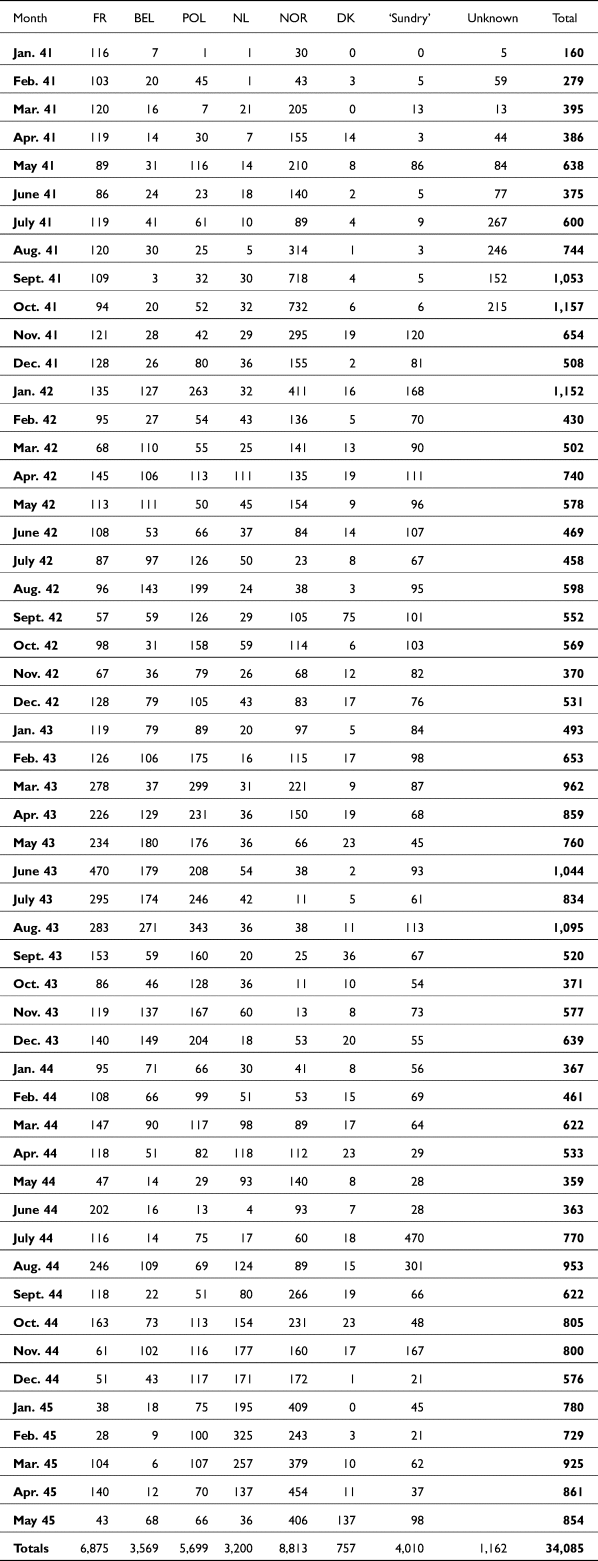

Arrangements for women were also made. Those from friendly countries who were not accompanied by a man were considered ‘potentially dangerous until thoroughly vetted’ and were detained, with any children they had, in a nearby evacuated school in Balham.Footnote 24 Despite being located in a different neighbourhood, the building – 101 Nightingale Lane – was part of the RPS establishment. Women accompanied by a man were initially exempted from detention. This policy ceased in February 1941, when it was decided that those women (and their children) had to be detained too.Footnote 25 Other categories first exempted were also included at that stage, the result of a realization within British intelligence that German espionage abilities were much less advanced than initially thought, and so the only way an agent would attempt to enter was openly, disguised as a refugee.Footnote 26 By early 1941, it was thus the ‘unimportant people’ who became prime suspects, such as women and seamen.Footnote 27 This meant that the only people not sent to RPS, bar occasional exceptions, were ‘enemy’ nationals; Allied diplomats; Britons and British subjects; Americans; Russians; and neutral aliens (unless they wanted to work for the war industry or enlist).Footnote 28 Figure 1 shows when all others passed through RPS.

Figure 1. Monthly RPS arrivals, January 1941–May 1945. Note: the full data behind the figure can be found in Appendix I.

Evidently, despite the abeyance of ‘fifth column’ fears before RPS even opened, the camp saw a constant flow of traffic until May 1945, raising the question why. Part of the answer is that while fears of a co-ordinated group working to undermine domestic security had subsided, there still remained fears that individual agents would infiltrate the Allied Forces. Britain was in a position to control this latter threat since under wartime legislation, and in certain circumstances, Allied nationals arriving in Britain were subject to conscription; moreover, joining the Allied Forces often required travelling to Britain in order to do so. The nationalities behind Figure 1 support this function of a vetting camp for future recruits. The first relative spike in arrivals occurred in mid-1941 and was driven by Norwegians, some of whom had been brought back from various British commando raids – which they assisted – starting with Operation Claymore in March.Footnote 29 The second wave came in the first half of 1943 and was driven by French nationals. Operations in North Africa in the previous months had enabled many Frenchmen abroad to enlist, but to do so they had to be evacuated to Britain. Such were the numbers involved that it was eventually agreed that such volunteers would be taken directly to Algiers, not the UK. The final, continuous period of arrivals started in mid-1944, coinciding with preparations for the liberation of Western Europe; it was accordingly driven by Norwegian and Dutch nationals.

Even so, until mid-1943, MI5 had a policy of collecting all arrivals in RPS, not just prospective recruits.Footnote 30 Accordingly, around 62 per cent of those who were detained in 1941 and 1942 went on to enlist.Footnote 31 At the end of 1943, officers at the ports were asked to continue sending prospective volunteers without exception, but only send non-volunteers if there were grounds for suspecting them.Footnote 32 This timing coincided with a broader policy of advising ‘intending refugees…to stay where they were’, due to the changing tide of the war.Footnote 33 The point when there was an attempt to restrict RPS's remit to volunteers was therefore also the point when non-volunteer arrivals were being restricted even further. The evidence thus suggests that most relevant nationality categories who arrived during the war passed through RPS.

Whatever their reasons for escaping, only a fraction of these civilians had the potential to be a threat: fewer than 300 were detained further (fewer than 1 per cent of all), fifty of whom were subsequently confirmed as agents. One of those was Johannes Dronkers, a Dutch clerk in the German Post Office in The Hague until he was recruited by the Abwehr and sent to Britain on a small boat, in order to report back on various British Army matters. His story did not convince RPS who dispatched Dronkers to MI5's Camp 020; he was convicted and hanged on the last day of 1942.Footnote 34 Notably, Dronkers had been briefed by the Abwehr about RPS, indicating that knowledge of the camp's existence may have deterred less thought-through infiltration attempts and indeed, only three agents are known to have evaded detection. Two of them were Norwegians who arrived in England for ‘whisky and Intelligence’ and fooled not only RPS but also the Norwegian Forces, which they joined; they were arrested after an intercepted German radio message revealed their mission.Footnote 35 While it may therefore be straightforward to dismiss RPS's value in preventing infiltration only by looking at the small number of known attempts made, the task is less straightforward when considering what tactics the Abwehr may have employed in the absence of this obstacle.

Yet for MI5, the question was not simply whether a refugee was an agent or an ally: some fell in between. Those were people who lied about their past or were ‘renegades of varying degree’.Footnote 36 Among the last ‘undesirables’, as these individuals were called, was a man who claimed to have been Polish but to have grown up in Greece. His story was believed, and he was sent to the Greek Mission in London, who duly returned him to RPS until confirmation of his story was received from the Greek authorities. It was upon his return to RPS that he revealed himself to be Herbert Ernst Hintz, a German farmer. The son of a communist, Hintz declared ‘that he had always been opposed to the Nazi Government’, he had not joined the Hitler Youth, and had deserted in Greece in 1941.Footnote 37 Although his account was considered ‘probably true’, the fact that Hintz claimed to have mastered the Greek language only after being shielded by locals in 1941, as well as the fact that he had initially lied about his age, saving him from having to account for five years of his life, rendered him ‘undesirable’. Such people were not kept in RPS indefinitely – they either became the responsibility of other MI5 sections, or were released to their national representatives with ‘an appropriate warning’.Footnote 38

That Hintz's interrogations took place in the spring of 1945 also points to the fact that MI5's standards in RPS were never relaxed. If anything, in the run up to D-Day they became even more inflexible: ‘until the military operation had been well and thoroughly launched no chances were taken in the way of releasing aliens against whose bona fides there remained the slightest residual doubt’.Footnote 39 Even the timing of one's arrival was subject to scrutiny during that time, leading to assumptions as to their ‘true’ motives for escaping:

The quality of the arrivals, particularly Belgian and Dutch, has deteriorated considerably. These belated ralliers to the Allied Cause can, for the most part, make no pretence of being impelled by patriotic motives, and often enough they have not made the slightest attempt to resist the enemy at home. Their motive for escaping is pure selfishness: mostly the risk of being conscripted for work in Germany has roused them to leave their homes. And furthermore, these attentistes have at least decided on which side of the fence it will be most profitable to jump.Footnote 40

Clearly, in RPS MI5's remit changed. As the Allied war effort was turning on the offensive, the focus was less on identifying enemy agents and more on gathering counterintelligence, identifying ‘renegades’, and identifying agents to recruit. The way MI5 were fulfilling these purposes also changed as a result, with more elaborate record-taking and indexing practices having been adopted: whereas in October 1941, an MI5 officer would deal with three or four detainees daily, by February 1943 that had decreased to one detainee, and it would now take more staff to complete an individual's interrogation.Footnote 41 The result was that after the war, RPS was praised within MI5 as having had ‘an important effect in altering the status of the Security Service and in rendering possible systematic intelligence work’.Footnote 42

II

Non-enemy civilians were treated with suspicion by MI5 throughout the war, not just during its first year. But while suspicions remained, the actual expectation that enemy agents would be found in RPS was never great, even within MI5. Despite this awareness, the duration of detention was increasing. The average stay in January 1941 was a day,Footnote 43 in November it was four days, and by August 1942 it had almost tripled to eleven;Footnote 44 it fell to between nine and ten days in March 1943.Footnote 45 What explains this paradox is the fact that non-enemy civilians held information that was useful both for counterespionage purposes but also military and political ones. Accordingly, together with MI5 and the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), the Directorate of Military Intelligence (DMI) set up a detachment in RPS in the summer of 1941, interrogating on behalf of several other sections, from specialist War Office and Admiralty ones to those of the BBC; the Air Ministry also attached officers there soon after. By the autumn of 1941, RPS was already ‘very rapidly changing its character’, with the majority of its work focusing on gathering intelligence, despite prolonging detention in the process.Footnote 46 For that reason, much of the official record around RPS is made up of interrogation reports, especially those of the DMI detachment, which are unrelated to espionage and are instead concerned with military and civilian matters in occupied territory. Containing information from about 4,000 detainees, this material is particularly insightful because it concerns the ‘average’ civilian rather than those who were of some security interest due to their background, like Dronkers and Hintz. Crucially, these reports are one of the only sources – if not the only one – through which to understand why and how people came to Britain, as well as through which to learn more about who they were in terms of gender and nationality.

The first key question which the reports help answer is how people reached Britain. Approximately a quarter of the detainees in the reports were fishermen and seamen who had the knowledge and means to escape; they would often bring others with them.Footnote 47 Many did so on an ad hoc basis, but others worked for the ‘Shetland Bus’ – a clandestine fleet run by MI6, the Special Operations Executive, and Norwegian military intelligence, sending supplies to Norway and bringing back refugees. It was the ‘Shetland Bus’, for example, that brought seven Norwegian men – a teacher, two commercial travellers, a fisherman, a mechanic, a medical student, and a journalist – on board the fishing boat M/K Heland M5V in February 1942.Footnote 48 The average journey to Britain nevertheless emerges from the reports as ten weeks, which means that people often made their way to neutral territory first, and were from there either evacuated to Britain or made the crossing using the more clandestine means described. Far more rarely, there were crash landings, including one on the morning of 5 July 1941 when a two-seat plane, stolen and flown by two former pilots of the Belgian Air Force, landed on a field near Harwich.Footnote 49

Escapes were not always planned. A man who found himself in England apparently coincidentally was Hermanus Corbiére. Late in the evening of 17 June 1941, twenty-year-old Corbiére saw six fellow Dutchmen trying to escape Holland on a small boat; after helping them launch it, he pretended to be drowning in order to be pulled in and escape with them.Footnote 50 He arrived the next day with the party of six strangers – a carpenter, two engineers, one of whom was on the run from the Gestapo, and a doctor with his two sons.Footnote 51 Although Corbiére may have been hoping to escape and was for that reason in the area that night, other examples of people who did not necessarily plan to come to Britain include Norwegians brought back after British raids. One of those was a tinsmith from Narvik who was on board the cargo vessel Mira when it was torpedoed in March 1941; he was wounded during the raid and brought back by the British commandos.Footnote 52

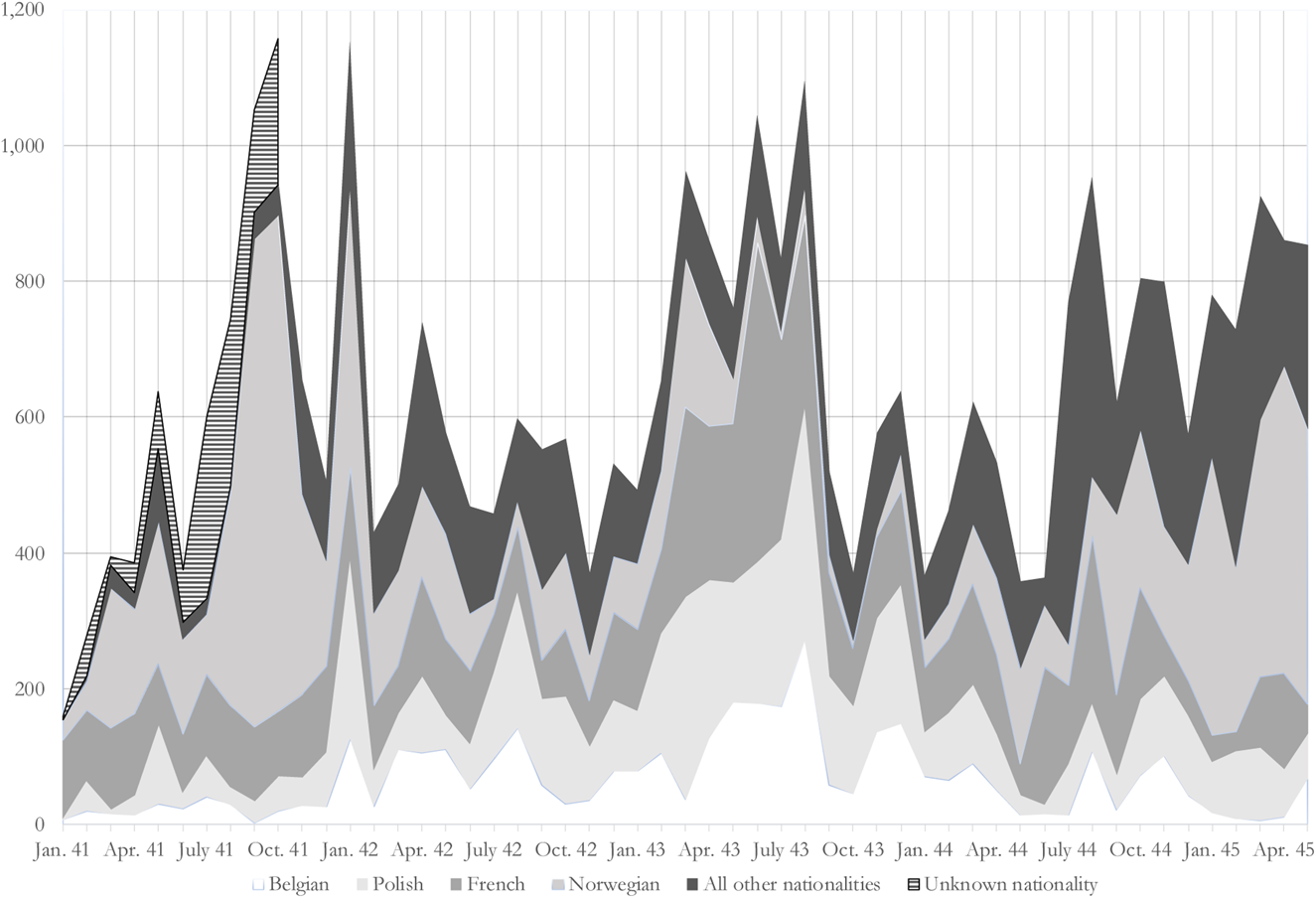

A second question these reports help answer is where did these people come from? Unlike the crude data behind Figure 1, where dozens of nationalities were classed as ‘sundry’ by MI5, the DMI reports drew on individuals from at least twenty-nine countries. The frequency with which the main nationalities appear in the reports (Figure 2) is, however, similar to the trends observed in Figure 1, with those from Western Europe dominating the reports.

Figure 2. Individuals in the reports of the DMI detachment in RPS, by nationality (N = 3,942). Note: ‘Other’ includes several nationalities, most of which appear only once in the reports.

Yet some nationalities stand out since they were normally exempt from the process, the first being Britons, the majority of whom were from the Channel Islands. One of them was a shoe shop assistant from Jersey who had been caught by the Germans listening to the BBC in 1944. Having been sentenced to deportation to Germany, he was being driven through north-west France when his bus run into a US combat group, who liberated the prisoners and shot their escorts.Footnote 53 His report discussed civilian morale in Jersey, confirming that there had been ‘very little resistance to the Germans’, and claiming that the ‘behaviour of a great number of women has been quite disgraceful’, with ‘many illegitimate children on the island born to German fathers’. The remaining fourteen pages touched on a number of other matters, from currency changes and taxation to local cinema and theatres.

But while forming the majority, not all Britons were from the Channel Islands. One was a merchant who returned home to England after living in Japan for some thirty-six years; in RPS he discussed that Allied broadcasts were being jammed – the sound was like ‘running water’ – and opined that the best time for them was after seven in the evening.Footnote 54 Another Briton – an official who left Hong Kong shortly after its surrender – discussed how the Japanese operation ‘was well planned, perfectly executed and the co-ordination of the services moved like clockwork’.Footnote 55 The report does not elaborate on his background, but the man appears to have been David Mercer MacDougall, who after the war became colonial secretary of Hong Kong and briefly its acting governor.Footnote 56 It is unclear whether any Britons were detained in RPS or were interrogated by its officers elsewhere.

A second nationality that stands out in Figure 2 is Russian, as Russians and Americans were usually exempted from RPS too. The overwhelming majority of Russians in the reports were previously forced labourers in Organisation Todt and were interrogated in July 1944; among them were two children aged twelve and fourteen, a ‘political commissar’, a peasant, railway workers, and army officers. Several Organisation Todt labourers were interrogated in RPS, not just the Russian nationals. In fact, in mid-1943, the Theatre Intelligence Section of the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force, planning the invasion of Normandy, said that ‘their knowledge of Organisation Todt in the West was largely based’ on a Belgian stevedore's account in RPS.Footnote 57

Together with former forced labourers, RPS's detainees included people who had previously been in German captivity. In 1943, for example, a Polish man brought photographs showing interned Jews in Morocco – the length of his journey nevertheless meant that Morocco had been captured by the Allies by the time he reached RPS.Footnote 58 Two years on, a French Jew found himself in RPS after being liberated from Auschwitz; with him was a Dutch Jew who had been a forced labourer, and a Polish officer who had been a prisoner of war since 1939. All were asked about their treatment by the Russians after liberation (which they said was overall correct).Footnote 59 Days later came Chaim Wasserman, mentioned earlier and described as ‘a young and intelligent Polish Jew, who fell into the clutches of the Gestapo’ in 1942, when he attempted to escape to Czechoslovakia and ended up in Auschwitz.Footnote 60 His report, discussing some of the horrific things he experienced there, was complemented by the account of a forty-nine-year-old haberdasher, also a Polish Jew. The latter described how several inmates were burned alive by the Germans as the Russian advance was approaching in 1945, while the rest were sent on a march; during it, he was injured and abandoned on the side of the road. He was found by escaped British prisoners of war who gave him a uniform and had him pretend ‘he was of Australian origin’; he stayed with them for some three months, until they were all liberated by US troops and sent to the UK.Footnote 61

Alongside victims of Nazi persecution, RPS's reports drew on Germans – the third nationality that stands out, even though it is unclear whether any were actually in RPS. Among the first was Fritz Beckhardt, interrogated in June 1941 and described as having been ‘in Goering's squadron in the last war’.Footnote 62 In reality, Beckhardt was a highly decorated fighter ace in 1914–18, he had been detained in Buchenwald in the present war because he was Jewish, and was apparently released at Hermann Goering's orders.Footnote 63 Aside from Beckhardt and a few deserters, the majority of Germans arrived after the summer of 1944 – due to difficulties in finding suitable accommodation to evacuate civilians following Allied operations, some were sent to the UK. Among them were also women who were interrogated in Holloway Prison, not RPS, including the secretary of a firm working with Organisation Todt, who was deemed to be ‘under the narcotic of many years of Nazi propaganda’.Footnote 64 She was followed by the ‘rather attractive’ wife of an officer twenty years her senior; although she was thought to be anti-Nazi, she was ‘unfortunately of the pampered wife type, not over intelligent’.Footnote 65

Remarks such as the above, together with the small number of reports concerning women, point towards the fact that less importance was placed on the value of women as intelligence sources, even though some of the information was followed up. For example, a French woman, previously a driver for the Red Cross, reached England via Spain and gave information that led to a building in France being put under Allied watch as a potential German parachutist school.Footnote 66 Moreover, while approximately 1 per cent of the reports were by women, the overall number of women who reached Britain during the war may have been much smaller than that of men (unlike before 1939, when the majority of refugees were women and children).Footnote 67 Although regular statistics have not been located, between January and June 1942, Nightingale Lane had 403 detainees, 141 of them children.Footnote 68 Those same six months saw around 3,300 men stay in RPS – eight times Nightingale Lane's traffic. The majority of the women and children during that period were Norwegian (53 per cent), most of whom had been evacuated to Britain following raids. Then there were Belgian women and their children (11 per cent), most of whom were wives of volunteers or workers; the same went for Polish detainees (9 per cent). As for the French (also 9 per cent), half were wives of serving members or volunteers, while the rest were themselves volunteers for the Women's Auxiliary Service or the war industry.

The smaller number of Nightingale Lane detainees has affected the volume of material available for that camp. Much of it concerns train sets, toy trucks, bath toys, and dolls: one of the main expenditures for Nightingale Lane was on toys, since the children would often break them or refuse to leave them behind. But toys were not one of the areas that the Home Office wished to save money over: ‘it would be hard hearted to deprive the kiddies of any small toys, to which they had become attached, when the time came for them to be moved on’.Footnote 69 Discussions over Nightingale Lane actually reveal another way in which refugees were seen, particularly by camp staff: as victims of war. As soon as it was announced that Nightingale Lane would start accommodating German women in 1945, its deputy commandant handed in her resignation, because she felt ‘it would be quite impossible for her to combine the two jobs of looking after friendly aliens and enemy aliens’.Footnote 70 (She was forced to withdraw it for there was no one to replace her.) Similar attitudes existed among staff in the men's camp. The first commandant of RPS, for instance, expressed concern about ‘destitute’ non-volunteers who were being paid some money to help around the camp. He wrote that, for the most time, ‘they are condemned to inactivity…In this state they become lazy or crazy, or both.’Footnote 71 He reported this to the Home Office in the hope that there would be ‘funds available for helping such cases’. Soon after, the Home Office started providing them with ‘pocket money’.Footnote 72 Such attitudes by camp staff appear to have been appreciated by some of the prisoners: according to one anecdote, upon release, a Frenchman handed the guard some money and asked for it to be given to the Red Cross ‘as a token of appreciation for the kindness extended to him’ while in RPS.Footnote 73

Yet here again attitudes were not universal. When in 1942 the DMI and the Directorate of Naval Intelligence suggested that a more ‘cheerful’ atmosphere be adopted in the camp, given that to them detainees were valuable assets, MI5's director general emphasized that the use of RPS for intelligence-gathering was ‘in the nature of a gift’ and that the primary reason the camp existed was to ensure ‘that no enemy agents or dangerous suspects shall enter the country undetected’. More tellingly, he asserted that these were ‘refugees from an intolerable state of affairs in their own country – violence, concentration camps, starvation’, whereas in RPS they were ‘safe, reasonably well-housed and fed’.Footnote 74 In other words, by offering conditions that were better than what they had left behind, RPS was good enough since, in MI5's eyes, refugees were suspects until proven otherwise.

III

While there were incentives to maintain RPS until the end of the war, there were also incentives not to alienate Britain's Allies – whose nationals made up the majority of detainees – in the process. These aims were reconciled through diplomacy, regulation, and propaganda, and through the efforts of the Home and Foreign Offices, whose involvement ensured that life in RPS contrasted sharply to that in camps across Europe, most obviously in occupied territory. It is due to them that RPS, despite being a detention camp, looked like a reception centre.

Administratively, RPS was always under the Aliens Department of the Home Office: on paper, it was the latter's immigration officers who could order a person's dispatch from the port to RPS, and it was again immigration officers who could order one's release from the camp. In reality, however, they were following the direction of MI5 in every step of the process. For the avoidance of doubt, explicit instructions to that effect were issued in March 1941.Footnote 75 The War Office was also involved by providing administrative staff and guards, and also appointed RPS's first commandant (the one who asked for funds for ‘destitute’ cases).Footnote 76 The Home Office's involvement in RPS was nevertheless not altogether nominal: they intervened on a number of occasions to ensure that living conditions were satisfactory. One of their first interventions occurred as early as January 1941, when they realized that MI5 was keeping very few records, causing people to be forgotten in the camp for days.Footnote 77 To avoid such cases becoming the norm, the Home Office suggested that a daily list of arrivals was kept so that the duration of detention could be monitored. Soon after, all documents produced during a person's stay were kept on file, and similarly thorough records were kept for personal property, to avoid any complaints of theft inadvertently attracting attention.

Another significant intervention came in the form of a sub-committee of the Home Defence (Security) Executive, the latter having been established in May 1940 to deal with ‘the dangers of the “Fifth Column”’.Footnote 78 Its RPS sub-committee was set up soon after RPS opened in 1941 and after Lord Swinton, chair of the Executive, expressed concern over the planned detention of Norwegians brought back from the Lofoten raid.Footnote 79 After all, those men had fought alongside the British and yet they were about to be put behind barbed wire. It was then that the suggestion was made to transform RPS into ‘a really presentable Volunteer Transit Centre’, helping to ‘disguise as much as possible [RPS's] nature as a place of detention’, rather than restrict its remit.Footnote 80 What was also decided at that point was RPS's formal name – it became the ‘London Reception Centre’.Footnote 81

In pursuit of this change in atmosphere, the sub-committee was assisted by several parts of British culture. The British Council supplied the camp with works by Brontë, Kingsley, Dickens, Austen, Kipling, and Yeats, despite most arrivals not being able to read English; a smaller selection of foreign literature was later made available.Footnote 82 The British Film Institute loaned RPS a projector, so that detainees would watch Popeye, Jessie Matthews movies, and Ministry of Information propaganda.Footnote 83 Portraits of the royal family and Churchill were put up on the walls,Footnote 84 playing cards and dartboards were made available, and table tennis sets and footballs were purchased from Selfridges.Footnote 85 A piano was also bought from Harrods in 1942, with the first recital given by a British captain and a female Russian pianist.Footnote 86 (On most other nights, it was the refugees who played their national anthems on a second, out-of-tune piano, much to the annoyance of staff whose room was next door.Footnote 87) To oversee day-to-day life in the camp, a welfare officer was also employed, tasked with making a refugee's ‘sojourn as pleasant as possible, both physically and mentally’.Footnote 88 The resulting activities included dancing and croquet, ‘cinema shows, concerts, billiards…and of course, various literary activities’.Footnote 89 What proved more difficult was removing the barbed wire from around the camp, as the War Office was unwilling to double RPS's guard to thirty to fill the gap that this would create. But the benefit of not attracting attention – ‘if one wishes to avoid the impression that the Patriotic School is a detention camp, then it is essential that the outward and visible signs of restriction should be as unobtrusive as possible’Footnote 90 – outweighed the risk of escapes, and so it was removed regardless. Much less determination for improvement concerned the building of an air raid shelter, which never materialized. Despite the issue having been discussed by the sub-committee, and despite RPS having been set up during the Blitz, building a shelter proved impractical.

Aside from redecoration, diplomacy with Britain's Allies was crucial in keeping RPS intact, as well as in keeping with the overall good inter-Allied relations that were maintained in the country, despite occasional conflicts.Footnote 91 Not everyone co-operated immediately; in the early months, the Free French made a number of demands, such as that officers be segregated from civilians, that the French be segregated from other nationalities, and that white Frenchmen be segregated from black Frenchmen.Footnote 92 While it does not appear that those requests were met, it was agreed that a welcome letter from General de Gaulle would be distributed to French arrivals,Footnote 93 while British representatives of the Free French were among the first to visit the camp in 1941.Footnote 94 Even so, in his memoirs de Gaulle insisted that RPS was there to recruit Frenchmen for ‘the British Secret Services’.Footnote 95 It is unclear how accurate this accusation was because although MI6 were recruiting in RPS, they had been asked by MI5 not to tempt those who wanted to join the Free French.Footnote 96

On the whole, however, and especially after the sub-committee instructed the Foreign Office to write to the various Missions in 1941, calling for their co-operation over RPS, few problems arose. Ministers of the Norwegian, Dutch, and Yugoslav governments-in-exile were invited to visit RPS and expressed satisfaction with the premises;Footnote 97 whenever large parties arrived at once, a representative of their government was also allowed to welcome them in person, a gesture that both ‘appeased’ the Allies and gave legitimacy to the process – after the Dutch sent a welfare officer to welcome one such party, MI5 told the Home Office that ‘frankly, we would have welcomed the attendance of a more distinguished representative who could have…made our task easier by explaining the necessity for a detention’.Footnote 98 Although there were some complaints along the way – both from detainees and their representatives – most concerned the duration of stays rather than any other aspect of the process; some of the complaints also stemmed from an Allied desire to be more involved in RPS from an intelligence perspective (a desire MI5 objected to).Footnote 99

As important as inter-Allied relations were in their own right, there were more reasons why RPS could not look like a detention camp. One problem that the Foreign and Home Offices were trying to avoid was substantiating German propaganda. Anything less than good treatment would have given credence to enemy claims, namely that prospective volunteers ‘are put in Concentration Camps’, discouraging future recruits; arrangements had to thus ‘allow of generous and friendly treatment that would not be accorded to suspects’.Footnote 100 Accordingly, those arriving as volunteers were being transported to RPS in buses and cabs rather than police vans, while the officers escorting them had to be in plain clothes and introduce themselves as ‘guides’.Footnote 101 The Home Office also emphasized the good attitude that ought to be adopted when it came to French volunteers in particular, as they ‘have taken an extremely difficult decision in coming to this country and have done so at great personal risk – a risk greater in their case than in that of other Allied nationals, who come to this country with the approval and support of their recognised Governments’.Footnote 102 It would, in fact, not be unreasonable to suggest that some of these arrivals never knew of their status, and indeed two former detainees who discussed RPS after the war appear to have described it not as a detention camp, but as a vetting centre for Allied recruits.Footnote 103

Domestic awareness of RPS was also a concern. Parliament was frequently asking questions about the funds made available for various security operations, and questions about the camp would have been likely, had its true purpose been revealed. This meant that although the commandant was answerable to the Home Office, he was initially put onto MI5's payroll, explicitly to avoid parliamentary scrutiny of his salary and hence of his role; the same arrangement existed for the welfare officer.Footnote 104 Public opinion was similarly a concern.Footnote 105 British attitudes were at a turning point by the time RPS was set up in the winter of 1940/1, because incidents like the sinking of the SS Arandora Star, carrying ‘enemy’ civilians being deported to Canada, had created uneasiness regarding mass internment. As a result, the internment of ‘enemy aliens’ that was supported in early 1940 was regretted soon after and partially reversed. If RPS policy was not to be reversed in a similar way, public opinion had to remain dormant.

It is for all these reasons that RPS could not look like a place of detention. Still, despite the various improvements, the camp was not perfect – the welfare officer himself suffered a nervous breakdown due to the workload. Fights also broke out occasionally, and so the Home Office wanted to make a room available for ‘boxing and wrestling’, to prevent detainees from partaking in such action ‘whenever convenient in the Dining Hall’.Footnote 106 The commandant also complained to the Home Office in the autumn of 1942 that the duration of detention was having an impact on morale: ‘guests arrive in this country full of zeal for the British, but after a time resentment sets in and increases in proportion to the length of stay’; even worse, he wrote that some had ‘developed suicidal tendencies owing to the length of their stay’.Footnote 107 What exacerbated the situation was that, in many cases, stays in RPS were on top of stays in ‘overflow’ centres. When RPS was requisitioned, at a time when refugee policy was being restricted, its capacity for 350 people made it ‘a little too large for the purpose’.Footnote 108 However, the growing use of RPS by intelligence meant that it was often overcrowded. To accommodate those awaiting interrogation when RPS was full, the Camberwell Institute, with capacity for 600 people, was requisitioned in 1941. Such were the numbers involved that other premises were needed for when even the overflow centre was overflowing. But welfare arrangements in Camberwell – which started being used almost continuously in the winter of 1942 – were inexistent.Footnote 109 There were no pianos and no croquet, and so people spent their days in bed; due to air strikes, the windows were bricked up, making the place dark and poorly ventilated; the cleaners also threatened to go on strike over the ‘misuse’ of the lavatories.Footnote 110 The conditions were demoralizing, especially for prospective volunteers; it took this realization on the impact of Camberwell on morale, a complaint by the Belgian ambassador to the same effect, and an intervention by Herbert Morrison, the home secretary, to bring about the use of a more suitable overflow building in mid-1943.Footnote 111 Amidst those developments, and again at Morrison's orders, the Home Office transferred the commandant and the welfare officer onto its payroll, clarifying in this way the line of responsibility between it and MI5, halfway through operations.Footnote 112 Subsequent overflow centres were considered satisfactory and few problems arose concerning the process until it ceased completely in the summer of 1945: port officers began sending new arrivals back to their own countries after May, overflow centres were gradually restored to their original functions (usually schools), and RPS was returned to the Ministry of Works.

IV

With the exception of overflow centres in 1942/3, the aim of providing a comfortable experience for non-enemy civilians was achieved, most of the time. Why these people were detained in the first place was the first question this article set out to answer. The existence of RPS was a product of the 1940 ‘spy fever’; but the picture within it became more complex. Primarily seen as suspects by MI5, as intelligence sources by the War Office and the users of its reports, as well as nationals of Britain's Allies by the Home and Foreign Offices, RPS was a microcosm of a complicated and sometimes contradictory relationship between non-Britons and the state, with the former simultaneously seen as a threat, as an asset, and as allies.

Who these people were was the second question posed. Those RPS held came from a range of backgrounds – there had been weeks when twenty-eight nationalities were there at once, each with different languages, habits, diets, and class backgrounds.Footnote 113 Nonetheless, this diverse population had one thing in common: they were not working for the enemy. Many of RPS's ‘guests’ and ‘informants’ were Allied men eligible for enlistment, many of whom had travelled to Britain precisely with that aim; a smaller proportion were women and children again of Allied nationality, as well as men from neutral countries. The interrogation reports detailing their stories are invaluable, not just for the purpose of tracing RPS's history but because they appear to be the most detailed source that exists on this population: these people were not seen as immigrants by the authorities, and hence there was no effort to register their arrival, let alone to record any more detail about what they had experienced. In contrast, the reports that the Directorate of Military Intelligence produced, although concerning only a proportion of the detainees, offer both demographic information and, in many cases, detail individuals’ wartime experiences.

What allowed RPS to operate unobstructed until the end of the war – the final question posed – was the development of a bureaucracy between its stakeholders, which enabled Britain to take advantage of this source of information without being criticized for doing so through detaining them, often for weeks. The Home Office improved the administration of the camp, keeping Allied complaints to a minimum; it often did so with the assistance of the Foreign Office. For its part, MI5 understood diplomatic concerns and accommodated them, often by footing the bill and often with the assistance of the War Office which provided guards and administrative staff. The fact that this multi-purpose camp was in London must also be emphasized, especially given that an air raid shelter appears not to have been constructed. The legacy of RPS as a detention, intelligence, and refugee camp would have been very different had hundreds of Allied civilians been killed while being detained for information – dozens of bombs landed in Wandsworth Common during the Blitz and more exploded near where Nightingale Lane was; both areas were targeted again in 1944. In the fortunate absence of such developments, a combination of regulation, diplomacy, and propaganda turned RPS into a forgettable ‘London Reception Centre’, and a forgotten site of multinational wartime Britain.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Professor Heather Jones and Dr Dina Gusejnova for valuable feedback on earlier drafts.

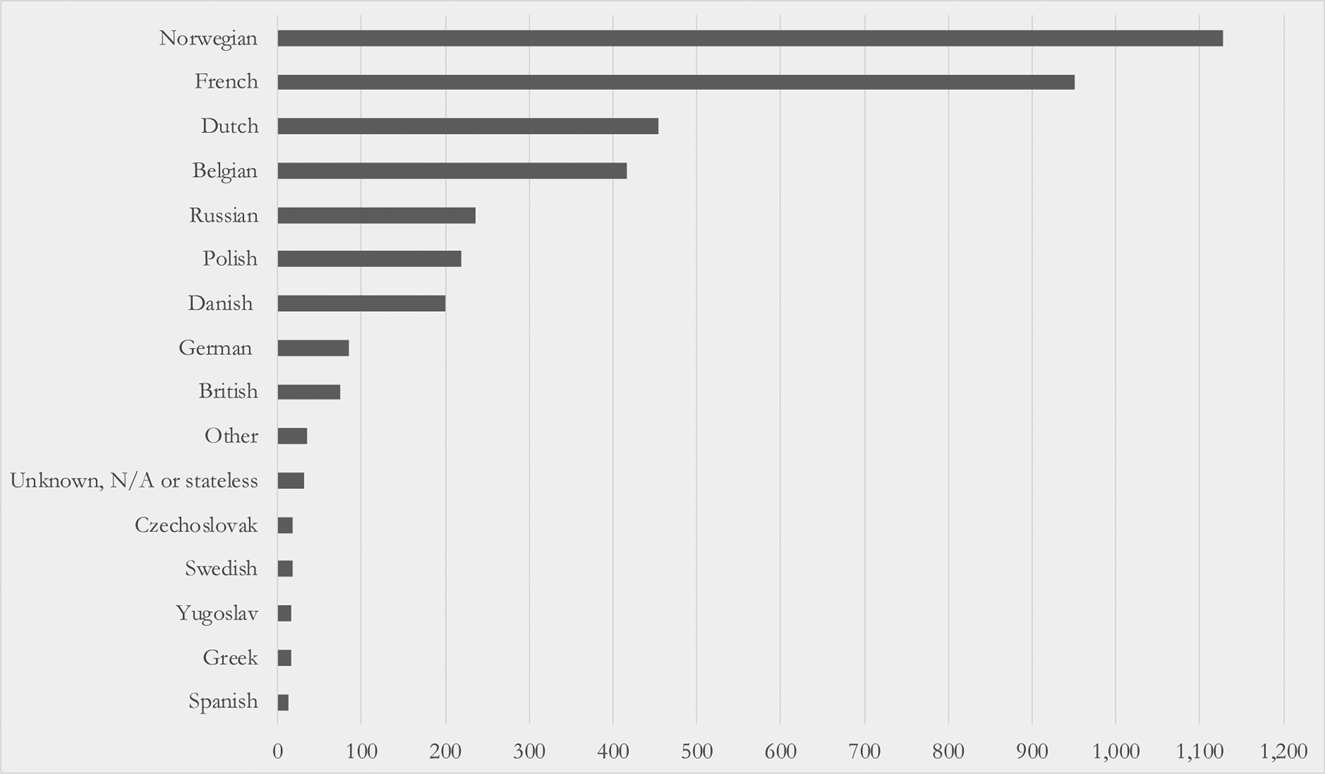

Appendix 1: Monthly RPS arrivals, January 1941–May 1945