Article contents

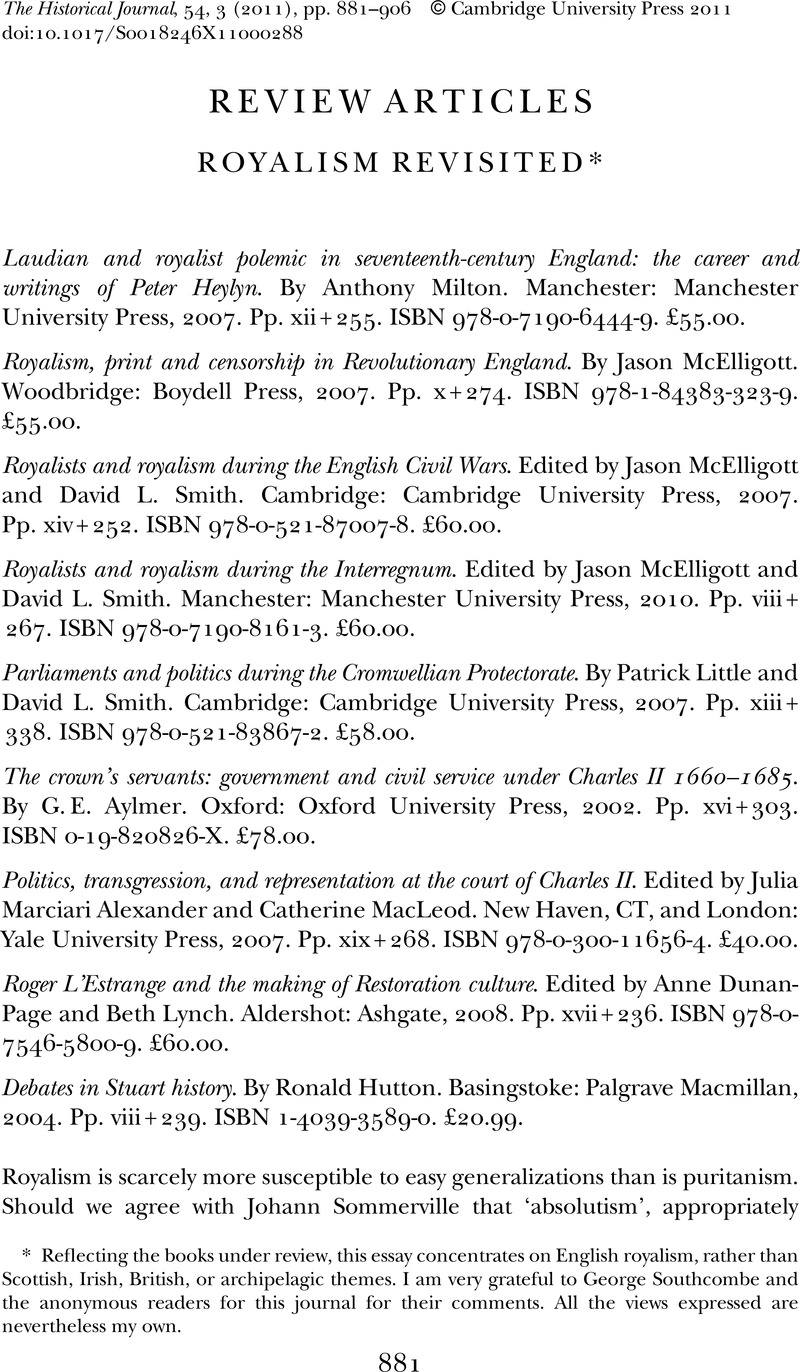

ROYALISM REVISITED*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 July 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Review Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 2011

References

1 Sommerville, J. P., Royalists and patriots: politics and ideology in England 1603–1640 (2nd edn, Harlow, 1999)Google Scholar, esp. ‘Revisionism revisited: a retrospect’; Daly, J. W., ‘Could Charles I be trusted? The royalist case, 1642–1646’, Journal of British Studies, 6 (1966), p. 43CrossRefGoogle Scholar. Cf. Burgess, Glenn, Absolute monarchy and the Stuart constitution (New Haven, CT, and London, 1996)Google Scholar.

2 Smith, David L., Constitutional royalism and the search for settlement, c. 1640–1649 (Cambridge, 1994)CrossRefGoogle Scholar, ch. 1, esp. pp. 9–11; Seaward, Paul, ‘Constitutional and unconstitutional royalism’, ante, 40 (1997), p. 227Google Scholar.

3 Aylmer, G. E., ‘Collective mentalities in mid-seventeenth-century England: II. Royalist attitudes’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 5th ser., 37 (1987), p. 29CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

4 Malcolm, Joyce Lee, Caesar's due: loyalty and King Charles, 1642–1646 (London, 1983)Google Scholar; Wood, Andy, ‘Beyond post-revisionism? The Civil War allegiances of the miners of the Derbyshire Peak Country’, ante, 40 (1997), pp. 23–40Google Scholar. See also Stoyle, Mark, Loyalty and locality: popular allegiance in Devon during the English Civil War (Exeter, 1994)Google Scholar.

5 Daly, J. W., ‘The origins and shaping of English royalist thought’, Historical Papers/Communications Historiques (1974), p. 15Google Scholar; Hinton, R. W. K., ‘Government and liberty under James I’, Cambridge Historical Journal, 11 (1953), p. 62CrossRefGoogle Scholar; idem, ‘Was Charles I a tyrant?’, Review of Politics, 18 (1956), pp. 69–87, esp. pp. 70–6CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

6 Daly, ‘Origins and shaping’, p. 25; Marston, Jerrilyn Green, ‘Gentry honour and royalism in early Stuart England’, Journal of British Studies, 13 (1973), pp. 21–43CrossRefGoogle Scholar. For a recent account, see Kane, Brendan, The politics and culture of honour in Britain and Ireland, 1541–1641 (Cambridge, 2009)Google Scholar.

7 Aylmer, ‘Royalist attitudes’, p. 30; Daly, James, ‘The implications of royalist politics, 1642–1646’, ante, 27 (1984), p. 755Google Scholar; Marston, ‘Gentry honour and royalism’, p. 23. See also Mendle, Michael, Dangerous positions: mixed government, the estates of the realm, and the making of the Answer to the xix propositions (Tuscaloosa, AL, 1985)Google Scholar.

8 Smith, David L., The Stuart parliaments, 1603–1689 (London, 1998)Google Scholar; Scott, Jonathan, Commonwealth principles: republican writing of the English Revolution (Cambridge, 2004)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Spurr, John, English puritanism, 1603–1689 (Basingstoke, 1998)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

9 Feiling, K. G., A history of the tory party, 1640–1714 (Oxford, 1924)Google Scholar; Scott, Jonathan, England's troubles: seventeenth-century English political instability in European context (Cambridge, 2000)CrossRefGoogle Scholar. For a telling specific incident from the 1670s, see Beddard, Robert, ‘Wren's mausoleum for Charles I and the cult of the royal martyr’, Architectural History, 27 (1984), pp. 36–45CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

10 Haigh, Christopher, English Reformations: religion, politics, and society under the Tudors (Oxford, 1993)Google Scholar.

11 Cf. de Groot, Jerome, Royalist identities (Basingstoke, 2004)CrossRefGoogle Scholar, where royalism is described as ‘a complex discourse of loyalty’ and ‘an amorphous collection of attitudes, complex and indistinct’ (pp. xv, 1).

12 For helpful considerations of this burgeoning theme in recent scholarship, see Raymond, Joad, ‘Describing popularity in early modern England’, Huntington Library Quarterly, 67 (2004), pp. 101–29CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Lake, Peter and Pincus, Steven, eds., The politics of the public sphere in early modern England (Manchester, 2007)Google Scholar; Cogswell, Thomas, Cust, Richard P., and Lake, Peter, eds., Politics, religion and popularity in early Stuart England: essays in honour of Conrad Russell (Cambridge, 2002)Google Scholar.

13 For the difficulty that many writers faced in trying to make sense of the Edwardian period, see MacCulloch, Diarmaid, Tudor church militant: Edward VI and the Protestant Reformation (London, 1999)Google Scholar.

14 For an early taster of a forthcoming major reconsideration of this theme, see Rose, Jacqueline, ‘Royal ecclesiastical supremacy and the Restoration church’, Historical Research, 80 (2007), pp. 324–45CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

15 For a later period, see Harris, Tim, ‘Tories and the rule of law in the reign of Charles II’, Seventeenth Century, 8 (1993), pp. 9–27Google Scholar.

16 The asperity of McElligott's comments is unfortunate bearing in mind the scale of Peacey's achievements, especially in the formidable Politicians and pamphleteers: propaganda during the English Civil Wars and Interregnum (Aldershot, 2004).

17 In what follows, the volume dealing with the Civil Wars will be labelled (i), and the interregnum (ii).

18 See his ‘Charles I: a case of mistaken identity’, Past and Present, 189 (2005), pp. 41–80CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and the ensuing ‘Debate’, with contributions by Clive Holmes, Julian Goodare, and Richard Cust, in Past and Present, 205 (2009), pp. 175–237Google Scholar.

19 Kishlansky thus offers a blunter variant of Sharpe, Kevin, The personal rule of Charles I (New Haven, CT, and London, 1992)Google Scholar.

20 For a recent demolition of Kelsey's core arguments which broadly restates traditional understandings of events in Nov. 1648 – Jan. 1649, see Holmes, Clive, ‘The trial and execution of Charles I’, ante, 53 (2010), pp. 289–316Google Scholar.

21 See also Worden, Blair, Literature and politics in Cromwellian England: John Milton, Andrew Marvell, Marchamont Nedham (Oxford, 2007)Google Scholar.

22 Smith, Geoffrey, The cavaliers in exile, 1642–1660 (Basingstoke, 2003)Google Scholar. See also his recent Royalist agents, conspirators and spies: their role in the British Civil Wars, 1640–1660 (Aldershot, 2011).

23 See now also Greenspan, Nicole, ‘Charles II, exile, and the problem of allegiance’, ante, 54 (2011), pp. 73–103Google Scholar.

24 Lacey, Andrew, The cult of King Charles the Martyr (Woodbridge, 2003)Google Scholar.

25 Pierce, Helen, Unseemly pictures: graphic satire and politics in early modern England (New Haven, CT, and London, 2008)Google Scholar. See also the excellent publicly accessible website: www.bpi1700.org.uk/index.html, accessed 24 Jan. 2011.

26 See also Sharpe, Kevin, Image wars: promoting kings and commonwealths in England, 1603–1660 (New Haven, CT, and London, 2010)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Knoppers, Laura Lunger, Constructing Cromwell: ceremony, portrait, and print, 1645–1661 (Cambridge, 2000)Google Scholar. Cf. Kelsey, Sean, Inventing a republic: the political culture of the English commonwealth, 1649–1653 (Manchester, 1997)Google Scholar.

27 Broadway, Jan, ‘No historie so meete’: gentry culture and the development of local history in Elizabethan and early Stuart England (Manchester, 2006)Google Scholar.

28 Publicly accessible at www.theclergydatabase.org.uk/index.html, accessed 24 Jan. 2011. See also Burns, Arthur R., Fincham, Kenneth, and Taylor, Stephen, ‘Reconstructing clerical careers: the experience of the Clergy of the Church of England Database’, Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 55 (2004), pp. 726–37CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

29 See also Smuts, R. Malcolm, Court culture and the origins of a royalist tradition in early Stuart England (Philadelphia, PA, 1987)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

30 See also David Scott, ‘Rethinking royalist politics, 1642–1649’, in John Adamson, ed., The English Civil War: conflict and contexts, 1640–1649 (Basingstoke, 2009), pp. 36–60; Paul Seaward, ‘Clarendon, Tacitism, and the civil wars of Europe’, in Paulina Kewes, ed., The uses of history in early modern England (San Marino, CA, 2006), pp. 285–306.

31 Cressy, David, Dangerous talk: scandalous, seditious, and treasonable speech in pre-modern England (Oxford, 2010)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

32 Hugh Trevor-Roper, ‘Oliver Cromwell and his parliaments’, in Richard Pares and A. J. P. Taylor, eds., Essays presented to Sir Lewis Namier (London, 1956), pp. 1–48; repr. in Religion, the reformation, and social change (London, 1967).

33 Little, Patrick, Lord Broghill and the Cromwellian union with Ireland and Scotland (Woodbridge, 2004)Google Scholar.

34 See also Jason Peacey's essays in Little, Patrick, ed., The Cromwellian Protectorate (Woodbridge, 2007)CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and idem, ed., Oliver Cromwell: new perspectives (Basingstoke, 2009).

35 For a very different – and extremely convincing – picture, see now Fitzgibbons, Jonathan, ‘“Not in any doubtfull dispute”? Reassessing the nomination of Richard Cromwell’, Historical Research, 83 (2010), pp. 281–300CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

36 Rutt, J. T., ed., The diary of Thomas Burton (4 vols., London, 1828)Google Scholar, i, p. 240.

37 The king's servants: the civil service of Charles I, 1625–42 (London, 1961); The state's servants: the civil service of the English Republic, 1649–60 (London, 1973).

38 For some bracing recent comments on this trend, see Davies, C. S. L., ‘Representation, repute, reality’, English Historical Review, 124 (2009), pp. 1432–47CrossRefGoogle Scholar. (Aylmer does offer brief comments on ‘symbols and emblems of state’: pp. 243–9).

39 See the catalogue, Painted ladies: women at the court of Charles II (New Haven, CT, and London, 2001).

40 See also Jenkinson, Matthew, Culture and politics at the court of Charles II, 1660–1685 (Woodbridge, 2010)Google Scholar.

41 Sharpe, Kevin, Selling the Tudor monarchy: authority and image in sixteenth-century England (New Haven, CT, and London, 2009)Google Scholar; idem, Image wars.

42 For a summary account, see his ‘Politics and theatrical culture in Restoration England’, History Compass, 5 (2007), pp. 1500–20CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

43 Esp. Sonya Wynne, ‘The mistresses of Charles II and Restoration court politics’, in Eveline Cruickshanks, ed., The Stuart courts (Stroud, 2000), pp. 171–90.

44 For an earlier period, see Patrick Collinson, ‘Ecclesiastical vitriol: religious satire in the 1590s and the invention of puritanism’, in John Guy, ed., The reign of Elizabeth I: court and culture in the last decade (Cambridge, 1995), pp. 150–70. (I am grateful to George Southcombe for reminding me of this comparison.)

45 Harris, Tim, Revolution: the great crisis of the British monarchy, 1685–1720 (London, 2006)Google Scholar.

46 Consolidated in his ‘“The horrid popish plot”: Roger L'Estrange and the circulation of political discourse in late seventeenth-century London (Oxford, 2010).

47 Cf. Claire Walker, ‘“Remember Justice Godfrey”: the popish plot and the construction of panic in seventeenth-century media’, in David Lemmings and Claire Walker, eds., Moral panics, the media and the law in early modern England (Basingstoke, 2009), pp. 117–38.

48 See the excellent Oxford dictionary of national biography, entry by Harold Love.

49 Claydon, Tony, Europe and the making of England, 1660–1760 (Cambridge, 2007)Google Scholar. Such concerns also animated Peter Heylyn: see Milton, pp. 17–19, 22–4, 91–2, 156–7, 206, 210–13, 231–2.

50 See also Harold Love, ‘The look of news: popish plot narratives 1678–1680’, in John Barnard and D. F. McKenzie, eds., The Cambridge history of the book in Britain, iv:1557–1695, with the assistance of Maureen Bell (Cambridge, 2002), pp. 652–6.

51 Geoff Kemp, ‘L'Estrange and the publishing sphere’, in Jason McElligott, ed., Fear, exclusion and revolution: Roger Morrice and Britain in the 1680s (Aldershot, 2006), pp. 67–90. See also, idem, ‘Ideas of liberty of the press, 1640–1700’ (Ph.D thesis, Cambridge, 2001); idem and Jason McElligott, eds., Censorship and the press, 1580–1720 (4 vols., London, 2009).

52 For the increasingly politicized theme of ‘public engagement’, see the activities of the Institute for the Public Understanding of the Past, at the University of York, notably a recent conference on the 10th anniversary of Simon Schama's A History of Britain: www.york.ac.uk/ipup/events/schama/televisualizing-report.html, accessed 24 January 2011.

53 An earlier version appeared in Bentley, Michael, ed., Companion to historiography (London, 1998)Google Scholar.

54 This is not to deny the brilliance of Blair Worden's hugely influential essay, ‘Oliver Cromwell and the sin of Achan’, in D. E. D. Beales and G. F. A. Best, eds., History, society and the churches: essays in honour of Owen Chadwick (Cambridge, 1985), pp. 125–45.

55 Hutton, Ronald, Charles II: King of England, Scotland and Ireland (Oxford, 1989)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

56 Besides those works already mentioned, in the last twenty-five years see also Sharpe, Kevin, Criticism and compliment: the politics of literature in the England of Charles I (Cambridge, 1987)Google Scholar; Potter, Lois, Secret rites and secret writing: royalist literature, 1641–1660 (Cambridge, 1989)Google Scholar; Loxley, James, Royalism and poetry in the English Civil Wars: the drawn sword (Basingstoke, 1997)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Bevington, David and Holbrook, Peter, eds., The politics of the Stuart court masque (Cambridge, 1998)Google Scholar; Wilcher, Robert, The writing of royalism, 1628–1660 (Cambridge, 2000)Google Scholar; Angela McShane Jones, ‘Roaring royalists and ranting brewers: the politicization of drink and drunkenness in political broadside ballads from 1640 to 1689’, in Adam Smyth, ed., A pleasing sinne: drink and conviviality in seventeenth-century England (Woodbridge, 2004), pp. 69–87; McElligott, Jason, ‘The politics of sexual libel: royalist propaganda in the 1640s’, Huntington Library Quarterly, 67 (2004), pp. 75–99CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

57 Scott, Commonwealth principles; Mark Goldie, Roger Morrice and the puritan Whigs (Woodbridge, 2007); Tyacke, Nicholas, ed., England's long reformation, 1500–1800 (London, 1998)Google Scholar.

58 Gardiner, S. R., ed., The constitutional documents of the puritan revolution, 1625–1660 (3rd edn, Oxford, 1906), p. 385Google Scholar.

59 Compare Anthony Milton, ‘Anglicanism and royalism in the 1640s’, in Adamson, ed., English Civil War, pp. 61–81, and Burgess, Glenn, British political thought, 1500–1660: the politics of the post-reformation (Basingstoke, 2009), p. 205CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

60 Hirst, Derek, ‘Locating the 1650s in England's seventeenth century’, History, 81 (1996), pp. 359–83CrossRefGoogle Scholar; idem, ‘The failure of godly rule in the English republic’, Past and Present, 132 (1991), pp. 33–66CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

61 Gardiner, ed., Constitutional documents, pp. 416, 455. See the classic account by Worden, Blair, ‘Toleration and the Cromwellian Protectorate’, Studies in Church History, 21 (1984), pp. 199–233CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

62 Collins, Jeffrey, ‘The church settlement of Oliver Cromwell’, History, 87 (2002), p. 20CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

63 For a local example, see Clark, Richard, ‘Why was the re-establishment of the Church of England possible? Derbyshire: a provincial perspective’, Midland History, 8 (1983), pp. 86–105CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

64 For instance, Anthony Milton's major current Leverhulme-funded project, ‘England's second Reformation: the battle for the Church of England, 1636–1666’, and forthcoming publications by Fincham and Taylor. See also Judith D. Maltby, ‘Suffering and surviving: the civil wars, the Commonwealth and the formation of “Anglicanism”, 1642–1660’, in Christopher Durston and Judith D. Maltby, eds., Religion in revolutionary England (Manchester, 2006), pp. 158–80.

65 Tim Harris, ‘“A sainct in shewe, a Devill in deede”: moral panics and anti-puritanism in seventeenth-century England’, in Lemmings and Walker, eds., Moral panics, pp. 97–116.

66 Miller, John, ‘The potential for “absolutism” in later Stuart England’, History, 69 (1984), 187–207CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Hill, Christopher, The experience of defeat: Milton and some contemporaries (London, 1984)Google Scholar.

67 Maltby, Judith D., Prayer book and people in Elizabethan and early Stuart England (Cambridge, 1998)Google Scholar; Woodhouse, A. S. P., Puritanism and liberty: being the army debates from the Clarke manuscripts, with supplementary documents (London, 1938)Google Scholar; Coffey, John, ‘Puritanism and liberty revisited: the case for toleration in the English revolution’, ante, 41 (1998), pp. 961–85Google Scholar.

- 2

- Cited by