Article contents

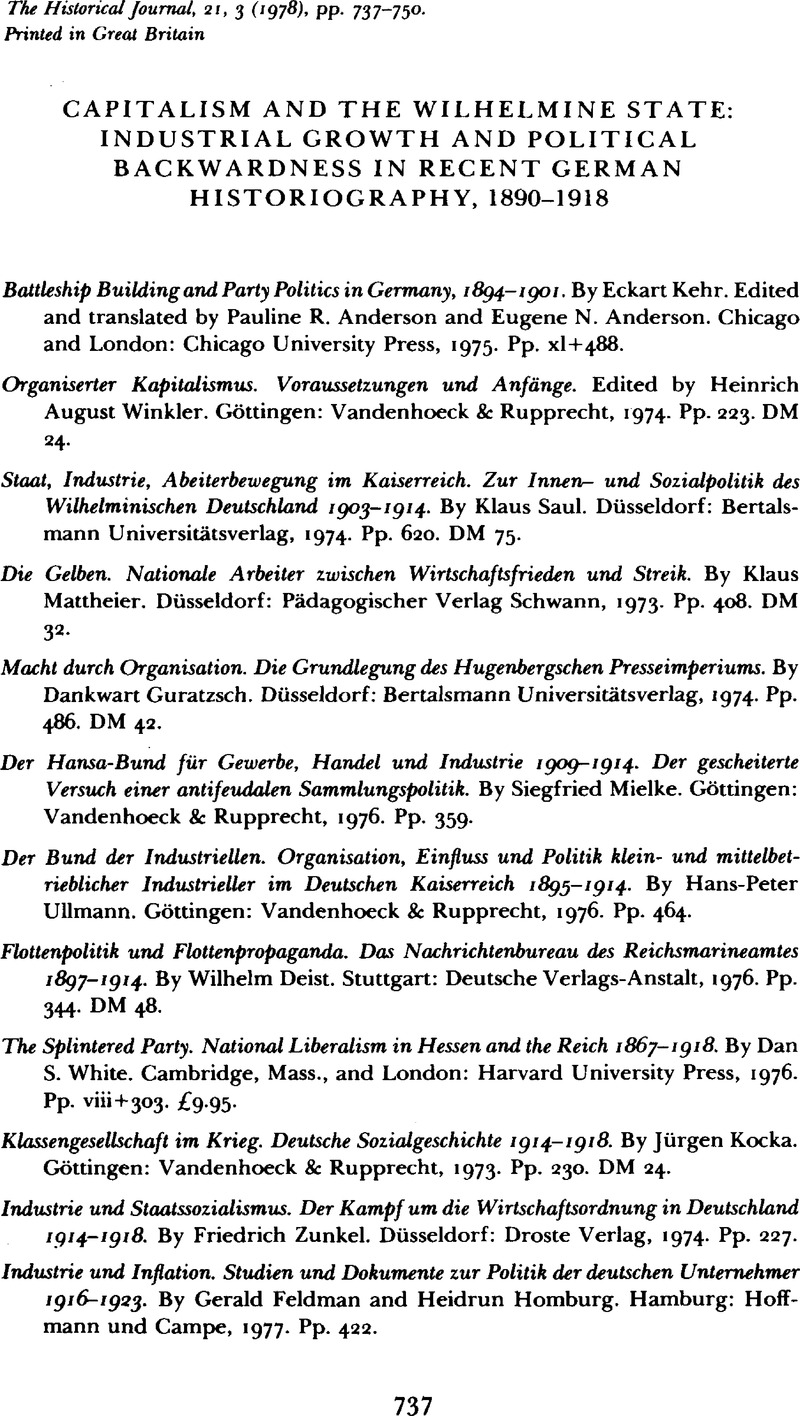

Capitalism and the Wilhelmine State: Industrial Growth and Political Backwardness in Recent German Historiography, 1890–1918

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1978

References

1 The scope of the discussion has been strictly limited to this single theme, and the books under review have been considered with this specific purpose in mind. In some cases this clearly under-values the book concerned, for the latter's problematic need not coincide exactly with the one defined here. I am thus very conscious of being unable to do some of the authors full justice. This is notably true of Kocka's fine study of the First World War and its impact on German society, which is one of the best achievements of the new history in the Federal Republic, and of the individual essays edited by Fritz Klein, which are likewise amongst the best recent work from the G.D.R. The works of Deist and White also make major contributions which fall outside the review's terms of reference, whilst those by Feldman and Homburg and Gessner deal mainly with the period after 1918. Similary, there are many areas of controversy (e.g. the debate over naval policy and social imperialism) which arise from the reception of Kehr's ideas which cannot be gone into here.

2 The essays edited by Winkler originated in a symposium at the Regensburg Historical Congress in 1972. Whilst Kocka handled the task of general definition of ‘organized capitalism’, others provided a series of national case-studies: Hans-Ulrich Wehler on Germany, Hans Medick on Britain, Volker Seilin on Italy and so on, with Gerald Feldman and Charles Maier exploring later German developments in the years after 1914. For a particularly useful response to the symposium, see: Geyer, M. and Lüdtke, A., ‘Krisen-management, Herrschaft und Protest im organisierten Monopol-Kapitalismus (1890–1939)’, Sozialwissenschaftliche Informationen für Unterricht und Studium, IV (1975), 12–23.Google Scholar I have also benefited from a reading of an unpublished paper by C. Medalen, ‘The Hibernia Affair’.

3 There is no space to explore these ideological implications, but Hilferding's theory as expounded by Winkler clearly anticipates more recent social democratic thinking. Winkler himself appears to be arguing the historical legitimacy of the SPD's practice in the 1920s, and explicitly upholds ‘liberal democracy as a political principle’ in his exposition (p. 15).

4 Wehler, H.-U., Das deutsche Kaiserreich 1871–1918 (Göttingen, 1973), pp. 138ff., 238.Google Scholar

5 Stegmann, D., ‘Hugenberg contra Stresemann. Die Politik der Industrieverbände am Ende des Kaiserreichs’, Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, XXIV (1976), 337.Google Scholar

6 In making this point I have benefited from a reading of Pogge von Strandmann, H., ‘Widersprüche im Modernisierungs-prozess Deutschlands. Der Kampf der verarbeitenden Industrie gegen die Vormacht der Schwerindustrie’Google Scholar, to be published in the second Festschrift for Fritz Fischer, 1978. There is also an excellent conspectus of these developments in Willibald Gutsche's essay in the Klein volume, pp. 33–84: ‘Probleme des Verhältnisses zwischen Monopolkapital und Staat in Deutschland vom Ende des 19 Jahrhunderts bis zum Vorabend des ersten Weltkrieges’.

7 See Wehler in his contribution to Winkler, , p. 52Google Scholar; also Kocka, , pp. 120ff.Google Scholar

8 Though his own understanding of politics was more subtle than this, Kehr's study of naval policy has given this approach much impetus. For three major examples, see: Böhme, H., Deutschlands Weg zur Grossmacht (Cologne, 1966)Google Scholar; Stegmann, D., Die Erben Bismarcks. Parteien und Verbände in der Spätphase des Wilhelminischen Deutschlands. Sammlungspolitik 1897–1918 (Cologne, 1970)Google Scholar; Berghahn, V. R., Der Tirpitz-Plan(Düsseldorf, 1971).Google Scholar Moreover, it has been generalized into a series of influential essays: Nipperdey, T., ‘Interessenverbände und Parteien in Deutschland vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg’, Wehler, H.-U. (ed.), Moderne Deutsche Sozialgeschichte (Cologne, 1966), pp. 369–88Google Scholar; Schulz, G., ‘Uber Entstehung und Formen von Interessengruppen in Deutschland seit Beginn der Industrialisierung’, Varain, H. J. (ed.), Interessenverbände in Deutschland (Cologne, 1973), pp. 25–54Google Scholar; Fischer, W., ‘Staatsverwaltung und Interessenverbände in Deutschen Reich 1871–1914’, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft im Zeitalter der Industrialisierung (Götungen, 1972), pp. 194–213CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Puhle, H.-J., ‘Parlament, Parteien und Interessenverbände 1890–1914’, Stürmer, M. (ed.), Das kaiserliche Deutschland (Düsseldorf, 1970), pp. 340–77.Google Scholar

9 See Althusser, L., ‘Ideology and ideological state apparatuses (Notes towards an investigation)’, Lenin and Philosophy and other Essays (London, 1971), pp. 121–76.Google Scholar

10 This is a general failing of the books under review, but is perhaps especially marked in the case of Guratzsch and Saul, whose discussions of respectively the press and the law totally lack such a theoretical dimension.

11 Apart from Maier's contribution to the Winkler essays, see his Recasting bourgeois Europe (Princeton, 1975).Google Scholar

12 Wehler, , Das deutsche Kaiserreich, p. 63.Google Scholar

13 In fact, it could be argued that Kocka's analysis of the state in his monograph on the First World War (which he presents as a critique of a ‘Marxist’ view) comes closer to a Marxist approach than his avowedly ‘Marxist’ general model of ‘class society’, which bears little correspondence to recent Marxist discussions of class. In general see the works of Poulantzas, N.: Political power and social classes (London, 1973)Google Scholar; Classes in contemporary capitalism (London, 1975)Google Scholar; ‘The capitalist state: A reply to Miliband and Laclau’, New Left Review, XCV (01–02 1976), 63–83.Google Scholar

14 Poulantzas, , Political power and social classes, p. 190.Google Scholar

15 Poulantzas, , ‘The capitalist state’, p. 75.Google Scholar

16 Poulantzas' characterizations of these two positions provides an accurate commentary on the false polarity which ‘Kehrite’ thinking has tended to produce: ‘Either the dominant classes absorb the State by emptying it of its own specific power (the State as Thing in the thesis of the merger of the State and monopolies upheld in the orthodox communist conception of “State monopoly capitalism”); or else the State “resists”, and deprives the dominant class of power to its own advantage (the State as Subject and “referee” between the contending classes, a conception dear to social democracy)’. See ibid. p. 74.

17 A number of serious technical criticisms can be levelled at these books as a whole. Thus as well as the absence of adequate conclusions, few of them possess a servicable subject index on the English model. On the other hand, Saul, Guratzsch, Mielke, Ullmann, and to a lesser extent Zunkel and Kocka all suffer from a ridiculous surfeit of source-references. In Saul the references comprise some 200 pages as against 400 of text, in Mielke some 150 against 180, and in Ullmann some 200 against 230. On a typical page of Ullmann (p. 146) there are a total of twenty-one references filling one and a half pages of small print at the back of the book. This makes the books impossible to read with any sense of continuity, let alone enjoyment. More seriously, it can signify a rather narrow positivist understanding of historical explanation. Yet curiously, in the Feldman–Homburg edition of documents, where an elaborate footnote apparatus becomes essential in order to make sense of the organizations, events and personalities, the references are kept down to a minimum. As an edition this compares rather badly with, say, the splendid Quellen zur Geschichte des Parlamentarismus und der politischen Parteien, published by the Kommission of the same name, which have set exacting standards for this kind of venture.

18 See Kocka, , pp. 65–95Google Scholar, for a general discussion; Ullmann, (pp. 138–60)Google Scholar and Mielke, (pp. 95–101)Google Scholar for attempts by the BdI and Hansabund to woo white-collar workers; and Guratzsch, (pp. 26–62, 88–95, 117–26, 363–78) for land reform and cooperative movements in the East.Google Scholar

19 See especially Stegmann, , Die Erben Bismarcks, pp. 26–8, 146–65, 219–31, 305–15.Google Scholar

20 White's study is the most valuable work dealing with the National Liberals to be published in recent years, and deserves far more attention than I am able to give it in this context. It grasps more firmly and imaginatively than virtually any other recent work that the National Liberals were also an agrarian party at the turn of the century, and that the crisis of that party was in large part the crisis of its defecting rural constituency.

- 9

- Cited by