Around the middle of the eighteenth century in France, something spectacular happened in women’s fashion. Flowers began to sprout from hairstyles, from bosoms, from stomachers, and from skirts. At first, these floral accessories were tiny, delicate blossoms that were barely noticeable in a portrait or fashion plate (Figure 1). However, as the century wore on, flowers came to define the aesthetic of many fashionable young women (Figure 2). In 1818, the writer and courtier Stéphanie-Félicité Comtesse de Genlis (1746–1830) reflected nostalgically on the sumptuous fashion on display at the court of Louis XVI. ‘It is impossible to give a sense of the brilliance of a circle composed of thirty well-dressed women,’ she wrote. ‘Their enormous panniers created a rich trellis, artistically covered with flowers’ (Figure 3).Footnote 1

Figure 1. While three-dimensional flowers featured in fashion before the mid-eighteenth century, they were often small and somewhat generic, such as the flowers depicted here in the hair of the marquise d’Argence. Jean-Marc Nattier, Marie Françoise de la Cropte de St Abre, marquise d’Argence, oil on canvas, 1744, 82.6 × 64.8 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 58.102.1. Open access, public domain.

Figure 2. Fashion from the 1760s onwards incorporated exuberant floral displays of realistic-looking blooms. François Boucher, Madame Bergeret, oil on canvas, possibly 1766, 143.5 × 105.4 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 1946.73. Open access, public domain.

Figure 3. This fashion plate from the Gallerie des modes gives a sense of a ‘rich trellis’ of panniers covered in flowers, as described by the comtesse de Genlis. Nicolas Dupin, after a drawing by Augustin de Saint-Aubin, in Madame Le Beau, 2e cahier de grandes robes d’etiquette de la cour de France faisaint suite aux costumes français, Gallerie des modes et costumes français (Paris, c. 1787). Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, RP-P-2009-1216. Open access, public domain.

Demand for floral fashion increased in tandem with the skills of artificial flower-makers during the eighteenth century. Although real flowers, interspersed with occasional artificial blooms, had been worn for religious and secular festivals for centuries in Europe, the application of new discoveries in chemistry and in botany to artificial flower-making in eighteenth-century France greatly expanded the creative possibilities for incorporating flowers into fashion.Footnote 2 This article interprets the motivations for consumption and production of artificial flower accessories at the height of their popularity, through the records of France’s most successful fashion merchant, Marie-Jeanne (Rose) Bertin (1747–1813) – whose career developed from relative obscurity to becoming Marie-Antoinette’s favourite marchande de modes. I demonstrate how French artisans and merchants came to dominate the European fashion market in the late eighteenth century, with Bertin exporting artificial flowers to customers in England, Spain, Sweden, and Russia.

Delving deeper into the types of flowers that were sold reveals the extent of women’s engagement with botany through clothing. Artificial flower-makers possessed the skills to differentiate between different varieties of the same species of flower, and the knowledge to create at least seventy-five different types of flowers. The narrative that emerges indicates that communities of (predominantly female) makers and consumers made conscious, informed, and meaningful decisions about which flowers to incorporate into their clothing.

The article begins with an overview of the relevant historiography, a summary of artificial flowers in the history of fashion, and a discussion of the unique source base at the heart of this study. The second section explores the chronology of flowers in Bertin’s credit records, analysing events and trends that caused the sales of flowers to rise and fall. Section three focuses on the types of flowers that Bertin sold, exploring the significance of the most popular varieties, while the fourth section discusses the presence of rare, exotic, and unusual flowers. The picture presented here mediates between macro- and micro-level analyses of artificial flower consumption, arguing that events on both a national and an international level affected general trends in fashion, alongside personal circumstances for individual consumers which impacted their choices of flowers.

My approach in this article is informed by material culture studies, which argue that objects shape communities, identities, and human interactions with the world around them. Most recently, Burghartz et al.’s Materialized identities has demonstrated that materials such as glass, veils, and feathers possessed ‘agentive qualities of matter’ that stimulated affective responses in early modern consumers. The editors contend that, in the pursuit of new ‘ingenious materials and fashions’, artisans and consumers ‘cultivated new sensibilities for material qualities’ of these objects – such as softness, lustre, and transparency – which ‘in turn stimulated their buying behaviour’.Footnote 3 My study positions flowers as comparable objects that aligned with the sensibilities of eighteenth-century culture, and thus became a coveted consumer good in this period. I argue that the attractive qualities of vibrant colours, scent, and delicacy aligned with societal expectations of ‘natural’ femininity to create a vogue for floral fashion in this period.

In the past thirty years, studies have separately acknowledged both the role of gardening and the role of fashion in shaping elite identity in ancien régime France. However, there has been little exploration of the two in tandem. Chandra Mukerji’s publications of the 1990s argued that the ‘territorial ambitions’ of Louis XIV’s government were expressed in microcosm through the forests, canals, and topography of the gardens at Versailles.Footnote 4 Building on Mukerji’s work, Elizabeth Hyde argued in her 2005 text, Cultivated power, that growing ornamental flowers helped Louis XIV and the nobility to demonstrate their elevated taste for beauty and rarity.Footnote 5 Although Hyde ends her study at the beginning of Louis XV’s reign, arguing that the Sun King’s great-grandson was less interested in flowers as symbols through which to communicate royal power, works by Emma Spary and Sarah Easterby-Smith suggest that a fascination with ornamental plants persisted throughout the eighteenth century in the merchant classes and the bourgeoisie.Footnote 6 This interest was aesthetic, as different types of flowers came in and out of fashion; it was intellectual, as new systems of plant classification were proposed in scientific communities; and it was commercial, as increasingly globalized trade and exploration brought new species onto the French market. Furthermore, recent work by Susan Taylor-Leduc on the garden patronage of female consorts places women at the heart of horticultural developments at the French court from Marie-Antoinette onwards.Footnote 7 As this literature and the present article demonstrate, interest in flowers persisted among bourgeois and elite circles throughout the eighteenth century, and particularly among women.

Studies focusing on England have demonstrated how female artists drew on their skills in botany and fashion to create sophisticated designs displaying both knowledge and taste. Zara Anishanslin’s analysis of the Spitalfields silk designer Anna Maria Garthwaite (c. 1688–1763) and her upbringing reveals that she was enmeshed in networks of natural knowledge through her family connections. Garthwaite’s botanically detailed illustrations for dress silks both reflected and stimulated ‘the craze for wearing botanical landscapes’ at home and abroad.Footnote 8 Around the same time, Mary Pendarves, later Delany (1700–88), was designing intensely realistic floral embroideries for her court dresses, prefiguring the famous botanical collages she made later in her life.Footnote 9 Both these examples demonstrate that a love of fashion was not incompatible with scientific knowledge, and indeed the two could be combined successfully. In France, the application of botanical knowledge to creative design is perhaps best known in the case of Sèvres, where women played an important role in manufacturing porcelain flowers with high levels of detail and accuracy.Footnote 10 However, the emerging specialism of French artisans in creating artificial flowers in the eighteenth century – perhaps the most obvious connection between botany and fashion in this period – has drawn little notice from scholars, despite several studies acknowledging the size of the artificial flower industry in the early nineteenth century.Footnote 11

I

In Europe, artificial flowers first emerged in the context of religious festivals and rituals.Footnote 12 In 1599, Henri IV ratified the guild of feather-dressers and flower-sellers in Paris (plumassiers et bouquetiers) to make flowers mainly ‘for churches, as well as other bouquets for hats and bonnets’.Footnote 13 In 1784, the guild of flower-makers was incorporated with that of fashion merchants owing to the ‘dependence of their [fashion merchants’] profession’ on artificial flowers – demonstrating the shifting emphasis from religious usage to secular.Footnote 14

Despite the long existence of the artificial flower-makers within the guild system, Louis de Jaucourt’s entry for Diderot’s Encyclopédie in 1757 described flower-making as ‘a new art in France’. While Jaucourt acknowledged the long-standing tradition of nuns making flowers in convents, he was scathing about the quality of their work, especially compared to better-established workshops in China and in Italy. He declared that French artisans had only become proficient at making flowers since Monsieur Seguin from Gevaudan made an exacting study of chemistry and botany in 1738 to create flowers as naturalistic as those fashioned in Italy.Footnote 15 In Jaucourt’s narrative, the art of flower-making was elevated and legitimized through the application of scientific methods by men, which surpassed the unskilled efforts of religious women. This reading fits the wider schema of the Encyclopédie, in which scientific knowledge replaced religious practice, allowing French artisans to attain pre-eminence.Footnote 16 However, as this article argues, evidence from Bertin’s credit records supports the view that artificial flower-making was closely entangled with scientific (particularly botanical) knowledge. Furthermore, the fact that Bertin exported flowers from her shop across Europe suggests that French craft skills were particularly prized.

A more detailed entry in Roland de la Platière’s Encyclopédie méthodique from 1785, written with the assistance of the Parisian flower-maker Madame Wagon, gives a sense of the complex skills and tools required to fashion artificial flowers in late eighteenth-century France.Footnote 17 When viewed alongside the illustration produced for Diderot’s Encyclopédie (Figure 4), it is clear that a variety of different specialized craftspeople were employed in a workshop: male artisans and boys worked on colouring, preparing, and cutting fabric, while it was mainly women who attended to the fine details of flowers. Flower-makers began by dyeing batiste fabric (finely woven linen or cotton cloth) for petals, and taffeta for leaves, using gum arabic and starch to create firm glossy foliage. They cut out the shapes using a variety of moulds hammered into the material. Hot irons embossed delicate veins into the leaves and helped shape the petals. These pieces were then mounted on stems of boar-bristle, or steel wire for the largest blooms, which were covered with coloured paper and cotton.Footnote 18 The techniques described in the Encyclopédie méthodique are similar to those used by craftspeople making artificial flowers for haute couture houses today, demonstrating the effectiveness of the methodology.Footnote 19

Figure 4. An engraved plate from Diderot’s Encyclopédie shows men, women, and children working in an artificial flower workshop. Men are employed in cutting and stamping shapes, as well as hanging fabric to dry, while mainly women and children are shown working directly with the flowers. ‘Fleuriste artificiel’, plate 1, in Recueil de planches sur les sciences, les arts libéraux, et les arts méchaniques (11 vols, Paris, 1762–72), iv, book 3. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, AE25.E531 1762 Q. Open access, public domain.

Once artificial flowers left the workshop, they were sold alongside other luxurious accessories in the shops of fashion merchants. This study uses as its primary source the largest collection of receipts from a fashion merchant’s shop to survive from eighteenth-century Paris, compiled by the heirs of Marie-Jeanne Bertin. Bertin was born in Abbeville, the daughter of a member of the local constabulary and a nurse, and the youngest of six children.Footnote 20 She grew up in a region famous for its textile production, yet she chose to move to Paris to become an apprentice fashion merchant. Her star rose quickly. The young fashion merchant was soon noticed by members of the court elite, and in 1775 she designed the new queen’s robes for the coronation ceremony.Footnote 21 At the height of her career, Bertin counted among her clientele several royal families of Europe, and nobility at Versailles, as well as actors, dancers, and merchants. Her success was short-lived, however, as many of her clients were guillotined or fled into exile during the French Revolution.

The effects of the revolution on Bertin’s highest-spending customers meant that numerous bills drawn up on credit were never paid in cash. This was not unusual in a fashion system where customers who bought on credit often delayed payment for several years.Footnote 22 After Bertin’s death in 1813, her descendants hired a team of lawyers to track down former customers and encourage them to pay off their accounts. The lawyers identified 1,170 customers with outstanding debts, ranging from as little as 2 livres to the nearly 80,000 livres owed by the courtier Louise, Vicomtesse de Polastron (1746–1818).Footnote 23 In the library of the Institut national d’histoire de l’art (INHA) in Paris, a collection of manuscripts contains the lawyers’ efforts to locate 240 clients. Each client has a dossier complete with correspondence attempting to find the individual or their descendants; 234 of these dossiers contain copies of receipts for purchases made at Bertin’s shop, Au Grand Mogol, between 1772 and 1801.

It is unclear whether the files preserved at the INHA represent only the unsuccessful attempts to recoup money, since the included correspondence reveals that the lawyers never succeeded in persuading families to pay up. Perhaps the remainder of the 1,170 customers originally identified by Bertin’s heirs either paid their debts or could not be found. While the receipts preserved in this dataset represent a limited selection of Bertin’s total customers, in the absence of a more complete record of her sales, they nevertheless offer a tantalizing glimpse into the goods sold by France’s most famous fashion merchant over the course of her career. One of the few historians to have studied these records in detail, Clare Haru Crowston, calls the credit files ‘a crucial source of information about the fashion merchant’s business’.Footnote 24 This article is the first in-depth study of the files since Crowston’s 2013 book, however, and the only scholarship to date on the presence of artificial flowers in the records.

The scale of Bertin’s business and reputation meant that she employed a variety of specialist artisans.Footnote 25 This likely enabled her to provide a large range of flowers to adorn garments and to cater for specific flower requests. While there appears to be a higher concentration of flowers in her receipts than in other fashion merchants’ accounts, meaning that we must be cautious when extrapolating from this dataset, it is also true that the expertise of Bertin’s artisans enabled consumers to explore the full breadth of floral adornments.Footnote 26 It seems that, given the opportunity, women chose a wide range of specific flowers and were willing to pay considerable sums for them.

The amount of information available in the INHA files lends itself to a digital humanities approach, combining quantitative and qualitative analysis. The quantitative study was carried out using Microsoft Excel and Power BI, which enabled patterns in the dataset to become clear. The information was also assessed qualitatively, focusing on individual consumers and flower types to trace narratives through the data.Footnote 27

The results of this study are shaped by the limitations of the primary source base. The credit records represent an incomplete picture of Bertin’s sales, since any goods that were paid for promptly are not included in the dataset. Furthermore, it is likely that customers with outstanding credit bills had paid off part of their account already. For example, the files contain orders from Marie-Antoinette dating only from 1791 and 1792, whereas records from the queen’s household indicate that she was a regular customer of Bertin’s from 1774 onwards.

With these caveats in mind, the case study presented here should be regarded as an indication, rather than a comprehensive representation, of a much larger and more complex picture of artificial flower consumption within eighteenth-century Europe. Forays into the account books of other French fashion merchants confirm that the consumption of a wide variety of artificial flowers extended far beyond Bertin’s clientele. However, her prominent status and the concentration of fashion trend-setters within the bills preserved at the INHA mean that useful conclusions can be drawn from the following study about how and why flowers were consumed at the centre of European fashion in the late eighteenth century.

II

The first key finding of this study is just how popular artificial flowers were among Bertin’s customers with unpaid credit bills. Out of 234 account holders, 135 (58 per cent) bought flowers at some point. The receipts of these 135 purchasers contain 1,195 instances of artificial flowers being sold, making it clear that flowers formed a vital component of Bertin’s business.

Most customers who bought flowers did so in small quantities, with 113 buying ten flowers or fewer. A handful of consumers bought significantly higher numbers of flowers: among them Louise, Vicomtesse de Polastron; the princess Galitzen from Russia (probably Natalya Galitzen (1741–1837)); the duc de Luxembourg (probably Anne Charles Sigismond de Montmorency-Luxembourg (1737–1803)); and the queen of Sweden (Sophia Magdalena (1746–1813)). Indeed, the top ten consumers of flowers made almost half (46 per cent) of all flower purchases recorded in the credit files. While accounts with exceptionally large numbers of artificial flowers tended to be much longer overall than most receipts in these files, it seems that certain consumers had a marked preference for flowers. The significant presence of Russian and Swedish consumers within the top purchasers emphasizes the reach of Bertin’s business outside France.

As Figure 5 shows, the number of consumers who purchased artificial flowers roughly followed the trajectory of Bertin’s career, even as the number of flowers they bought varied considerably over time. Michelle Sapori suggests that Au Grand Mogol may have opened its doors in October 1773, although orders in this dataset from November 1772 suggest that Bertin may have started trading under her own name even earlier.Footnote 28 Her fortunes increased after her association with the duchesse de Penthièvre in 1774, and subsequently her work for Marie-Antoinette from 1775 onwards. Her business grew in the late 1770s and early 1780s, reached a plateau, and then suffered a sharp decline after the revolution. With the absence or death of many of her former clients from the French court, Bertin cultivated the foreign market, selling her goods abroad in Russia, England, Germany, and Spain. This helped sustain the fortunes of Au Grand Mogol in 1791 and 1792, but there are very few purchases of flowers – or indeed any goods – beyond 1793 in the credit files.

Figure 5. Number of purchasers of flowers over time, and the number of flowers purchased, in Marie-Jeanne Bertin’s credit files, 1772–93.

The exceptionality of certain consumers’ flower purchases has inevitable consequences for the data presented in Figure 5. The princess Galitzin’s receipts, for example, only cover the year 1780, so analysis of flowers sold over time will inevitably spike at this point, due to the ninety-five flowers that Galitzin ordered across the year. Most of the other prominent flower purchasers have receipts spanning several years, meaning that their impact on the dataset is less noticeable from an overview.

On average, the number of purchasers of artificial flowers gradually increased throughout the 1770s until 1782. However, there is a dip in purchaser numbers in 1781, and a significant decrease in the number of flowers they purchased. This is probably due at least in part to the death of Marie-Antoinette’s mother in late November 1780, which plunged Versailles into the strictest form of mourning dress (grand deuil) for six months, during which time women were prevented from wearing their usual colourful and extravagant accessories, including artificial flowers.Footnote 29

The data shown here suggests that the number of artificial flowers purchased continued to decline from 1783 onwards. As Table 1 indicates, although the number of purchasers in the years 1783–9 is similar to the numbers for 1777, 1778, and 1779, there were fewer flower purchases on average per person. Bertin’s flower sales may well have been affected by wider changes in hair and fashion during this period. The towering pouf hairstyles and enormous panniers that predominated in the late 1770s provided the perfect canvas for artificial flowers (see Figure 3). A trend for plain-coloured silks in court dress allowed accessories such as flowers to shine, in comparison to the busier patterns of the early eighteenth century (although visual evidence suggests that artificial flowers were sometimes worn alongside floral-patterned fabrics in the mid-century).

Table 1 Sales of artificial flowers in Marie-Jeanne Bertin’s credit records, 1772–93

The decline in Bertin’s flower sales per person in the 1780s might in part be explained by the increased simplicity of fashion and the diminishing size of hairstyles. Marie-Antoinette’s personal life had a significant impact on this fashion trend. In 1781, during her pregnancy with her first child, the queen’s hair began to fall out, making it difficult to sustain the height of pouf hairstyles.Footnote 30 Her hairdresser, Léonard, invented the coiffure à l’enfant instead: a more rounded and ‘natural’ style using shorter hair, which was quickly emulated by ladies at court. Less hair meant less space for extravagant floral displays. Flowers were now relegated to bonnets and hats, as demonstrated in the c. 1782 portrait of Madame Élisabeth by Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun, Madame Élisabeth, oil on canvas, c. 1782, 110 × 82 cm. Châteaux de Versailles et des Trianons, Versailles, MV 8143. © GrandPalaisRmn (Château de Versailles) / Gérard Blot.

Changing fashions for clothing had a similar impact on the sales of artificial flowers in the 1780s. As the royal family expanded, Marie-Antoinette adopted a looser and lighter style of dress, recommended by authors such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau for the health of mother and child. The chemise à la reine was the forerunner of neoclassical styles that became widespread in the 1790s. While flowers could still be worn with this style of dress, and indeed were carried by Marie-Antoinette in her infamous portrait by Vigée Le Brun of 1783 (Figure 7), the draped fabrics offered fewer places to tuck or pin artificial flowers, unlike the heavily structured shape of the grand habit shown in Figure 3. Nevertheless, as gauzy drapery became assimilated into more familiar styles such as the robe à l’anglaise, flowers adorned the edges and seams of skirts, and bouquets were pinned to fichu scarves (Figure 8).

Figure 7. After Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun, Marie-Antoinette, oil on canvas, after 1783, 93 × 73 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 1960.6.41. Open access, public domain.

Figure 8. A. B. Duhamel, after Defraine, The first fashion magazine: magasin des modes nouvelles françaises et anglaises, 3e année, 2e cahier (Paris, 30 Nov. 1787), pl. 1, 21 × 35 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, RP-P-2009-1283. Open access, public domain.

Age might have been another factor in the evolution of Marie-Antoinette’s style during the 1780s, which impacted court fashion more widely. Her lady-in-waiting Madame Campan recalled that the queen worried about whether she was too old to wear flowers past her twenty-fifth birthday (which fell in November 1780); five years later, she reportedly warned Bertin that she would no longer wear flowers once she turned thirty.Footnote 31 Many fashion commentators in this period agreed that flowers were only appropriate for young women and should not be worn past the early thirties.Footnote 32 Perhaps the queen’s reluctance to wear flowers as she aged contributed to the relative stagnancy of Bertin’s flower sales between 1784 and 1790. Although Marie-Antoinette’s accounts from this period are not found in the dataset, the repercussions of her style choices extended far beyond her own wardrobe. With no royal mistress to rival the queen’s position at court, Marie-Antoinette became the focus of sartorial attention in Versailles and Paris. Indeed, copies of the gowns that Bertin designed for the queen were available to buy in her Paris store eight days after Marie-Antoinette had worn them in public.Footnote 33 The connections presented here between events in the queen’s personal life, her changing style as a result, and trends of flower purchases in Bertin’s accounts confirm the importance of Marie-Antoinette’s impact on elite fashion in this period.

Despite the queen’s declining interest in floral accessories during the 1780s, a continued vogue for pastoralism – as demonstrated in Figures 6–8 and discussed in detail below – ensured that flowers did not disappear from fashion altogether. Indeed, Table 1 shows that 1780 and 1782 were boom years for Bertin’s sales of artificial flowers. While the princess Galitzin’s significant order of ninety-five flowers in 1780 helps to explain the sudden increase in that year, no such standout consumer exists for 1782, in which twenty-four purchasers bought 159 flowers between them. Many of the types of flowers purchased that year fitted a pastoral theme, such as hay roses, delphiniums, and cornflowers. The figures also show that almost a third of the year’s flowers were bought in January, with a particularly strong showing of hyacinths. On 21 January 1782, Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette held a celebration for the new dauphin, who had survived the dangerous first three months of his life and remained in good health (Figure 9). Hyacinths would have been an appropriate choice of flower to wear to the celebration, since they are one of the first flowers to bloom after winter, suggesting new life and hope. The court festivities in early 1782 seem to have contributed to an especially successful year in artificial flower sales for Bertin.

Figure 9. This engraving shows the celebrations for the dauphin in January 1782. Garlands of flowers decorate the chandeliers hanging from the ceiling and the sugar sculptures on the tables, and there is some impressionistic indication of flowers in the hair of women in the foreground. Jean-Michel Moreau, Le festin royal, engraving, 1782. Musée Carnavalet, Paris, G.175. Creative Commons licence.

Events in the scientific community may also have influenced the spike in flower purchases in 1782. That year, an Austrian physician, Balthasar Hacquet (1740–1815), discovered what he believed to be a new variety of pale yellow scabiosa flower growing in the Alps – Scabiosa trenta.Footnote 34 Although this plant was later proven to be part of a previously identified species, Hacquet’s claims sparked a rush among botanists to find more examples of the mysterious flower.Footnote 35 The search for the enigmatic plant within the pastoral idyll of the Alps might well explain a surge in popularity of the scabiosa flower in Bertin’s credit records. Only two different consumers had purchased the flower between 1772 and 1780, but five consumers ordered scabiosa flowers in 1782 alone, and two more followed suit in 1783. While the correlation is hard to prove definitively without further evidence, it is intriguing to note that botanical discoveries appeared to impact which flowers were worn in fashion. For some women, their clothing choices were closely entangled with scientific knowledge.

III

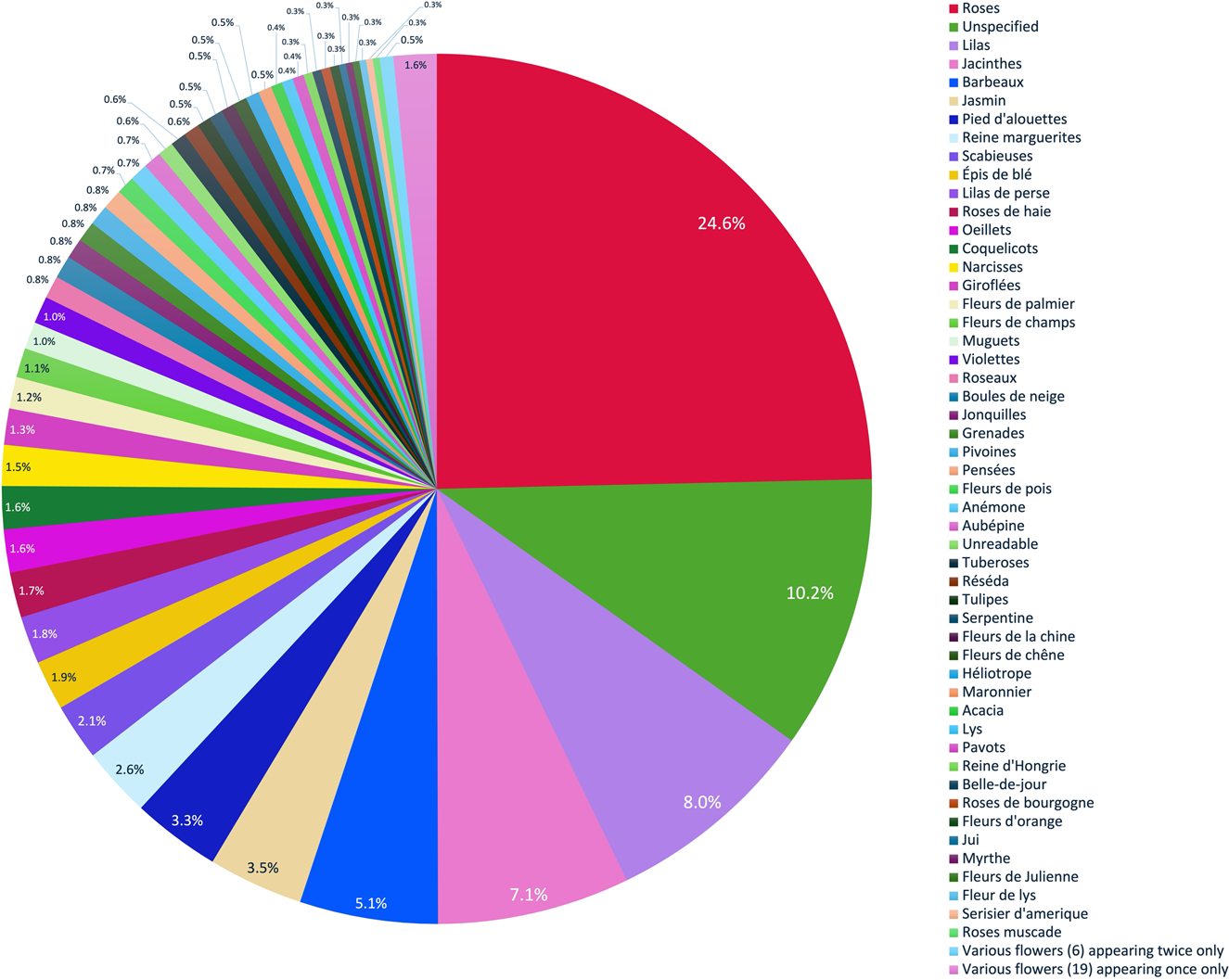

Bertin’s credit records contain a striking number of different flower varieties mentioned by their common French name (Figure 10). The dataset includes seventy-five different types of flowers, ranging from familiar garden varieties such as roses and hyacinths, to more unusual plants such as American cherry blossom (cerisier d’Amérique) and Indian jasmine (jui). The bills feature a high level of specificity. Bertin’s flower-makers were required to know how to make not only a silk rose, but also hay roses (roses de haie), pompom or Burgundy roses (roses de bourgogne), and musk roses (roses muscades). These distinctions suggest that the customer, the fashion merchant, and her flower-makers had sufficient botanical knowledge to differentiate types of flowers and make conscious decisions about which one would best suit their fashionable outfits.

Figure 10. Percentage of each flower type purchased, in Marie-Jeanne Bertin’s credit records, 1772–93.

A little over one tenth (10.2 per cent) of flower purchases did not specify the variety, but simply listed a bouquet or a garland of flowers. Many of these ‘unspecified’ flowers were described by colour, fabric, or an adjective such as ‘large’ or ‘assorted’, suggesting that the purchaser was not interested in the type of flowers so much as the overall aesthetic impact. In these instances, the flower type was probably decided by the fashion merchant according to the most suitable shape, colour, and size for the outfit for which it was intended. Some consumers switched between providing detailed descriptions of flowers and choosing not to specify the type, sometimes on the same day. In September 1789, for example, the duchesse de la Vauguyon ordered a variety of bouquets and garlands including a bouquet of colourful scabiosa, a bouquet of lilacs all in white, and a bouquet of clustered delphiniums in all colours, yet she seemed not to have minded which flowers went in an ‘assorted garland’ – the most expensive floral accessory of that day’s order.Footnote 36 The combination of precisely and imprecisely ordered flowers suggests that neglecting to specify the type did not necessarily correlate to a lack of botanical knowledge, but perhaps to a deference to the fashion merchant’s opinion.

Eleven consumers ordered only ‘unspecified’ flowers, and therefore probably did not know or mind which kinds of flowers they should buy. Interestingly, four of these eleven consumers were men. There are only twenty-six men present among the purchasers of flowers in the credit bills, meaning that a far higher proportion of men than women buying artificial flowers purchased ‘unspecified’ flowers only. Given that fashion merchants were only permitted by guild regulations to sell items for women’s dress, it is likely that these four men were purchasing on behalf of female relatives and might have been unwilling to specify what kind of flower for fear of making the wrong choice.Footnote 37 These results, while too small to hold great statistical significance beyond this study, lend strength to the idea that selecting flowers for dress was an intensely personal and meaningful process for women.

Of all the purchases that did specify the flower type, roses were by far the most common variety of flower. They accounted for 24.6 per cent of all flowers named in the bills, a figure that rises to 26.8 per cent when incorporating roses de haie, roses de Bourgogne, and roses muscades as well. An analysis of the number of consumers who bought roses reveals that 87.4 per cent of all customers who ordered flowers from Bertin requested roses at some point. Roses appear, therefore, to have been the standout choice for floral fashion.

The prevalence of roses is unsurprising given their deeply entrenched position in eighteenth-century French culture and the variety of meanings that they encapsulated. Roses have long been associated with both religious and secular love. They feature in Marian imagery (the ‘rose without thorns’), and in courtly romances from Le roman de la rose onwards.Footnote 38 Furthermore, while all types of flowers were used as analogies for female beauty and sexuality, the rose was the most prevalent metaphor. It combines an appealing shape, colour, and scent with a hint of danger from its thorns, thus becoming an apt representation of both the pleasure and the pain involved in love. The wide spectrum of symbolism attached to the rose ensured its place in the culture and the gardens of eighteenth-century France. By 1804, the naturalist Pierre-Joseph Buch’oz could confidently assert that the rose held ‘first place, without competition’ among ‘the flowers that adorn our gardens’.Footnote 39

Roses were also emblematic of women’s health and vitality. The flower was frequently used as an example of the most attractive colouring for a woman’s cheeks in treatises on health and beauty.Footnote 40 Indeed, a healthy blush was often created using powdered roses, which were common ingredients in cosmetic recipes.Footnote 41 Texts listing the medicinal properties of plants in eighteenth-century France suggested the rose for calming inflammation, soothing chest pains, and reducing hysteria.Footnote 42 Although the roses sold by Bertin were artificial, it is likely that both the manufacturers and the wearers of faux flowers added scent.Footnote 43 Reports suggest that the marquise de Pompadour enjoyed dropping perfume into her porcelain flowers, which she displayed in vases alongside real flowers to heighten the multi-sensory illusion.Footnote 44 Wearing a silk rose with the same smell, colour, and shape as a real flower might therefore have possessed some of its beneficial attributes, as well as engaging playfully with the viewer in a game of visual and olfactory deception.

The next most common flower types ordered were lilacs (lilas), hyacinths (jacinthes), cornflowers (barbeaux), and jasmine (jasmin). Lilacs, hyacinths, and jasmine were popular cultivated flowers in eighteenth-century gardens, with lilacs and jasmine especially valued for their scent. However, in the literature aimed at amateur female botanists, women were advised not to attempt growing ‘luxuriants’ such as hyacinths, because over-refinement had made them susceptible to disease and therefore tricky to grow successfully.Footnote 45 It is unclear whether female amateur gardeners followed this advice or not. The difficulty of growing luxuriant plants might have contributed to their popularity as artificial flowers, however.

The presence of cornflowers among the most popular types indicates the prevalence of wildflowers in this dataset. Other wildflowers commonly ordered from Bertin included daisies, ears of wheat, poppies, and flowers described by the umbrella term fleurs de champs (‘field flowers’). The portraits of Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun from the early 1780s give an indication of how these might have been worn on the brims of straw hats (see Figure 6), and indeed many of the wildflowers in Bertin’s credit bills were sold attached to hats (chapeaux) or poufs.

The trend for wearing wildflowers was influenced by pastoralism, which swept through French art, literature, and dress from the 1750s onwards, reaching its apex in the early 1780s, when Marie-Antoinette created her retreat at the Petit Trianon to live in a simpler, more rural style with her children and close friends. Pastoralism was often set in opposition to following fashion. Rousseau, an ardent proponent of pastoralism, wrote in Émile (1762) that a ‘love of fashion’ was ‘bad taste’ in women. Instead, he suggested, ‘Give to a young girl who has taste and despises fashion, some ribbons, some gauze, some muslin and some flowers; without diamonds, without pompoms, without lace, she will make herself an outfit that makes her a hundred times more charming.’Footnote 46 However, the popularity of Rousseau’s writing meant that his rejection of formal court fashion became – quite ironically – fashionable.

In Rousseau’s ideal world, which he had outlined in his 1761 novel Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse, genteel people would live entirely cut off from the unpleasant world of commerce, meeting all their simple needs in a self-sufficient manner with produce grown on their land.Footnote 47 The Rousseauian vision implies that women wearing flowers might have wandered through a field and nonchalantly plucked the blooms to lend their outfits a naïve charm. This sentiment is expressed visually in Vigée Le Brun’s stylized portraits of Marie-Antoinette’s Trianon circle, in which wildflowers are tucked carelessly into the ribbon of a straw hat. Women may indeed have adorned their clothes with real wildflowers, which are often easily preserved as dried flowers. However, the popularity of artificial wildflowers in Bertin’s credit bills suggest that many aristocratic women in Versailles and Paris, as well as on their country estates, created this apparently simple and natural style with the help of fashion merchants’ artifice.

By selling artificial flowers, especially wildflowers, fashion merchants could respond to the criticisms of fashion by authors such as Rousseau. As Jennifer Jones has argued persuasively, the fashion press played an instrumental role in ‘repackaging’ Rousseau’s arguments in order to reconcile pastoral simplicity with the luxury fashion market. Editors of fashion magazines pruned ‘away those aspects of Rousseau’s thought on women and consumption that would have threatened the luxury and fashion trades of Paris’, leaving only his commentary on the virtues of simple and natural adornment.Footnote 48 This study demonstrates that the repackaging of Rousseau occurred not only in the fashion press but also in the shops of fashion merchants such as Bertin. Flowers were one of the only accessories deemed suitable by Rousseau for women’s dress. By emphasizing artificial flowers within their business, fashion merchants could adapt to the spirit of the age which demanded simplicity and naturalism, while still maintaining their livelihoods. Seen in this light, flowers in fashion emerge as a reflection of the age’s obsession with pastoralism, as well as a trend actively promoted by fashion merchants as an effective business strategy.

Adopting a pastoral style of dress which incorporated flowers could also be advantageous for elite female consumers. Meredith Martin argues in her study of pastoralism in art and architecture that the apparent simplicity and naturalism of pastoral styles enabled elite women ‘to address the multiple, conflicting burdens of their gender and social station: as both guardians of nature and consumers of culture’.Footnote 49 At a time when aristocratic women came under frequent attack for their apparent artifice and lack of connection with ‘natural’ feminine behaviour, the integration of nature into fashion was a symbolic deflection of such arguments. Furthermore, by adopting the apparent simplicity of pastoral fashion, women presented a visual connection with nature while at the same time supporting the luxury goods industry – which even detractors of the fashion market had to admit was crucial to the nation’s economic success.Footnote 50 This social and cultural context is key to understanding the popularity of artificial flowers in the late eighteenth century.

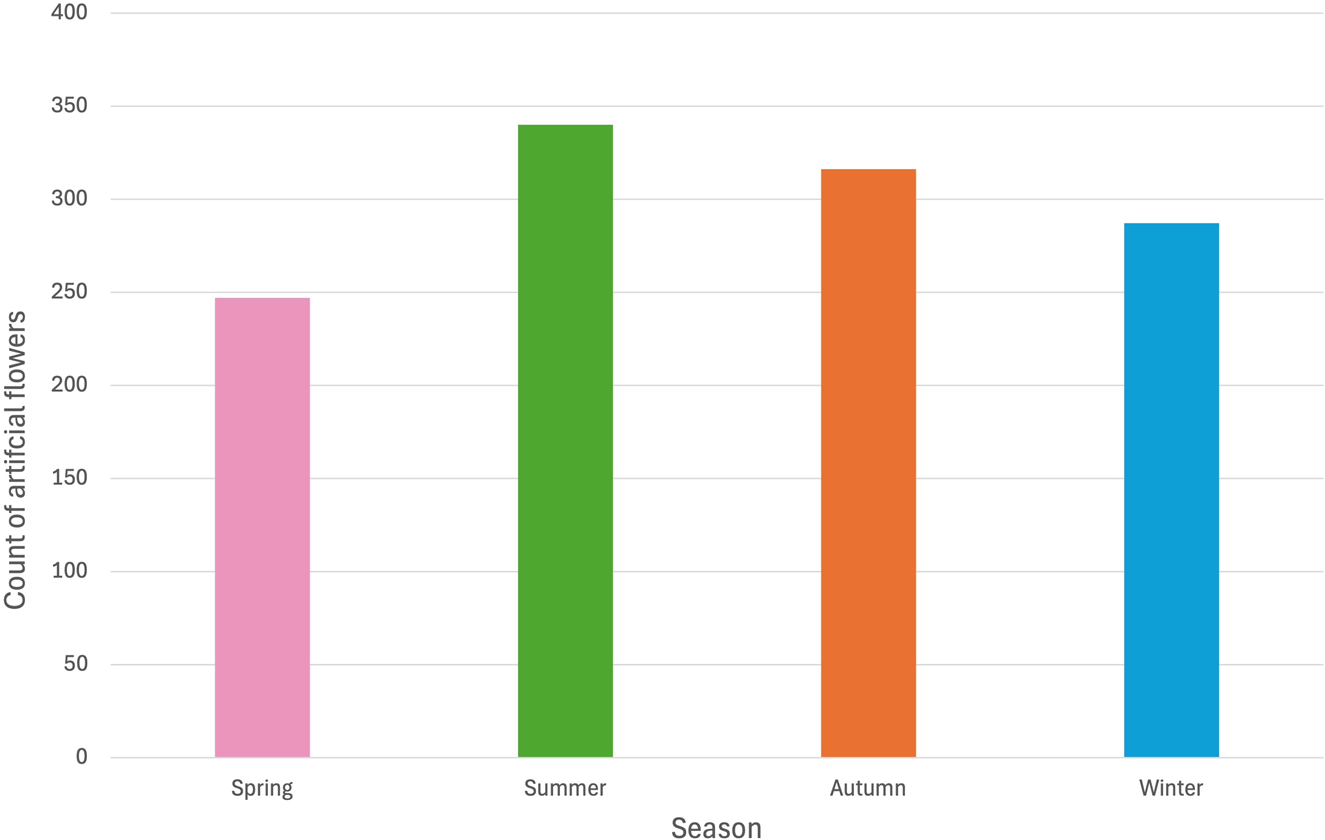

Another advantage of the artificial flower trade was that flowers could theoretically be produced in any season, without the limitations of nature imposed on the blooming of fresh flowers. The credit records indicate that artificial flowers were purchased all year round, with the numbers purchased in autumn and winter remaining comparable to those purchased in summer (Figure 11). The downturn in spring might be explained by the religious restrictions of Lent – a period of forty-six days falling between late February and early April (depending on the lunar calendar), during which time the purchase of new clothes and accessories was frowned upon.Footnote 51 It is also possible that artificial flowers in fashion were supplemented by real flowers during spring and summer, when most plants come into bloom. A month-by-month breakdown reveals that the two most popular months for purchasing flowers were January (139 flowers purchased) and July (144). As the accounts studied here only reflect purchases made on credit and never fulfilled, it is possible that customers wielded greater credit purchasing power at the beginning and middle of each year, since most accounting followed six-monthly schedules.Footnote 52 However, the small size of the dataset means that these explanations must remain tentative hypotheses, which can only be confirmed with further statistical analysis of other account books.

Figure 11. Artificial flowers purchased per season, in Marie-Jeanne Bertin’s credit records, 1772–93.

In 1805, Helmina von Chézy – a German writer visiting the court of Empress Joséphine – observed that ‘it is fashionable here always to adorn oneself with the flowers of the season (except in winter, when they like to wear imagined flowers)’.Footnote 53 She was not describing real flowers but artificial ones, since ‘natural flowers, however beautiful they may be, and however dear they are sold, are always too cheap to be worn or to adorn one’s hair’.Footnote 54 Chézy’s observation offers an intriguing glimpse into the comparative value of artificial flowers, created through the skilled labour of artisans, compared to real flowers which were considered ‘cheap’. Although Chézy was writing some years after the period studied here, Bertin’s credit records suggest that flowers were also generally worn according to season at the court of Marie-Antoinette, except in winter. Early spring flowers such as hyacinths, daffodils, and narcissus occurred most often in late winter and early spring, while the highest proportion of summer flowers such as jasmine, cornflowers, daisies, poppies, and pinks were purchased in the summer months. In winter, when few flowers are naturally in bloom, sales of the most popular flowers such as roses, lilacs, and jasmine remained consistently high.

A detailed inspection of the accounts shows that, while purchases of flowers often adhered to seasonality, consumers were not averse to mixing flowers from different seasons in the same outfit. A bouquet sold to the comtesse de Chabanner in November 1782 contained roses, jasmine, lilacs, and hyacinths, despite the fact that these flowers do not all bloom at the same time – and tend not to bloom naturally in November. Hyacinths and roses were an especially popular combination of flowers all year round. Just as seventeenth-century Dutch artists used creative licence to combine the most beautiful flowers of every season in their paintings, Bertin and her customers mixed flowers on garments in conscious acknowledgement of their artificiality, and the creative possibilities that artificial flowers afforded.

IV

Many of the popular flowers sold by Bertin would have been a familiar sight to her customers in the gardens and fields surrounding Paris during spring and summer. However, some flowers were more unusual, and might only have been found in a greenhouse. In purchasing exotic flowers, consumers made claims (both implicit and explicit) about their knowledge of foreign flora, their sophisticated taste, their individuality, and the skills of their fashion merchant and her flower-maker. Adorning a gown with roses might be aesthetically pleasing, but it was hardly unexpected, as the predominance of rose purchases in this study demonstrates. A more unusual flower choice ensured that the wearer was likely to stand out in a crowded salon or ballroom. Her clothing might prompt a conversation in which she could elegantly reveal her knowledge. Here, too, clothing might have functioned in similar ways to Dutch still-life paintings or cabinets of curiosities, with material goods helping to shape elite behaviour and conversation. Unlike many traditional means of displaying knowledge through objects, however, flowers in fashion were acutely associated with femininity.

Just as Sarah Easterby-Smith has argued that floral embroidery and botanical illustration were means through which women could display ‘intellectual engagement’ in a way ‘consistent with contemporary notions of female propriety’, wearing flowers did not obviously impinge on the traditionally ‘masculine’ realms of botanical classification, dissection, propagation, and theoretical study.Footnote 55 Nevertheless, the women who wore artificial flowers and the (predominantly female) artisans who made them used many similar skills and drew on knowledge associated with scientific botany. Consumers had to recall the names and properties of a particular flower to decide how it might best suit their outfit. Flower-makers would have to know each specimen intimately, counting petals and stamens, and recalling how its leaves were shaped and how each inflorescence was arranged.

One particular exotic flower – the palm tree blossom – offers a revealing case study into the dissemination of fashion knowledge among aristocratic women at this time. There are fourteen examples of palm tree flowers (fleurs de palmier) in the credit bills. It is unclear exactly which type of palm is being referred to, but it is probably either Phoenix dactylifera or Chamaerops humilis, both of which were known in eighteenth-century Europe and which produce clusters of yellow or cream flowers.Footnote 56 Today, potted palm trees can be found growing outdoors in Paris in parks such as the Jardin de Luxembourg, but they would have been far less common a sight in eighteenth-century Paris. The widespread planting of palm trees in northern Europe only occurred in the mid-nineteenth century, when botanists imported hardy species that could withstand the cold, and discovered that they could grow the trees from seeds rather than live specimens.Footnote 57 In fact, the botanist Matthias L’Obel had already discovered this fact in sixteenth-century Montpellier, but the knowledge seemingly did not take root outside that city, and palm trees were still relatively exotic in France at the time that Bertin was selling artificial flowers.Footnote 58

Purchases of palm flowers from the fashion merchant clustered around a particular time and a group of courtiers who probably knew each other well. The first mention of palm flowers in Bertin’s accounts comes from the orders of the comtesse de Ségur in January 1778, when she bought a branch of palm tree flowers in white satin. The comtesse (née Antoinette Élisabeth Marie d’Aguesseau) had married into a prominent military family at court in 1777 and was presumably in regular attendance at Versailles, as well as in the Parisian salons which her husband frequented. Two years later, in June 1780, another prominent courtier – Anne Thoynard de Jouy, comtesse d’Esparbès de Lussan (1739–1825) – ordered a large garland of palm tree flowers mounted on two levels, and a necklace made out of fine pleated lace with a garland of palm tree flowers underneath. The comtesse de Lussan (1739–1825) was a former mistress to Louis XV and a salonnière herself. She may have worn the palm tree flowers on the occasion of her niece’s wedding to the vicomte de Polastron and her subsequent court presentation that same month.

The next purchase of palm flowers in the accounts come from that same niece, the new vicomtesse de Polastron, exactly one month after her aunt, on 10 July. The vicomtesse ordered a robe à l’anglaise with garlands of pink palm flowers along the edge of the skirt and large garlands along the length of the drapery. Her dress was accompanied by a white straw hat with garlands of pink palm flowers, and two necklaces to match. The familial relationship between these two women suggests that one purchase of palm flowers might have inspired the other.

The wedding between the Esparbès de Lussan and Polastron families was a significant court event, and the bride and her relatives were probably the focus of sartorial attention during this period. It is surely no coincidence that, scarcely two weeks later, the Russian princess Nathalie Galitzin (1741–1837) ordered a similar white straw hat bordered by garlands of white and blue palm flowers. The princess ordered another hat with pink palm flowers in October of that year. It is unclear whether she was in France at the time, but a letter written on the occasion of Marie-Antoinette’s death reveals that she had visited the French court and had ‘infinitely precious memories’ of the queen.Footnote 59 A note from an order on 10 October 1780 suggests that she was then in England, which makes it possible either that she visited the French court earlier that year and saw the palm flowers in person, or that she received a report of them from across the Channel.Footnote 60

The connections between these women, who moved in the same social, geographical, and familial circles at various points in their lives, reveals the personal relationships which helped disseminate fashion information. The opinion of the theorist Gabriel Tarde that fashions are spread through imitation motivated by desire is entirely plausible in this scenario, since it is likely that the four women who purchased palm flowers between 1778 and 1780 saw the unusual floral accessory, admired it, and requested an imitation from their fashion merchant.Footnote 61 The appearance of the comtesse de Lussan and her niece the vicomtesse de Polastron wearing the same flower in quick succession might have signified a further emotional bond between the two women. Perhaps their purchases stemmed from conversations about fashion in which they discussed the latest novel accessory that they had found. As recent scholarship such as Dyer et al.’s Disseminating dress has shown, fashion was the subject of constant scrutiny in the press, in private letters, and in the printed image during this period.Footnote 62 Following the palm tree flower through the accounts of Bertin’s customers hints at dissemination of fashion through personal relationships and conversations which have left no further trace on the archival record, but which were nonetheless crucial means by which fashions spread.

It is worth noting the colours of the palm blossom in pink and blue, ordered by the vicomtesse de Polsatron and the princess Galitzin. These are unusual, if not impossible, colours for a palm tree flower grown naturally. The colour choice might indicate that neither woman had seen palm blossom in real life but had drawn inspiration instead from illustrations or descriptions.Footnote 63 Equally, the fact that artificial flowers can be dyed any colour means that the vicomtesse de Polastron and princess Galitzen might have requested brightly coloured flowers for the sake of novelty – especially when the palm blossom had recently appeared adorning the garments of prominent courtiers. Thus, while the purchases of palm tree flowers suggest a shared bond between these women, the choice of colour also serves to differentiate their individual tastes.

Perhaps the most unusual plant name mentioned in the accounts is jui. The plant itself is a familiar one: it is jasmine, the fifth most popular flower in the accounts, which became fashionable during the seventeenth century as an exotic import whose perfume was used to designate particularly pleasurable spaces (such as gardens and bedrooms).Footnote 64 However, the term jui comes from Indian languages.Footnote 65 While French colonial involvement with India had dramatically reduced after territorial losses in the Seven Years’ War, France maintained a presence on the Indian subcontinent, with five key trading posts along the coast.Footnote 66 It is possible that elements of Indian language were therefore in circulation in France at this time, alongside material goods and botanic specimens. The order for jui can be found in the vicomtesse de Polastron’s accounts from July 1780, when she commissioned the adornment of a grand habit or court dress in black taffeta with garlands of leaves and black jui flowers. The colour choice was presumably invented to match the fabric of the vicomtesse’s gown. Black jui might also refer to a Southeast Asian plant known as night-blooming jasmine (Nyctanthes arbor-tristis), which despite its common name is no longer classed as a true jasmine, and whose scented white petals occasionally turn black after falling to the ground.Footnote 67

At the time of ordering jui flowers, the vicomtesse was a few months shy of her sixteenth birthday and had just married the vicomte, becoming part of one of the most powerful families at the French court. She appears to have had a taste for flowers: she ordered twenty-one different types from Bertin between 1780 and 1786. The vicomtesse often made unusual choices in her orders, including the jui and palm tree flowers previously mentioned, as well as oleander flowers, the fragrant mignonette (réséda), and Persian lilac (lilas de perse). It is unclear why she ordered jasmine by its Indian name in 1780 and by its French name elsewhere in the bills. She seems to have been fond of jasmine flowers, as she chose them for her court presentation outfit in December 1780, ordering a necklace of jasmin d’Espagne and a matching bouquet de côté, which was presumably intended to be carried on the side or pinned to the side of her bodice (as seen in Figure 2). Perhaps the vicomtesse was inspired by a particular illustration or description of jui, or perhaps the name differentiated between the jasmine grown in Europe and the Southeast Asian night-blooming jasmine.

Many of Bertin’s elite customers would have had access to expensive botanical books, magazines, and often gardens of their own. It is less clear how the artificial flower-makers who worked for her would have obtained their knowledge. Customers might have brought cuttings, books, or illustrations with them to the shop. Alternatively, the fashion merchant and her flower-makers might have sought out plants in the surrounding area in Paris. Bertin’s shop, Au Grand Mogol, located at 149 rue Saint-Honoré from 1773 until 1789 (when she moved the short distance to 26 rue de Richelieu), was a few minutes’ walk away from the public gardens of the Palais Royal and the Tuileries. In the correct season, flower-makers could find some of the more common flower varieties growing in these gardens. For more unusual species, the well-known plant sellers Andrieux et Vilmorin could be found ten minutes’ walk east of the shop.Footnote 68 Their catalogues contain most of the plants listed in Bertin’s credit files, including some (though not all) of the more unusual ones.Footnote 69

V

This article has argued that the presence of artificial flowers in the credit records of Marie-Jeanne Bertin reveals close entanglements between botany and fashion in eighteenth-century France. The decades covered by Bertin’s career represent a unique moment, after French artisans had developed the skills to create naturalistic flowers, and before the advent of mass industrialization which distanced the consumer from the means and modes of production. The article has demonstrated that, in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, the purchase of floral accessories involved meaningful, conscious, and informed decisions. These decisions were probably underpinned by conversations about the aesthetics, the symbolism, and the botanical features of each artificial flower. The choice of floral accessories was undoubtedly affected by events at court, such as the death of Marie-Antoinette’s mother and the birth of the dauphin, as well as scientific discoveries such as the hypothesized Scabiosa trenta. Crucially, personal relationships and tastes also played an important role in women’s floral clothing purchases. The case of the palm tree blossom demonstrates how fashion inspiration circulated among communities – with unusual colours used to create novelty.

Historians seeking to establish the extent to which women engaged with scientific knowledge have often faced the problems typical to tracing women’s lives in the archives. Women were excluded from most formal institutions and academies; life events such as marriage and childbirth often led to women’s disappearance from or obfuscation in the record; and women’s writings are under-represented in published literature.Footnote 70 Approaching this methodological problem from the perspective of fashion enables insights into how elite female consumers and female artisans engaged on an embodied, practical, and material level with botany. Indeed, the findings presented here suggest that the artificial flower trade facilitated botanical knowledge exchange: between customer and fashion merchant during the purchase of clothing; between fashion-conscious women, who looked to each other’s outfits to inspire their purchase of unusual flowers; and among artificial flower-makers who may well have used the botanical resources of Paris to produce new designs for fashion merchants. In acknowledging the important role played by botanical knowledge in fashion, this article adds to the growing body of literature arguing that cultures of Enlightenment spread beyond the republic of letters to affect society on a much broader level.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Ulinka Rublack and Professor Lesley Miller for their advice from the early stages of this article’s development. I am grateful to Dr Giskin Day and Dr Ana Howie for their constant willingness to talk through ideas and proofread my work. Thanks also to the peer reviewers for their encouraging, helpful feedback.

Funding statement

This work was completed with the assistance of a Wolfson Postgraduate Scholarship and travel grants from Jesus College, University of Cambridge.

Competing interests

The author declares none.