No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

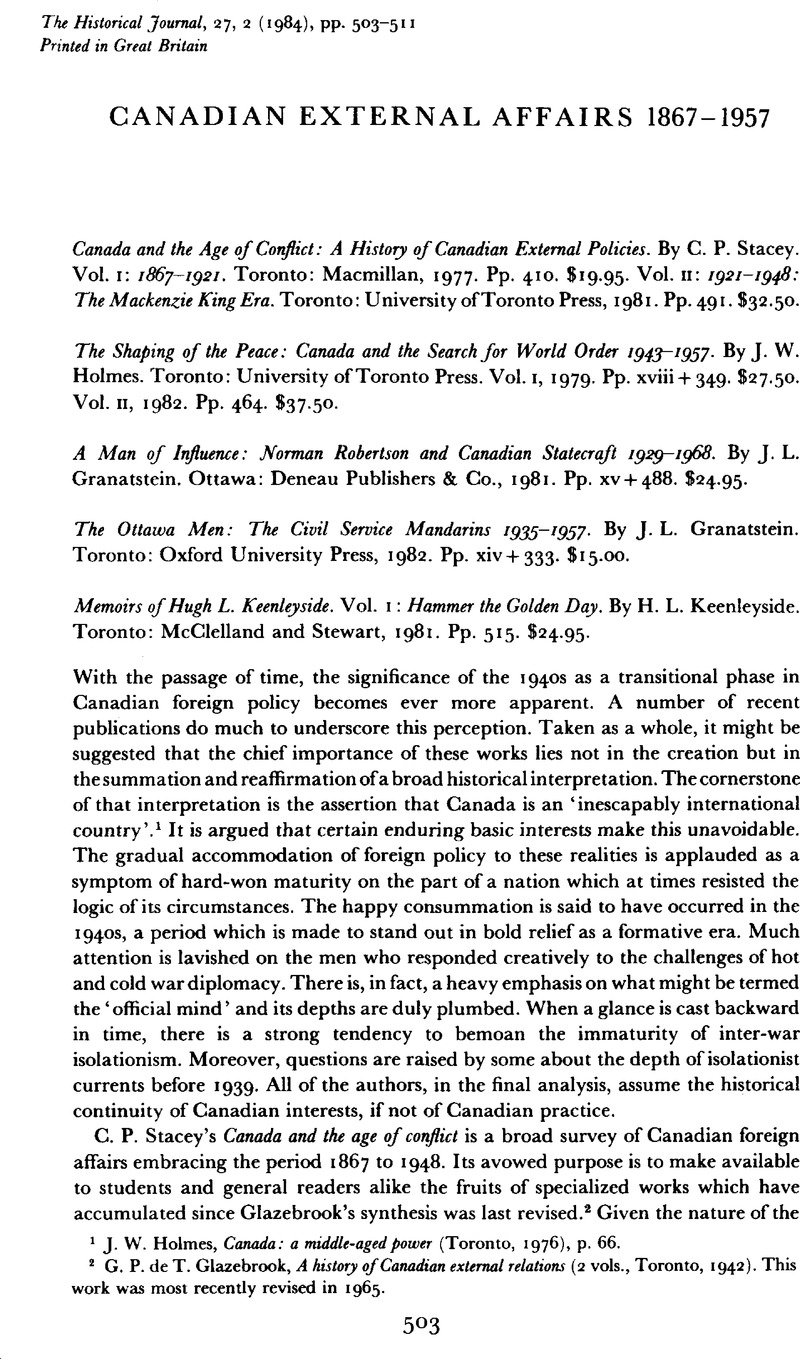

Canadian External Affairs 1867–1957

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1984

References

1 Holmes, J. W., Canada: a middle-aged power (Toronto, 1976), p. 66CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

2 Glazebrook, G. P. de T., A history of Canadian external relations (2 vols., Toronto, 1942)Google Scholar. This work was most recently revised in 1965.

3 Among Stacey's, major works one should note Canada and the British army (Toronto, 1936)Google Scholar; The Canadian army, 1939–1945: an official history summary (Toronto, 1948); A very double life: the private world of Mackenzie King (Toronto, 1976); Mackenzie King and the Atlantic triangle (Toronto, 1977)

4 Brown, R. C., Robert Laird Borden: a biography (2 vols., Toronto, 1975, 1980)Google Scholar. Stacey borrows from a series of articles by Brown which are subsumed in the biography.

5 For Creighton's last major statement of the theme see Creighton, D. G., The forked road: Canada 1939–1957 (Toronto, 1976)Google Scholar.

6 Hillmer, N., ‘The Anglo-Canadian neurosis: the case of O. D. Skelton’ in Lyon, P. (ed.), Britain and Canada: survey of a changing relationship (London, 1976), pp. 61–84Google Scholar.

7 Berger, C., The sense of power: studies in the ideas of Canadian imperialism 1867–1914 (Toronto, 1970)Google Scholar.

8 Ironically, at times it was the British who were urging Ottawa to assume more responsibility for its own consular matters. An interesting example of this occurred in Cuba, where between the wars the British embassy came to handle more Canadian than British business, and begged for relief. On this point see Ogelsby, J. C. M., Gringos from the far north: essays in the history of Canadian-Latin-American relations 1866–1968 (Toronto, 1976), p. 288Google Scholar.

9 For a discussion of the views of those such as Creighton and Eugene Forsey who have levelled these charges see Berger, C., The writing of Canadian history (Toronto, 1976), pp. 228–33Google Scholar.

10 Grant, G., Lament for a nation (Toronto, 1965)Google Scholar.

11 Ferns, H. S., ‘Bureaucrats in battle’, Times literary Supplement (27 11. 1981), p. 1396Google Scholar.

12 Other memoirs from the period include Pearson, L. B., Mike: the memoirs of the Rt. Hon. Lester B. Pearson (Toronto, 1972)Google Scholar. Charles Ritchie's third volume of his chatty diary excerpts has recently appeared; see Ritchie, C., Diplomatic passport (Toronto, 1981)Google Scholar. See also Wilgress, D., Memoirs (Toronto, 1967)Google Scholar.

13 For examples of Keenleyside's scholarship see Keenleyside, H. L., Canada and the United States (Toronto, 1929)Google Scholar and Keenleyside, H. L. et al. , The growth of Canadian policies in external affairs (Durham, N.C., 1960)Google Scholar.

14 For a discussion of Canada's policy at Geneva see Veatch, R., Canada and the League of Nations (Toronto, 1975)Google Scholar.

15 Tucker, M., Canadian foreign policy: contemporary issues and themes (Toronto, 1980), p. 1Google Scholar.

16 Pearson's comment is cited in Tucker, ibid. p. 5.

17 Apart from some of the authors reviewed here, others have also argued that the force of isolationism has perhaps been exaggerated. Berger, Carl, in his The writing of Canadian history (Toronto, 1976), p. 147Google Scholar, draws attention to ‘the vogue of internationalism’ in the historical literature of the twenties. Hillmer has argued that Skelton viewed isolationism merely as a temporary policy. See Hillmer, ‘Skelton’, p. 80. Harvey Levenstein has demonstrated that considerable jingoistic fervour could occasionally be aroused even in the thirties. See Levenstein, H., ‘Canada and the suppression of the Salvadorean revolution of 1932’, Canadian Historical Review, LXII (1981), 451–69CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

18 Glazebrook, External relations, 11, 40.